Equipped with nothing save a full-body-covering suit, a pair of binoculars, and some type of souped-up motorcycle, a nameless observer from parts unknown has been dispatched by forces just as unknown to survey a hyper-dimensional realm that isn’t just unknown, it may well be flat-out unknowable. Sounds mysterious, right? Maybe even doubly, triply mysterious — so why does Philadelphia cartoonist Pat Aulisio’s latest full-length work, Grid Observer (Clown Kisses Press, 2020, compiled from single installments originally made available on Aulisio’s Patreon), make so damn much sense?

It’s a question I’ve been puzzling over after several perusals of this appealingly “lo-fi,” black and white, offset-printed publication, and the only conclusion I’ve been able to come to is that for a very specific readership tuned in to an equally specific wavelength, this book represents the culmination of a vast and creatively-rich body of work that goes back decades — and much of that work isn’t even Aulisio’s own. I’d trace it back to Jack Kirby to start with, this whole notion of a cosmic “adjacent reality” just outside our own, an idea he debuted with the “Negative Zone” in the pages of Fantastic Four and subsequently followed up on with the “Wild Area” of Superman’s Pal, Jimmy Olsen before taking it to its conceptual apex with “Quadrant X” in Captain Victory And The Galactic Rangers, and after that it was Will Cardini who really picked the ball up and ran with it, elevating and/or reducing it (depending on your point of view) to levels approaching pure abstraction with the various and sundry comics he’s produced set in the realm of his far-out “Hyperverse.” In fact, it could be fairly argued that Grid Observer shares more in common, aesthetically and thematically, with Cardini’s work than it does Aulisio’s own previous efforts, even the unfettered id-transmissions of his Bowman and Survive 300,000,000 comics.

To be perfectly honest, though, I don’t care who’s conjuring this stuff up, or how much one person may be directly borrowing/homaging another, as long as it keeps on coming. The cynical may be tempted to dismiss the premise for having one overt hat-tip to Tron too many, but there’s literally nothing that you can’t do with a parallel dimension/”pocket universe” such as Aulisio’s titular Grid. By deliberately minimizing the import of how his protagonist came to be there and what he’s supposed to be doing to a simple “just checking things out,” he’s free to go about the business of fully exploiting a conceptual framework where laws of time, gravity, physics, and the like just plain don’t apply. In the words of Jim Morrison: “Get here and we’ll do the rest.”

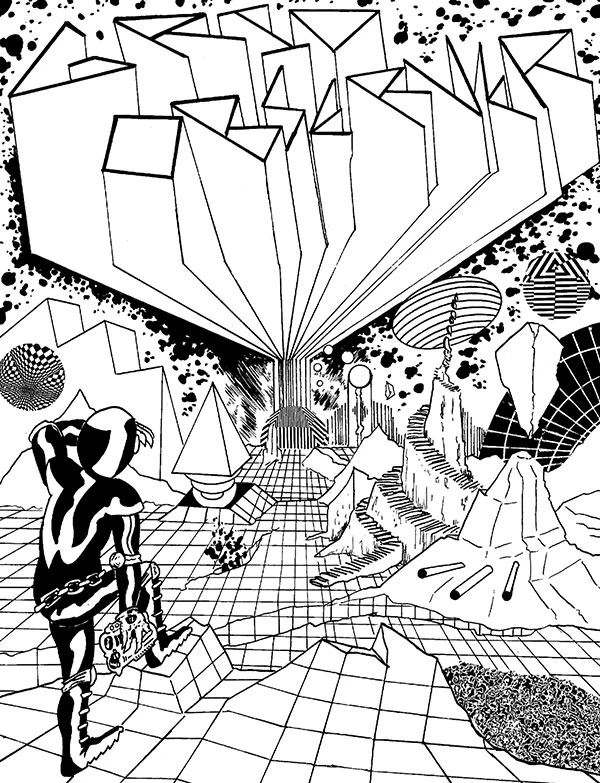

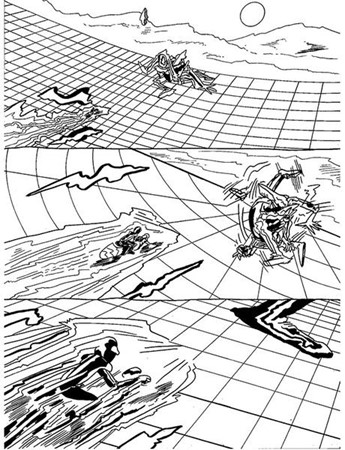

Now, while it’s a known fact that the act of observation changes both the observer and the observed, it’s also a known fact that if all we as readers were doing was observing some guy who was, in turn, observing a bunch of wild and crazy shit himself, it wouldn’t make for much more than an interesting exercise in philosophical navel-gazing, perhaps with the added twist of wondering whose navel it was we were gazing at. Aulisio is many things, but boring has never been one of them, and so he more or less dispenses with the pleasantries right out of the gate as his strange environment begins reacting to the purportedly passive interloper in its midst in breathtakingly unpredictable ways. Dopplegangers, wormholes, floating pyramids, vaguely digitized M.C. Escher staircases upon staircases leading back into/unto themselves, hostile natives made (I think, at any rate) of organic rock, cracks and chasms in the Grid’s foundation (which is, of course, a grid itself) — it’s all here, and it all follows a pretty basic linear trajectory, even in Aulisio’s wonderfully recursive double-page spreads. Admittedly, he’s every bit as trapped as his protagonist in that he’s consistently having to visually one-up himself, but he’s always more than up for the challenge — in fact, things get even more interesting when our ostensible “hero” loses his bike and has to continue his observations (which invariably escalate to explorations, which, then, invariably escalate to conflicts) on foot. Still, once you’ve seen, interacted with, and fought against creatures and environments that defy both explanation and the ability of logic to adequately process, how can you really top that?

Well, I guess you could always die — and, spoiler alert, our observer does manage to do that. As you’d no doubt expect, though, the grave isn’t any more permanent than anything else in this realm, but hey — once resurrected (with the aid of a necromancer who may be friendly or may just be doing his job), there is something akin to a moment’s peace, as well as some answers, to be found when the observer actually manages to get one of the locals to engage in a little bit of terse conversation. Ironically, though, we learn more about him than we do about either the Grid itself or his less-than-chatty companion.

Where is the Observer from? The void. What does he do there? Nothing. How does he like it? Hey, it’s not so bad. How’s he going to get back? As the book closes, it really doesn’t seem like he ever will — but it also doesn’t seem like it matters. He’s come a long way, no doubt about that — he’s pierced the veil between dimensions and even pierced the veil between life and death — but he’s still come up empty-handed. That may lead one to reasonably conclude this whole exercise has been a waste, sure, but when you consider that he wasn’t sent to get anything anyway, and, literally, he has nowhere to go back to, then what else can you say other than “mission accomplished”? The Observer has made it to the mountaintop — and, as readers, we’ve reached the end of a journey that, at least by this critic’s calculation, goes all the way back to F.F. #51 in 1966 — only to find there’s nothing much happening here, either.

Was it the quest itself that mattered, then? Probably not, seeing as how it never had any real objective in the first place. And there were no particular “friends made along the way” or anything of the sort. But maybe that’s not even the right question to be asking when you come to the nearest thing one can imagine to the end of the universe and hit a brick wall. When you depart from one nowhere and arrive at another nowhere, maybe the only question that remains is: are you ready to turn around and do it all over again?

If Pat Aulisio is my tour guide on this infinite feedback loop, then my one-word answer is: absolutely.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply