Balancing fear and comedy when telling a children’s story is a highwire act and Mizuki Shigeru was a sure-footed master of the craft.

The Birth of Kitarō is a collection of stories by Mizuki featuring his most enduring character, Kitarō. Part of an eight-volume series published by Drawn & Quarterly, The Birth of Kitarō features seven stories published between March 1966 and December 1968 (translated here by Zack Davisson).

Mizuki’s tales of Kitarō revolve around the titular protagonist, a half-yōkai child, his adventures, and his interactions with and against other yōkai. Yōkai is a general term for Japanese folkloric characters: ghosts, spirits, tricksters, demons, and other supernatural beings or phenomena.

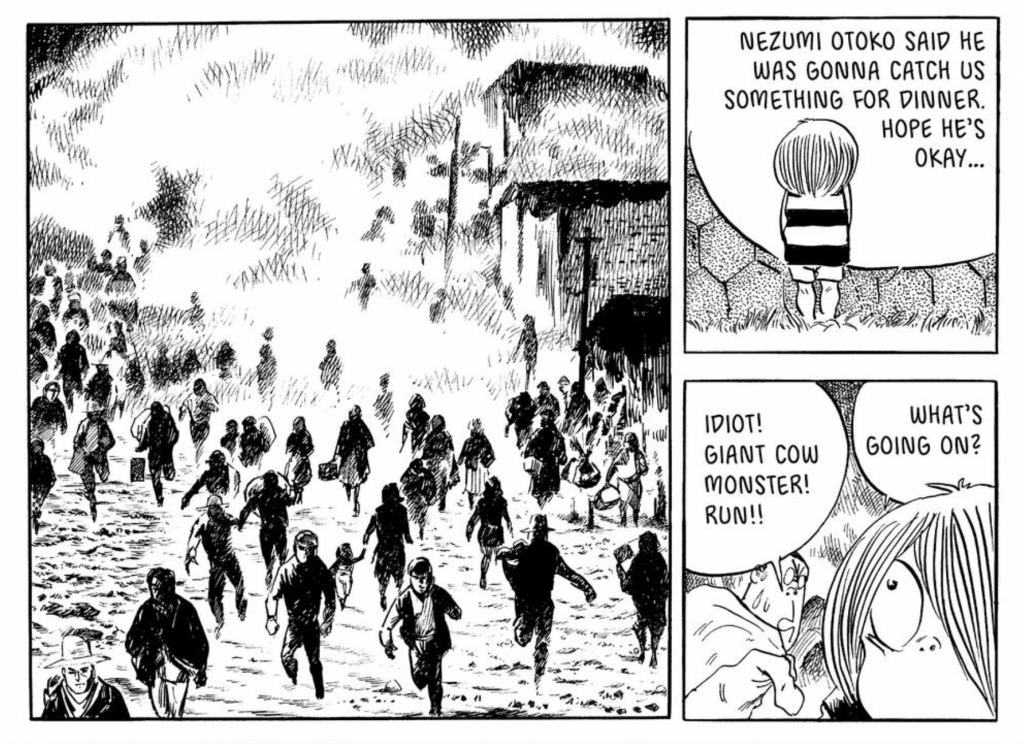

Mizuki’s depictions of yōkai are suitably scary for a children’s book and Kitarō’s foil, Nezumi Otoko, is a comically greedy ne’er-do-well who balances the tone of the series. Kitarō’s character is flexible enough to be comedic when necessary, and unflappably cool at all other times.

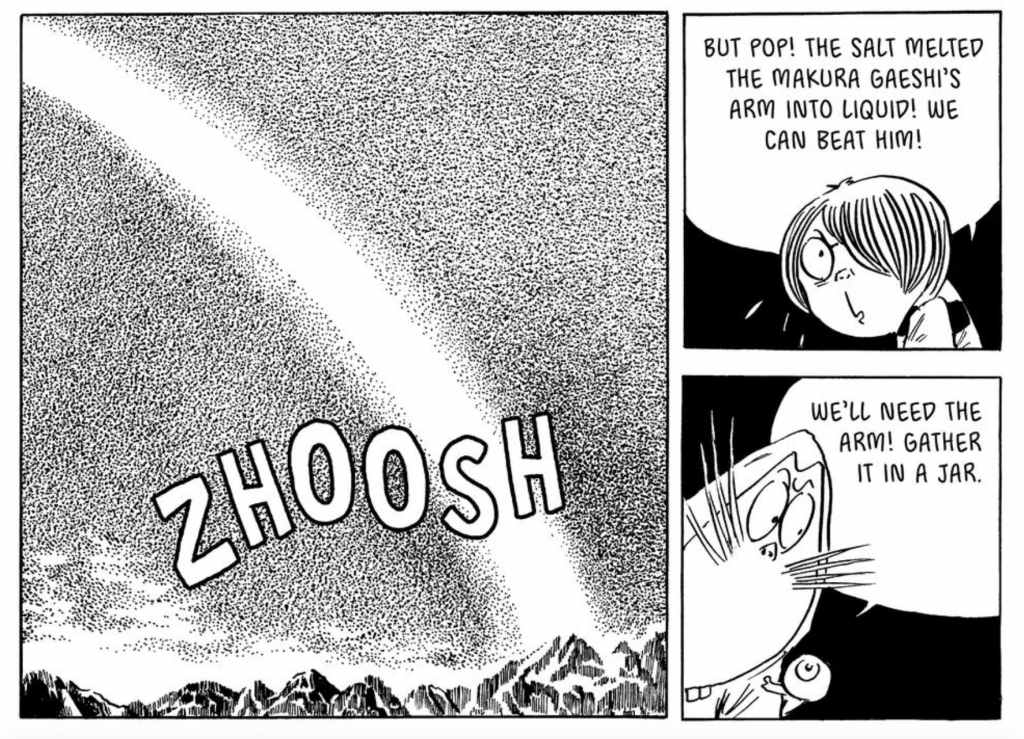

The yōkai in Kitarō are based on folklore and filtered through Mizuki’s imagination, to suit the needs of his tales. Some yōkai are conceptually terrifying, given that this is a manga for kids, and in cases like Nopperabō the face-stealer who eats human souls, Mizuki tempers the fear with loose, cartoony linework (and the souls are deep fried in tempura batter). To ground the more fantastical yōkai, like Nozuchi, an enormous snake-like being that vacuums up life energy, Mizuki draws them in a realist mode.

Kitarō’s parents are the last survivors of the once world-spanning Yurei Zoku (which Davisson translates as Ghost Tribe). Following their decimation at the hands of humans, the Ghost Tribe hides in the shadows of the world, in broken, rotting places, until they are all but extinct.

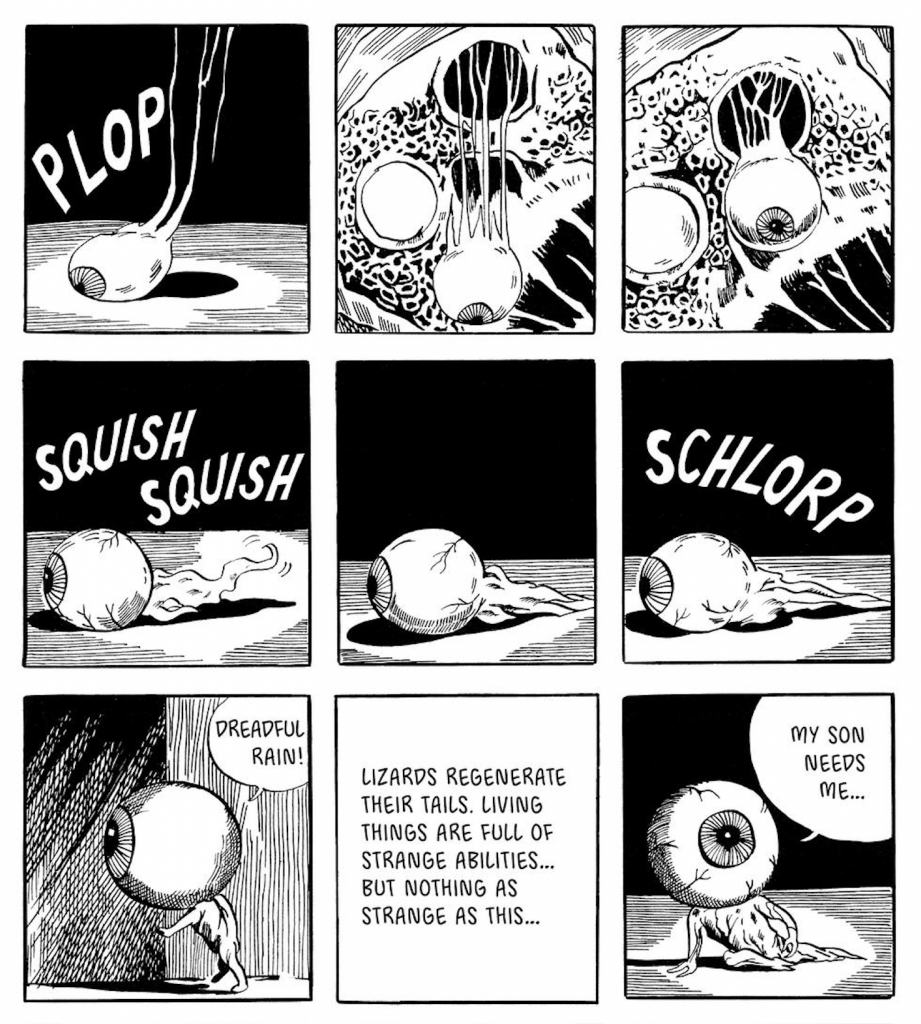

It’s unclear what sort of yōkai Kitarō’s thoughtful mother Iwako is, but his father looks a lot like the quintessential Hollywood mummy, complete with fraying bandages and rotting flesh (presumably this means he was once human). Following the deaths of Kitarō’s parents, Kitarō becomes the last of the people, although Mizuki gives this sad state of affairs a lovely twist – even in death, Kitarō’s father remains a caring dad, as his spirit comes to inhabit the left eyeball of his own corpse. This eyeball promptly sprouts a body and takes to wandering the world with Kitarō. Mizuki uses this new character, Medama-Oyaji (Eyeball-Dad) as a guide to the yōkai Kitarō meets. It’s weird, it’s macabre, it’s charming.

The orphaned half-yōkai child is adopted by a kindly human couple who raise him until he leaves home to explore the world. Visually Mizuki crafts a human-looking boy with a missing left eye, kept hidden by what we now think of as an Emo haircut. Kitarō’s hair has supernatural powers as do the geta (wooden footwear) he inherits from his birth parents. He also possesses what may well be the first frighteningly long, prehensile tongue portrayed in comics.

***

Kitarō’s world is one inhabited by all manner of folkloric beings. In this, Mizuki has an almost endless collection of ghosts, goblins, spooks, and weirdos to tell stories about. His work on Kitarō relies on a fine balance between goofy cartoon characters inhabiting a sinister, realistic world. Mizuki’s backgrounds are lush, detailed, and evocative. What sets his work apart from most other mangaka is how frequently such backgrounds appear in any given story. The modern tendency is to use these detailed, realistic backgrounds sparingly – they appear in large panels, full-page panels, or double-page spreads. Often, they serve to establish a location or to make a dramatic point. Mizuki, however, uses them in small panels and frequently. And when the reader is regularly reminded of how real the world is, the macabre events and characters become pervasively eerie. Contributing to this is the fact that he rarely uses empty backgrounds. Mizuki makes full use of cross-hatching, stippling, and other tools to create space and volume in the backgrounds. He also frequently uses a solid black fill to occupy a background, creating a sense of mild claustrophobia in the pages – a useful atmosphere if you’re telling ghost stories.

Mizuki juxtaposes two kinds of line in Kitarō to denote two opposing atmospheres. As above, the line he uses for backgrounds and many of the yōkai is in a realist mode (ensuring the young reader associates yōkai as part of the real). However, he deploys a looser, more cartoony line for his characters and the funnier of the yōkai like Nezumi Otoko, Neko Musume, and Nopperabō. Notably, Kitarō’s parents are drawn in the realist mode, establishing the manga’s horror credentials right away in the first story.

Given how gifted an artist Mizuki was, there is an oddness to his depiction of human faces – certainly in the first story in this volume, dating from 1966. It’s not that the 1966 manga was the first time he had attempted a realistic human face in the series – Kitarō had run for six years by that point. But the sheer inconsistency between panels in the depiction of the human protagonist in that story borders on the intentional. An attempt at creating an unsettling atmosphere, perhaps? The character, a businessman named Mizuki, is drawn in a semi-realist style. Mizuki the mangaka appears to have abandoned this approach in later stories, where human characters are depicted in the style of cartooning he uses for his main characters.

As for page design and grids, Mizuki doesn’t seem interested in making an art of these. His pages and grids are tools solely focused on conveying story. His default is a 12 x12 grid and his pages use the smallest square frequently. This results in lots of story per page and a tendency in the reader to pull the book close, to really step into the worlds Mizuki creates – exactly what a mangaka might hope for if he’s telling a horror story.

Kitarō series stands as a major work, one that occupied nearly a decade of Mizuki’s career. In addition to its undeniable entertainment value, the manga introduced a generation of children to the folklore of Japan. As the character lives on in Drawn & Quarterly’s edition, maybe it will show a whole new generation that you can be an outsider and still create a life for yourself, while helping others along the way.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply