1. OVER THE RAINBOW

I’m excited to click on an interview to hear Gilbert Hernandez talk about borders, but it’s just about his panels—those kinds of borders. I’m disappointed, though I suppose they are similar regulatory mechanisms. There is an inside and an outside, the idea of a line. Gilbert’s famous Palomar is always defined against the U.S. border (“below” or “somewhere outside of”), but never exactly pinpointed. That small Central or Latin American town is seductively placeless.

At the same time, every panel of his is well-ruled and clearly defined, which is what border borders think they’re up to, despite being theoretically, logistically, and politically unstable sites of control. The New Inquiry puts it this way: “They exist unapologetically through baseless contradiction: insurmountable, yet deeply arbitrary.” While insurmountable, the panel border, for Gilbert, sounds more like an improvisation on the surface of the page waiting for an image. As he says in that interview, “Sometimes when you get excited about putting a story on paper, it’s not ready yet. You gotta do the borders.” He rules pages and pages of borders, then sifts through them for the right one!

One of Gilbert’s most recent stories in Psychodrama Illustrated, presumably after having waited for its panels, has turned out to be about Trump’s border wall, of all things. This timeliness threatens to make stable the floating border-town ethos, all the more so if Fantagraphics plans to “do-it-up” as a standalone hardcover and package it as a commentary on the end of the Trump era.

My thesis is don’t do it. No boundaries. Break free.

2. PSYCHOTRONIC PSYCHODRAMA

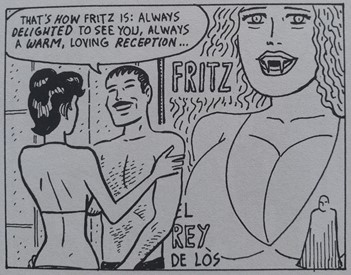

Psychodrama Illustrated, the new series from Gilbert, is a venue for more of his B-movie adaptations, which he’s been exploring since the 90’s when the character Fritz leaves her psychotherapy practice to become a cult film star. Fritz is defined by the vulnerability offered by her lisp, a vulnerability which permits everything to be done to her as she does everything to herself. Her film career first existed as teaser panels, stills from films, poster artwork, and full-page vignettes, then led to single-volume B-movie graphic novels, starting with Chance in Hell (2007).

Those early freeze-frames were a great touch in Love & Rockets: they condensed the visual language of genre (noir, space opera, jungle) into suggestive snapshots. They coexisted with Gilbert’s world of Palomar and beyond, which had already been bending into crime, telenovela, and magical realism, but was never wholly those forms. These pulpy snippets and the books themselves—the corpus of Fritz films—are psychotronic: exploitation, ephemera, trash. Indeed, Chance in Hell begins in a scrap heap under a roiling sky. Here’s Colson Whitehead on Michael Weldon’s term: “The psychotronic movie’s disregard for mimesis, its sociopathic understanding of human interaction, its indifferent acting, and its laughable sets were a kind of ritualized mediocrity.” Gilbert’s embrace of this ritualized mediocrity isn’t to everyone’s taste, but it has nevertheless led to fruitful profusion, obsessive exploration, and mad iteration!

It’s worth remembering that the Fritz movies come in many shapes and sizes, starting with the fact that many remain uncollected. Of those, “King Vampire” (from Love & Rockets: New Stories #4) is the most standalone, a teen clique story full of malaise and curtained with large swaths of black ink. “The Magic Voyage of Aladdin” (New Stories #7-8) is the thinnest, an idea-free romp, but the endless variations of arcing, angular limbs in speedy sword fights form beautiful x’s and shapes on the page. It is less able to stand alone because of its placement in the actual L&R issue: it is framed by characters, including Fritz, commenting on “Aladdin.” “Proof That the Devil Loves You” (New Stories #5) does this more extensively: it interleaves a few pages of the Palomar-esque movie-comic with a few pages of their counterparts in Palomar, alternating across fifty pages. This mirroring is essential to the meaning and experience.

With these uncollected B-movies, the magazine, not the story, becomes the unit, the totality, making it uneasy to extricate. The magazine as magazine always deserves more love, and it highlights how the issue-to-issue seriality is a fulsome aesthetic experience. The hardcover, in contrast, deals in prestige—press, buzz, visibility, reviews, entry into bookstores, onto end-of-the-year lists. “The hardback is the prop forward of the book world: it bashes its way through a crowded marketplace,” according to Phillip Jones in the Guardian.

For comics, the deluxe hardcover is a desirable object for a type of reader-collector: the beefy omnibus, a book like a brick, builds a wall of graphic spines on the bookcase. Hardcovers for novels come first; for comics, they are sometimes the telos, the end-point, finally collected after languishing in newsprint, in old floppies, in magazines.

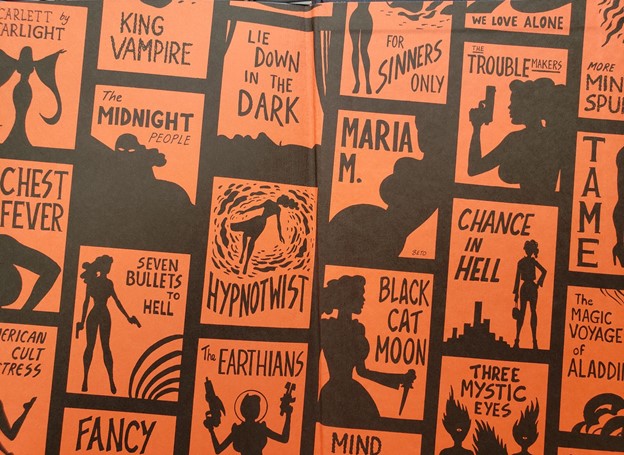

A cliché about hardcover books is that they are respectable and “lavish” (expensive design and production), but with changes in obscenity laws in the mid-20th century the “lurid” has also found its home there (see Louis Menand, “Pulp’s Big Moment”). This contradiction is never more apparent with Gilbert’s B-movie series, beginning in the 2000’s with Chance in Hell, The Troublemakers, and Love from the Shadows. They form a psychotronic trilogy of original hardcover graphic novels with standard design. Each is 120 pages long. Iconic silhouette endpapers hint at the endlessness of Fritz’s movie career—some of which are comics, some to come. Bizarrely, each book has a cover not drawn by Gilbert, as if they are pulp paperbacks containing prose inside, or reinterpretations of classic underground work, like the Criterion Collection’s packaging of films in varied, occasionally dissonant styles.

The trilogy as an ordering concept is also a false front. Gilbert “adapts” a Fritz movie-comic almost every year. This year, Fantagraphics released a flipbook hardcover of Hypnotwist/Scarlet by Starlight, two expanded comics from L&R: New Stories, and while the book is the same size as the trilogy, and boasts the very same endpapers, the design doesn’t evoke that pulpy trade dress. The cover calls what’s inside a “double feature,” but it’s neither special edition film noir DVD nor trashy paperback. It’s comics, baby! Scarlet is a grotty parody of colonialism, and Hypnotwist is a true delight: all unconscious fluidity, with an elegant economy of thick lines and thin. Nevertheless, some stab at relevance hasn’t pierced flesh. The package seems like a bid to stop time, since it’s older material brought up to date, not joining its companions as standalone works. After Maria M., Book 2 wasn’t released on the heels of Book 1, the streak of Fritz films broke, not in terms of quality, but seriality. Love & Rockets was also changing formats around this time too, from annual back to magazine. Whether in sync or not, both Fantagraphics and Gilbert stopped thinking about Fritz B-movies packaged as prestige in the same way. The series Psychodrama is the mark of this change. That said, Maria M. as one complete book did come out in 2019, then Hypnotwist/Scarlet by Starlight this year, and there will be more Fritz collections in the future, I’m certain.

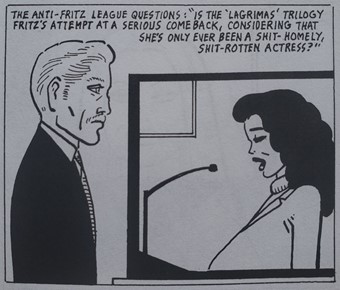

All to say that the tenor has changed, the shape has shifted from standalone to more deeply embedded. Recently, Gilbert has been assembling a new trilogy of Fritz movie-comics: “Little Ones,” “Lagrimas Means Tears,” and Loverboys now form the Lagrimas trilogy, films directed by Fritz. It’s a sort of retcon: Loverboys, already a standalone graphic novel put out by Dark Horse in 2014 (thus outside of the Fantagraphics line), has been incorporated into a new whole. “Little Ones” was published as a two-part story in Psychodrama Illustrated #3 and #4 (2020), and scenes from “Lagrimas Means Tears” are in Love & Rockets Vol. IV #10 (2021), the very issue that announces the Lagrimas saga.

The new trilogy has a fresh claim to sincerity in the world of the comic: “Is the ‘Lagrimas’ trilogy Fritz’s attempt at a serious comeback, considering that she’s only ever been a shit-homely, shit-rotten actress?” Yes, this could be the occasion for a Fritz renaissance: a new series that’s a comment on our times—unafraid to tackle the political landscape with the clarity of hindsight—with an old character who’s more versatile than ever, producing and directing relevant films—the haters be damned. However, the lack of “shit-rotten” awfulness in “Little Ones” means that this comic about the wall is sexless and gore-free. Barely any Fritz. No babes, no Trump, no wall. An un-psycho psychodrama, a Fritz film even more mechanical than the lurid ones thus far.

3. WALL OF REALITY

On September 1, 2021, Bird Photographer of the Year awarded Alejandro Prieto top prize for his allegorical “Blocked.” In the image, a roadrunner in Arizona—no, not that Roadrunner—pauses before a razorwire wall. Animal, landscape, overzealous contraption—no! The photo captures “a sense of bewilderment,” and, as environmental activism, it calls attention to the “habitat fragmentation” caused by the physical border wall. “The wall dominates the image, with the roadrunner seemingly powerless and small in the frame,” as the bird award site says.

That’s often the issue.

The wall, even in protest, is a wall, a block on the imagination. It might be comically plastic in the hands of John Cuneo, warping around Trump’s body, but it’s deployed by editorial cartoonists as a flat screen on which to project American values: those of the Constitution (Paresh Nath) or “Checks and Balances” (John Cole) or, negatively, “Fear-Mongering Politics” (Joe Heller). In these cases, the wall is a metaphor drawn childishly as a wall, and sometimes it’s what’s crumbling, not being built, but it’s usually the sign of an immovable ideological boundary for the cartoonist. Reality is that basic for those people (Kevin Siers).

The wall is a source of scalar distortions for photographers and filmmakers. In the film “Tectonics” (2012), Peter Bo Rappmund makes it up-close and tactile, while also peripheral, unfinished, and invisible. Those spots of invisibility are the film’s best moments, when you’re lulled into accepting a measure of peace or tranquility—no wall in sight, phew—but, in fact, there’s always a patrol helicopter hovering out of frame. A natural landscape that exists untrampled by nation-state xenophobia? Too unreal.

Gilbert’s “Little Ones” picks up on the invisibility of the wall and runs with that false tranquility. There’s no Trump in “Little Ones,” no mention of him, and no physical wall. Even though the wall isn’t present as an image, it’s everywhere else: it affects the speech of the townsfolk, it haunts the scenery of the town, and it imprints itself on the very organization of figures in a panel.

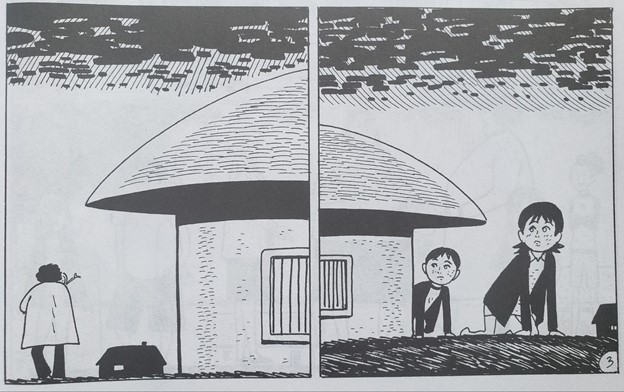

First, scenery. No wall, but other monumental structures: a dome with barred windows, a tree with a hollow hole, a grand cliff face. All three are landmarks of the fictional town of Lagrimas, on the United States side of the border. The dome is a great graphic: it’s a silo, a bunker, a helmet, a toadstool, a Coconino touch that changes in scale from background to foreground. Its grates open in Loverboys and cartoon dynamite flings out! The cliff is only good for murder or suicide, the tree and dome unsuitable for shelter. The place is toxic.

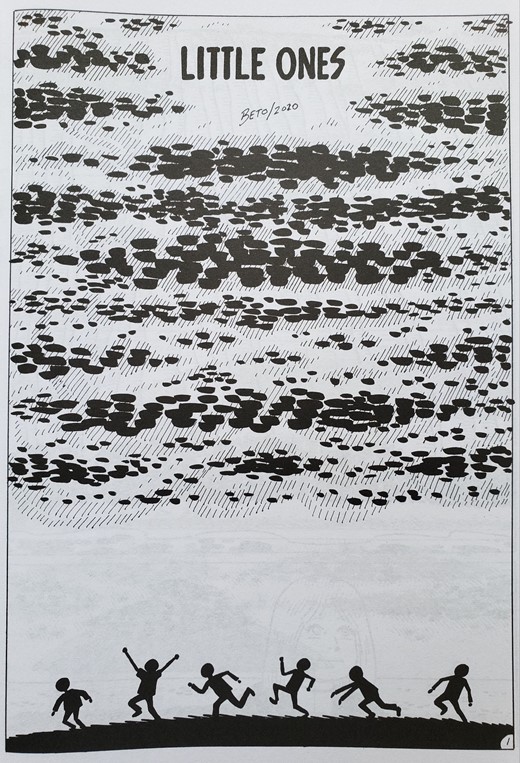

In “Little Ones,” these structures aid and abet the theft and death of children. Kids Rocky and Katya are mysteriously deposited on top of or inside of these structures, and the propelling force of the story is the arrival of two orphans in Lagrimas. The first three pages are silent and textured, showing off the grandeur of the cliff and the magnetism of the dome as young Mindy goes exploring. The title page gives us a chain of characters in silhouette, which is a repeated form Gilbert uses throughout the two-part comic. The form evokes Jordan Peele’s Us, with its cut-out paper people spreading out across the landscape, and Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis, with its planar style isolating and evenly spacing figures in the panel. Splayed out in an accordion, they form a wall of figures in lieu of the wall.

4. CHORAL FORM

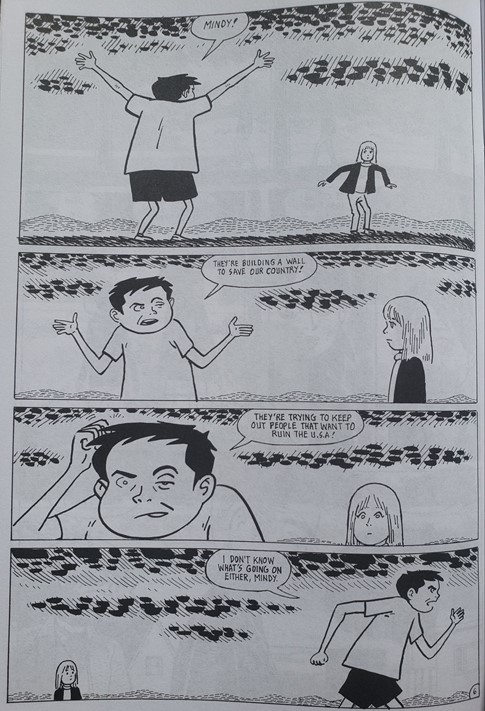

This is because the wall in the comic is only the rumors of a wall. That’s Gilbert’s novelty here. The people of Lagrimas line up and take a side, they align or don’t, they proclaim and push back, and they are aware their opinion exists in relation to others, even if they don’t exactly know what that relation is. On page six, we hear about the wall from befuddled Froggy first, as he shares the news with Mindy, the gallivanting child: “They’re building a wall to save our country! They’re trying to keep out people that want to ruin the U.S.A!” He is either excited by the news or by the excitement, but he’s also scratching his head, in the dark about what it means for himself. We find that out two pages later when the character Alma goads on Froggy: “They’re going to kick you and all Latinos out of the country any day now, stupid.” So what seemed like eagerness or excitement was really an inability to see himself affected by the rumor. He’s a terrible Paul Revere, disbeliever in the message. The sequence ends by crossing the 180-degree line: Froggy’s on the right now as he departs, none the wiser, a visual representation of confusion itself.

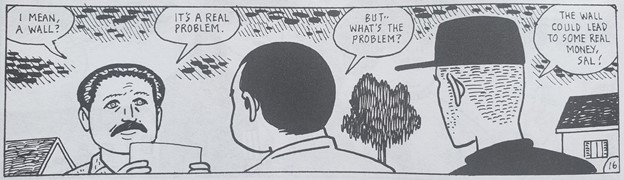

Direct opposition between two people sometimes takes a divided, symmetrical form, traced back to Loverboys. For more than two people, Gilbert uses a choral, accordion form, a.k.a. the wall. This does two things: one, it dramatizes the plurality of voices, and two, it insists on the broken relay of the message. For example, in the first part, Gilbert breaks down the transmission with chiasmus, the crossing over of terms from one side to the other: wall, problem, problem, wall. The question marks shift and money is introduced, such that the original terms are reversed and upended. Sal’s opposition meets resistance when his own words are turned around, the textual equivalent of Froggy’s flip. This panel is widescreen enough to evenly balance out three heads and four speech balloons. It’s the internal mechanics that make a farce of rigidity. Gilbert’s artistic practice of ruling the borders first is not a fantasy of controlling the shape and size of the story. It’s to view the story, seeing it decay by groupthink and warring opinions.

The world of the comic is typical Gilbert: marked by depravity (CW: rape, pedophilia) and defined by noir. Movers, shakers, bosses, workers, shitheads, perverts. No thugs or molls this time, but kids. Crime has always been the vehicle for the movement of unseen forces—deals, shipments, pressures, economics. Here, it’s the prospect of the wall and work, after mass layoffs at the plant, and this prospect affects the writing in the comic. It warps people’s words, to the point where “Little Ones” reads like a Flarf experiment whenever it is about the wall, as if the dialogue were formed by auto-complete (“border wall will blank”).

To wit: “The building of the wall between the U.S. and Mexico will cost the American taxpayers millions when that money could help poor families, veterans–” (4.2), “The wall means more jobs for us Americans!” (4.2), “Who’s going to pay for this wall” (3.17), “Yeah, we should be putting up that wall, not Mexico!” (3.17), “Look, it’s already against the law to sneak into America–the wall will simply be a deterrent!” (3.20), and so on. Flarf’s poetic mission was “to trawl the internet for preexisting language,” according to Andrew Epstein, “misspellings, stupidity, racism, and xenophobia” to boot. What if all the talking points of the internet came to life and had their avatars in the denizens of small-town life?

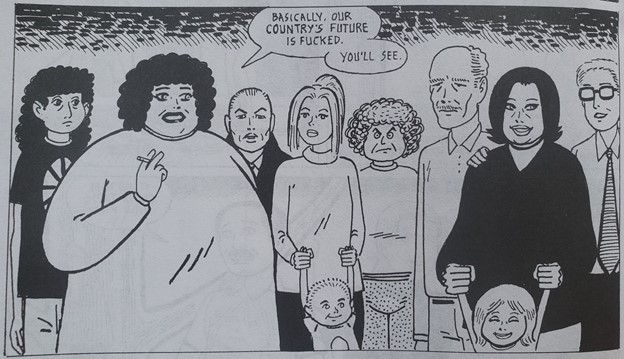

The second part of the comic resolves some of these stilted disputes by using that choral form to communally repudiate racism—no, not really. Apart from calling Alma “racist trash,” there’s just more internet-speak. Fritz makes it plain: “Basically, our country’s future is fucked. You’ll see.” The panel has ten faces and mixes moments of joy and doubt. It’s a group portrait that would be cheesy were it not for Fritz’s tweet-as-dialogue. Thankfully even the didacticism is Flarf: the character who asks, “What kind of future can we expect for the little ones?” is a pedophile. He’s killed, since justice in Gilbert’s comics is what goes around, comes around. That’s the closest thing to a definitive ending. The future stays open, like the status of the wall: “It’s been months since–and there’s still an ugly cloud hanging over the town…” Gilbert’s clouds are always beautiful even if the writing isn’t.

5. THE FRAMES

Of course, I want Gilbert to remain in print forever. I can see a Psychodrama Illustrated collection. I can see a Fritz B-movie collection, collecting the uncollected. I can see the full Lagrimas trilogy bound together. And I can see a slim Little Ones hardcover, god forbid. If “Little Ones” is collected as Trump comics, then that would wall it off from the ephemeral, changeable experimentation of the whole project. Maybe that’s marketable, but at the cost of Gilbert’s compulsive and atmospheric wanderings.

On its own, the comic wavers, bound to the empty political discourse it skewers. But Gilbert’s ingenuity is restlessly building frames around the piece so that it’s never isolated. Comeback, trilogy, saga, psychodrama. Although a page might be complete when the panel borders finally meet the story, the real drama for Gilbert is continual and unrealized. The borders were always dissolving.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply