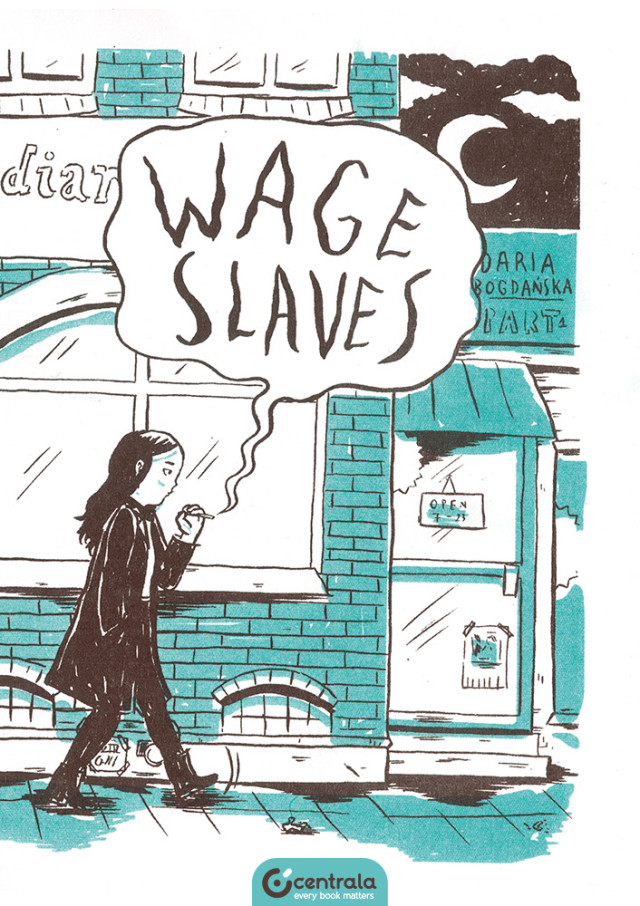

Wage Slaves is an autobiographical account of Daria Bogdanska’s struggles and involvement in workplace organizing and union politics. We find Daria (Bogdanska’s cartoon avatar) arriving in Malmö, Sweden from Poland via a brief stint squatting in Spain. She is enrolled in a comics course at art school and is immediately embroiled in the bureaucratic nightmare that is organizing residency rights. Needing to self-fund her studies but lacking a social security number and fluent Swedish, she ends up securing a job at a local restaurant run by a man who preys on unregistered migrants in order to avoid providing contracts or sufficient pay.

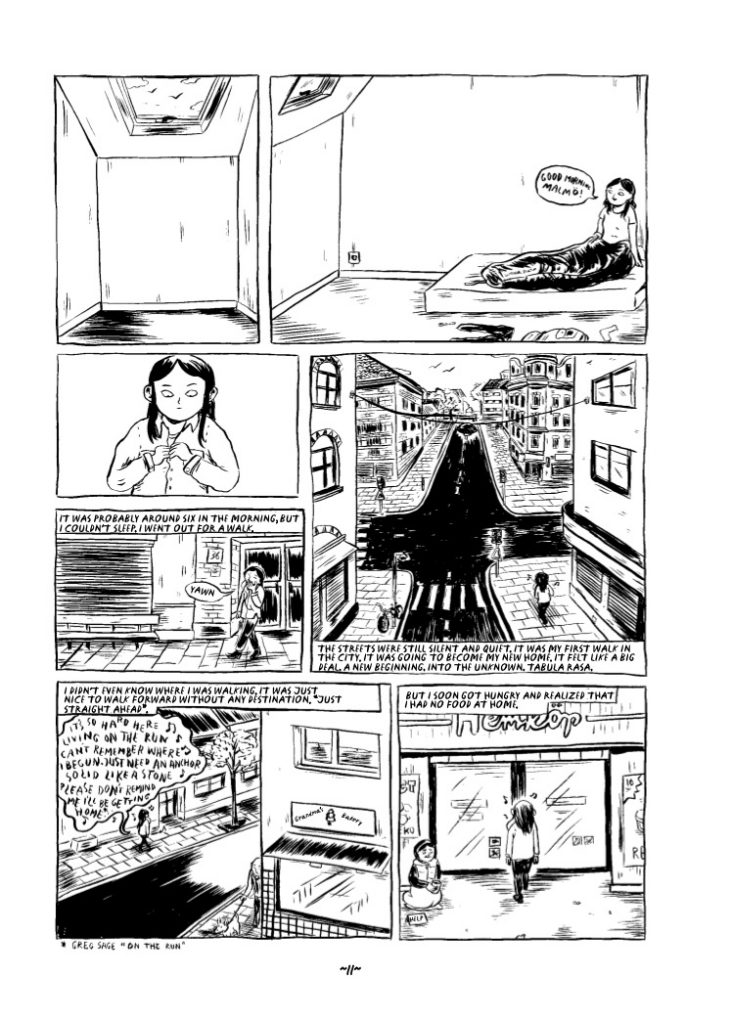

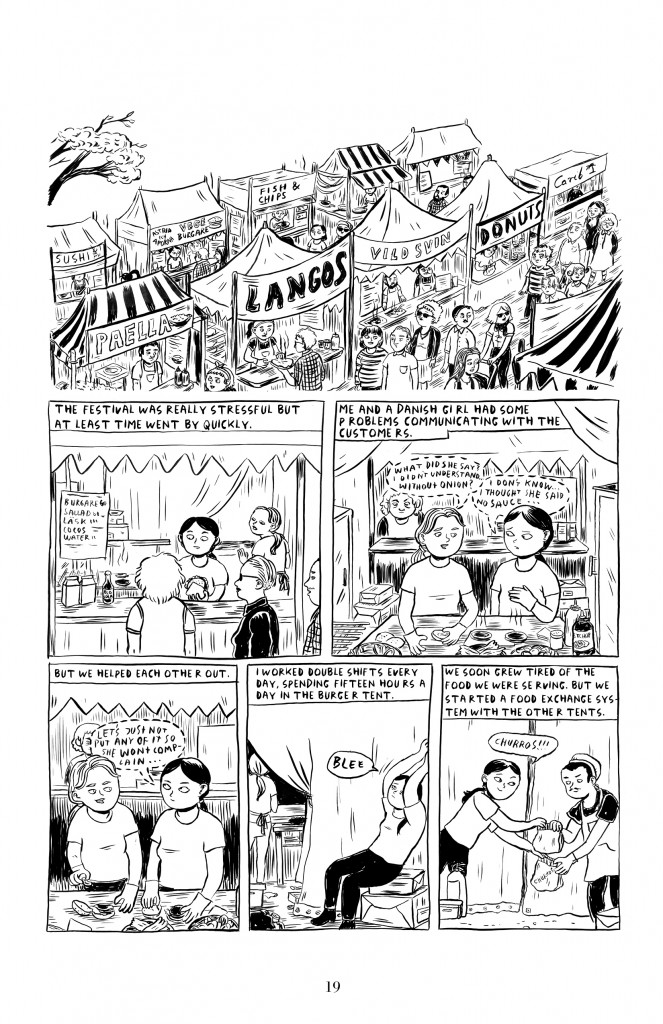

Aside from a couple of flashbacks, Wage Slaves is told chronologically in the past tense. While it is generally oriented around people and dialogue, Bogdanska includes world-building details such as passers-by and shop fronts into the city street scenes. Much of the story takes place in the restaurant she works, where she deals with customers who are both unaware of her presence and antagonistic towards her in equal measure, and where she also becomes aware of her exploitation by a boss who makes his staff reliant upon him, and thus uncritical. Notably, very little is said of her education. Through work, Daria becomes acquainted with some of Malmö’s Bengali community and other undocumented workers accepting payment in cash, who otherwise rely on whatever support their families can offer.

The concept of wage slavery has been traced back to the 18th century’s then-recently urbanized populations, whose left-wing factions argued that the burgeoning capitalism of the industrial revolution decreased their access to a good life and restricted the continuation of rich cultural traditions. The term has been readopted since, and currently sits well as part of the attempt to define our current and near-future as a neo-feudalist one dominated by the logic of rentier capitalism. I think Wage Slaves could be understood as a representation of what is being theorized as the rise of neo-feudalism. If Daria had got a job delivering food for Uber, this connection would have been a little more explicit, though the story does a good job at highlighting the lack of agency that many frontline workers feel they have in their places of work, and also their precarity in terms of housing, which are two key traits of our inhumane economic system.

Wage Slaves is not only an economic commentary. Though the book’s title suggests that this is a story mostly concerned with the material and political circumstances in which a life is lived, a good chunk of the narrative is dedicated to Daria’s increasingly anxiety-inducing love life. Issues around abortion, open relationships, various forms of solidarity, and the way in which inequalities are split unevenly across different social groups are also explored. Wage Slaves does a good job at demonstrating the varying degrees to which different Europeans have access to different privileges across the European Union. For example, in one flashback, Daria has to travel to Sweden to access an abortion clinic (as of 2021, the procedure is still illegal in Poland).

Wage Slaves feels honest and open-minded. Take, for example, the sequence in which Daria steals a jumper she can’t afford but needs in order to keep warm through the Scandinavian winter. This action is neither excused nor critiqued; the book asks the reader to gauge the ethics of such an action not from a moralistic standpoint but through a consideration of the context in which it occurs.

There’s plenty of detail when it comes to how Daria joined a union and thinks and works through (often in collaboration with others) to the concluding action. In that sense, this is a pedagogical comic. The work’s concern with detailing, in an almost documentary style, the ins and outs of political activity results in Wage Slaves at times tending towards telling rather than showing. This is especially the case in the first forty pages which contain a hefty amount of written exposition. Bogdanska’s cartooning, however, has enough charm, and her pacing and plot structuring are speedy and clear enough, so that sticking with the work is a rewarding experience.

The characters have a bendy, Marjane Satrapi quality to them, but Bogdanska’s lines are much scratchier than Satrapi’s (she’s been compared with Julie Doucet), which captures well the energy of the punk rock venues and various squats and basements that Daria finds herself immersed in. Bogdanska displays a deft ability to employ cartooning’s potential to relate complex emotional processes through the subtle transition of facial expressions.

Being someone who lives in the European Union and has moved countries more than once myself, there’s a lot I can relate to here, and a lot of it rings true, even if my own experiences have been quite different in specific ways. More broadly, this book fits into the discourse around contemporary employment practices. Those practices, which place workers into precarious positions and turn each of them into a hustler, are made possible thanks partially to how the labyrinthine legalese and paperwork of supposedly “developed” countries creates grey areas into which migrant communities and individual migrants, especially poor ones, can fall. The inability for recent arrivals to fully integrate because of residency and visa restrictions etc. creates situations where increasingly large proportions of people are disenfranchised from civic life.

My reservation with trying to make the term “wage slavery” a point about which we should rally against is that is hard to disentangle the word slavery from the ongoing struggles to define the legacy of the Euro-American slave trade. Large portions of Europe still either deny, ignore, or play down its significance (though it is true that not all of Europe was directly involved in enslaving Africans, today’s European bloc remains structurally racist). A common argument from the right is that all empires and cultures have made use of slavery, so why make a fuss about ours? Wage slavery could easily be co-opted by these voices to wrongly universalize and ahistoricize the term. In addition, there’s an anti-Semitic trope in which Jews are said to be Christian Europe’s moneyed overseers. Slavery relies on a slaver, and it’s not certain that society today is clear-eyed enough to rightly assess who is driving present-day wage slavery, which leaves room for prior existing xenophobias and racisms to exploit this discourse and further promote themselves. Bogdanska’s book shouldn’t be disregarded because of this; it is specific enough to avoid being confused with bad faith arguments, and it’s an inspiring example of the importance of fighting back by punching up. But these concerns should be considered before the term is taken to those outside of the particular circle in which Wage Slaves is likely to be read.

As a comic, Wage Slaves isn’t perfect, but it’s certainly an empathetic example of a politicized life narrative, an insight into a deeply troubled system, and a story which could spark fruitful conversations. Importantly, it’s clearly a labor of creative love: the best sort of labor there is.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply