Publisher’s Note: Karl C. Krumpholz is a regular contributor to SOLRAD with his LIGHTHOUSE IN THE CITY series.

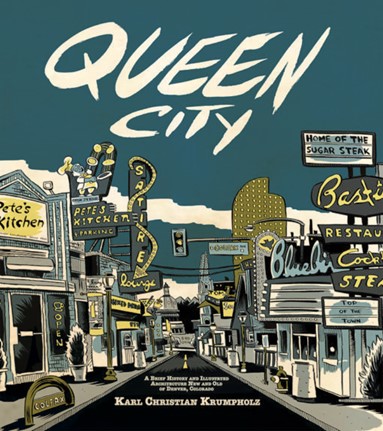

At first glance, it’s tempting to go for the easy label and classify Karl Christian Krumpholz’ ambitious new project, Queen City (Tinto Press, 2021) as a “love letter” to his adopted hometown of Denver — certainly the book’s subtitle, “A Brief History And Illustrated Architecture New And Old Of Denver, Colorado” would do nothing to disabuse a person of this notion — but that would be far too reductive on the one hand, while rather missing the point entirely on the other. In reality, what we have here is something infinitely more nuanced but, perhaps paradoxically, much more straightforward than a heartfelt paean: what Krumpholz has created is, at least in this critic’s view, better described as a visual history that goes right up to the present day.

It’s also a culmination of sorts of a particular phase of his cartooning career, one where the city itself is every bit as much a living, breathing character as, well, his characters are, and while it’s technically accurate to point out that Krumpholz is, in fact, an East Coast transplant, I don’t think there’s much doubt that if Denver were to name a “cartoonist laureate” (don’t laugh, Vermont does it), he’d be the guy. And yet, his work seems forever to be imbued with the sense of curiosity bordering on wonder that generally only comes from an outsider looking in, and boasts none of the tonal hallmarks of someone burdened with dyed-in-the-wool familiarity. I mean, I could tell you everything you’d ever want to know and then some about my south Minneapolis neighborhood (I should hope so, having lived there for 22 years), but it doesn’t mean I would find the prospect of doing so either interesting or appealing. It’s all old hat to me. Krumpholz, by contrast, appears to have taken a view early on after relocating to the Mile High City that it was an enigma to be investigated, explored, perhaps even prodded at, and that insatiable curiosity, which has served him in good stead for many years now, is absolutely essential for this very nearly academic text to be successful.

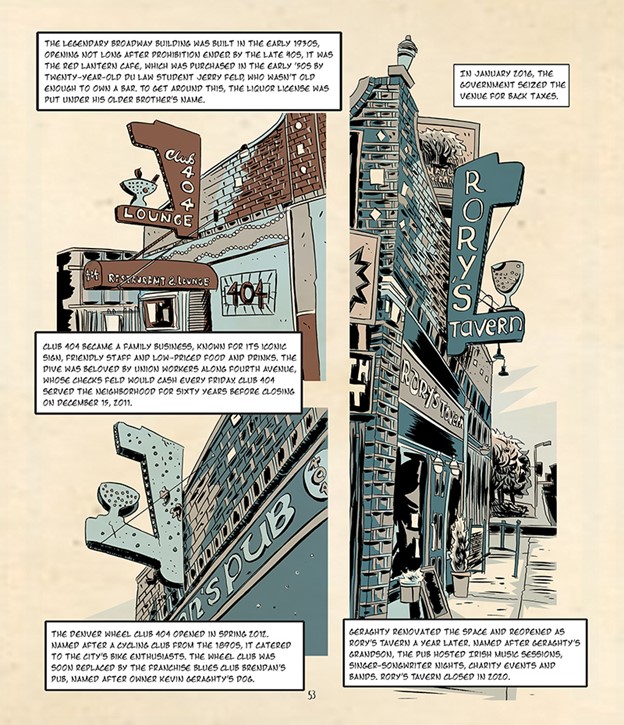

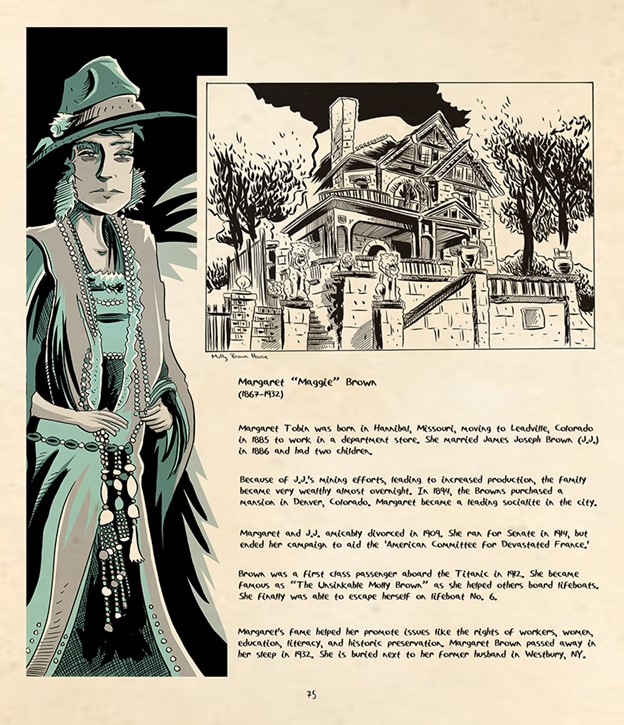

Mind you, when I say “very nearly” academic, I don’t mean to slight the research Krumpholz has put into this volume, which was obviously quite exhaustive. What he doesn’t do, though, is adopt the dry and detached view that’s common (and not without good reason) to so much of academia. The cartoonist is clearly invested in the people, events, and, perhaps above all, the buildings and structures that have both made Denver what it is, and what may or may not be a part of its future. But his is not the deeply personal investment of someone who literally grew up seeing movies at a particular theater or who drank away their twenties at a favorite watering hole, although bars and taverns are clearly one of his favorite things to write and draw about, as well as spend time in. What Krumpholz is invested in is the not-always-cohesive story of Denver — as a city, as a collection of neighbors and neighborhoods, businesses and business and business districts — and its various and sundry changes, its cycles of booms and busts, are not just “part” of that story, in a very real sense they are the story.

So, yes, a “story” this is — but a cut-and-dried “graphic novel” it isn’t. Krumpholz’ approach to his subject matter is innovative, but again it should be stressed that it borders on the academic, so don’t expect a straight narrative throughline. Instead, be prepared for a collection of thoroughly absorbing vignettes about the people, places, and things that make up the metaphorical individual ingredients of Denver’s equally metaphorical stew, accompanied by impeccable illustrations that capture their essential character and feel every bit as much as they do their bricks and mortar, eyes and hair. Many of these pieces originally ran as singular installments in the Westword “alternative” newsweekly, but while the project began life as a collected volume of said work, the COVID-19 pandemic engendered a rather ambitious expansion of Krumpholz’s initial remit, as he took it upon himself to pay special attention to any number of places that he was fairly certain wouldn’t emerge as going concerns on the other end of it. And yet —

“nostalgia tour” this is not, either. As Denver, like a depressingly large number of other cities, becomes thoroughly homogenized thanks to chain businesses and overpriced, lifeless condo developments, Krumpholz’s aim is more along the lines of recording the past than it is preserving it. Again, this approach likely comes far more naturally to an outsider than to one born and bred, even an outsider who’s been in a place for some time, as is the case here, but it doesn’t mean that Krumpholz is any less in love with his city, particularly the small handful of neighborhoods that he spends the bulk of this book examining, than someone who’s always called the place home. It simply means that his love is borne of what very well appears to be an insatiable sense of curiosity about the city, as opposed to any particular sense of hometown loyalty.

Still, you know what they say, no one has more sincere convictions than a convert, and Krumpholz’s sincerity, combined with his frankly stunning artwork and Tinto’s admirably high production values, combine to produce a living, breathing historical document that celebrates the rich uniqueness of Denver, warts and all. Indeed, one can see why a certain “carpetbagger” from Eastern parts was so enamored with the city in the first place, and why he continues to be so — which brings to mind another old but accurate cliche: home is where you make it.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply