Tolstoy had it wrong. Families aren’t unhappy, they’re weird, downright queer, if you will; all of ‘em, weird and queer in their own unique, odd, and wonderful ways. A Pros and Cons List for Strong Feelings opens with a prologue that captures a small, indelible, and weird detail about growing up in a family: control of the car radio and the social pitfalls therein.

Will Betke-Brunswick applies such idiosyncratic memories to their work as the sugar to cut the strong medicine of interrogating their mother’s cancer diagnosis, treatment, and death. The seven-lane expressway to autobio comics immortality is paved with the sort of quirky preciousness of car radio hegemony as if every cartoonist’s personal experiences engender both Bechdel-ian-warts-and-all-honesty coupled with Pekar-like warts-and-all-detail.

Betke-Brunswick heismans the majority of their fellow autobio cartoonists—all those broken heroes, memoirists all jamming highways on last-chance power drives—with a one-two punch of charm and verve. No family is better or worse (or weirder) than another, some just have better writers.

A Pros and Cons List for Strong Feelings isn’t about cancer or dying, it’s about life, family life, a demonstration that raising children and being a child holds drama enough. And that It’s only in a crisis when the strength of family, formed by mundane everyday experiences like piano lessons, the food kept in the fridge, and the drama over school picture day, etc. proves out.

Betke-Brunswick—referred to in the narrative by various pet names (so many they dedicate a whole page to cataloging them all)—anthropomorphizes their family as penguins in an all-avian world. What keeps the story from not becoming too dear or overtly treacly is that Betke-Brunswick appears to have lived a rather mundane suburban childhood within a caring and loving family. No rare feat, but in a subgenre that embraces the peculiar and the scandalous with equal measure, it’s refreshing. Let he who is without cul-de-sac torpor or suburban ennui cast the first garden gnome!

Betke-Brunswick’s choice to depict their family as penguins offers a filter, a narrative remove, a tool to investigate tough subjects, in this story, the death of a parent, Betke-Brunswick coming out, and day-to-day family life. Over the course of nine months, Betke-Brunswick takes readers through the different stages of their mother’s cancer. Each stop is predictable (diagnosis, treatment, etc.), not because Betke-Brunswick lacks originality or creativity, but because the treatment of end-stage disease is prescriptive, that’s how medicine works. It’s also a memoir of a life and of lives, so however one’s mileage may vary on the topic of palliative care, you’re shopping in the wrong aisle if you’re waiting for an alien invasion, punch-ups, or a deathbed confession. Yes, the sequence when the out-of-town friend’s son sends pot packed in a coffee can from California in hopes of jumpstarting the mom’s appetite plays as de rigueur and somewhat trite in our what-was-once-taboo-is-now-a-legal-high times, but so be it, the vaporizer is a pleasant and thoughtful touch as is the request for a bear claw cookie.

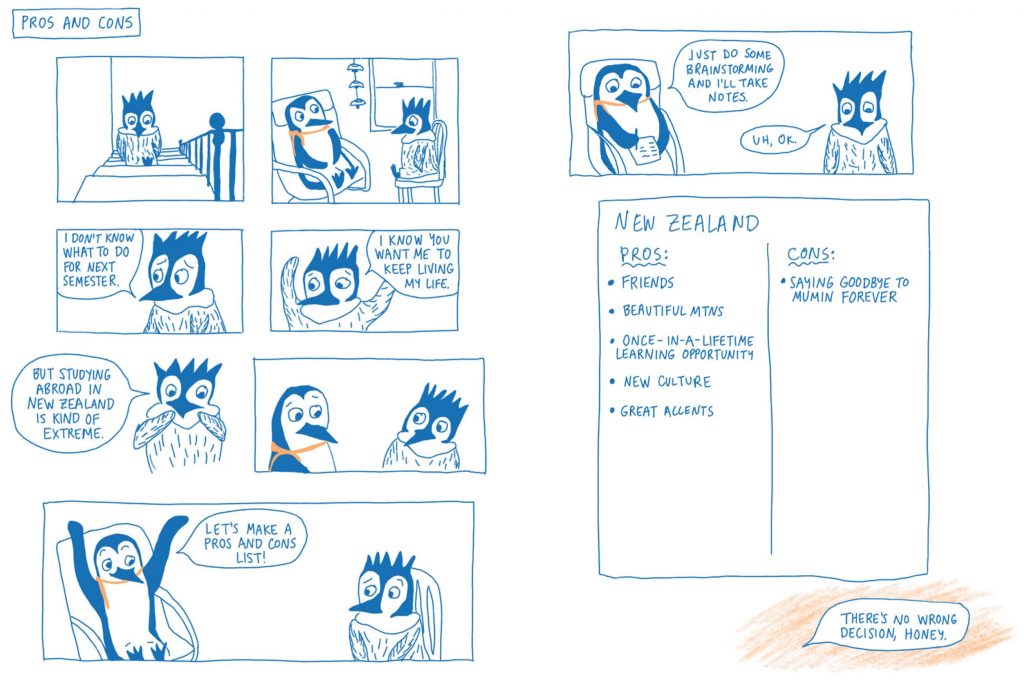

The mother’s diagnosis has a terminus and therefore moves in a straight line, but the narrative obeys no such rule as memories flood reality in that “time is a flat circle” sort of way. As a memoir, A Pros and Cons List for Strong Feelings is precisely that, with the words “strong feelings” as stand-ins for “life.” Death is proof of life. Death only occurs to those who have lived. To borrow from an IP wizard, “we have to decide what to do with the time that is given to us.” Betke-Brunswick decides not to dwell in despair or sadness. Their mother was not her cancer. She lived. She did more and lived longer than the last nine months of her life and that is the story Betke-Brunswick chooses to show.

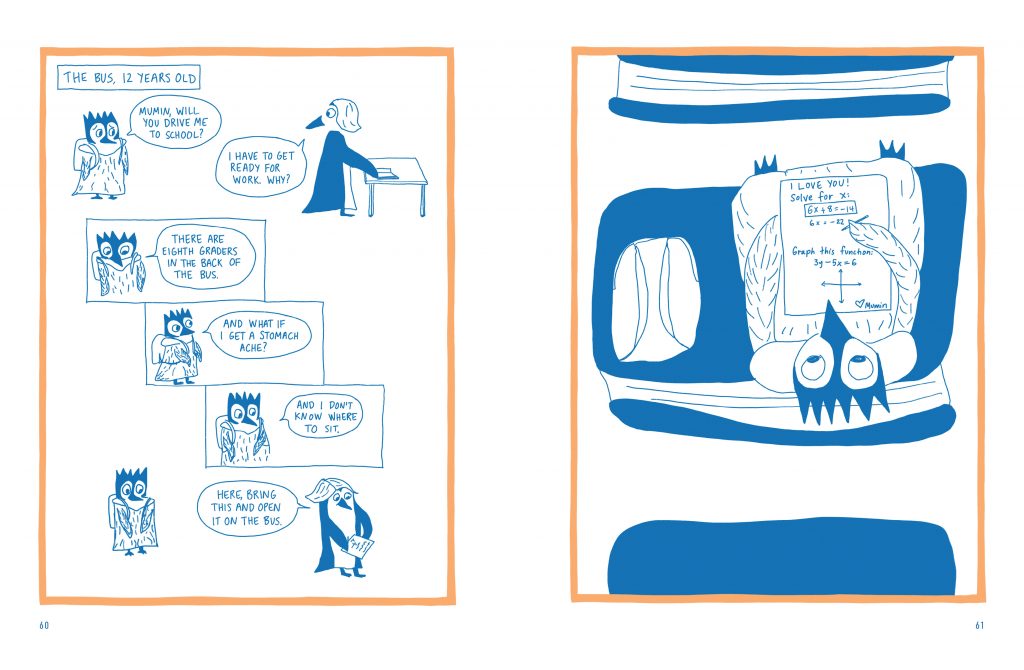

Betke-Brunswick refers to their mother with the sobriquet “Mumin.” Again with the family nicknames! They’re sweet and goofy, but their insider nature chafes. Mumin is a caretaker, a look-maternal-up-in-the-dictionary-and-the-picture-you’ll-see type of woman, who heartily cheered and supported her children prior to her cancer diagnosis and continues to do so, even as she lay dying. Betke-Brunswick’s recall of childhood moments shows that “Mumin” was as quick to send her child off to school with a math equation as a strategy to occupy their time/mind on the school bus as she was to make sure they applied sunscreen whatever the weather, even when ensconced in a costume. “Mumin” was also supportive of Betke-Brunswick’s coming out.

Wrapped up in this “our cancer year” tale is Betke-Brunswick’s experience of self-identifying as genderqueer. When Betke-Brunswick’s penguin avatar asks, “Can I be a boy?” “Mumin’s” reply comes from a place of love and support of affirmative action, “no, the world needs more women engineers.” The dad, PJ, a retired doctor or perhaps psychologist (it’s unclear and perhaps therefore unimportant), doesn’t get it at first and chooses to take a cerebral approach to understanding what their child is trying to express. There’s no big blowup or dramatic disownment, nothing so untoward, instead there is a crossword puzzle that Mumin makes that finally gets PJ to come around. If only it were so easy. If only one had parents like Mumin and PJ? Betke-Brunswick’s ersatz penguin parents are a matched pair, mates for life like their inspiration as supportive with each other as they are with their children. In the course of telling a story about their mother’s death and their coming out, Betke-Brunswick illustrates that life, not death, has no limits, memories and moments always live on.

In a book suffused with emotion and pathos, the section entitled, “Final Family Vacation,” hits hardest because of the inevitability of the heading (the first time Betke-Brunswick chooses to be so exacting). Dying is a process, a series of signposts, and when Mumin and PJ forgo another round of “family fun night” to sit quietly on a dock and watch the sunset, it’s a reminder that families are made up of individuals who relate and resonate with one another at different frequencies. As one matures, one confronts the fact that parents were lovers before they were parents and the loss of a longtime love deserves the space, narratively and emotionally, that Betke-Brunswick offers.

When Mumin dies, it’s a shared experience, a family moment. Dying is shared, death is singular. Everything that happens in the narrative has happened so the family can be there for Mumin at the end. The lived moments that she experienced with her family are what extends beyond this mortal coil. Again, it is life that is limitless, not death. Our love for one another is a reminder that death is only one part of life, love transcends this “final” moment. What a privilege. Credit Betke-Brunswick for creating characters that feel human and doing so with such economy that, by the end, you feel… strongly.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply