Most of us have been there at one point or another in our lives: adrift. To the extent that human existence can be divided into something like “chapters,” there are occasions where one ends before a new one begins, and these interregnums tend to turn up, by and large, after graduating from some learning institution or another, be it a high school, college, grad school, whatever. For Milo, the protagonist/authorial stand-in at the center of John Carvajal’s self-published 2020 graphic novel/memoir-in-all-but-name Sunshine State, it appears as though his time spent after exiting his likely-shitty Florida high school has been an extended “lost weekend” of sorts, all booze fog and pot haze and dead-end gigs and furtive stabs at piecing together something akin to a purpose for his time on this Earth.

Fortunately (or maybe not?), his entire small social clique is equally rudderless, so he’s hardly alone, but being of Colombian ancestry and origin puts him in the rather unique position of being doubly lost as both a kid without a plan and the proverbial stranger in a strange land, trying to hold on to identities both personal and cultural at a point in life where one’s options generally boil down to assimilating into the machinery of capitalism on some level, or slowly starving. The whole thing is, as the saying goes, a sticky wicket.

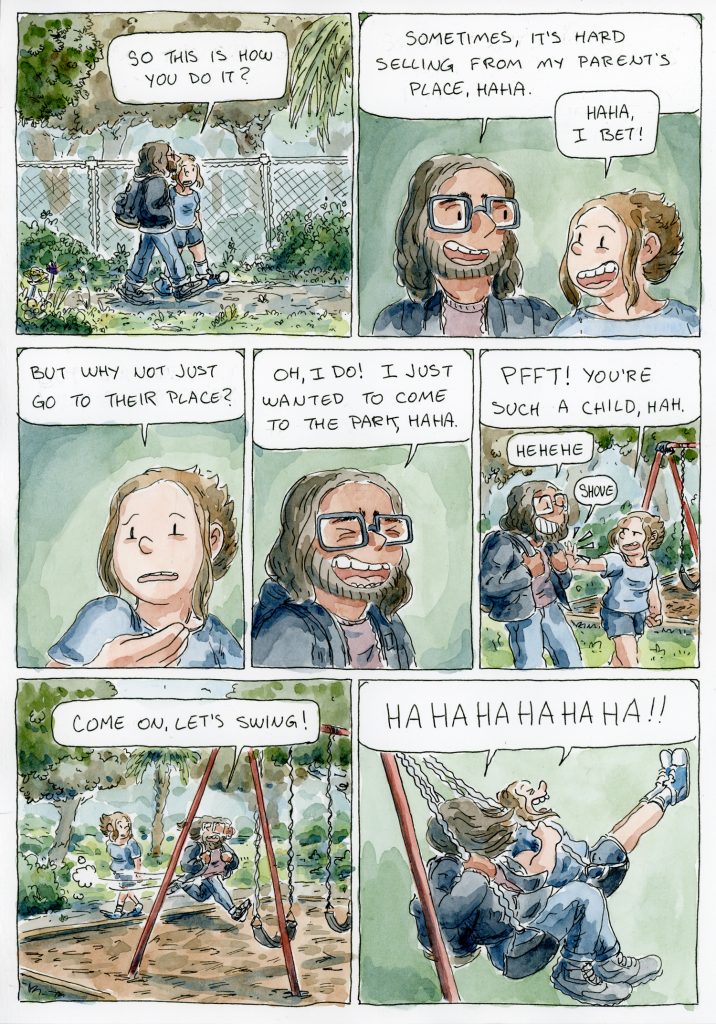

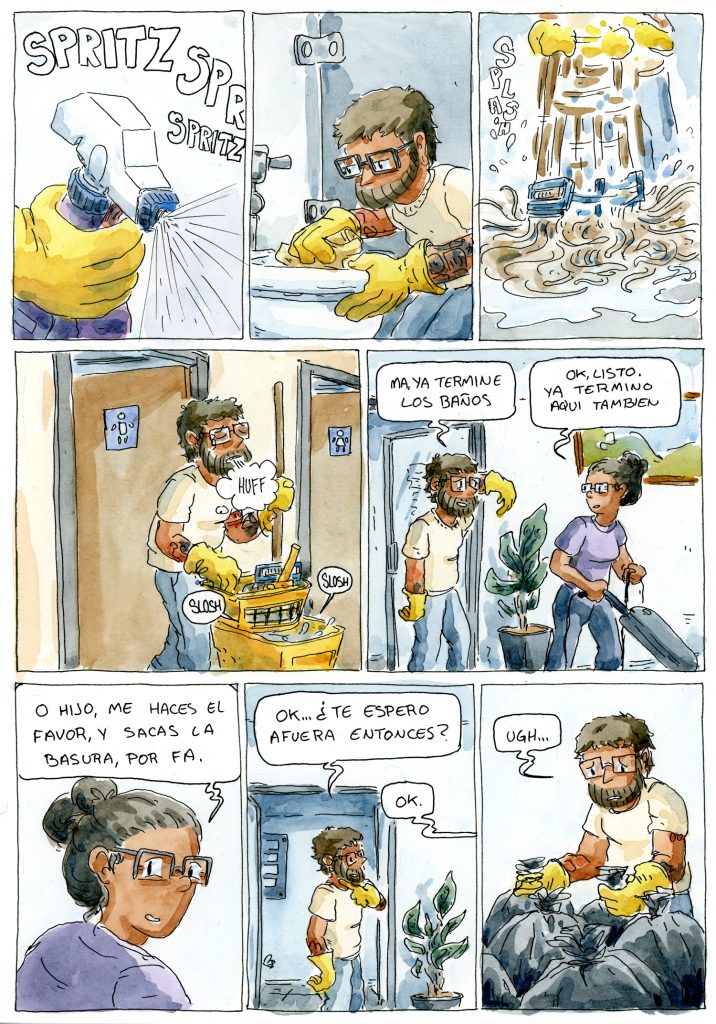

And so is getting through certain portions of this book if, like me, you don’t speak Spanish, but hey, I guess that’s what Google Translate is for, right? And besides, turnaround is both fair play and, in this particular case, decidedly effective as a narrative trope in that it puts readers in the same “fish out of water” position that Milo lives in pretty much 24/7. Fortunately, Cavajal’s got a real penchant for authentically-written dialogue, so going to the effort of translating certain segments, and even entire pages, doesn’t feel like “work” in the least because you actively won’t want to miss out on a single line that’s being spoken.

By extension, this dedication to authenticity informs every aspect of the work as a whole, and it’s a damn good thing that it does because, if we’re being brutally honest here, most of us who are into “indie,” or “alternative,” or whatever terms you want to use, comics have read a lot of stories like this over the years. The tug and pull between cultures adds a little something to Cavajal’s tale, there’s no doubt about that, but, apart from that, this is a book that — and I mean no offense by this, I’m simply calling it like it is — treads on some fairly familiar terrain. The only other major distinction on offer here being that this is a pre-art school thinly-veiled-memoir rather than yet another entry into the overflowing canon of post-art school thinly-veiled-memoirs. Don’t expect any reinvention of the wheel to be taking place before your newly-opened eyes, then, but I’d caution you not to be either too hasty or cynical — just because you’ve seen something done more times than you can count doesn’t mean that you can’t be reasonably enthralled by, and even find yourself invested in, yet another example of it, right? Granted, it does mean that the cartoonist who has created the work needs to do their job really well in order to both win you over and keep you on board, but hell, that’s true of any and all comics, regardless of genre.

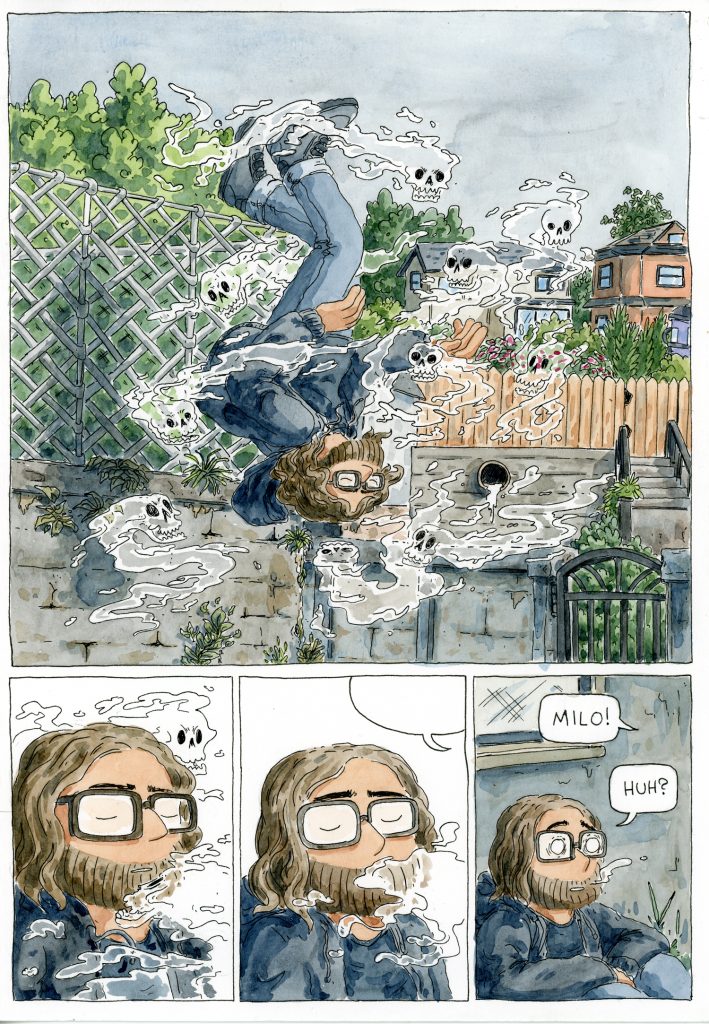

Fortunately, Carvajal acquits himself very nicely in that regard. Yes, nights out partying, days in wishing you hadn’t been out partying, girls you’re friends with that you want to be more than friends with, family pressure to do something with your life, jobs you could care less about, and friends who may not be the best influences but do tend to have access to the best drugs are all ubiquitous features in stories about young dudes trying to find their way (or maybe that should be trying to find their way toward finding their way with this one, because Milo has nothing if not a damn long way to go), but that’s largely because they’re ubiquitous features in the lives of young dudes trying to find their way (or maybe that should be — ahh, forget it). To the extent, then, that certain personality traits, pastimes, and attitudes of Milo’s (maybe especially his nihilism) are annoying, it’s only because, by and large, guys his age really are annoying in those particular ways and for those particular reasons, so again — points to Carvajal for authenticity, even when ditching it would, by default, add to his book’s likability factor.

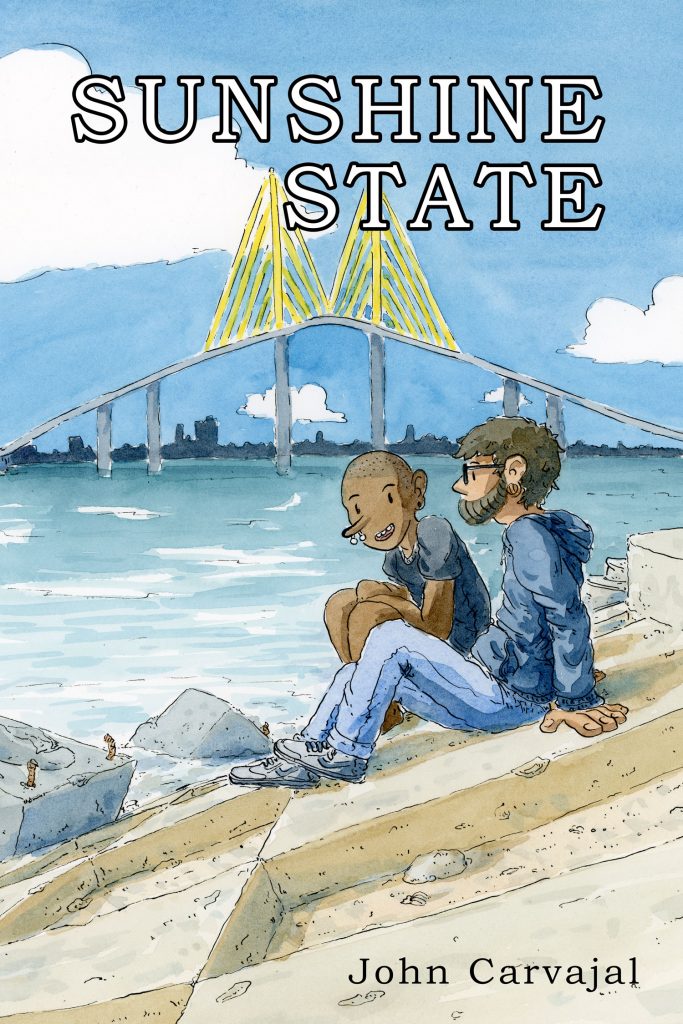

Which isn’t to say that Milo, his friends, and his family aren’t inherently likable for the most part — they are. And that inherent likability finds its strongest form of expression in Cavajal’s loose-lined, expressionistic, just-exaggerated-enough cartooning, complete with lush and vibrant Floridian hues and well-chosen digital (I’m assuming) watercolor effects. His people look flawed, sure, but so do you and me, and while his eminently relatable writing ensures that these are the kind of flawed people you want to read about, his polished-but-in-no-way-slick cartooning seals the deal by making sure they’re also the kind of people you want to look at.

As I sat down to write this review I was prepared to say that if I had one quibble with this work that might fairly be classified as a “consistent” one, it’s the extent to which Carvajal can sometimes lean too hard toward the overly-expository or reach to impose deep meaning upon situations that don’t necessarily call for it. There are, for instance, passages where people exhibit a greater degree of self-reflection and/or plain old wisdom than their characters would seem to be capable of. The more I thought about it, though, it occurred to me that hey — isn’t that how life sometimes works? I mean, who hasn’t been surprised on occasion by a friend or acquaintance spilling their guts at a weird time, or exhibiting a sudden philosophical streak out of nowhere only to lose it again later the same evening? There are times where it makes for clunky or awkward reading, but shoot — situations like that are usually pretty clunky and awkward in reality, as well.

It’s also very much — and very obviously — the case that Sunshine State is a story about an awkward time in the life of a guy whose default setting is awkward in the first place, and who doesn’t do himself any particular favors by trying his hand at low-level drug dealing and playing a bit too fast-and-loose with both his depression and anger management issues. As such, it’s fair to say that even its occasional flaws are easily overlooked as being thematically apropos in relation to its subject matter. It’s not perfect, but it is both honest and weirdly endearing. As somebody who spent some time trying to find their footing in life myself, I can’t say the book made me feel nostalgic for my “slacker” years, but it did help to remind me that they weren’t a total waste and that they were a necessary bridge between the person I was and the person I grew into. Or should that be the person I’m growing into still?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply