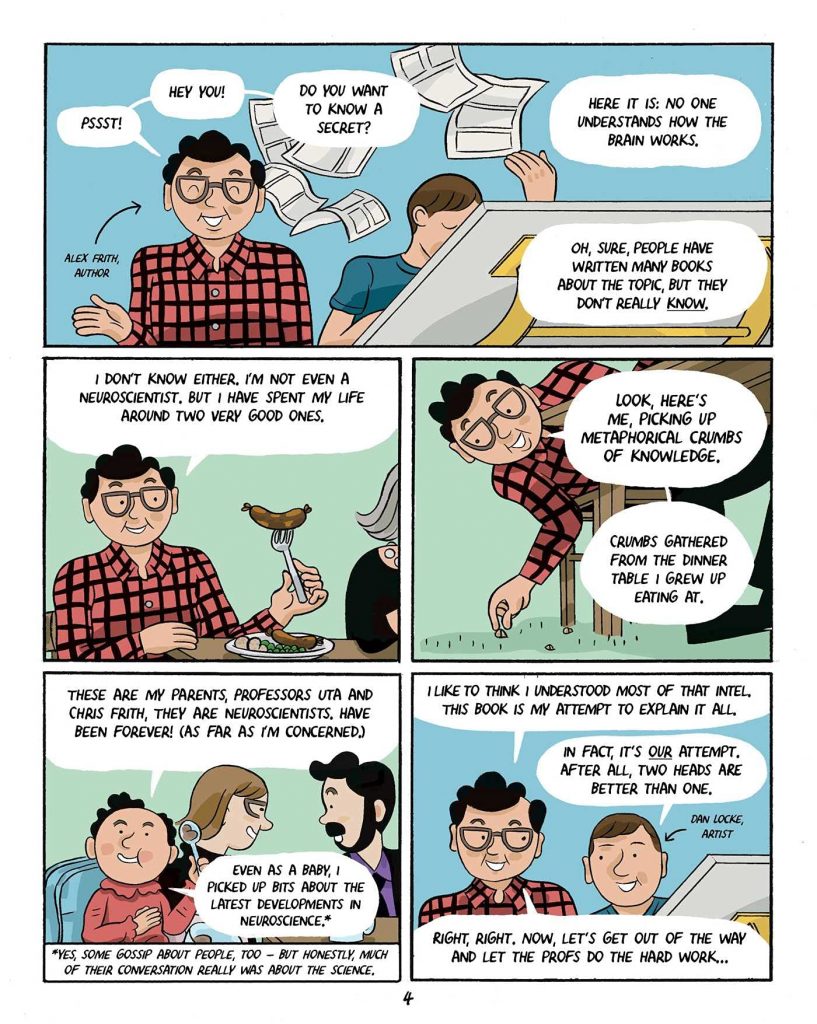

Near the end of Two Heads: A Graphic Exploration of How Our Brains Work With Other Brains, Alex Frith makes a rare appearance in the book. For much of the work, he has let his parents—Uta and Chris Frith—do much of the work explaining the science, but he shows up to comment on why the book is in a graphic format. When Uta, his mother, addresses the reader to admit they might be wondering how “this comic got published,” as “it’s pretty niche, as comics go,” Alex argues that “it’s because the world is finally ready to notice that nonfiction is made easier to understand—and more fun to read—as comics!” (284-85). His comment made me wonder who the audience for this book is, a question that runs beneath the surface and structure (and format) of the entire work, and one I’m still not quite sure about.

It doesn’t seem to be aimed at people who know comics (or graphic nonfiction, which is what most readers familiar with the genre would probably use). Throughout the work, the Friths draw attention to the fact that the work uses a graphic format, ranging from notes on what to notice in the background of certain panels to direct addresses to the reader about why they’ve chosen this format. There’s also at least one inside joke to comics history, as the authors compare their beginnings in the field to how Batman chose his particular image, complete with a footnote apologizing to Bill Finger and Bob Kane. Anyone who’s familiar with comics history, though, would get that joke without the footnote, and anyone who regularly reads comics wouldn’t need the guidance the Friths seem to be providing the reader. The approach early on in the work seems to be teaching the reader how to read comics, on some level, which implies that the audience is people who are interested in the science, but who might not know much about comics.

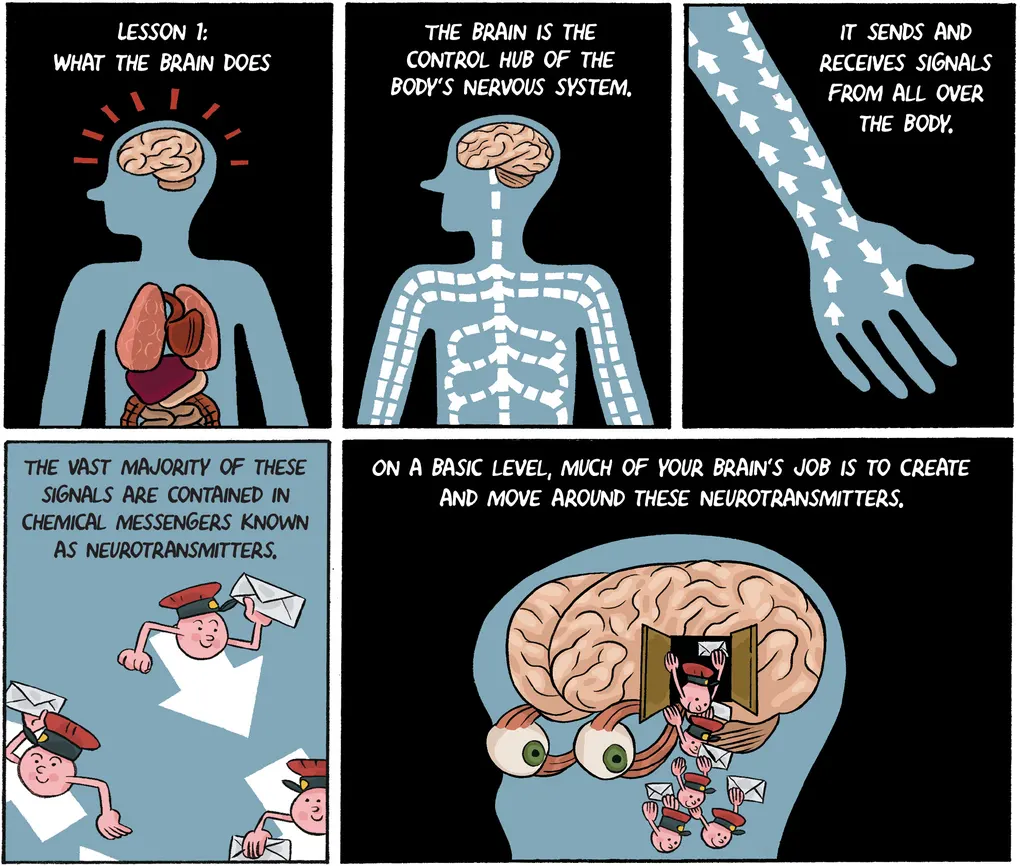

Additionally, the layout of the book is easy to follow for anybody who’s not familiar with graphic nonfiction. The panel structure is no more complicated than anything one would find in the Sunday comics section, and the art mirrors that simplicity. The people mostly look more like avatars than the more intricate characters that readers of graphic works are used to seeing. There’s also little action conveyed through art, as most of the work consists of talking heads, though the illustrations of the various parts of the brain work well enough to convey those ideas, when necessary.

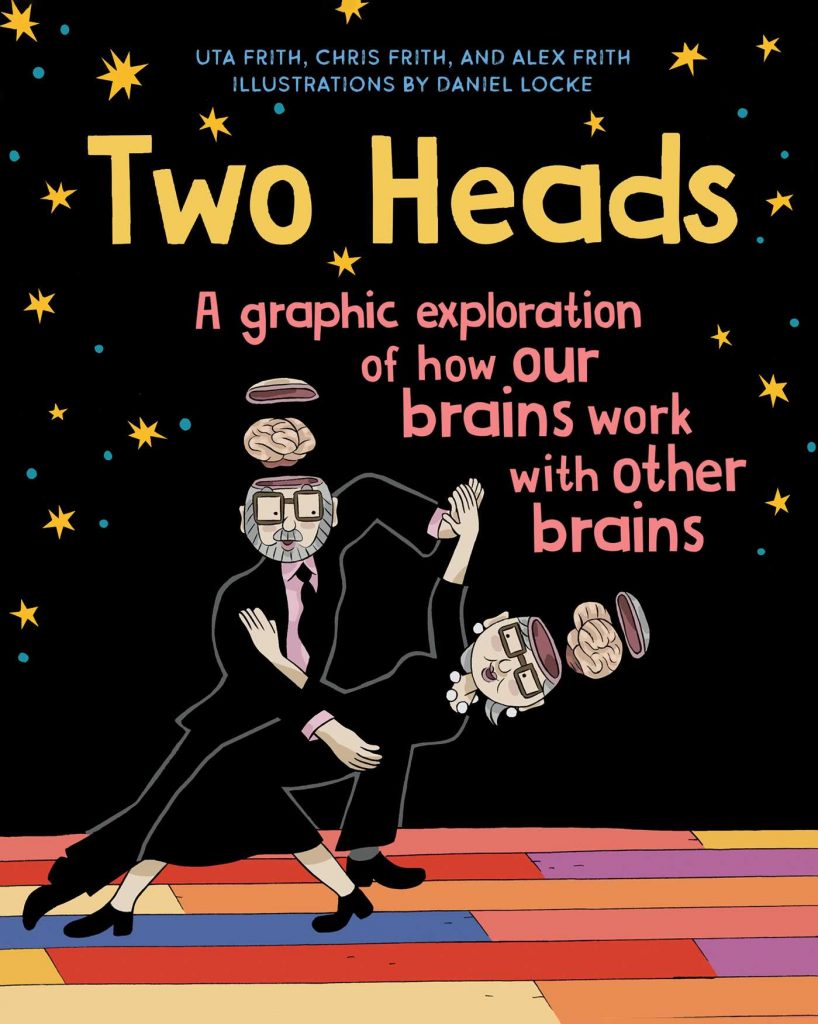

Please note, though, that none of my comments here are meant as a criticism. If the audience for the work consists of people who don’t spend their time reading graphic works, then there’s no need to complicate the work with an art style that’s going to make the work more challenging to read. Unlike most graphic works, the art here doesn’t seem to be on an equal footing with the text; instead, it works in service of the text. Even the byline on the cover says, “illustrations by Daniel Locke.” The word illustrations should tell us that we’re reading a work of neuroscience with pictures, not a graphic work about neuroscience.

That distinction raises a question about genre, in general. Graphic nonfiction usually falls into two main categories: graphic narrative nonfiction and graphic informational nonfiction. Some works blur those two lines, as Two Heads does at times, but the overall distinction holds true. For example, there are graphic narrative nonfiction works like the March trilogy that are clearly based on historical, nonfiction events, but tell the story in a more narrative manner, much like a novel would. There are character arcs and plots in those types of works. Graphic informational nonfiction is more along the lines of Wake: The Hidden History of Women-Led Slave Revolts or, even this book, Two Heads, in that they originate in the academic world, but then use a graphic medium to reach a wider audience. There are exceptions, of course, to this binary. The recent work Fine: A Comic About Gender, for example, lives more in the middle in that Rhea Ewing interweaves their personal story with a variety of interviews with others.

I’m not trying to make a value judgment here as to which of these formats is better, but without the distinction, we make the mistake of lumping all graphic nonfiction into the same category.

The purpose of a work like Two Heads, then, isn’t to push the genre constraints of graphic storytelling. Instead, the authors are much more concerned about having a larger audience understand their argument that brains work better when they work with other brains. Even here, though, I’m a bit puzzled by their approach. That argument doesn’t develop until well into the second half of the work – as much of the first half or more lays out the background to get to that argument. The Friths, here, could be taking a typical academic approach, in that they spend a significant amount of time providing a review of the literature, laying out what is already known about the subjects related to the argument they’re making. In a traditional academic article, researchers typically take such an approach to both give credit to the work they’re building on and provide credibility to the argument they’re about to make. Since the Friths are both academics, such an approach makes sense, given that they’re drawing on their years of research in this work. However, it’s not a typical approach for a nonfiction work aimed at non-specialists, which seems to be the audience, given the graphic format.

If one is fairly fluent in how the brain generally works, though, the first half of the book feels fairly redundant. If one doesn’t already have that knowledge, then the first half serves as a solid primer for people who might be interested both in the Friths’ argument and in learning about other areas of research, as well. This focus on an audience that needs such background also explains why they would use a graphic format, as they’re trying to entice people to learn more about the subject, in addition to convincing them of their argument. The question that remains, then, is whether this format is, as Alex Firth argues, “easier to understand—and more fun to read—as comics!” (285).

As to the first part of his assertion, thanks to the graphic nature of the presentation, I definitely was able to follow the experiments they discuss and the conclusions they draw from those experiments. Having illustrations of the brain to help understand its various parts (and how they go wrong) is also helpful. I don’t know, though, if the graphic approach is easier to understand or if that was simply the medium in which I encountered some of these experiments and ideas for the first time. Perhaps the Friths could have simply written a nonfiction work for non-specialists in prose, and I would have understood their ideas and arguments perfectly well? Since there’s no prose work to compare their graphic work to, it’s difficult to judge if this format, in fact, makes it easier to understand.

The second part of Alex Frith’s comment, on the other hand, the “fun” part, is a more difficult argument for me to agree with. I’ve read enough popular books on neuroscience to say that I haven’t found any that were fun or even compelling from start to finish, save for the fun that comes from new ideas. Honestly, though, most tend to sag in the middle and would work better as articles, not books. Two Heads feels like that type of work. There are parts that fascinated me, especially the chapter on how people with autism function differently (which also included a nice reminder that the term neurotypical is problematic, as there’s no such thing as a typical brain). Essentially, the interesting parts of the book center on what happens when people’s brains don’t work in the same way as the dominant view of how brains work leads us to think they should. As with many nonfiction works, I wanted to see less material to set up their argument, but also more interesting material. If readers are looking for a graphic work on neuroscience that provides a solid background on the subject and an interesting argument by the end, Two Heads is a good way to spend a few hours. If they’re looking for groundbreaking work on the graphic format or a deeper understanding of neuroscience, they should probably look elsewhere.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply