It was lunchtime at the Woolworths in McComb, Mississippi. It was a hot day, August 26, 1961, and men and women were enjoying their meals and conversation. It was a busy day. All the stools were taken at the counter. When two spots opened up, Hollis Watkins and Curtis Elmer, two young Black men, filled them. The server ignored them. Nearby diners began to get agitated by their presence. The police were summoned. There were Jim Crow laws to uphold. The young men were asked to leave. They refused. They were immediately arrested and removed. Both men had comic books in their possession upon their arrests.

It was dinnertime at the Woolworths in Greensboro, North Carolina. It was a cold day, February 1, 1960, and men and women were enjoying their meals and conversation. Four young Black men, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Ezell Blair, Jr., and David Richmond went up to the counter and asked for cups of coffee. “We don’t serve Negroes here,” the white waitress behind the counter said. “Negroes eat at the other end.” The four men stayed, even as the manager told them to leave. The Greensboro Four, as they were called, stayed until the place closed for the night. The next day, 20 Blacks came to sit in the Woolworths. The day after that, 60. The next day, over 400 came. The inspiration behind their sit-in protests came from the same comic book that Watkins and Elmer carried.

A young Black man was in Nashville, Tennessee. The student activist was a teenager, preparing for the Freedom Rides, lunch counter sit-ins, and other non-violent protests against racism, the Jim Crow South, and injustice. It was 1958 and the young man read a comic book that would ignite and inspire him. It would do so for the rest of that young man’s life. The young man was John Lewis, who would later go on to speak at the Lincoln Memorial during the 1963 March on Washington and would march side-by-side with Martin Luther King, Jr. on a long walk from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama.

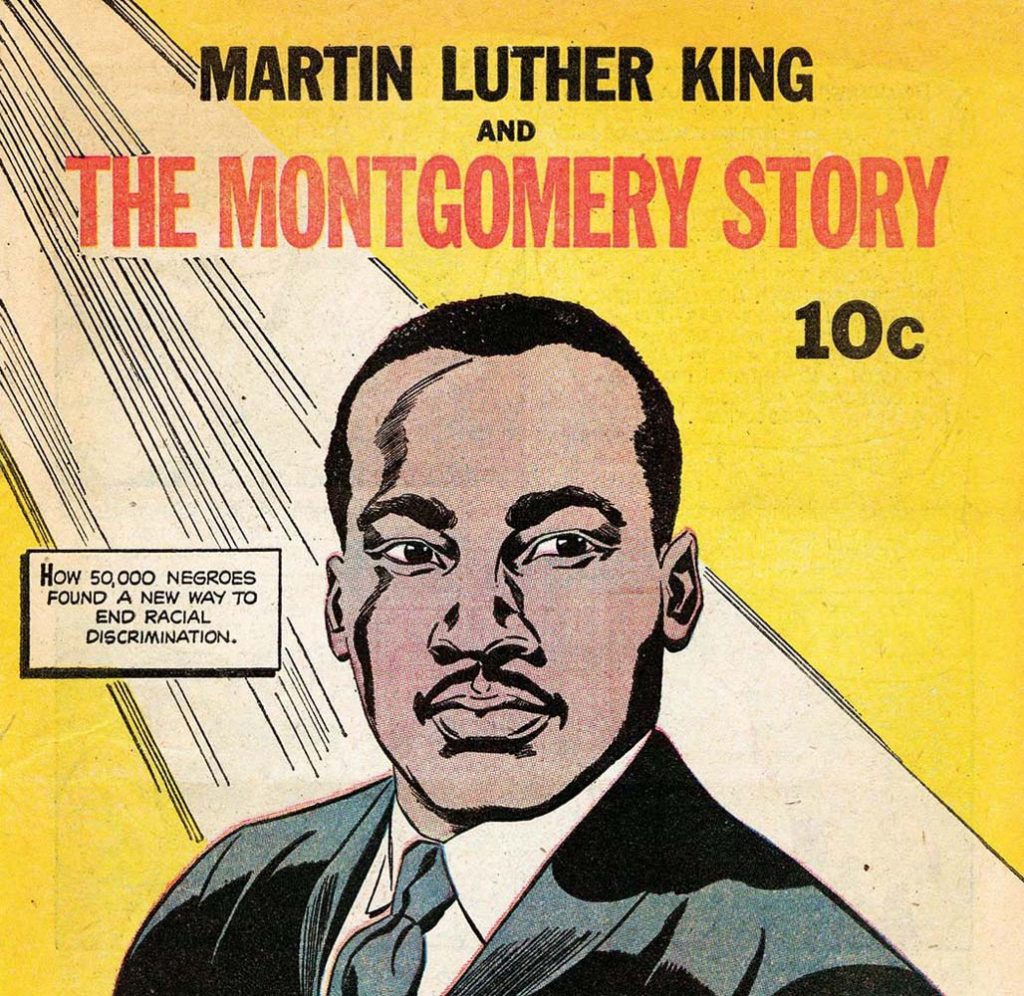

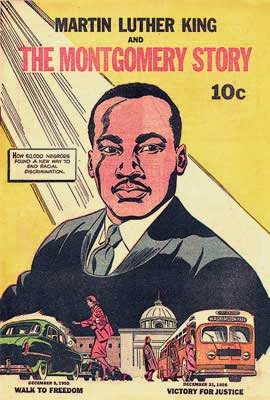

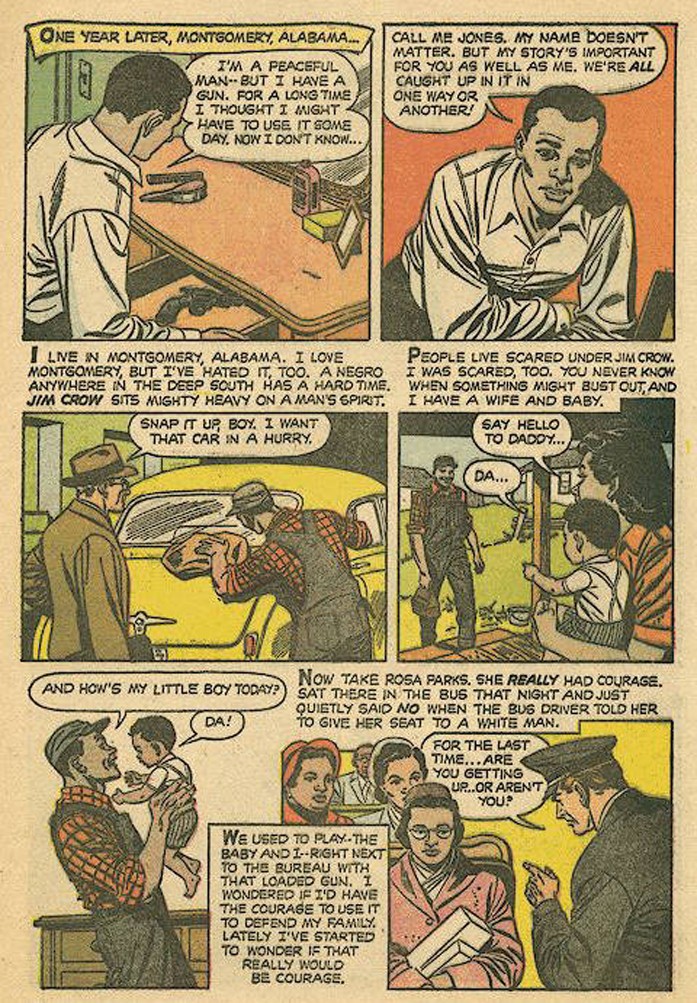

Some comic book heroes don’t wear capes. Some comic book heroes are middle-aged seamstresses (Rosa Parks) and up-and-coming pastors (Martin Luther King, Jr.). Printed in 1957, the comic all those Civil Rights activists were carrying and inspired by was Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story, published by the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR). It tells the story of the Montgomery Bus Boycott, an initiative that propelled both Parks and King into the national spotlight. Moreover, the comic book was a guide for activists in the Civil Rights Movement and beyond on how to stage non-violent protests.

“Arguably,” notes Cole Manley, author of The Unlikely World of the Montgomery Bus Boycotts, recently published by NewSouth Books, “the comic had a greater impact on social movements beyond the United States and the Civil Rights Movement.” During the late 1950s and into the 1960s, the Fellowship of Reconciliation distributed the comic book to anti-apartheid organizations in South Africa. Manley says, “Young church leaders were inspired by Dr. King’s example.” In the first several years of publication, the book was translated into Spanish. “It was sent to Latin America,” says current Fellowship of Reconciliation Director of Communications, Ethan Vesely-Flad, “lifting up Martin Luther King’s message there.” The comic book has now been translated into many languages. “A young Egyptian human rights activist came across the comic book,” Vesely-Flad says, “and discovered it was a great tool.” The activist, Dalia Ziada, took it upon herself to translate the comic book into Arabic and handed it out at the height of the Arab Spring, right there during 2011’s protests in Cairo’s Tahrir Square. “The global dispersion of this comic book,” Manley says, “surely surprises even the most optimistic.” Indeed, the comic book has now been dispensed the world over with hundreds of thousands of copies now printed and distributed.

But every comic book has an origin story. This is its:

Following the success of the bus boycott, which the Fellowship of Reconciliation helped organize, Alfred Hassler, FOR’s Executive Secretary and Director of Publications, with Reverend Glenn Smiley, a friend of Martin Luther King, came up with the idea of a comic book about the boycott. “A comic book is an efficient and effective way to get King’s message to people,” notes Andrew Aydin, who wrote his master’s thesis on the comic book and was Congressman John Lewis’ Press Secretary for a time, and who was instrumental in John Lewis’ award-winning graphic novel series March. “It’s easy to digest,” he says. “It’s easy to understand. It paints a vivid picture. You can put it in your backpack and take it with you.” Something John Lewis did. “If one person had a copy, ten people read it.”

The initial run was 250,000 copies. Martin Luther King, himself, helped edit the book. The artwork was done by Sy Barry, best known as the artist for The Phantom, a job he held for more than 30 years.

Instead of being distributed like many comics of that era were (newsstands, candy stores, pharmacies, etc), FOR distributed them to civil rights groups, churches, and schools, predominantly in the South. FOR staff members brought oodles of comic books with them wherever they went. Every talk they had, every workshop they attended, they’d pass out the comic book after.

“We should speak up and speak out,” Aydin says about the comic book’s message and how it continues to reverberate today. Aydin is currently working on other social justice works, through Good Trouble Productions. “There is a nine word problem with studying the Civil Rights Movement today,” he says. “Rosa Parks. Martin Luther King. I Have a Dream. Those are the nine words most people know about the Civil Rights Movement. These stories will be swept under the rug unless they’re told. Unless we tell them. We don’t want to slip back to those dark days.”

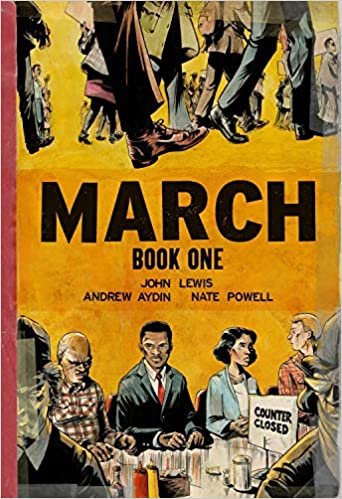

That’s why Aydin helped convince Congressman Lewis to tell his story through the graphic novel series, March. Written by Lewis and Aylin, with illustrations and lettering done by Eisner Award-winner Nate Powell, the first volume was published in 2013 and was the first graphic novel to win a Robert F. Kennedy Book Award. The second volume, published in 2015, was awarded the Eisner Award for Best Reality-Based Work. The third volume, published in 2016, won the National Book Award for Young People’s Literature.

The March series was directly born out of a ten cent 16-page comic book, published by the oldest interfaith peace and justice organization in the United States, in the Jim Crow South decades ago. “It is an example,” Manley says, “of the transactional nature of freedom struggles.” The comic book’s creator, Alfred Hassler, could have never anticipated the comic book’s reach. “This comic book,” Vesely-Flad says, “is the legacy of his life.”

For Aydin, the comic and Lewis’ graphic novels need to be read, studied, and used by as many people as possible. “Young people need to know their true power. That they can change the world and that they can do it through non-violence.” Perhaps there is a kid in Cleveland, or Kalamazoo, or Kiev, or Caracas with March in their backpack and thoughts of a better world in their head. There’s no telling what a comic book can do.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply