It’s an odd thing, family, in a way it will take you quite some time to really realize, let alone articulate. These are the people you are born into, the contexts you are born into; by the time you come to recognize them as such they will have already grown rigid. Sometimes, if you’re lucky, you’ll have more common ground with them than the purely circumstantial, or, at least, you will have enough overlap to avoid friction; if you’re not as lucky, though, you’ll grow to notice the divergences as they widen in real time, you’ll watch common languages splinter into warring dialects that want nothing to do with one another in spite of shared roots, leaving only gulfs of a grief that’s hard to articulate or pin down at all; the people will still be there, yet what they meant—what you thought they meant—will have completely changed in your eyes.

Sledgehammer, Sam Alden’s digital graphic novel released at the end of 2022 for a price of its readers’ choosing, is preoccupied with that latter scenario. Set in a near future, it tells the story of animator and director Darya and her mother Vera, and their struggles to connect with each other. But the mother and daughter are rarely present in the flesh: most of the comic focuses on the production of Darya’s latest movie, one in a long line of attempts to represent her fraught relationship with her mother. The way this one differs from the previous ones, however, is that the previous ones—which the reader is only exposed to from their recreations within this new movie—all attempt this representation through a thin veil of allegory, whereas this new effort changes none of the names, none of the surroundings.

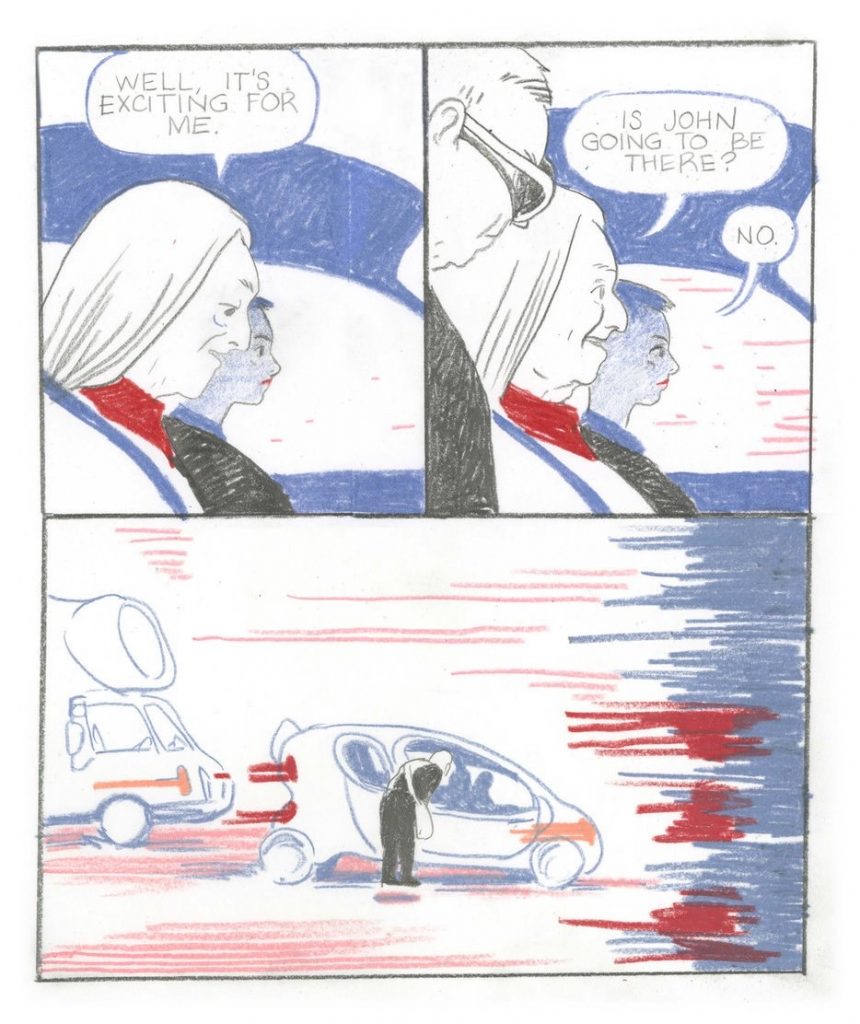

Alden constructs his story with a meticulous form of intimacy. Its pages are sparse, never sporting more than four panels of approximately similar sizes (always set on two tiers of equal height); the art within is all drawn in pencil and colored pencil, without much at all in the way of rendering—shapes are either filled in completely or not at all. The spaces, too, are sparsely populated—Alden is more likely to fill in backgrounds with blocks of solid color, or else to simply keep to a blank white, than to depict much in the way of furniture or set-pieces when such is not completely necessary. This allows the story to revel in a level of immediacy that could very easily be transferred to a theatre stage.

If anything, even though Sledgehammer is about animated movies, the artform it evokes isn’t film but theatre. On a purely sensory level, the theatre is the epitome of the hyperreal: you occupy the same space as the actors, you see and hear them without a screen as mediator; you are perpetually reminded of their tangibility, of their tactility—both facets that exist only to undermine themselves on the strength of their inherent fiction. It’s this level of deceptive immediacy, this interplay of presence, presentation, and representation, that Sledgehammer aims for—and to a great degree achieves.

By hinging the production of Darya’s movie on advanced motion-capture technology and computer-generated sets, Alden adds a visually tangible level to his nesting of emotional proxies: Darya, now a middle-aged woman and a well-known director, is frequently seen standing on the stage while her two actresses play out their scenes; the movie moves forward through Darya and Vera’s lives while the two actresses stay the same, and all the while Darya simply stands there, blinking in and out of the frame as its planes of reality collapse in on themselves and all that remains is Darya, perpetually the spectator.

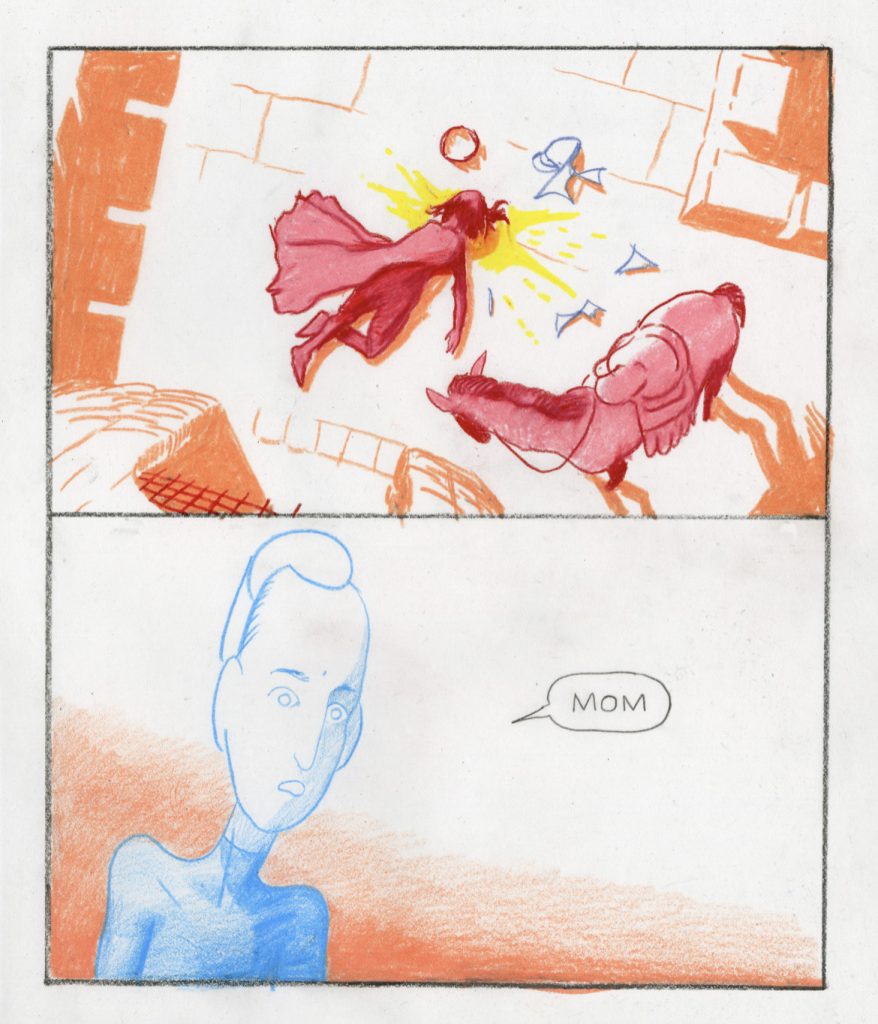

In one of those scenes, Darya explains to her mother the function of her latest movie, another one of those barely-allegories in which a daughter behaves recklessly and actively makes her mother’s life difficult. “I always try and portray myself as worse than you.. it’s all meant as an apology,” she says, to which Vera replies “Well, I don’t really want to watch that over and over.” Alden is not particularly subtle with what he wants to say: proxies and projection get you nowhere, no matter how immersive you manage to make them—by attempting to reflect the truth meticulously, all you manage to do is run away from it by propping up your own version of it.

The whole framing of the story, too, points toward this inherent infidelity: Darya purports to empathize with her mother, to humanize her in Darya’s own eyes through her work—yet it’s not until the very last scene that Vera herself actually appears in the story, when Darya comes to visit her and tell her about the new movie. When the two women speak, it’s clear that Vera is not entirely lucid as she trails off mid-conversation, her memory of her daughter coming and going. But this is shown only after the wrap party scene, in which Darya speaks with the actress who plays her in the movie, acting as a proud mother figure, followed by a sequence showing Darya and the two actresses dancing together in the CGI mo-cap suits—displaying them as they “transform” first into Darya as a child then to her original characters, her stand-ins for herself and her mother.

This strikes me as almost a subversion of the zeitgeist’s found family narrative, exchanging the latter’s core thesis of fulfillment and reclamatory comfort for a sincere wistfulness and longing, not for the traditional genetic familial structure but for the sense of fixed, rigid surroundings—Darya’s attempt to melt and slide into the roles of the people around her is a consequence of her robbing herself of her own agency, of her own existence in her world, for years, to the degree of almost total self-annihilation that is only made worse by the fact that it was, in theory, totally preventable.

Under a less-competent hand, the all-encompassing festering resentment of Sledgehammer might feel frustratingly one-note, but Alden’s totality and many-angled approach manages to eschew judgment in favor of visceral empathy for a fundamental human struggle. Darya’s continued efforts to reflect her relationship with her mother do not emerge from selfishness or laziness, nor do they constitute an attempt at escapist solace: they are a cry for help borne of acute alienation, a wish for a guidance that she knows will never come.

For people of a particular makeup—myself included—it is exceedingly easy to get lost inside one’s head, to draw maps of hypotheticals in order to avoid the territory. But in the end, no matter how well-drawn your maps are, they’re just ink and paper, and by the time you come to recognize them, it will be too late; you’ll already be lost. Sam Alden’s Sledgehammer will be there when you come to that point; it offers no easy answers, but it does offer someone to be briefly lost in the same ways with. And sometimes you have to hope that that’s enough for a start.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply