I think about zines a lot.

The word “zine” means a lot of things to a lot of different people, and what was once characterised as an accessible and necessary means of communication for marginalized groups (punks, anarchists, AIDS activists, or female Star Trek fans, for example) is now a friendly and prolific part of the comic festival industry. The Fest scene is often criticized for its participation barriers, including table costs and accessibility; and it doesn’t seem very punk when people use the word “zine” to describe anything from the traditional photocopied pamphlet to a glossy, full color volume. This leads on to question, are “true” zines dead?

No, of course not, and I’m absolutely not interested in defining the word zine in 2020. I don’t think that act is productive; I don’t care what makes one booklet or another a “real zine.” I’m not above the conversation, it’s just not what I find interesting about zines.

What I do find interesting is the way both the spirit and the physical body of the “real” zines of the past survive today. Both how they continue to be present even in the privileged space of comic festivals, but also how they survived the tumultuous movements and moments they recorded. Zines — cheap bits of disposable paper — are vulnerable to time in a way other media is not.

So when I got to dig through an exhibit of radical zines from 30 years ago, I was predictably grateful. But I also came away with an unexpected gift: a renewed appreciation for the zines of today.

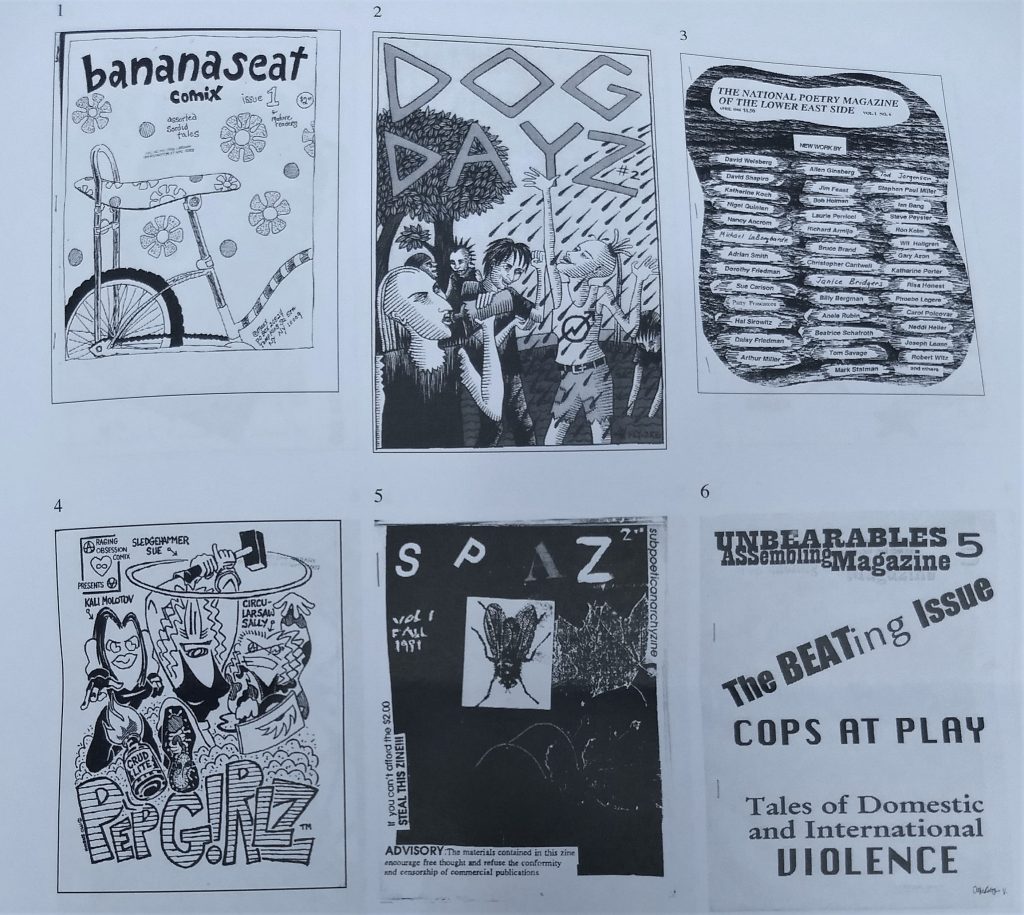

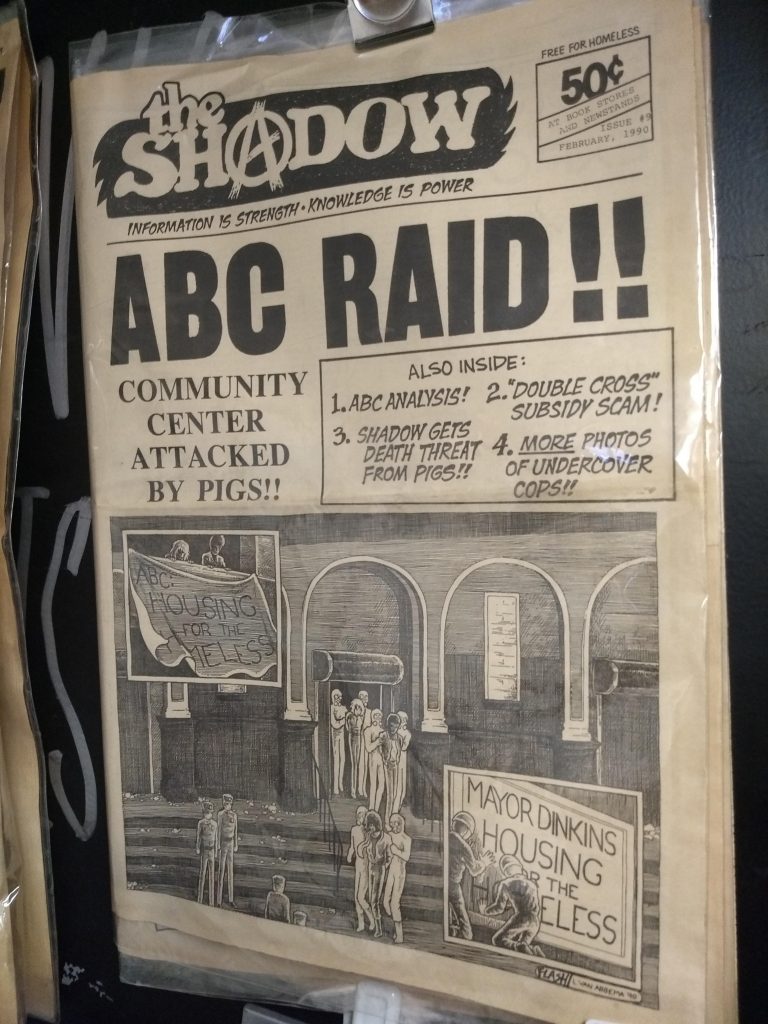

In the summer of 2019, the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space held an exhibition called History in a Box: 1980s & 90s in Community Newspapers and Zines, ABC No Rio in Exile @ the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space. While the exhibit consisted of photocopies of the materials on the gallery walls, the important part of it was the history in the boxes: in the southwest corner of the gallery were stacks of archival boxes full of 25-35 year old zines that you could actually thumb through, provided your thumb was covered in the provided white handling gloves.

Through sheer luck, the show was still on display the week I was in New York City for the Queer Liberation March (an event distinct from the Pride Parade, though I went to that, too) even though it was scheduled to come down a week earlier. I’ve never had the opportunity to hold a history so specific to my interests and identity in my hands. I don’t know that I ever will again.

ABC No Rio was an alternative art and activist space founded in 1979 in the Lower East Side of New York City. Their zine library was formed when the organization rescued the Blackout Zine Library from an endangered South Bronx squat. Now that ABC no Rio is closed pending a complete renovation of their space, which was only permitted after years of fighting to keep from being evicted, the library and other facilities live in separate “exile” spaces. The MoRUS facilitated an exhibition celebrating those materials that would otherwise live quietly in exile for several more years. The content of this collection is authenticated by its journey, evicted and rehomed as so many alternative spaces are.

The collection was even more breathtaking than I imagined it would be. I sat for hours methodically flipping through and photographing zines that took me back in time to a place that fascinated me.

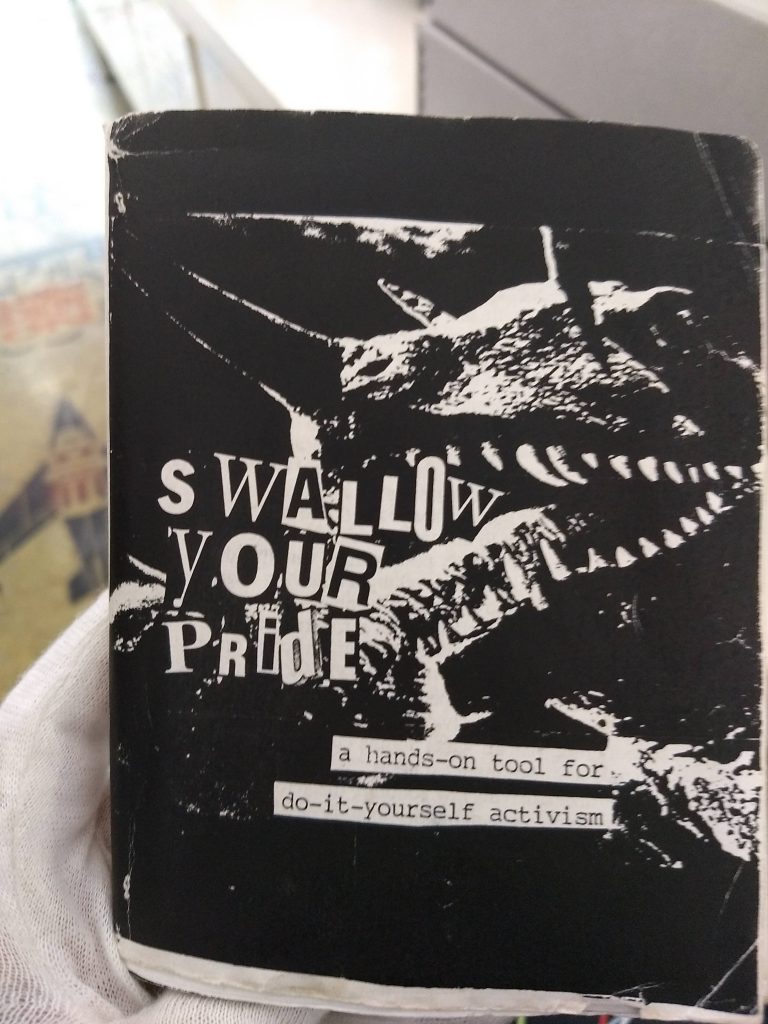

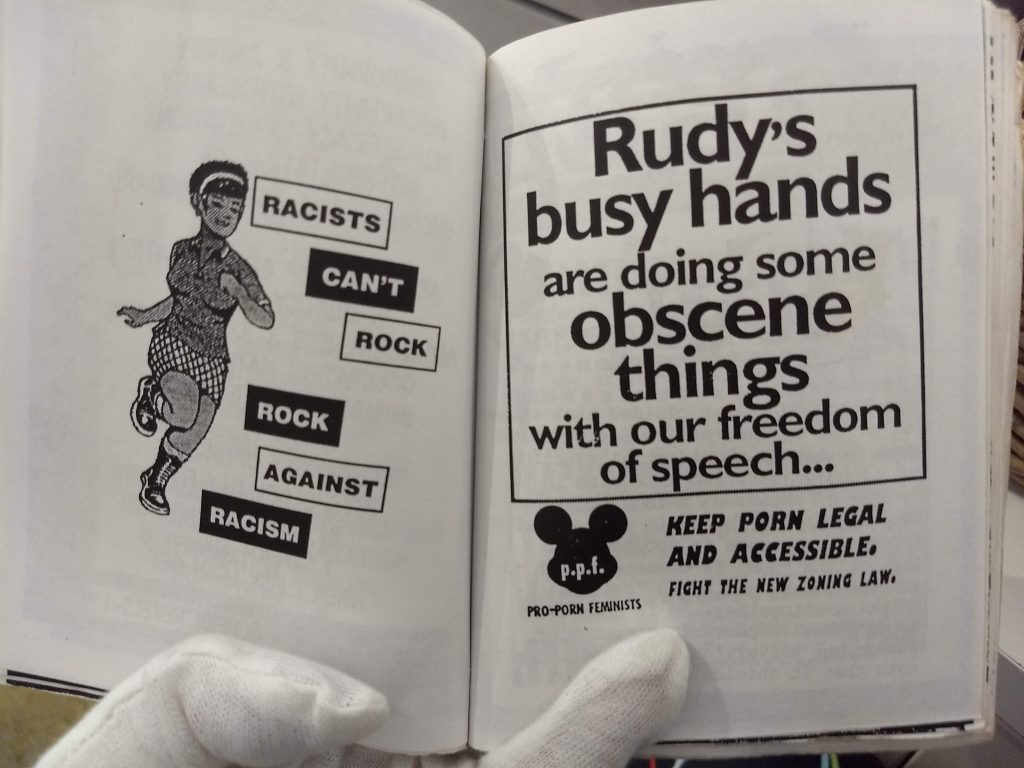

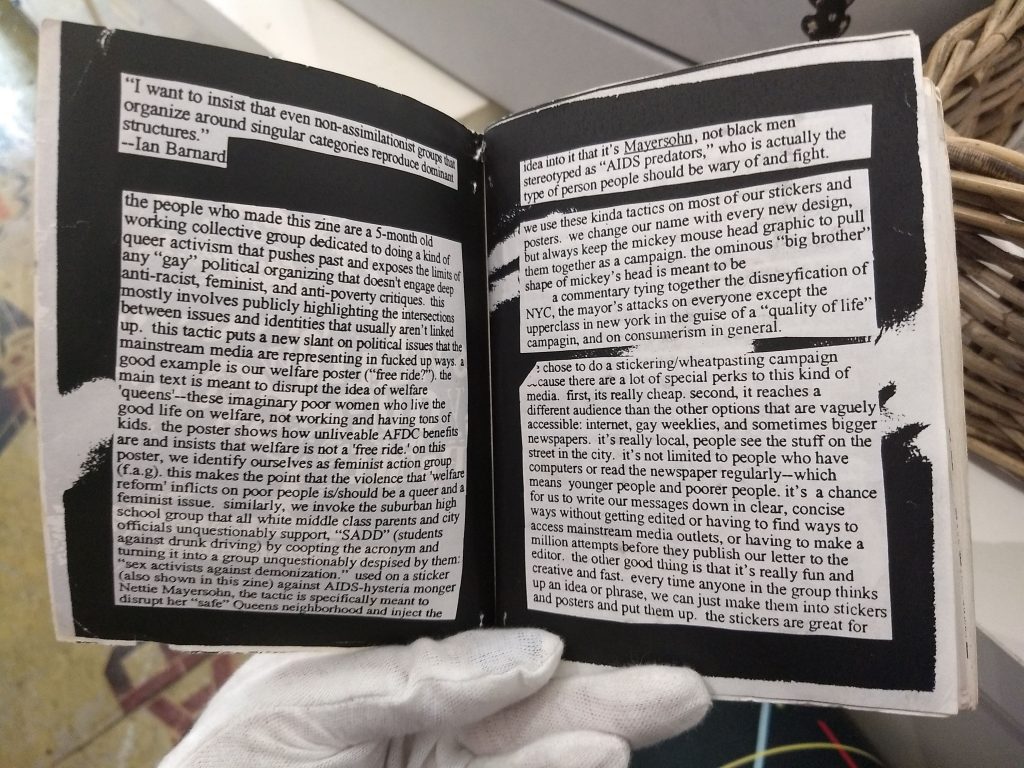

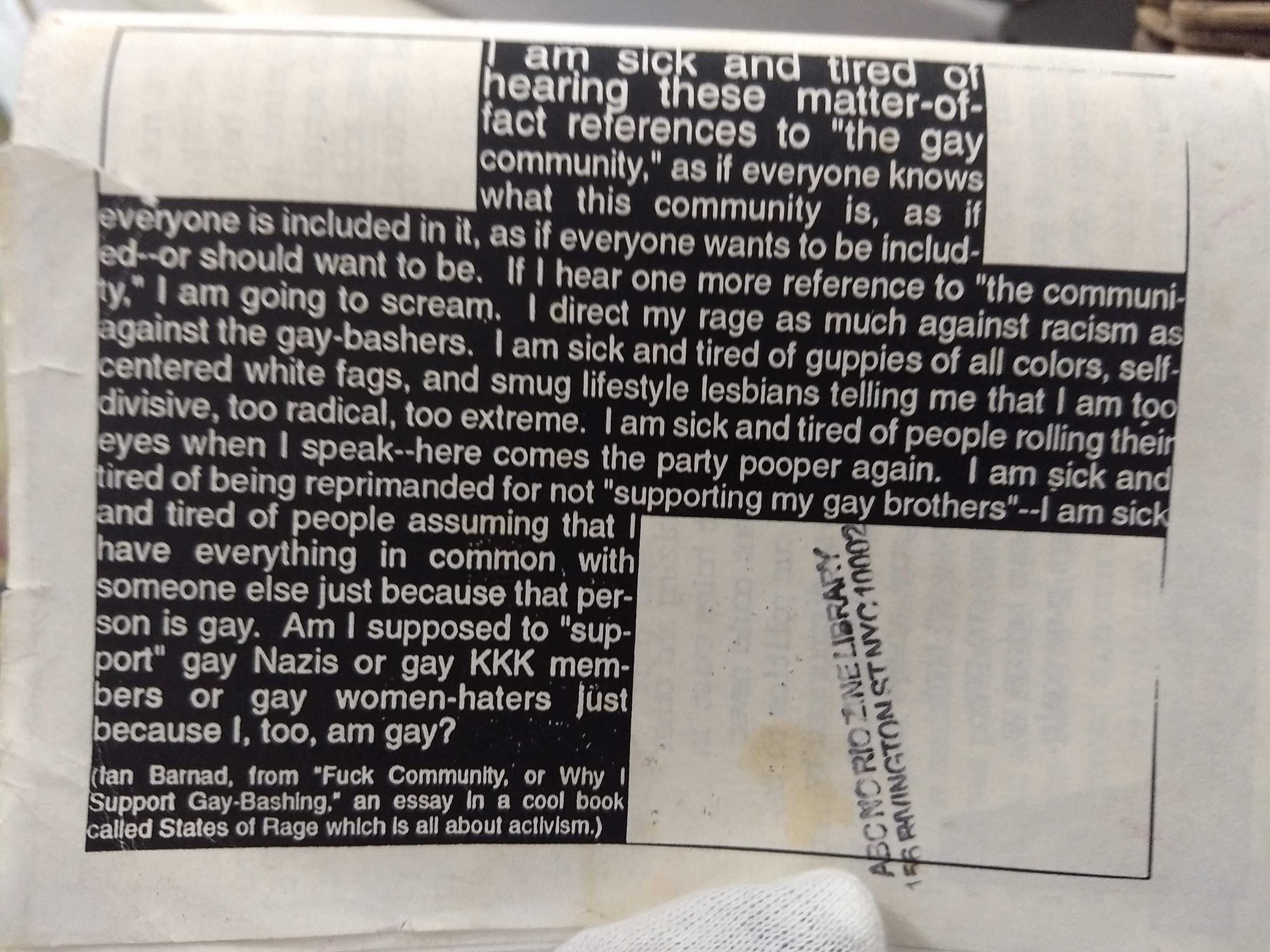

I was instantly taken with a zine titled SWALLOW YOUR PRIDE: a hands-on tool for do-it-yourself activism. This quarter-tabloid sized, 60+ page black and white xeroxed book is both a tactile delight and a whirlwind ride through art and writing about activism around racism, sexism, homophobia, pornphobia, and homelessness. Though the staff was unable to date the piece for me, the recurrent rants against Rudy Giuliani’s mayoral influence probably puts its publication in the mid nineties.

A lot is said about the divisions within activist communities these days, and for good reasons. It’s unproductive to approach activism without a meaningful consideration of intersectionality, but it’s also dangerous to ignore the ways in which hierarchies and discriminations crop up inside activist spaces. But as that conversation develops, it’s stunning to see a single community volume that addresses so many issues of social marginalia without a hint of internal animosity. The rage in SWALLOW YOUR PRIDE is directly focused on the systemically oppressive structures and at the layers of colonialism that result in the need for a book like this.

That’s not to presume that 90s activist communities were somehow more united or less oppressive than today (that would be ridiculous,) but this zine is a gem that imagines an excitingly equitable activism that might be impossible to recreate in our current climate.

SWALLOW YOUR PRIDE exemplified the exhibit for me, but it was far from representative of it.

Nearly every zine I touched was small and photocopied, crude and angry, and tucked within them between copies of newspaper clippings, photo collages, and typed screeds was the occasional comic. Being a cartoonist and invested in the power of comics, it felt like I’d caught a big, beautiful fish after hours of pulling up very pretty seaweed every time I came across one. Each comic was a moment someone said “I need to tell this part of my story with words AND pictures and the only way to do it right is to draw it myself.”

Delivery Dyke, by Suzy Subways, is made out of side-stapled letter-sized paper with color added to the covers by hand using crayons or colored pencils. It was easily my favorite piece in the collection, as it is a fascinating portrait of a woman with a dangerous job in a rough place at a difficult time. There are essays, drawings, comics, and news clippings littered with rich, scrawled commentary. It’s like a scrapbook that tells me who this person was at that moment, what she cared about, and what she wanted. In a scratchy comic drawn in pencil, she shows us her sense of humor and her personality. She’s the delivery dyke. She makes deliveries, but also: she’s gay.

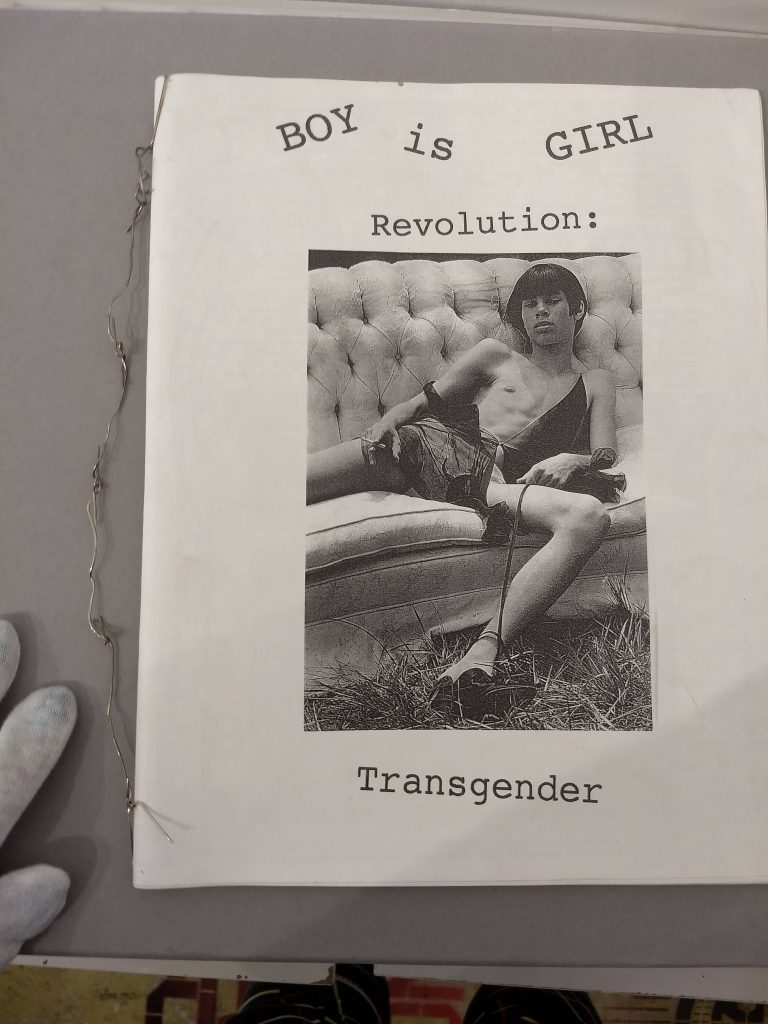

I discovered a few great comics in Boy is Girl Revolution: Transgender, a fabulous half-tabloid book fastened together by rusty, sloppily chained paperclips.

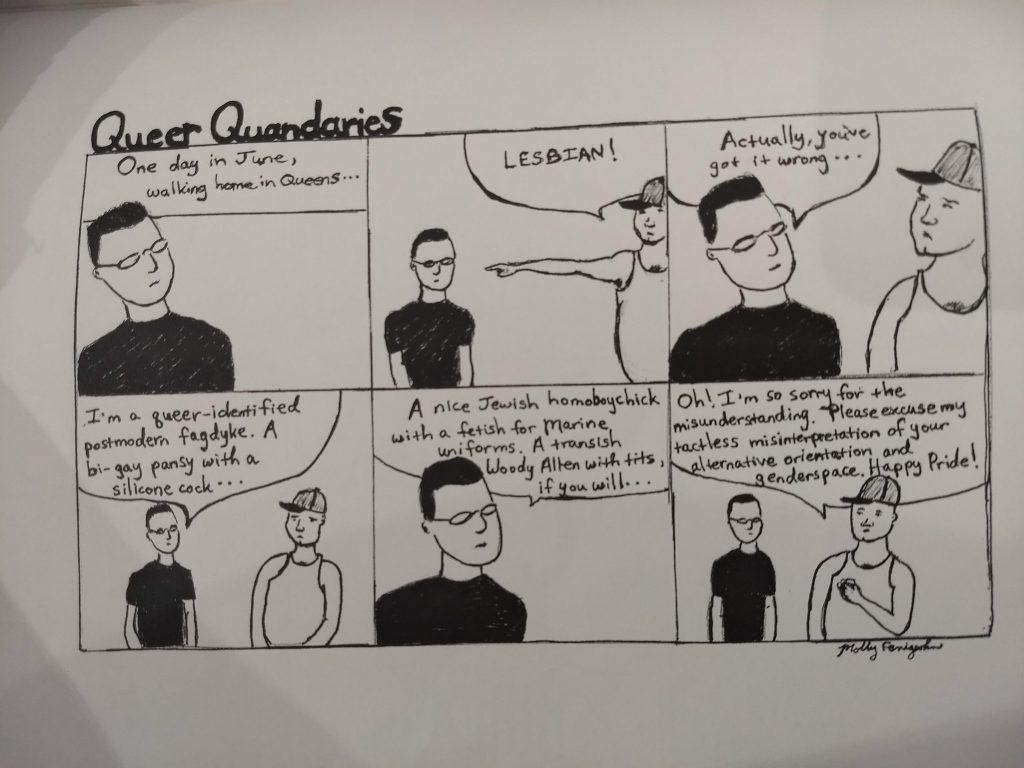

Delightfully relevant in the year 2020 is this strip comic called Queer Quandaries by Molly (last name unclear.) It’s a genuinely funny comic with a relentlessly exhausted voice. In it, the main character has what is presumably a fantasy interaction with a person on the street in Queens. The main character is a visually coded “lesbian” and the stranger is coded as a conservative-reading workingclass everyman type. With the stranger pointing and shouting “lesbian” at the main character, it’s easily read as an agressive interaction. But the main character then lists off a paragraph length clarification of their identity, full of obscenities and contradictions and specificities, that feels hilariously real to any queer person who has tried to describe their complex reality with words. It is then that the stranger gleefully apologizes and wishes them a happy Pride. The humor is layered and lands firmly in “there’s no way this interaction could happen. It’s too smooth, too satisfying, too without confrontation.” People who read queer in public still get assaulted and murdered on the street today, decades later, and this taps into the dramatic irony of us knowing this can’t be real.

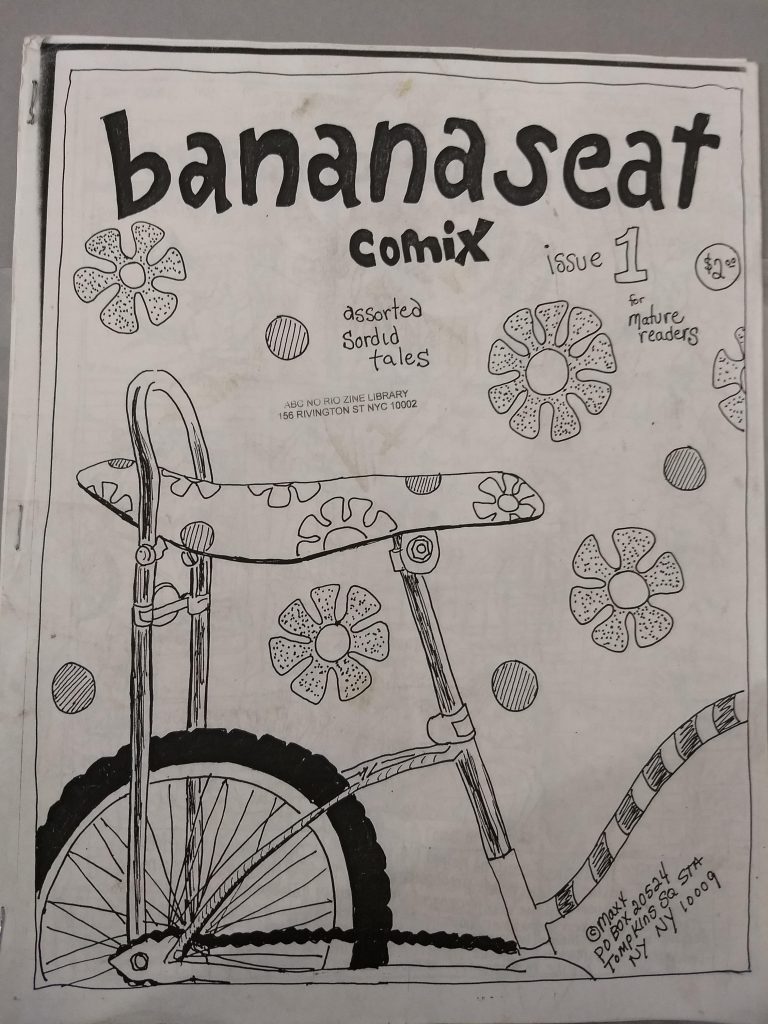

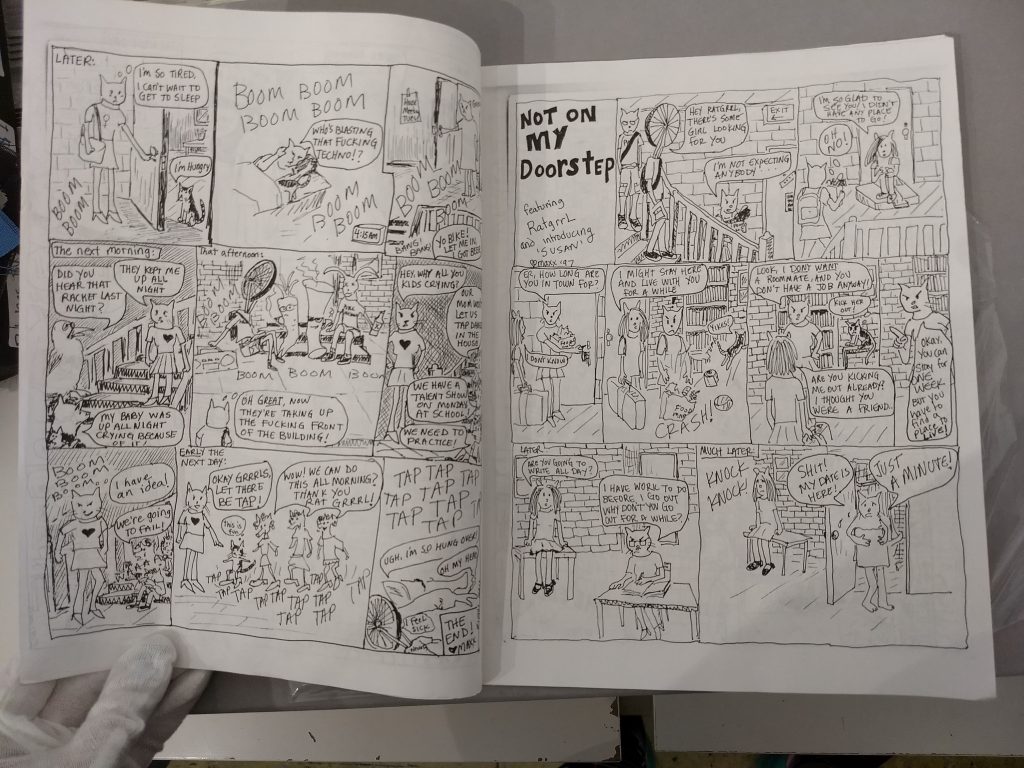

The Ratgrrl comics in Bananaseat #1 by MAXX (dated ‘97) are delightful. In their depiction of a queer tenant trying to survive their own raucous community — between noisy visitors to the drunk downstairs neightbor, her own pushy “guest” that overstays her welcome, ticketing at a club, and visiting aliens — these comics are all deftly channeled, truly inspired rage. They’ve got Roberta Gregory energy; just a straight documentation of all the ways the universe has set out to annoy you, individually, in particular. Even in a fantasy version of the Lower East Side populated by humanoid animals and objects, we feel the frustration with a community that’s forced to occupy a space too small and too unequipped for it.

I can’t describe the entire collection I saw at the MoRUS, obviously, but the three hours I got to spend with it left me wanting to spend days more peering into this graphic universe that came to be when I was just a little kid toiling away at middle-school academic overachievement in rural Pennsylvania.

I’m not in a position to compare the reality of zine making in the Lower East Side 1990s to its environmental equivalent today. I’m not on the ground in any marginalized communities — I’m a working class white trans person who struggles a little, helps (in safe ways) a lot, and fights (in dangerous ways) far less than I should. So I don’t have the experience or the knowledge to make any judgements about how zines are less punk or raw or real now. It’s not my space, it’s not my voice.

But that’s not to say the authentic grassroots anarcho-punk voice of these kinds of zines is absent from the fancy comics festivals I do attend. Though the rightly-contested monetary barrier for participation in comic fests exists, marginalized voices find ways to infiltrate it and be known. Their voices are not identical, but the spirit is the same.

At the Small Press Expo in North Bethesda, Maryland a few months after my visit to MoRUS, my ears were wide open, waiting to hear those voices again.

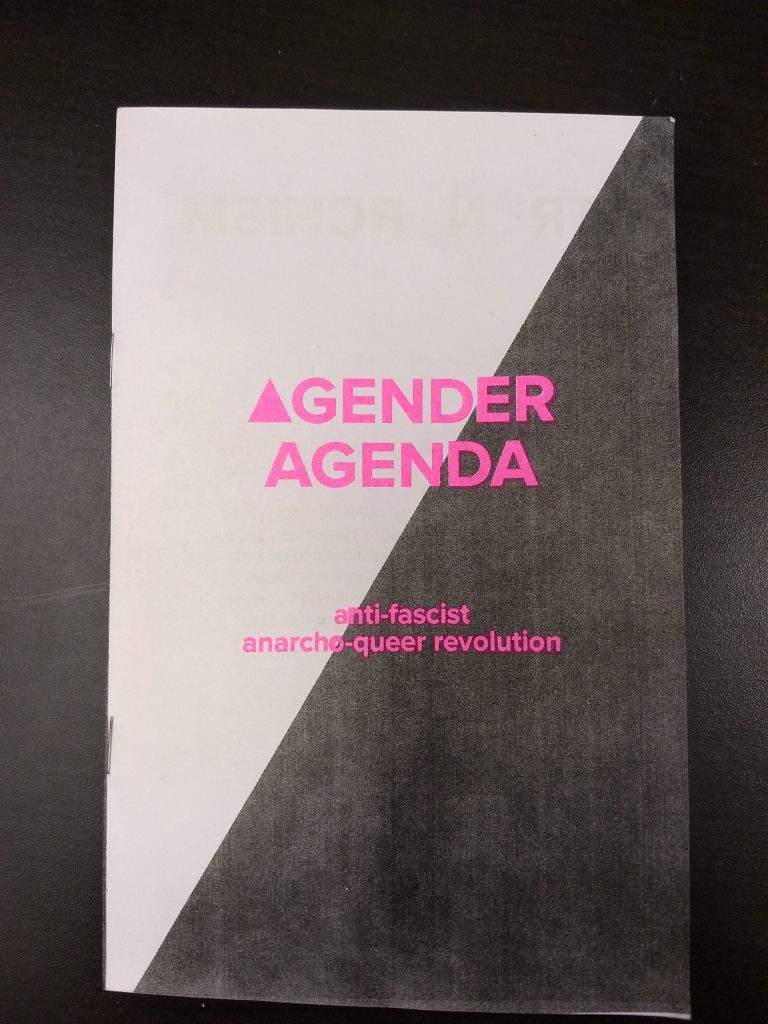

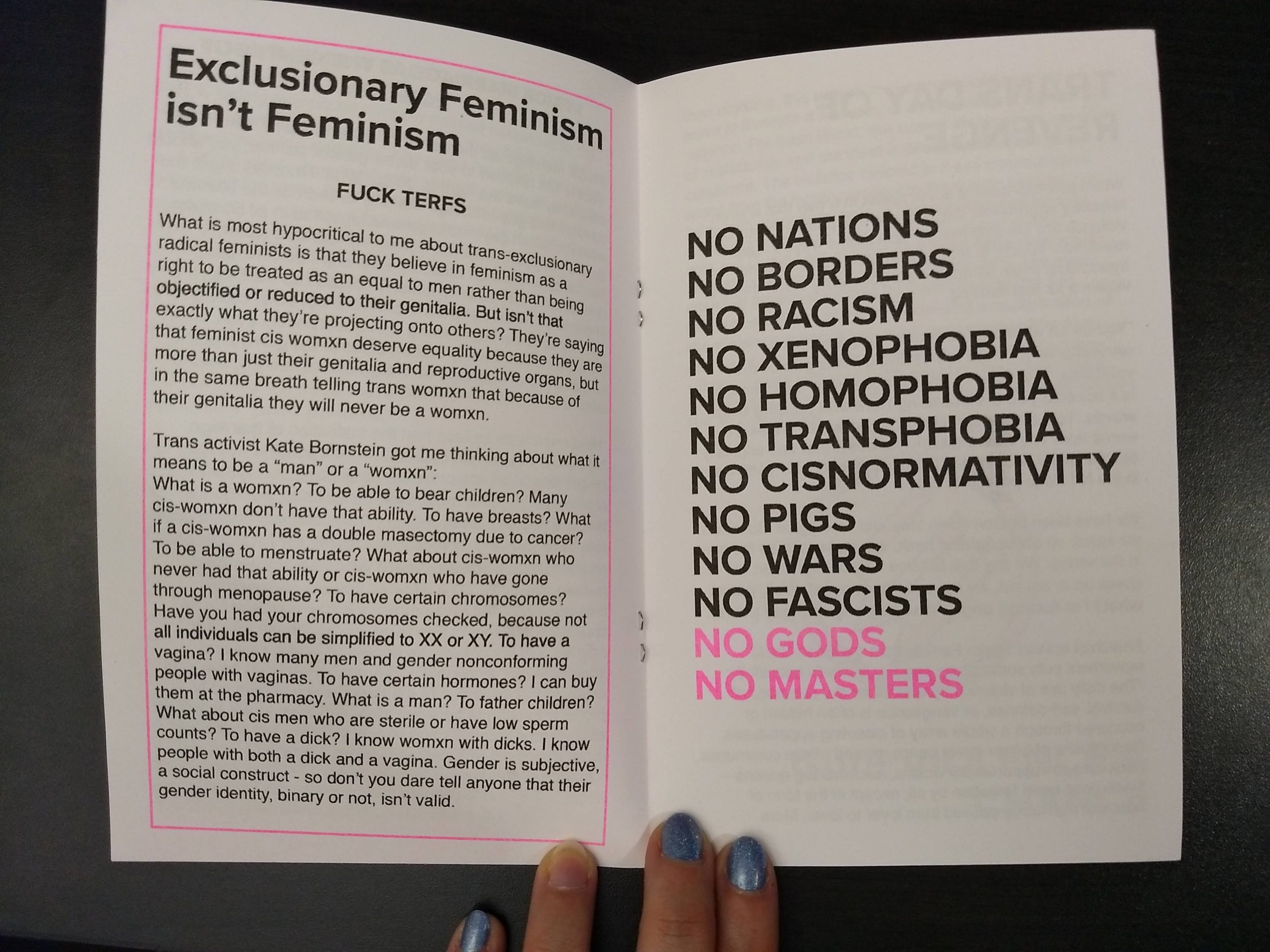

I picked up AGENDER AGENDA: anti-fascist anarcho-queer revolution by Seth Katz from Silver Sprocket as soon as it saw it. It screamed “I’M HERE TO COMMUNICATE MY QUEER DISCONTENT AND FUCK YOU” in a way that resonated with the tones of the books I saw at MoRUS. Though more tidy and designed, aided by a computer, and being sold at a comics expo with a ticket price, it echoed deeply with the tone of text from SWALLOW YOUR PRIDE, made decades earlier. With a “sit the fuck down and let me tell you how it is” attitude, it is remarkably intersectional, aggressive, and exhausted with bullshit.

Hours later, working my own table at the show, a young person approached my table mate Melanie Gillman, told them how much they admired their work, and asked to give them a copy of their zine. Melanie, always humble and kind, insisted that they trade, an act that delighted the youth. Sneaking a peek at the zine, a side-stapled, photocopied book titled ACT UP! by EVT, I rudely waved them down and asked if they wanted to trade with me, too. They kindly obliged.

This zine is phenomenal. Drawn on lined paper and photocopied without computer adjustment onto single-sided pages, this book vibrates with the alternative production energy the MoRus collection had. It’s a history zine, in which EVT wants us to know about Act Up, Garance Franke-Ruta, and the AIDS crisis. It’s raw, enthusiastic information. It’s the desire to communicate — desperately — a history they need us to remember.

Considering that history, the environment of the 2020s comics festival is drastically, absurdly different than the squatted-in alternative spaces of the 1990s. There are still countless artists working within the comics system to educate on and normalize marginalized stories and perspectives. The aforementioned Melanie Gillman is a prime example, making comics on the web, keeping journal comics, drawing award-winning graphic novels, and writing for commercial properties like Steven Universe comics. They, and everyone making glossy, queer diary comics, angry queer risographed books, or foil-stamped queer hardcover tomes are doing important work. Seeing radical queer voices pop up, using historically radical queer formats, in contemporary spaces that are not extremely radically queer is exciting and inspiring too.

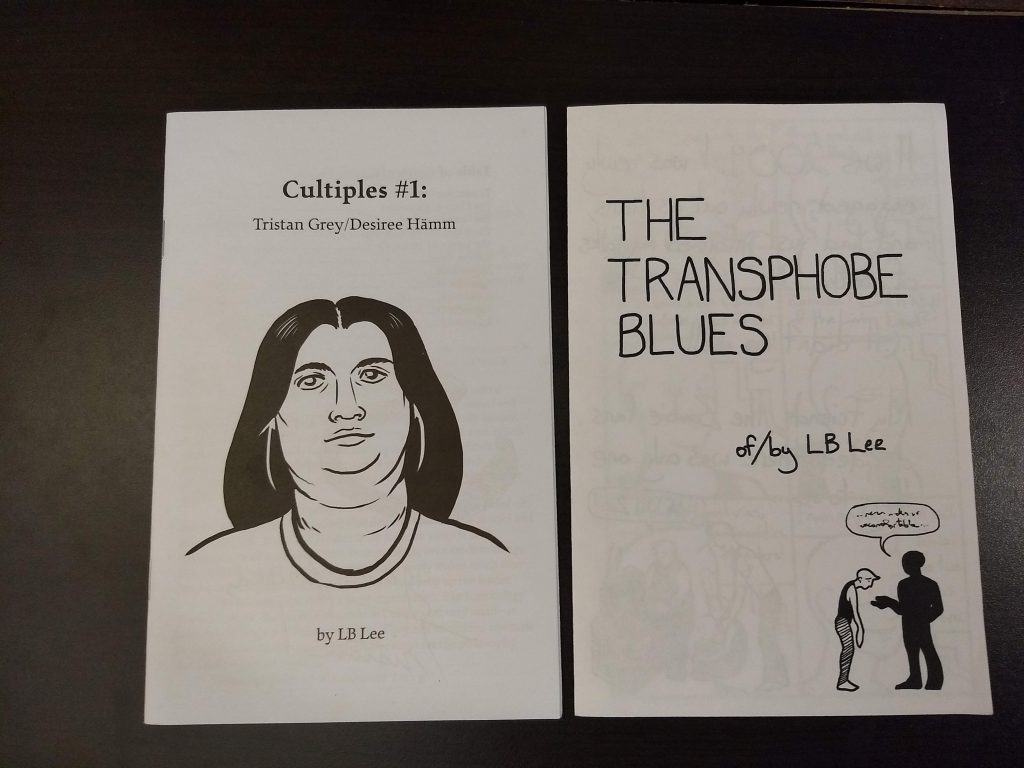

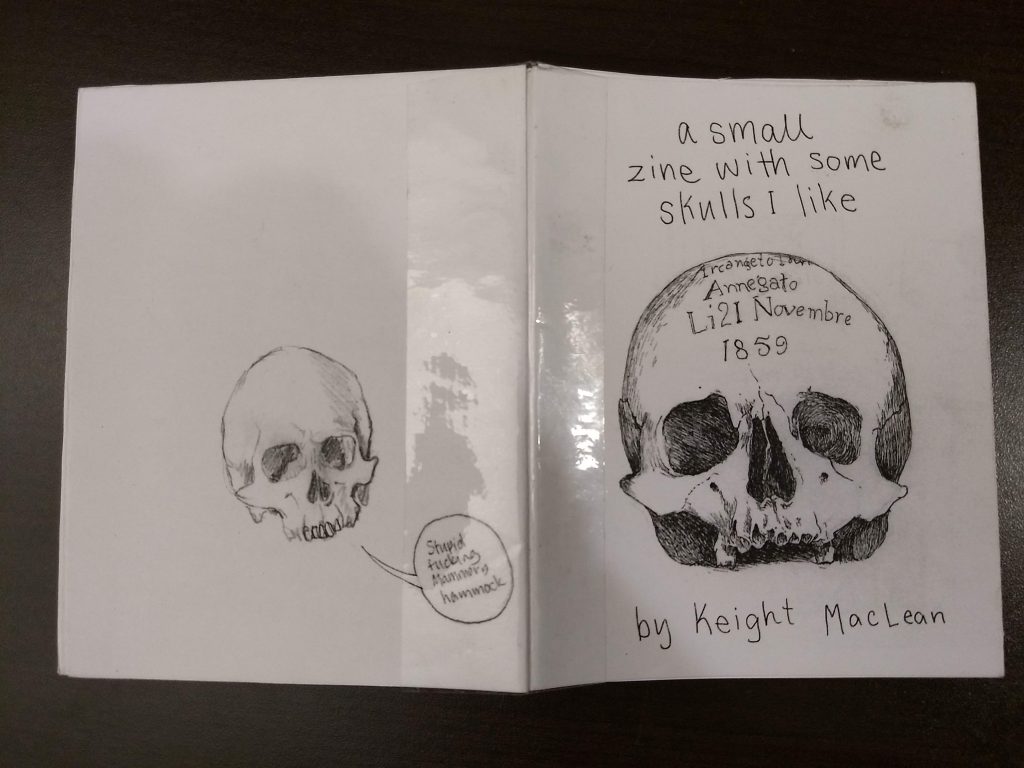

I see it in the work of LB Lee, hawking low-cost zines about transness and plurality in the same spot at the MICE Expo in Cambridge every fall. It’s in the photocopied zines of Archie Bongiovanni I got at Flamecon in Manhattan last summer. It’s in the zine, small and bound with packing tape, titled a small zine with some skulls I like by Keight MacLean, that I feel the energy of Delivery Dyke and the whole MoRus exhibit. There is still that desire to inform your community, cheaply and efficiently and accessibly, who you are and what you need them to hear.

Seeing the History in a Box exhibit gave me a renewed excitement for alternative zinemaking and a fresh perspective on the spheres in which we make alternative comics work. I’ve been thinking about it for months now, long after the collection has been packed back up and stored away, about how we use our creative energy within the parameters of the environments in which we live. It reinforces, to me, that good work is done on multiple levels.

The presence of those foil-stamped graphic novels and commercial-tie-in comics don’t spell the doom of — or invalidate the existence of — the radical, photocopied, anti-oppression zines of the past. The spirit of them lives on, even, in our privileged comic-selling spaces.

While I still don’t want to debate what a “real” zine is, I do believe that the heart of the idea of the zine is communication. Where there are less resources and more urgency, zines are cruder and more desperate to communicate. Where there are more opportunities and less danger, zinesters take the opportunity to express other things in ways that might cost a little more money and reach audiences with a little less at stake.

The ABC no Rio collection, a treasure trove of decades-old expression, may be back in “exile,” but the zines of today are still at our fingertips, in our festival-branded canvas bags, and even in our online shopping carts. In thirty years, will someone have preserved them, too? Will we be able to access the anti-fascist anarcho-queer zines of 2020 in 2050?

If the past four years have taught me anything, it’s that two things can be true at the same time. And right now I feel like it’s true that zine history is fascinating and important and must be preserved, but also, there are new and wonderful things happening to zines right now.

They’re not the same voices, but they’re our voices.

Support the reconstruction of the ABC no Rio home location at http://www.abcnorio.org/

Learn about the Museum of Reclaimed Urban Space at http://www.morusnyc.org/

You too can see the ABC no Rio Zine Library and other ABC no Rio in Exile facilities. Check out the calendar here for information: http://www.abcnorio.org/pcgi-bin/suite/calendar/calendar.cgi

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply