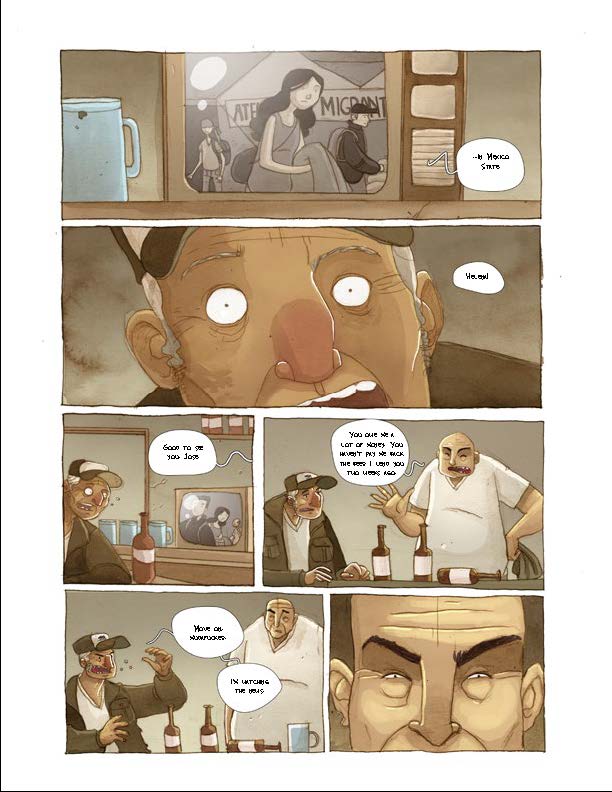

The kidnapped child has, as of recently, become a common storyline: a white middle-class family man is willing to go to any length to rescue his missing daughter from immigrants, foreigners, and psychopaths. But in Augusta Mora’s Illegal Cargo (Black Panel Press, 2020), José Sendero is not just another replication of Liam Neeson from Taken, and this story is not another self-righteously violent thriller that gets its kicks by appealing to its barely concealed xenophobia. José’s daughter Helena had gone missing in Mexico on her way from El Salvador to the United States. And the hero, José, is a neglectful and unmotivated alcoholic who did not think to wonder if she had arrived safely until informed otherwise by a stranger. Mora’s gut-wrenching graphic novel is a critique not so much of the American Dream, as of what poverty will do to people. In an impoverished country that stomps on any hopes of economic mobility, it is no surprise that José came to stop caring or that Helena came to believe that a potentially fatal journey might be worth taking.

But perhaps dangerous trips are sometimes worthy to be made, and it is only through José’s encounter with the Siguanaba, a beautiful female spirit with the face of a horse’s skull, that he finally decides to search for Helana. Mora reworks this figure of Central American folklore such that the Siguanaba becomes more than what it had been: a cautionary tale for men against taking sexual advantage of women, a slur synonymous with the “femme fatale”, or a disciplinary myth brought over by Spanish colonizers. Through haunting blue tones, thick and curling panel borders, and arresting diagonals, Mora’s Siguanaba seems to make her appearance straight from a fairy-tale. But she also acquires a decidedly political role in this story, lifting José from his rut of solitude and urging him to rescue Helena. One nevertheless wonders, by the story’s end, if the Siguanaba has led José to his doom after all. For when he is unable to find his daughter in the slums of Mexico, it is the Siguanaba whom he blames.

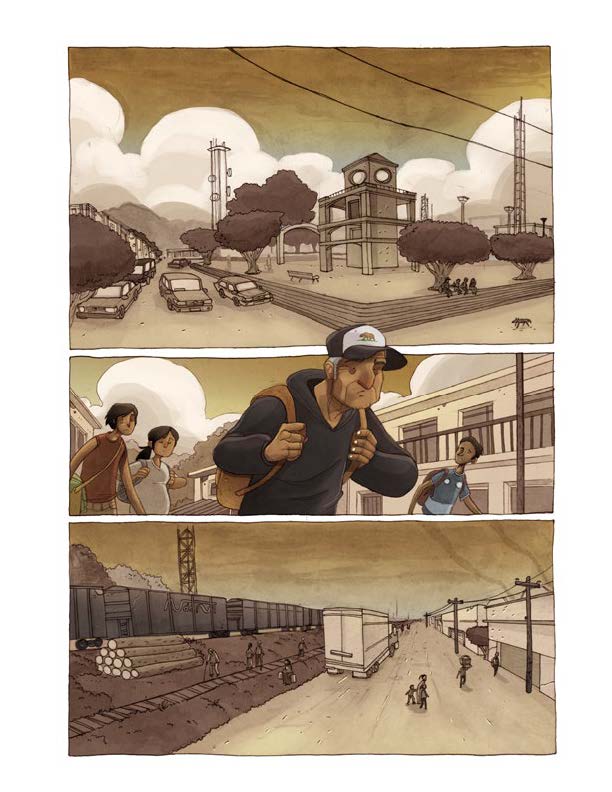

Given that it is the Siguanaba who leads José on this northward expedition, is Mora dismissing the journey of other migrants and asylum seekers? Sinister signs of the American Dream abound, from television images to whispers from urban hustlers and finally, even to the most identifying feature of José’s character design, the California flag’s bear on his cap. Although José is never reunited with Helena, his story transcends mere despair. Just as before his journey began, the Siguanaba had compelled him to re-examine the steps leading to his current plight, so too does her re-appearance remind him of the hellish journey he had undertaken. However, the Siguanaba had not led José into a dead end because he had already been living in one. For when José joins the larger movement of parents searching for their children who had gone missing in Mexico (based on Mora’s own involvement in the protest organized by the Caravan of Mothers of Missing Migrants), he finally takes charge of his life by realizing that the only way to make a meaningful difference is by contributing to something larger than his own goals. Gazing upon the imposing wall with photographs of missing children, José resolutely tells himself, “I have to accept it… I can’t do this alone… This is the only way.” The continuing sorrow and hardship of these parents are not idealized or mystified through the presence of the Siguanaba. Rather, she reveals the spiritual dimension which Jose’s task finally acquires through collective action. He realizes that neither his pain nor his task are unique ones. The collective approach does not magically resolve their seemingly impossible task, but rather makes the task feel bearable enough for each parent to continue their search without losing hope.

Responsible for these missing children are the numerous crime organizations that exploit the migrants who must pass through Mexico in order to reach the United States. By either ransoming or trafficking the people they have captured, these gangs have found a way to capitalize upon the structural inequalities between Latin America and the so-called Promised Land. Just as Roberto Bolaño has conveyed through his grotesque and spiraling thousand-page magnum opus 2666, in which there is no single cause or network responsible for its chains of murders and abductions, Mora’s moral universe likewise refutes any simplistic solution. Alongside José’s journey is a subplot that follows a crime ring and its own infighting. Although this seems to be José’s only lead to finding Helena, the reader nevertheless realizes that it is unlikely they are connected to her disappearance at all. Rather, we are pressured to understand these criminals on their own terms, independently of Jose’s quest. When the densely tattooed Dimas is about to execute a group of traitors, Dimas’ childhood memories of war suddenly manifest themselves through gristly monochromatic and wordless panels. The novel historicizes without attempting to justify his turn towards violent crime. This side narrative seems to tell us that although one can never fully understand evil, the refusal to try to understand where evil comes from is no different from the refusal to look evil in the face.

Even with its gorgeous landscapes, finely rendered linework, and many memorable faces, the most striking visual aspect of Illegal Cargo is the constantly shifting color palette. In one four-panel layout, distinctive colorways convey the passing of time and the changing of seasons, as José endures heat, rain, snow, and boredom on the notorious train known as La Bestia, or “The Beast.” Also called El tren de la muerte (“the train of death”) or El tren de los desconocidos (“the train of unknowns”), this nearly 1,500-mile-long train has been responsible for the injuries and deaths of unrecorded numbers of migrants each year. [1] As one character tells José, this is his fifth time riding La Bestia, and on his previous attempt, he had sacrificed his right arm and, ultimately, his boxing career. And towards the novel’s conclusion, this former boxer is senselessly murdered by Dimas’ gang.

Mora’s unflinching illustrations of migration seems to align him with the comics journalism of the likes of Joe Sacco and Sarah Glidden. But despite the peculiar narrative framing by the white documentary filmmaker who first informs José of his daughter’s disappearance, and who herself disappears from the story without explanation, Mora does not view himself as producing a kind of journalism. Rather, Mora contrasts the graphic novelist with the photojournalist: “Graphic narrative has elements that perhaps photography or documentary movies do not. With cartoons, one can ‘capture’ moments that escape the camera. You control the graphics and can communicate your emotions and ideas. The chiaroscuro, the size of the vignettes, the kinetic lines, the expressions of the characters, the plans—all this helps generate a certain impact on the reader.”[2] This anonymous filmmaker at the story’s beginning is not only marked off from the somber grays and browns of El Salvador by her vividly colorful fashion, but also marked off by her seeming unawareness of José’s encounter with the Siguanaba, telling us: “I never found out what made José leave in search of his daughter. He grabbed a map of Mexico, analyzed the train’s route, and left his house silently.” Just as Mora’s previous Spanish-language works like Grito de Victoria (La Cifra Editorial, 2017) incorporated an autobiographical presence, so too might this character be interpreted as his authorial proxy which admits to his own outsider status. But oppositely, she may represent the limits posed by film and documentary in understanding the personal journey of migrants such as José and Helena, thus setting the stage for the intervention of a graphic novel which must also be rigorously grounded on research and interviews. If Mora’s deft illustrations and enrapturing plotline transport the reader as if into a nightmare, we are also grimly reminded of the hundreds of thousands of migrants who daily endure such travails. Illegal Cargo, at first, appears to be about U.S. immigration policies, as the group of parents searching for their missing children chant, “Immigrants are not criminals,” and the back cover asserts, “No one is illegal.” As Mora’s first English-language work, the novel seems to rely on this framing in order to satisfy its American readership and their expectations of what a story about migration should be: about ourselves, even if only to condemn ourselves. But the novel is more accurately about the criminal networks profiteering from these migration channels, and the countless people who have gone missing in Mexico as a result. Just as American border policies are not the sole cause of Helena’s disappearance, neither would border reform lead to her rescue or that of other missing children. The Anglophone reader is misled in the same way Jose had been by the Siguanaba. Expecting a story about the reunion of father and daughter, who make their way together to the U.S., Mora gives us instead the bleak realism of crime, political activism, and resilient hope in Mexico.

[1] – For further reading, see Oscar Martinez’s widely acclaimed first-hand account, translated from Salvadorian, The Beast (Verso, 2013).

[2] – Interview with Augusto Mora, August 2019 – Latin American Literature Today

Leave a Reply