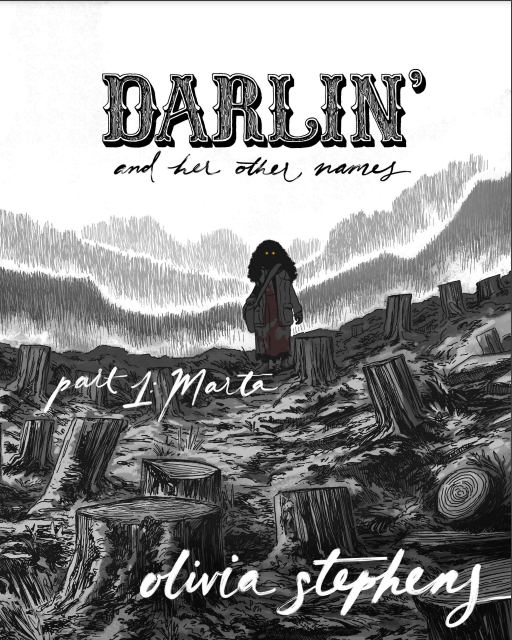

Darlin’, and Her Other Names is interested in things we can only say with our eyes and the moment that skin breaks. The werewolf-western-horror-romance is what it says on the tin, and delivered with sincerity and deftness of narrative. In the middle of the American expansion west, we follow two strangers who meet and forge a partnership in a moment of mutual desperation. In this book, cartoonist Olivia Stephens flexes raw precision in the way she draws imperceptible emotions or creates the static that hangs between two people. I chatted with Stephens about what led her to this work after two graphic novels and a streak of writing residencies, the link between the American West and wolves, and how her process has changed through making Darlin’.

Chris Kindred for SOLRAD: What was the impetus for Darlin’? I know you’d been thinking about werewolves and black life during the westward expansion (please correct me if I’m inaccurate here), but what made you go “I have to make this story [now]?

Olivia Stephens: Darlin’ started as a survival mechanism. The first iteration of the story came to me at the end of 2019 after I’d been living in Oklahoma for a year. I’d moved there for a long-term artist residency which I’d hoped would be a fresh start. But by the first year’s end, I knew I’d settled into an openly hostile environment. A place and organization that was actively detrimental to my physical and mental well-being.

And when I found myself living inside that kind of friction, my mind sought relief wherever I could find it. This often comes in the form of characters and stories. So it’s unsurprising that I retreated to a story idea where two people live with a power that is misunderstood and maligned, but who are still capable of expressing tenderness and care towards each other.

In the beginning, I lacked the specific historical framework for Darlin’ and Edgar. But I knew they’d be surviving in a place that was geographically close to my own site of survival, and that it would take place during the height of the US government’s wolf extermination campaigns. Once my research helped me place who my characters were within history, it was time to work.

CK: Tell me more about your research. What kind of resources did you end up finding as grounding for Marta and Edgar?

OS: I actually started where I was standing at the time. I had not been aware of the Greenwood neighborhood (aka Black Wall Street) in Tulsa before moving there, and it opened my mind up to research other Black towns founded after the Civil War in Oklahoma, Texas, and other states.

Eventually, I encountered the Exoduster Movement, a mass migration of thousands of recently freed Black Americans into Kansas during the 1870s. Not only did this time coincide with wolf extermination, but I couldn’t help but connect with these ancestors fleeing from violence and mistreatment in the South and trying to find refuge in the middle of the country. Many did not see that dream come to pass.

At the same time, I became more acquainted with the shared Afro-Indigenous history prevalent in Oklahoma and beyond. Our communities’ kinship with each other has been intentionally erased by colonial record-keeping. So it became important for me to have the central relationship of the comic reflect that connection.

CK: I grew up in a small town in the South, so I came to learn about the relationship we had with the indigenous peoples who lived on the land before us. But because they weren’t there anymore, we talked about them like long-deceased friends or more weirdly, that they had become subsumed into us. Reading Darlin’ was like peeking into what used to be.

OS: Yeah! I’ve been thinking a lot about how much of that history is mythologized within Black families specifically because those family ties have been stolen from us by the colonial record and disenrollment. It’s been healing to listen to Afro-Indigenous folks and their family stories. Our connection was never truly severed. And it can be reclaimed.

CK: But to backtrack a bit, you mentioned that the Exoduster movement coincided with the wolf extermination, which gets me thinking about your relationship to wolves and werewolves as an author. Why wolves? Why draw the metaphor?

OS: I started researching wolves in 2018 when I worked on my middle-grade werewolf graphic novel, Artie and the Wolf Moon. When I saw how actual wolves have been completely lost within the mythology, fear, and misconceptions built up around them, I couldn’t help but relate. I felt a deep empathetic connection to the plight of wolves and to the charged language and violence thrust upon them in the United States. Through a werewolf story, I’ve wanted to sit with these very familiar ways that wolves here have been villainized, exploited, scapegoated, and forced into an archetype that they don’t actually fit. Wolves have been characterized by American settlers as violent, cunning, too stupid to live, devilish, cowardly, strong, weak, vicious, and lazy. These contradictory narratives fluctuate to preserve the idea of (white) men’s supremacy over them and over nature. I’m relating to this familiar story from my perspective as a queer Black American woman, but this ideology extends into the fabric of Manifest Destiny, of colonialism and the genocide/displacement of Indigenous peoples here, and to various marginalized groups in America.

So writing this story about a Black person and an Indigenous person choosing to be wolves, it’s not about dehumanization, or denigrating myself by drawing a comparison to animals. All humans are animals. There’s never been anything wrong with being an animal, only with how humans have been conditioned to fear, abuse, and exploit other species for our gain and to feel superior. We separate ourselves from the ecosystem that supports us so that we no longer have a responsibility to reciprocate its gifts. By choosing a life in the bodies of wolves, my characters are very literally rejecting the rigid, selective definition of humanity that white supremacy offers us on a conditional basis and that it just as easily withdraws when we no longer serve it. They’ve removed themselves from participating to the most extreme degree.

CK: Yeah, the metaphor almost writes itself when you put it that way. This reminds me — looking back at 2018, that was a huge time socio-politically — we came off a huge swell of protests, televised injustice, a turn to more blatant vicious rhetoric about the marginalized in the news, and a collective turning inward after allies let us down and institutions offered us less protection. Thinking about how your reference mirrors that time period and today, it makes sense why your characters would choose to remove themselves from those systems.

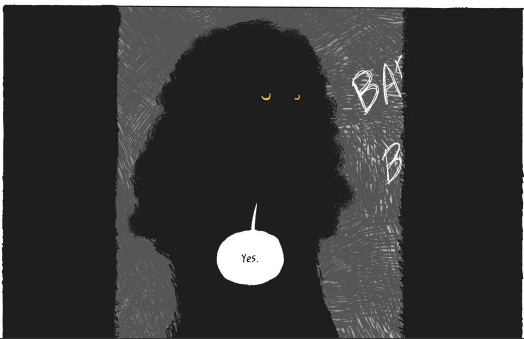

CK: Let’s talk about actually making the work real quick—your lines feel nimbler and your colors concrete and definite. Did your process shift at all from your previous work during the making of Darlin’?

OS: Every part of my process changed, but in ways that made the work more comfortable for me. My debut graphic novel was a 250-page book in full digital color, and I inked the book traditionally with brush and pen on 11×17 inch Bristol. It was a huge undertaking because of the size of the paper I’d chosen and because I don’t like working in full color. I prefer to work in black and white with some spot coloring for emphasis.

At some point, I started trying out fountain pens in my free time and knew that I’d found an inking tool that benefits my sensibilities better than brushes ever could. So for Darlin’, I switched to inking on 9×12 inch paper with a fountain pen. I digitally tone the pages in greyscale and I also incorporate pen and ink textures that I scan in alongside them. This process feels the most natural to me. I don’t think I could make a comic that’s 100% traditional or 100% digital. The synthesis is important. And because this process is comfortable for me to work in, I felt a lot more confident in experimenting with the imagery and page layouts.

CK: That synthesis makes a huge difference! While you can get rougher textures from working pure traditional and precision from digital, seeing you marry the two the way you have heightens that grittiness in a way that feels intentional and potent for the whole story.

That said, you just came off another residency during this interview! Tell me a little bit about what you were there for and what you wanted to accomplish—if anything,

OS: Yes! I’ve done several different artist residencies since I graduated from art school. The typical residency I attend provides free lodging, meals, and workspace, and is generally located in a quiet, meditative environment. Darlin’ would simply not be possible as a side project without the quiet time and space provided by residencies like Storyknife. I arrived at Storyknife with only one real goal in mind, which was to put a dent in the readings and historical research that I’d gathered so that I can confidently move forward with the next piece of the comic. Luckily, I’ve returned with the loose outline for Part 2 written, as well.

But more than that, an artist residency is a place to nurture my creativity, away from any frameworks of monetization or contractual obligation. It’s a place for my heart’s work; a place to think for extended periods without interruption. That last thing is harder and harder for me to find. That’s why I apply.

CK: I think this is what separates you from a lot of artists I know working today. You seek out the spaces that allow you to make the best work possible. I think that quality is rare among artists: the ability to shape your life around the work instead of the opposite—shaping your work around the life you live

I can imagine this is something you’re not looking to settle out of any time soon. Does this affect your ability to feel settled or grounded as a person? Or does this kind of nomadism give you that grounding?

OS: These are questions I’m still trying to answer for myself. In many ways, I feel that it’s impossible to contort myself into the rigid structures and expectations of modern America. I don’t drive, I don’t work jobs with set hours, or healthcare. I don’t want kids. I don’t desire a romantic partner. I move around a lot and rely on the spare rooms of friends and family. Part of me is tired of it. I don’t recommend living this way. With all of that “nomadic artist freedom” comes extreme financial precarity. Another part recognizes that outside of being independently wealthy, this is the only way of living that allows me to do the work without any compromises. It’s profoundly selfish! But the work means too much. I’d be miserable otherwise.

CK: I feel you, this sort of life does go against a lot of different grains and is hard to reconcile with or recommend to others. But if you weren’t living that life, you would be making the stories you’re making.

I guess that leads me to something like a conclusion here: what’s next? I feel like the past few years has made the idea of a “future” or “career” abstract to a lot of us, but I’m curious—in a perfect world for Olivia Stephens, what are you doing in it?

OS: In a perfect world, I’m mostly doing what I am now. I’m happy and I’m dedicated to making Darlin’ and other comics; making my heart’s work. I’m not a young, hungry graduate chasing down opportunities or acclaim anymore. I’m letting those things come to me.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply