Content Warning: This conversation will discuss themes of It Hurts Until It Doesn’t, which include neglect, abuse, trauma, and suicidal ideation.

Over the last year, I’ve taken a much greater interest in graphic medicine, comics that tell stories of illness and health. Perhaps this is because of my professional work in primary care, and perhaps it’s because of the rawness of these works. I think about cartoonists like Marnie Galloway, HTMLflowers, Nagata Kabi all of whom make significantly different comics, have different illustrative styles, and tell remarkably different stories. Despite their differences, each of these cartoonists has a body of work that shares an undeniable core; that of powerful emotional resonance.

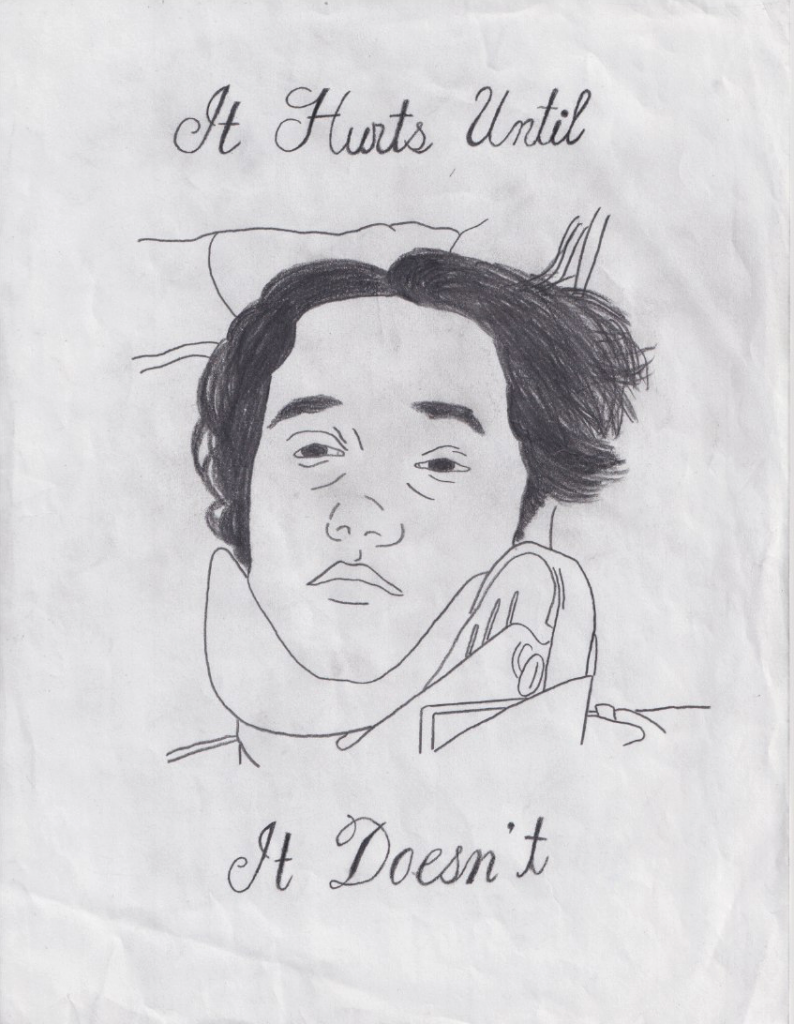

At the recommendation of one of SOLRAD’s contributors, Tony Wei Ling, I recently purchased a copy of Lanei Kasir’s It Hurts Until It Doesn’t, a self-published digital comic on ITCH.io, and found a comic that was harrowing in its depiction of physical and mental illness, abuse, and suffering. It is also a remarkably beautiful work. At my insistence, my co-conspirator Daniel Elkin also read Kasir’s work and offered to discuss it with me.

Like previous entrants into this series entitled Critical Conversations, what follows is our discussion of It Hurts Until It Doesn’t. Enjoy!

—————–

Alex Hoffman: Daniel, I wanted to start this conversation with a pulse check. How many “graphic medicine” comics have you read?

Daniel Elkin: Way to put me on the spot right out of the gate, Hoffman. The answer is, I’m not sure. I can point to the work of Nagata Kabi and, of course, there’s Dancing After Ten by Vivian Chong and Georgia Webber. Barking by Lucy Sullivan also comes to mind. After that, things start to get a little fuzzy, mostly because of my brain, but also because I lack the necessary clarity as to what makes a book fall under the “graphic medicine” category.

Alex Hoffman: Well, that’s an understandable caveat. It’s a relatively new categorization of comics, so I’m not surprised that you haven’t seen it much. That said, I bet you’ve read quite a few graphic medicine comics. Ian Williams, a cartoonist and physician in the UK, coined the term “graphic medicine” in 2007. Essentially, graphic medicine refers to comics that embed the medical narratives of patients or caregivers to tell personal stories of illness and health. Think John Porcellino’s Hospital Suite, Dash Shaw’s Doctors, or Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? by Roz Chast. Does that help any?

Daniel Elkin: It does, thanks. Do graphic medicine books have to be non-fiction? Would you consider something like Upgrade Soul by Ezra Claytan Daniels to fall into this category?

Alex Hoffman: I don’t think graphic medicine has to be nonfiction, and you could make a great case that Upgrade Soul is a graphic medicine narrative. Kevin Wolf wrote a review of the book for graphicmedicine.org, that gets at that very point. Just from the standing of medical ethics and personhood, I think you have a strong argument that it is “graphic medicine.”

Daniel Elkin: Nice. Thanks. So I guess we should start talking about It Hurts Until It Doesn’t by Lanei Kasir. This was, for lack of a better term, a “hard” read. I know you’ve been wanting to talk about this book for a while now. So, what is it that has drawn you to it?

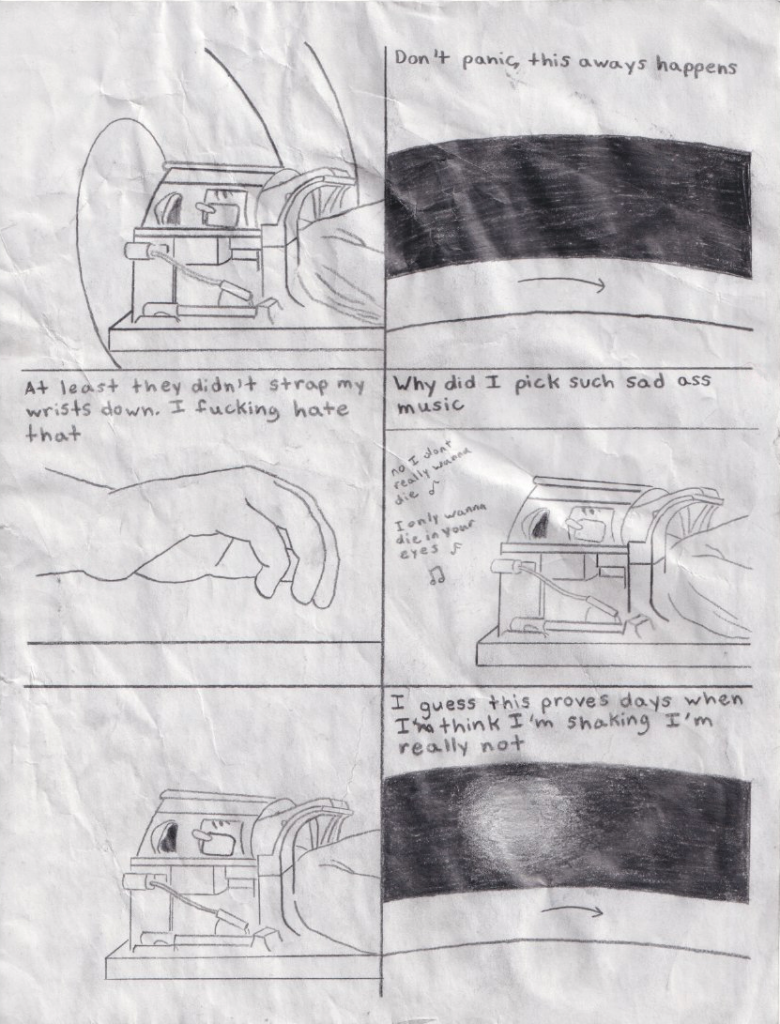

Alex Hoffman: I think the first thing that strikes me is Kasir’s illustration, how powerful it is. I’ve always been fond of graphite illustration, it feels so much more alive to me than ink. There’s potential in graphite that you can’t find in ink. But more than that, in this book you can feel the rawness of Kasir’s mental and physical health in their line. There are so many little moments where I think that this kind of vulnerability and candor couldn’t be contained with ink. And I do think that the vulnerability, the rawness, the candor, all of those things are an important draw to this book for me, but I also think It Hurts Until It Doesn’t is a remarkably complex story of abuse and trauma centered around Kasir’s disability, which is caused by Hereditary multiple osteochondromas (HMO), a disorder that causes bony tumors to grow throughout their body.

Daniel Elkin: I, too, appreciate Kasir’s decision to keep the art loose and unpolished. There’s that sort of “everyman” feel to the book, as if it could have been drawn by anyone, anywhere – which, in its own way, shows the craftsmanship that Kasir is capable of, especially when there are those moments of more refinement – there is something that happened in my brain that jarred it in those moments – enhancing the visceral experience of It Hurts Until It Doesn’t.

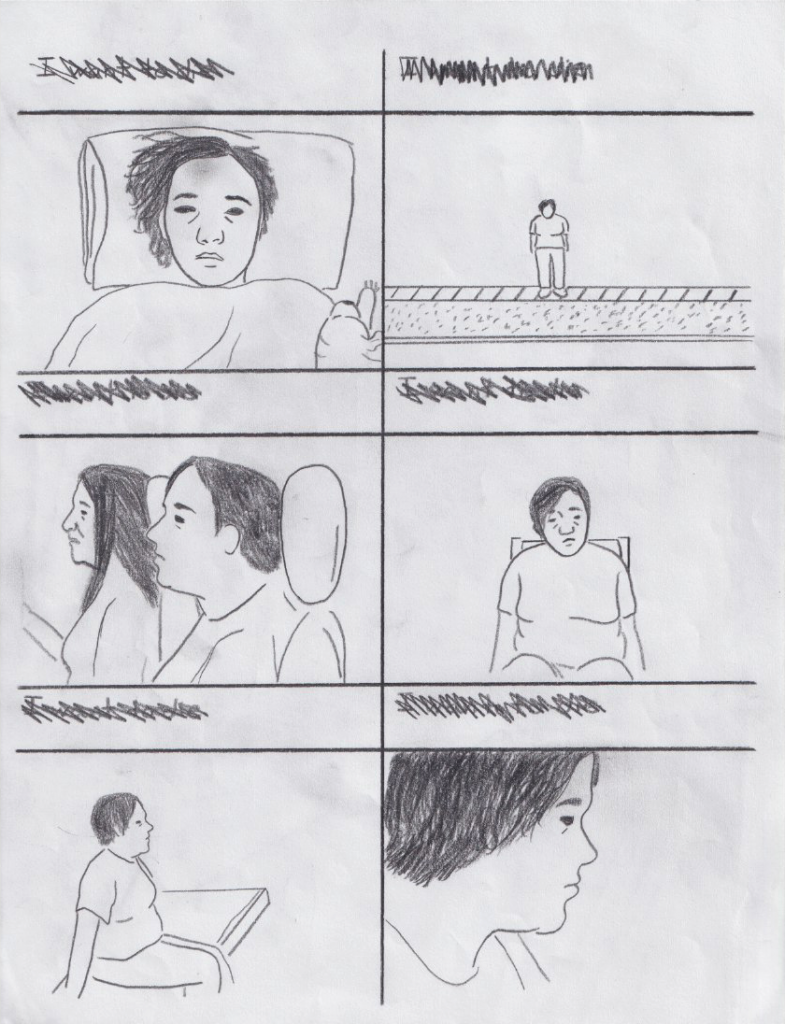

And this IS an emotionally gripping story – it seems to almost ride that emotional content as its narrative – making it a little challenging to parse at times, yet always churning with that power. I really appreciated, as you alluded to, that there is sort of two intertwined things happening in this book: there’s the trauma of dealing with the consequences and effects of HMO, but, equally as charged, there’s also the trauma of the abuse within the family dynamics (as well as the healthcare industry). Which aspect of the story did you feel more drawn to, Alex?

Alex Hoffman: I think It Hurts Until It Doesn’t is one of those comics that you really can’t dissect into aspects. In my mind, I have a hard time separating Kasir’s abusive family situation from the healthcare they need in order to live. Kasir has access to a broken healthcare system, which causes its own traumas, but even that brokenness is being gatekept by a broken and harmful relationship. All of it acts as accumulation, a 1 + 1 = 5 sort of feeling.

I do appreciate that you touched upon one of the things that I believe drives the comic, that sense of emotion as narrative. I think that’s what elevates this work from good to great (and also from hard to harrowing). There’s a sense of “non-chronology” to the comic, or perhaps the moments depicted in this comic are the times that break through the water tension of Kasir’s extraordinarily difficult situation.

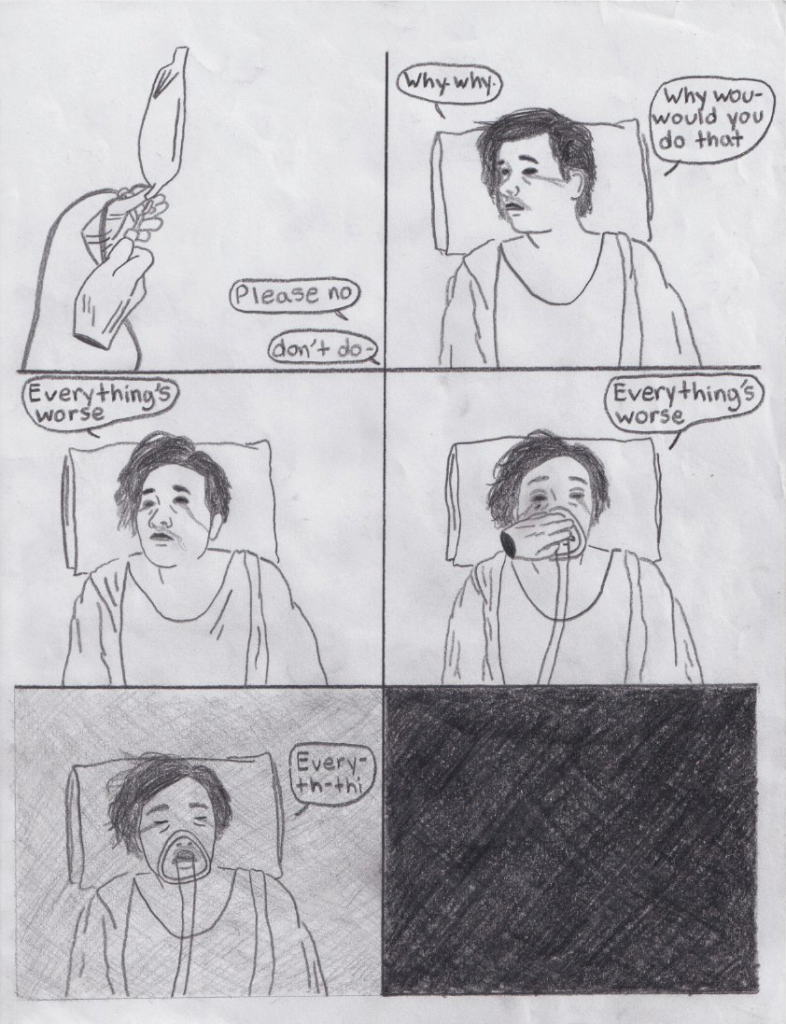

One of the things that I wanted to talk with you about, and I appreciate that this is a difficult subject, is the way Kasir illustrates moments of declining mental health and suicidal ideation. As someone who has struggled with SI for most of my adult life, I found quite a few of these scenes extraordinarily hard to read. The struggle that Kasir illustrates in those pages of scratched-out dialogue is powerful and, in an unexpected way, one of the more uplifting moments of the comic.

Daniel Elkin: Studies have shown that individuals living with chronic pain “are at least twice as likely to report suicidal behaviors or to complete suicide.” Coupling this with a caregiver who dismisses the problem, saying things such as, “You really would be better if you just took care of yourself…” and “You know how much money you cost me…”, as the mother in It Hurts Until It Doesn’t says, only compounds the situation. Add to that stew a health care system, like you said, which is broken and, unfortunately, the sad reality is that it is the exception, rather than the rule, that someone in that situation would not consider suicide.

To put this in one’s art, to be forthcoming and vulnerable in this manner, is an act of courage. To be able to convey it in such an emotive and poignant way as Kasir has here is an act of genius. The presentation becomes almost a chant, its rhythms dictated by panel breaks and augmented by the visuals they create. There is a will to live that surfaces throughout the resignation, and, I assume that is what you are referring to when you call these moments uplifting – the fact that even at the brink, there in the darkness, poised at the moment, their choice is still to go on.

Alex Hoffman: That’s a good encapsulation. There’s a small amount of hope, if you can call it that, in looking at a handful of pills and then putting them back into the bottle. And I think you hit on something that I recognize now, this idea of “chanting,” as you called it. Perhaps it’s that the movement of the comic is more of a sine wave — there are ups and downs in intensity, but there’s not a narrative arc in the classic sense, and Kasir doesn’t really give readers an opportunity to experience any release from that wave until the book is over.

One of the things that I thought about as I was reading this comic the second or third time was the way that Kasir draws eyes – dark black with graphite, filled in, sclera to pupil. It’s remarkable how much that small creative decision communicates to readers – Kasir’s moments of pain, the abuse they receive from their mother, the trauma, and dehumanization of the medical procedures they have to undergo. There are moments where we see them look like they are just barely holding it together – those moments with friends in the middle part of the book are especially harrowing.

Similar, but not quite the same, are these small discs that Kasir draws on their body, which I assume represent the bony tumors that HMO causes. They’re everywhere, and it seems impossible to imagine how debilitating and painful they must be.

Daniel Elkin: And by drawing the reader’s attention to them in this manner, Kasir allows us all to emulate that focus – that narrow pinpoint of pain that consumes almost the entirety of reality as it flares. Again, this is Kasir demonstrating their ability to use their art to communicate on that emotional plane, allowing their readers to create their own narrative from the connection created.

I do want to circle back to something you said above, though, and that is the idea that this book provides a “release” at the end. I’m not sure I agree with you, so I’m hoping you might expand on that a bit more.

Alex Hoffman: I actually don’t think it does, really, but there is that final “page turn” if you will when the narrative is over, and you are no longer co-creating this landscape with Kasir, that lets the reader escape from its intensity. Otherwise, It Hurts Until It Doesn’t grabs hold of you and doesn’t let go, and it can be suffocating in that way. There is no escape. I think that narrative and emotive intensity shows Kasir’s mastery of the form. Perhaps that was part of the reason you and I wanted to talk about this book, despite how difficult it was for the two of us to read.

Daniel Elkin: Is there where we start talking about the transformative power of art? Or is this where the cranky old cynic in me starts to question the value of plumbing these sorts of depths and immersing myself in misery?

I know there is value here. In the communicative aspect of works like It Hurts Until It Doesn’t. It reassures us that we are not alone in our pain or our isolation or our fucked up circumstances – there is that “community of misery is still community” thing that I know has value to those of us who need it. But I wonder if, by not giving us any resolution – rather just a continuation of the cycle of pain and abuse with which Kasir ends this book – it serves to perpetuate rather than add to or provide relief.

I engaged fully in this book and I am glad that I read it. I would be hard-pressed to recommend it to others without a tome full of caveats, though.

Alex Hoffman: In my experience, it is through other people’s suffering that sometimes we find our own healing. Being open to that experience, to being vulnerable enough to let it affect you, can be hard. But that’s part of the reason why it works.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply