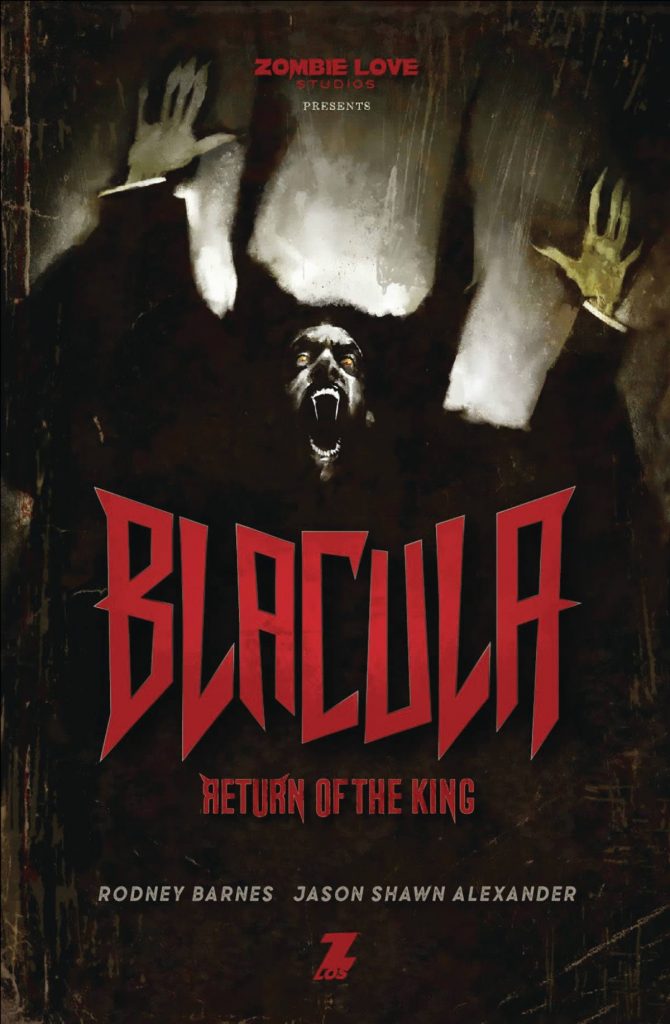

When Blacula sank its fangs into moviegoers in 1972 it was an idea whose time had come, the first black vampire. Between director, William Cain, and the magnetic presence of the film’s lead, William Marshall – “that is one strange dude,” as 70’s club kid Skillet says, “that’s a baaaaaaadddd cape,” – black audiences were given the (dark) gift mostly white readers received when Bram Stoker let loose his literary creation on unsuspecting Victorians: agency, the ability to do anything, anywhere, all at once. The primordial potency of the vampire as a metaphor, symbol, and folkloric myth provides an abiding action and indefatigable intervention because it is both pure imagination and boundless possibility.

Half a century after Crain and Marshall unleashed their horror on moviegoers, writer Roddy Barnes through his Zombie Love Studios, along with his Killadelphia compatriot artist Jason Shawn Alexander bring forth Blacula: Return of the King, an iteration whose time is long overdue. The trades may categorize it as a “graphic novel,” but this is pure comic book battiness. Pulp at its pulpiest. Barnes and Alexander pay fealty, of course, to the source material while also providing equal homage to the accumulated vampire lore since. It’s clear from the text, Barnes has watched and read a lot of vampire movies and books. What he expands on is the “generational trauma” of Blacula and, one could argue, all of the vampire genre. The term “generational trauma” was coined in 1966 by a Canadian psychiatrist in regards to Holocaust survivors before being expanded to any survivors of generational trauma. On a much lighter note, Barnes also knows comics and imbues Blacula: Return of the King with another more modern dark knight and another inexhaustible IP with similarly vampiric tendencies in popular culture, Frank Miller’s Batman: The Dark Knight Returns. No fictional character nowadays is better defined by his trauma more than Batman. Barnes and Alexander sprinkle DKR DNA in their tale with that always-engaging schoolyard speculation of who could beat up who. To his credit, Barnes knows he’s writing a comic book and not a master’s thesis.

For those nervous nellies or purists who feel ill at ease in their lack of knowledge in regard to the source material, fear not! Barnes is a stone-cold yarn spinner and, so, he catches up the innocent by judiciously picking over the bones of Blacula’s origin as set down in celluloid fifty years ago. Blacula is also currently streaming on Prime Video, so there’s that. The prime-A-1-iykyk fact about Blacula is that Blacula is not this vampire’s name; Prince Mamuwalde, if you please. In perhaps a cognizant show of support for 70’s black culture and leaning into the blaxploitation genre, screenwriters Joan Torres, Raymond Koenig, and Richard Glouner penned the name Mamuwalde for their black vampire progenitor. “Blacula” is actually a curse put on Mamuwalde by none other than Dracula. As Barnes and Alexander recount in a black-and-white flashback, Mamuwalde — charged by his Ibani tribal elders — travels to Transylvania to politely ask the Count Dracula to divest his holdings in the slave trade. As scholar Dr. Robin Means-Coleman says, “Blacula” serves as both a curse and Mamuwalde’s slave name, hoisted upon him by his white master, Dracula. Heady stuff for a low-budget popcorn movie to be similarly in the pocket of a 70’s Afrocentric point of view and far ahead of its time in terms of cultural politics. If Mamuwalde is ever going to gain his manumission, even if he will never be free from his condition, then he’s got to take down his (white) master.

Mamuwalde is bitten by Dracula as punishment for not allowing the Count to, in the parlance of our times, fuck Mamuwalde’s wife, Luva. To add insult to eternal injury, Mamuwalde must live out his days without Luva when she is left to die while he is locked in a casket to starve. How Mamuwalde gets from a crypt hidden in Castle Dracula to South Central L.A. is too much of a hoot to spoil but makes (more?) sense in today’s world in which HGTV is a thing than it did in 1973. Sadly, perhaps, Barnes dismisses this bit of Blacula lore because this is a revenge story and not a referendum on home designers and cultural appropriation.

Much of the film concerns Mamuwalde’s attempts to woo Tina (Vonetta McGee). Several scenes have them meet up at a hip L.A. night spot where folks groove to the sounds of the house band, 70’s pop and soul trio, the Hues Corporation, who provide the backbeat for their assignations. Mamuwalde believes Tina is the reincarnation of Luva; (black) love never dies. Mamuwalde does, however; immolating himself instead of being killed or captured by the police.

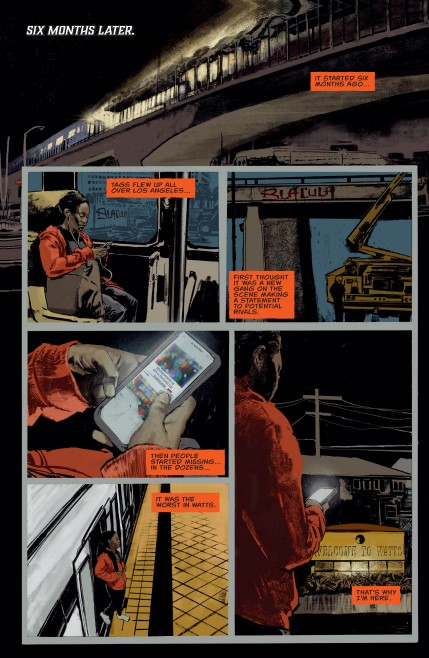

Those familiar with the literary Dracula will recall that it is an epistolary novel. Blacula: The Return of the King offers a modern-day correspondent in Tina Thomas, a blogger (and one may assume podcaster, even though it’s not stated, but c’mon!) for “Dark Knights, a blog that chronicles all things unnatural, uneasy, and undead in the greater Los Angeles area.” On the one hand, the Thomas character feels fresh, an ingenious play on the epistolary nature of Stoker’s novel — the name of her blog nodding at Miller’s magnum opus notwithstanding — on the other hand, it also feels trite which, perhaps, making her a podcaster would have been even more hackneyed. Good on Barnes for not creating one-for-one comps for Blacula or Dracula. And yet the influence of Thomas’s blog, the blog itself, and her bonafides as a journalist or amateur sleuth are left to the reader’s imagination. This lack of information speaks, perhaps, to the story’s pulpiness and Barnes’s choice to choose contemporary cultural signifiers to shortcut more in-depth character development.

As “Blacula” tags go up all over greater Los Angeles and the bodies start disappearing from black communities like Watts, our intrepid blogger begins to investigate. Immediately after Thomas’s introduction, Barnes and Alexander pull from their Killadelphia playbook and bring in a heavy, maybe the heaviest, Mister it’s-better-to-reign-in-Hell-than-serve-in-heav’n himself, Satan. Alexander, having cut his teeth with other devilish denizens of Hell in Spawn, draws a great Satan. His Lucifer has the Tim-Curry-as-Darkness horns and a long full, pointy, and yet scraggly beard – a beardy-bro of hirsute hellspawn. To explain “how the devil,” the Devil shows up here, Barnes imagines that when Mamuwalde killed himself, his body turned to ash, but his soul went south. As John Entwhistle once wrote, “And down in the ground / Is a place where you go / If you’ve been a bad boy / If you’ve been a bad boy.” Mamuwalde has been chillin’ over the decades in hell and (apparently) occasionally petitioning the Devil for his release so he can take revenge on the one who turned him into a vampire, Dracula. After another failed plea sesh with Satan doesn’t go his way, Mamuwalde says ‘fuck it’ and does it himself. And thus, the “return” of the title. Sans therapy, if one is going to right the wrongs of generational trauma then look within and if you happen to be a supernatural being with fangs all the better.

This “king” has not returned to reclaim a title, no, he’s out for revenge, plain and simple. Mamuwalde has the flash and fashion sense of the most vain vampire, but without a Guillermo to clean up afterwards, he’s shit at dealing with the bodies of his victims, almost all of whom become vampires. As much as Mamuwalde wants to kill his maker and slake his thirst for revenge he can’t help, but ‘cause trauma himself.

Which brings us back to Thomas and her “investigation.” While on the prowl for Blacula, she encounters Kross, a kind of Wallace-from-the-Wire pseudo-father to the many orphans – the (grand)sons of the batman, if you will — Mamuwalde has created in his thirst for blood and vengeance. Among these children is Bop, a young boy whose mother and sister were turned into vampires (it’s unclear if it’s Mamuwalde’s doing) who often visit him ‘Salem’s Lot style by floating outside his bedroom window at night. Cutting Bop out from the bunch and giving him a backstory indicates Barnes’s intention to show how generational trauma comes from different sources even as it extends through generations.

The hints and allegations of Blacula née Mamuwalde’s return have made their way to his master’s ears and so Barnes and Alexander (re)introduce another baddie only seen, so far, in flashback, Count Dracula. His arrival at an all-night diner is a little too on the nose, but again Barnes can be excused for the sake of fun. Dracula befriends a waitress who makes a terrible decision to drive him home to her doublewide in Lancaster in Northern Los Angeles County. Not quite the square footage of his European digs, but once he does away with her he has a headquarters to work out of that’s spitting distance from LA proper.

If you’re going to drop a vampire into LA then sooner or later the cops are going to show up. On that score, Barnes, like the director of Blacula, William Crain, de-fangs the police. Where Crain made them inept buffoons who couldn’t shoot straight or properly file paperwork, Barnes takes his ineffective coppers from a dusty Deputy’s office to the street. After Mamuwalde eviscerates a bunch of gang members, the cops investigate and roll up with sirens blaring and guns drawn. The thin blue line quickly runs red as Mamuwalde makes short work of the boys and girls in blue who tell him, “to stop resisting” as he has his hands raised. Regardless of the reader’s take on policing in America, Barnes offers nothing to the conversation or setting except bloodlust. But what should one expect? Don’t draw down on a vampire. Period. Whereas Alexander is artful in showing how Mamuwalde dispatches the gang members and separates limbs from torsos with wide swathes of red and fangs hidden by necks and such, the cops get no artistic discretion. Pulpy though it may be, these cops are red shirts (literally and figuratively) who happened to have pulled up on the wrong “unarmed” dude in a cape. Barnes knows and wants to reinforce the point that Mamuwalde is a killer and he kills indiscriminately, be it cop, criminal, or innocent.

Like the forlorn, put-upon, and moody bloodsuckers of Anne Rice and Charlene Harris’s work, Mamuwalde, post-massacre, retreats to an abandoned house to reflect on his life choices. He gets existential about leaving hell and returning topside. “Maybe Satan knew best,” he says before remembering his life in Africa overseeing “rites of passage ceremonies.” He wonders if he is guilty of being like an “angry child that cannot see past his trauma.” A vampire kills to live, his agency and his life extends or continues the trauma from which he suffers as well, this is why the concept of the black vampire that Marshall, Crain and Blacula’s trio of screenwriters hit upon half-a-century ago continues to have so much resonance, not only does it allow for representation, but it brings a different cultural dynamic to an idea that has been, if you’ll pardon the pun, bled out from so many one-dimensional retellings. Make Dracula black and you’ve got a new set of problems to deal with. Blacula matters. Reverie over, Alexander draws a close up of Mamuwalde’s eyes with the words “Dracula must die” perched in a text box, courtesy of letterer Marshall Dillon, between his prominent brows which reignites the revenge plot.

When Mamuwalde and Dracula finally face off with fangs and fingernails drawn, their fight does not disappoint. Alexander’s painted art goes for the throat, chest, arms, legs, and everything in between. The turnout and cape, especially, that Alexander draws for Dracula for this showdown has to be seen to be believed. As a mixed media master, Alexander brings layers to this fight that classic cartooning alone perhaps couldn’t capture in all its red dead revenge. Bop says it best, “this is better than wrestling.” Unlike the Batman v. Superman battle royale that ends the Dark Knight Returns, Mamuwalde walks away, still undead, but alive. So, I suppose since he lives, he’s Superman in this scenario, I guess? The same cannot be said for the O.G. “Batman,” Count Dracula, whose soul ends up in hell. After a short palaver with the Devil, he learns what the Prince of Darkness has in store for Mamuwalde. Pro tip: Don’t fuck with Satan.As the ouroboros of fandom fueled by reboots, remakes, and reimaginings continues to inform so much of today’s entertainment culture, it would be easy to dismiss Blacula: Return of the King as cynical, scraping the bottom of the IP barrel. Blacula may have been relegated to cinema’s dustbin, but, for many, its cultural impact continues to reverberate in scholarship about blaxploitation and film history. To further this discussion, Barnes includes the self-penned introduction, “Blacula and Me” and an essay by Stephen R. Bissette, “Prince Mamuwalde Lives!” in Blacula: Return of the King. As a writer for the animated adaptation of The Boondocks, Barnes knows how to deliver social commentary while staying true to what brought people in the door to start. Representation is important, sure, but it’s gotta be fun to boot. The revenge plot gives him a skeleton to hang his story on and possibly the one plot older than the vampire tale. As referenced earlier, vampire writers like Rice and later Harris made a mint mining trauma out of hunky vampire mopes. Which is why, perhaps, Barnes turns to the first revenge seeker, Satan. Putting the Ur-revenger in your vampire story provides dimension and a supernatural and biblical balance to the bloodlust. By their nature vampires are border-crossers in every way, shape, and form which is why their kind knows no bounds, narrative or otherwise i. e. Agency. Like Crain, Barnes knows a vampire’s agency transcends race to go deeper into culture to provide meaning. Blacula: Return of the King proves a good idea, like the vampire, like revenge, never dies nor goes away … for long.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply