Elkin: Memory is a tricky business, isn’t it. You need it in order to make sense of the present as much as you need it to make sense of the past. But memory is hazy. What you remember from experience is different from what you remember based on stories or photographs. Sometimes it’s hard to place yourself in time. Trauma doesn’t help with that either. It can bring into full relief that which you might want to forget, just as it colors how you see yourself in those moments, as well as the present day.

But memories are necessary for self-reflection, and self-reflection is necessary for growth. When what you base your understanding of yourself is clouded in the miasma of time and trauma, how you reflect upon yourself and what lessons you glean from such an exercise can become suspect.

Tie this exercise into the history of a place — a history told in snippets by those with a particular perspective and/or ax to grind, then it really becomes a story of not the self, so much as it is a story of choices and intent.

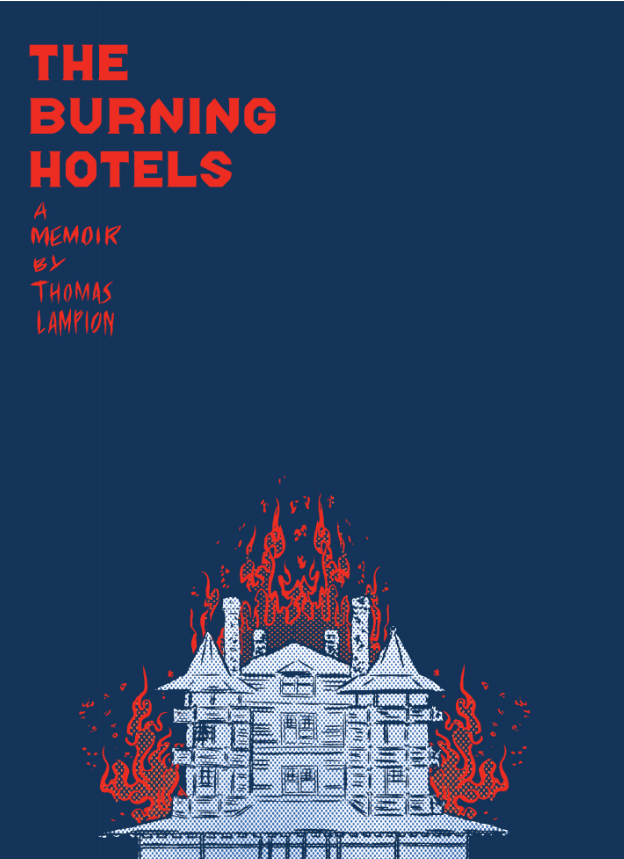

So it is in The Burning Hotels, a new graphic memoir by Thomas Lampion (published by Birdcage Bottom Books), a work that desperately tries to make sense of the present by revisiting the past.

As with all memoirs, The Burning Hotels is a revelation of discrimination and druthers. It is a monument to the story Lampion wants to tell about himself. It is a testament to how he wants the reader to understand him. It is also a paean to place — a place that holds personal meaning, community understanding, and serves as the framing device for the opportunity to make sense of everything that has led to a moment. It is a place marked by burning hotels.

In The Burning Hotels, Lampion is able, through all the tricks of comics-making, to turn place into self and self into something more.

Silva: As you know, Elkin, I struggle (mightily) with autobio comics, such are my limitations. Which is why, perhaps, you’ve set The Burning Hotels in our path, always playing provocateur when you’re not trying to be the most low-key charming chap at the salon. I see you.

I’m struck by your opening sentence. Not about memory being a tricky business, that’s a given. No, what tickled my curiosity was you chose to end that sentence with the words “isn’t it” and a period. That’s really more of a question, isn’t it? It is for Lampion. As it is, I would argue, for the reader of The Burning Hotels. All these memories—all these digressions on digressions and memories dangling like that rope tied to the church bell the Lampion children fling their bodies at as they call the faithful to Sunday service—aren’t so tricky, they’re not hazy or half-remembered, quite the opposite. They’re Lampion, in full, plain and simple or as you say, “the story Lampion wants to tell about himself.” To which I would add and maybe the tragic history of hoteliers in a small western North Carolina town. It’s this second part that elevates The Burning Hotels from (sometimes) navel-gazing of auto-bio/diary comics.

How I learned to stop worrying about this diarist’s deviations and (at least) love or better, come to terms with The Burning Hotels was to not expect it to be what it is not, a straightforward narrative. The ontological hodgepodge Lampion lays out are his experiences and his alone. As is always the case, one memory triggers another and another and so on. These memories burn out or fade away in equal measure, meaning all are equal, no more or no less than a previous or subsequent memory. Some resonate louder than others (the most powerful being Lampion’s autism and his father’s racism) but Lampion picks up and drops these incidents with little follow-up or follow-through. His experiences are compelling and ring true as any occluded by the penumbra of memory. Late in the game he introduces his (possible?) substance abuse to soften his pain. What pain specifically? His relationship with his father? His autism? He admits, “much of my memory was lost in the process” of drugs and alcohol. Really? He seems to have remembered enough to frame his narrative, so …? I sympathize with Lampion’s struggles and see myself in the wonder of watching a movie for the first time. This isn’t ‘sad bastard theatre,’ more like a scruffier, more indie (if that’s possible), Harvey Pekar. “I don’t feel like I had a bad childhood,” Lampion says, adding, “it had the briefness of a vacation.” Likewise, The Burning Hotels, if not for the burning hotels.

I’ll pause where you left off: “self into something more.” That’s the ticket. It would appear we agree Lampion’s time spent at the library was time well spent, but to what end? Is this a case of, “reflect what you are, in case you don’t know?” And we’re going to have to reckon with that ending. But that’s for another of all tomorrow’s parties, yes? Yes.

Elkin: Remember, though, Silva, that according to Lampion, “This book is my child.” In a memoir, especially one that dabbles in its easy, conversational style with making sense of complicated people in a complicated place making the most of their complicated present (albeit in the past), so many of the choices that the memoirist makes is a matter of moving to the future. Much like a parent who gazes upon their child and only sees that which they will become in the hopes that whatever journey they take gives meaning to whatever present struggles exist, so too reflects the pages Lampion produces.

It’s all a matter of hope? Understanding where you came from helps you frame who you are and, perhaps, gives you a map to the future. Or, if nothing else, gives purpose to the present. Or, in the midst of stasis — be it the result of choices or circumstances (such as a global pandemic), it provides a bedrock. As Lampion says, “The future is so uncertain all I have left is the past.”

Isolation breeds rumination. My week beats your year.

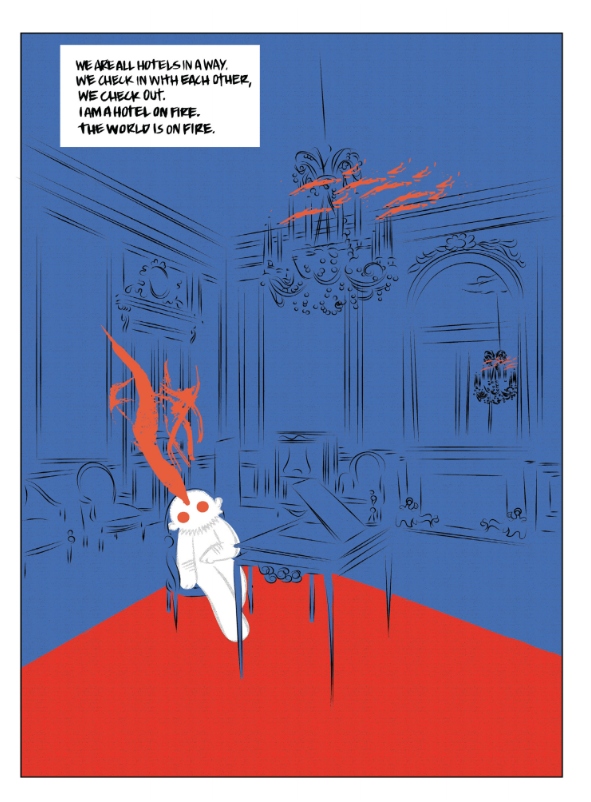

A memoir is shaped by the one doing the remembering. Framing allows only that which has bubbled to the surface. It is a journey, but it is also a passing through. There’s a moment about two-thirds of the way through The Burning Hotels where Lampion tries to make sense of the choices he is making in telling his story. There’s a barely sketched out full-page spread where Lampion draws his outline sitting at what appears to be a desk in what appears to be a lavish hotel room. His eyes are perfect red circles. There are red flames or smoke emanating from a hole in his forehead. In a text box in the upper left corner of the page, he writes, “We are all hotels in a way. We check in with each other, we check out. I am a hotel on fire. The world is on fire.” Here, place and self merge. Past and present are one. He is within and without. The inexhaustible variety of life all have stories to tell, and each of those stories reside for a moment within the individual, unpack their frillies and briefs, only to travel again to other lives. But each moment leaves its detritus. It piles and compiles and shapes the individual. There’s no way to tell one’s story without sifting through.

It’s amazing that more of us aren’t burning.

But what wisdom is to be garnered in the fire? Is life a casting off or is it ultimately a returning? I know you want to talk about endings, Silva. Here is your opportunity.

Silva: “We are all hotels in a way,” ain’t that the truth? Call it the sanctum sanctorum of The Burning Hotels, if such a reference holds water nowadays with ‘the youth.’ As always, Elkin, you put me in a mood. Before ‘endings,’ let’s recall beginnings, specifically, maps.

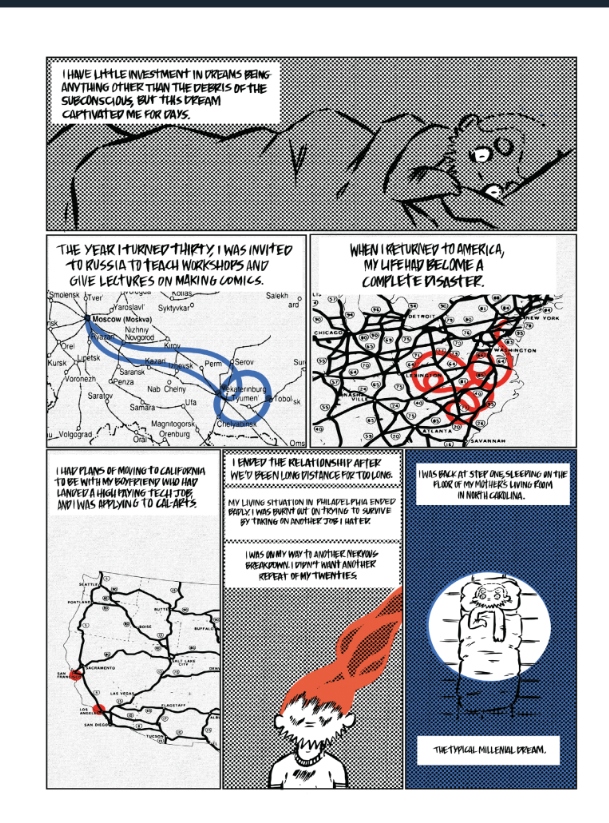

After those two desperately sketchy opening pages, Lampion draws himself abed lying like a colossus above the page. It appears as if he’s looking down at three maps, the framework of The Burning Hotels. The first shows his journeys in Russia where he taught workshops about making autobio comics, the second, the twists and turns of his subsequent return to the states, and the third, a map of the West Coast. The first two represent actual events, moments in time, the third is the proverbial ‘road not taken.’ Lampion had planned to move to California to be with his boyfriend, instead they broke up and Lampion (eventually) landed on the living room floor of his mother’s North Carolina home. Of course, his return to N.C. will send him headlong into reconstructing his past through The Burning Hotels and that killer realization/metaphor.

What at first appears as jackstraws of memories turns out to be, to borrow a phrase, a portrait of the artist as a young man. How can it be anything else? Lampion like the artist of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce Stephen Dedalus, burns, burns, burns — ditto those “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection” who will follow forty years in Joyce’s wake — for what comes next. Is it ‘The Future,’ yes and no. There are no maps of that further shore and the reports from those who have returned are sketchy at best.

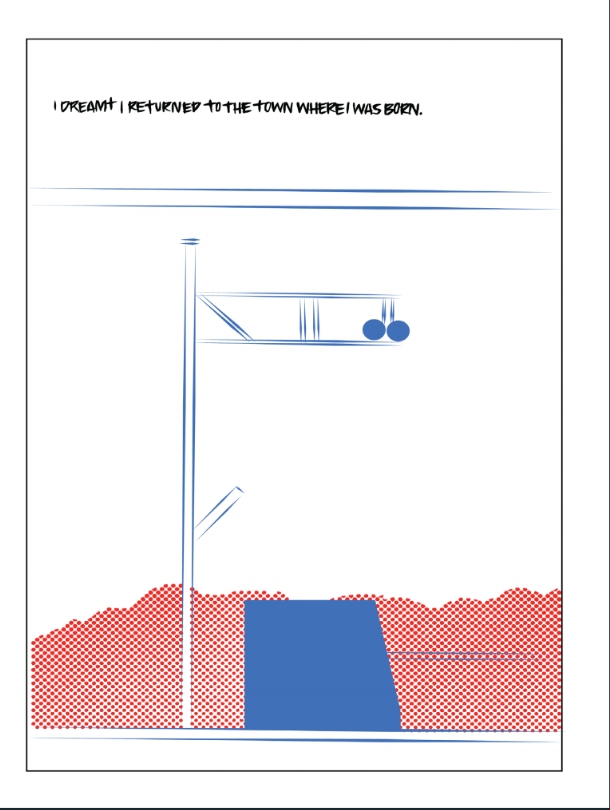

The Burning Hotels is bookended by identical background images of buildings and a railroad signal. The change Lampion makes at the end is to foreground himself as he walks through these nondescript pseudo cityscapes (curiously he hangs the moon in the same spaces where he previously put text). At the start, these backgrounds served as a dream Lampion was having before waking up and assessing his current state of restlessness. At the end, he has become both the dream and the dreamer.

Which reminds me of that Monica Bellucci dream. You know the one David Lynch has in Twin Peaks: The Return? The one where he repeats something Bellucci says to him, “We are like the dreamer who dreams, and then lives inside the dream.” Troubled, Bellucci asks: “But who is the dreamer?”

Indeed.

This burning, of hotels, in dreams and memories? It’s all the same coin, only different sides. That’s your ‘wisdom,’ Elkin. Hotels are always burning down and being rebuilt and if we are all hotels … well then. As for us, Elkin? We shamble after those mad ones who burn, burn, burn … and everybody goes ‘Awww!’

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply