It is fascinating to observe the career progression of Corinne Halbert, an artist who externalizes grief, trauma, desire, and guilt into lurid horror comics and paintings that center around religious iconography. In her earliest work, like Hate Baby 666 (2017), Halbert makes her intentions clear with the very first story, “Seven Deadly Sins.” Halbert fuses classic horror comics from the EC era with the schlocky and borderline pornographic horror/fantasy films of the 70s and 80s, along with a healthy share of Catholic iconography. The result is someone who used their Sunday school knowledge to make deliberately provocative imagery–clearly both for herself and the viewer.

Halbert basically has one mode: over the top and in your face, all the time. “Seven Deadly Sins” opens with Jealousy, and here Halbert draws two nude women clawing at each other, backed by another face and clawing fingers egging them on. Halbert then draws Lust as a semi-clad woman being penetrated by a cobra’s tail, a look of bliss on her face as the cobra almost grins. In Hate Baby 666, Halbert takes the BDSM elements inherent in Catholic iconography and lays them literally bare, with a woman on a cross being eaten out by another woman. Another strip features two nuns having sex with a filthy variation of “Hail Mary” as the text. Halbert also explores the connection between writing in hell (pain) and writing in pleasure, down to an image of a bound, naked nun being raked by clawed fingers. The images are certainly confrontational, but they seem to speak to a deep need to express these images and fantasies on paper. They feel more cathartic than sinister, as though they had an almost prayerful quality in an odd way.

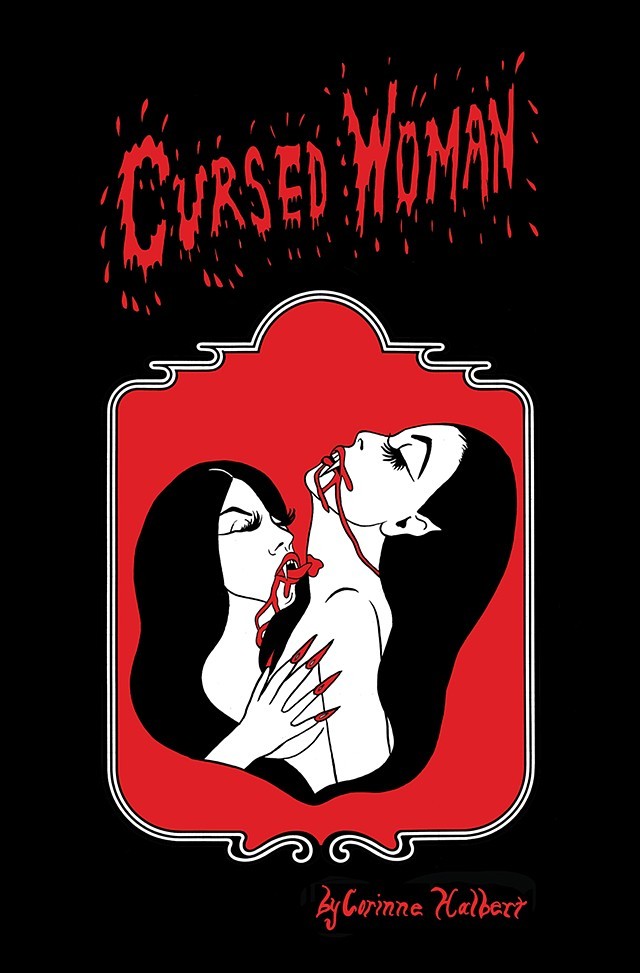

Halbert’s next work, Cursed Woman (2017), is a direct ode to the trashy horror films of Jean Rollin, and it highlights another significant element of Halbert’s work: psychedelia. The trippy quality of her comics makes the reader (and the characters) wonder what the line between illusion and reality is, even as reality seems to be falling apart. This is completely in line with the way that trauma erases solidity and certainty, and Halbert leans into it and embraces it. With “The Vampire Lovers” and “The Living Dead” girl awash in lurid reds and viscera, Halbert travels through familiar tropes with gusto. Here, we can see that her actual cartooning is not quite up to the level of her overall image-making. The panel-to-panel transitions and overall storytelling is stiff, even as the images themselves retain their power.

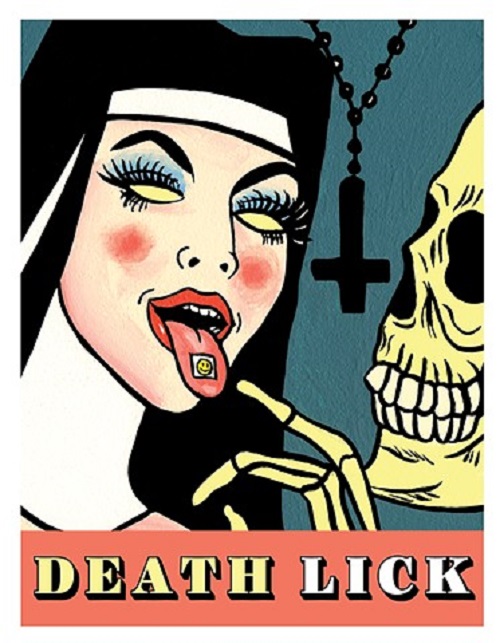

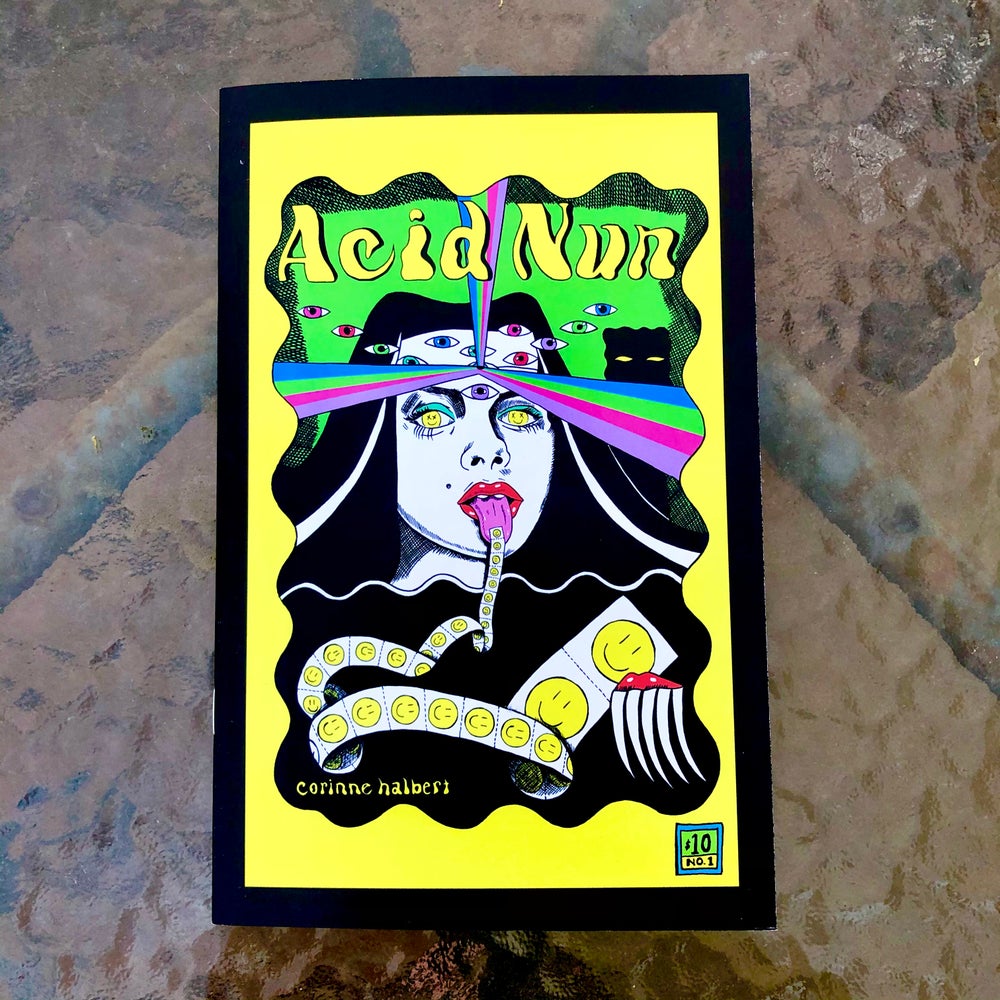

Death Lick (2018) features the first appearance of Halbet’s demonic nun dropping acid and cavorting with skeletons, as part of a series of paintings that lean even further into BDSM. The line between pleasure and pain seems to be related to the line between fantasy and reality (or perhaps sanity and madness) for Halbert, as her characters (sometimes wholesome, sometimes not) are bound, groped, licked, and stroked by skeletal or clawed hands. It’s a merging of Eros and Thanatos that dispenses with narrative and gets to the core of the fantasy.

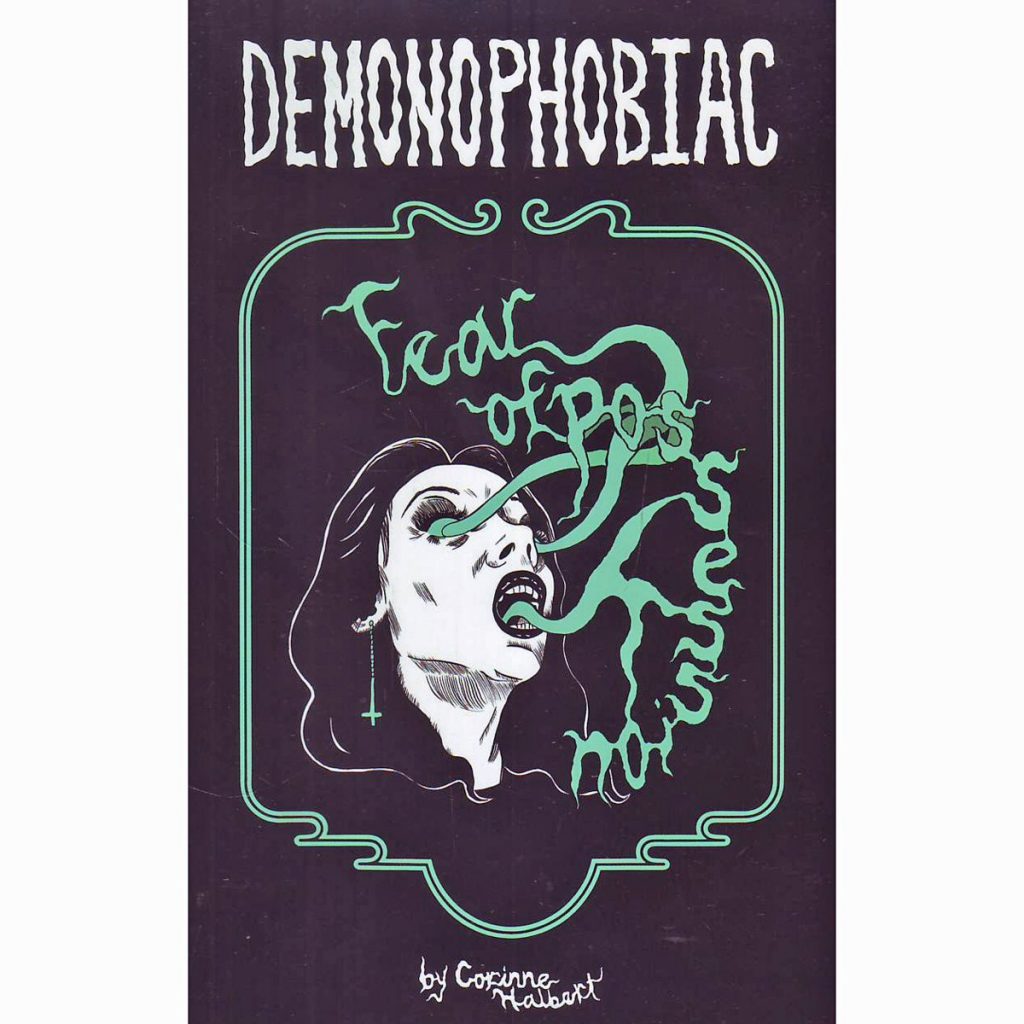

2019 brought Halbert’s first sustained narrative, Demonophobiac, and it’s a doozy. Built off her paralyzing grief over her father’s death, she inserts a thinly-veiled autobiographical character named Abby into the story who’s drawing a comic about her fear of demonic possession. As always, she heavily draws on bizarre horror films like Possession as fodder for her stories, but Halbert is much more than her wide range of influences. One can see Charles Burns’ influence in this comic with the way she uses blacks, but Halbert doesn’t have the same kind of slickness to her line. Indeed, despite her obvious skill as an illustrator, there’s an appealing roughness to her cartooning that deftly expresses the almost desperate depth of her emotions. Even in the scenes depicting quiet, quotidian events like Halbert at her drawing table, there’s an underlying tension where one wonders when the page is going to erupt with one of her more disturbing images.

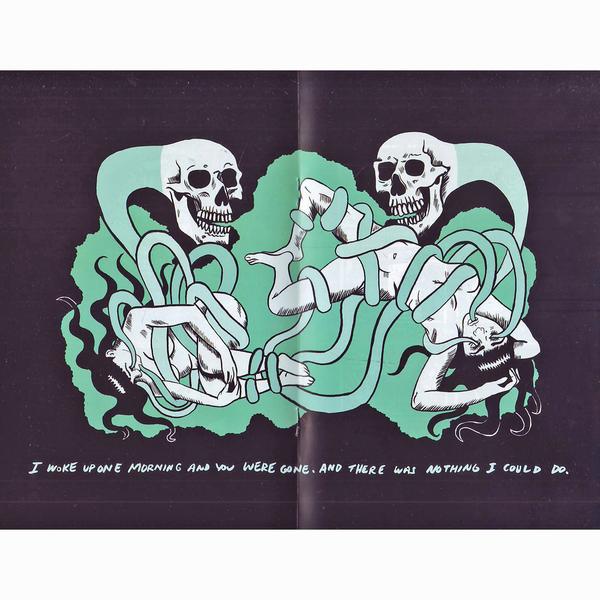

This eruption happens about halfway through Demonophobiac in the form of nightmares, and then there’s a jaw-dropping image of a perversely royal creature so bizarre as to defy description: the body of a spider and the heads of a frog, a cat, and a crowned demon or vampire. Total madness and/or possession follows as it is implied that her beloved husband would be her first victim. The fear of being possessed, the fear of having one’s body hijacked by a demonic force that makes you do terrible things, is a powerful metaphor. It’s not just a fear of a loss of control or a fear of mental illness; in Halbert’s case, it’s a fear of your negative emotions being so powerful that they overwhelm and transform you into an all-devouring monster. That’s how hard it was for her to process her sense of grief. As always, transforming fear and trauma into something monstrous on the page seems to be part of Halbert’s process.

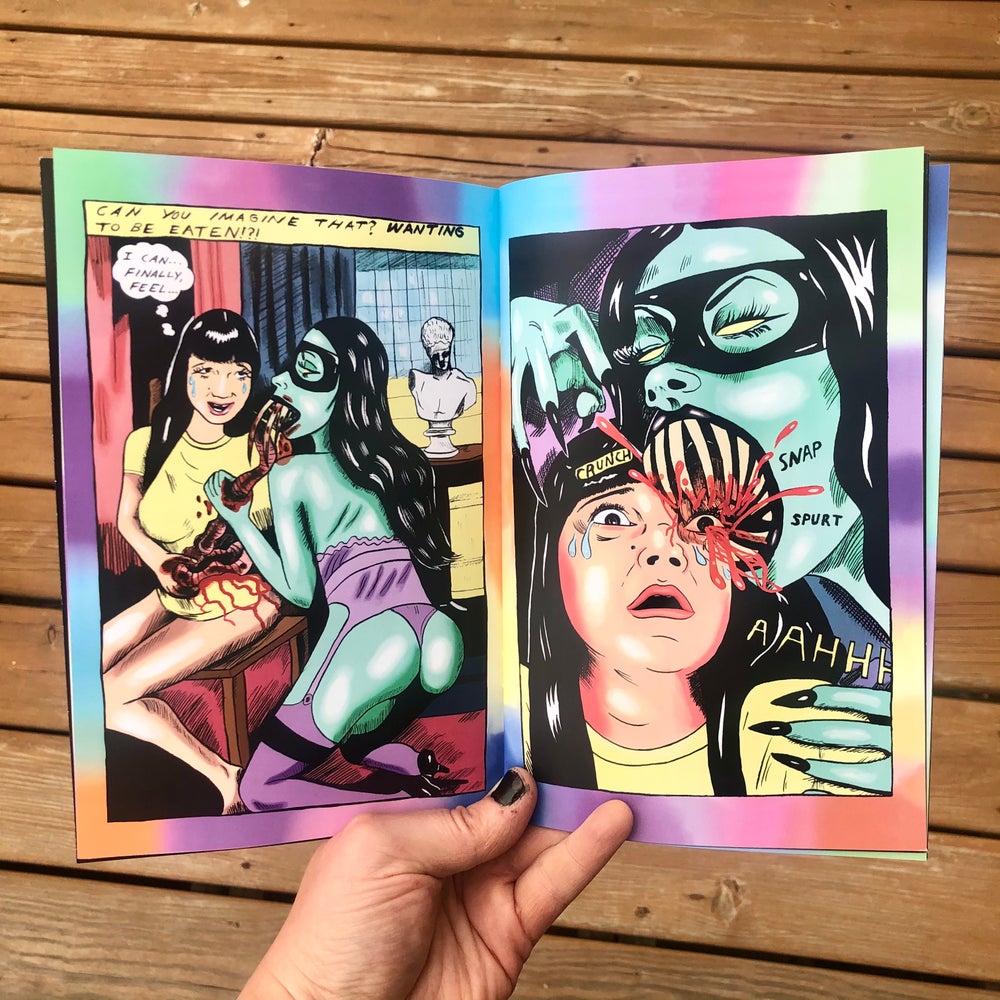

Halbert’s most recent comic, Acid Nun (2021), incorporates her psychedelic nun character into what can only be called a romantic quest narrative. Her partner is Eleanor, a horrifying, demonic creature with long teeth that extend out of her head. Halbert plays on traditional pornographic tropes by giving her a blue porn star body and this terrifying head that would literally devour its female victims. Halbert inserts herself into the narrative as a willing victim of Eleanor, thinking to herself, “I can…finally, feel…” as the demon is munching on her intestines. That’s a fascinating bit of nihilism, having her own creation devour her, yet it can be argued that Halbert is also the nun. Annie the acid nun incorporates all of that despoiled Catholic iconography and transforms it from something merely transgressive into something resembling a superhero. She tames the demon and earns her love, all while allowing reality to bend around her. If Halbert was terrified of losing control in Demonophobia, her Annie character represents letting go of her attempt to control reality and giving in to the psychedelic experience.

Inserted into the middle of all this is the shadowman Noah. With his cowboy southern drawl, he’s the epitome of toxic masculinity rearing its head, as he separates the lovers thanks to extradimensional interference. This wispy character with a black hat is simultaneously hilarious and terrifying, but he gives both Annie and Eleanor a force to work against. While the story ends on a cliffhanger, Eleanor’s quest to find Annie by way of summoning Baphomet is actually as conventional as it gets for Halbert in terms of story structure. It’s a noticeable shift in emotional tone as well. While Halbert’s imagery remains viscerally over-the-top, it seems to be more in service as establishing Eleanor and Annie as larger-than-life characters that are impossible for normal people to comprehend than the simple taboo-busting that marked Halbert’s earlier work.

An effective horror comic can be as autobiographical in nature as someone making quotidian observations about their day. In some ways, horror can be even more revealing, and that seems to be the case for Halbert. These are deeply personal comics where she shares her fears and transforms them into fantasies. In the face of the meaningless void and the negation that death brings, reifying and naming your fears can give you power over them. Manipulating them in a story and coming to terms with their ugliness as a part of you offers a similar degree of control. Every devoured victim, every unholy and perverted sexual act, each shattering of a religious taboo serve as meaningful images for Halbert, who isn’t trying to shock an audience so much as grapple with her own demons. As such, some of the images are so ridiculous that it’s clear that she’s laughing at these demons as much as she is afraid of them and turned on by them. She takes the audience on a ride with her and invites them to laugh, shudder, and get turned on as well.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply