In my capacity as a freelance editor, I often talk about the three primary aspects of story structure: world-building, plot, and character. Of the three, I regard world-building to be the least important; it adds flavor and variety to your story. Plot gives shape and structure, but it’s your characters who bring the story to life and make it memorable.

Sometimes, genre stories can devolve into formulaic exercises that are more about an author dreaming up some big fantasy world, or a writer thinking of clever plot twists. If the characters themselves aren’t sharply defined and given interesting motivations, such stories become instantly-forgettable exercises.

Audra Stang is an interesting cartoonist because she’s chosen to go all-in with a series of stories (set twenty years apart) taking place in a seedy, decaying Southern tourist trap town. It’s the kind of town that doesn’t really have its own industry other than tourism, and so a certain kind of desperation can set in when the tourists stop coming. However, living in a tourist town is also highly destabilizing as a native, as your very livelihood depends on the presence of people you don’t necessarily want around.

In her one-woman anthology minicomics series, The Audra Show, and other odds and ends like Star Valley Stories, Stang establishes Star Valley as this kind of strange, transient place where weird and sometimes even magical things can happen. From the very first issue of The Audra Show and the introduction of its protagonist, Owen Minnow, Stang establishes a fabulist bent to her stories. From the very beginning, there’s a linear narrative that can be followed, but Stang also jumps back and forth in time, creating gaps in the story. Like reading Jaime Hernandez’s “Locas” stories or perhaps more accurately Gilbert Hernandez’s “Palomar,” these lacunae add intrigue to the overall narrative. A hint here, a clue there, a look at twenty years or more into the future or past all allow Stang to use gaps in the plot and character development as an essential element of her world-building. Like with Palomar, the strangeness of the environment has a profound effect on all of the characters, especially when some wild cards are introduced.

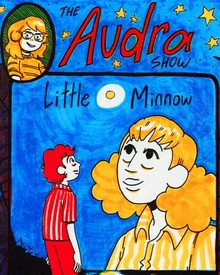

The first issue feels like a classic 90s slice-of-life comic, as Owen Minnow and Bea Allen work at a local tourist trap restaurant called Jelly’s. Everything in town touches on this touristy faux-marine theme. There’s a sly reference to Dan Clowes’ Ghost World in the opening scene, as a nerdy Owen is mocked by a couple of teenage girls who make fake sexual advances. Stang uses a lot of primary colors here that give the comic a sense of being almost an artifact, like something you’d find in the back of one of Frank Santoro’s boxes at a convention. Set in 1988, Owen and Bea dance around a mutual attraction (and a highly annoying coworker who makes sexually inappropriate comments to Owen about Bea) until they end their shift. Curious, Bea follows him to the docks, and when he jumps into the water and doesn’t emerge, she jumps in to save him. Not only is he fine, but he reveals to her that he somehow gave himself gills. While this development completely alters the reader’s understanding of the story, it’s actually more significant as a character moment, because here is where Owen finds the courage to ask her out.

The back cover highlights the sheer delight Stang takes in being the ruler of this little universe. Just as we see her image on the front cover corner box, so too do we see her on the back cover, as tantalizing scenes are shown from 1983 and an older Owen from 2008. It’s a remarkable debut for a series.

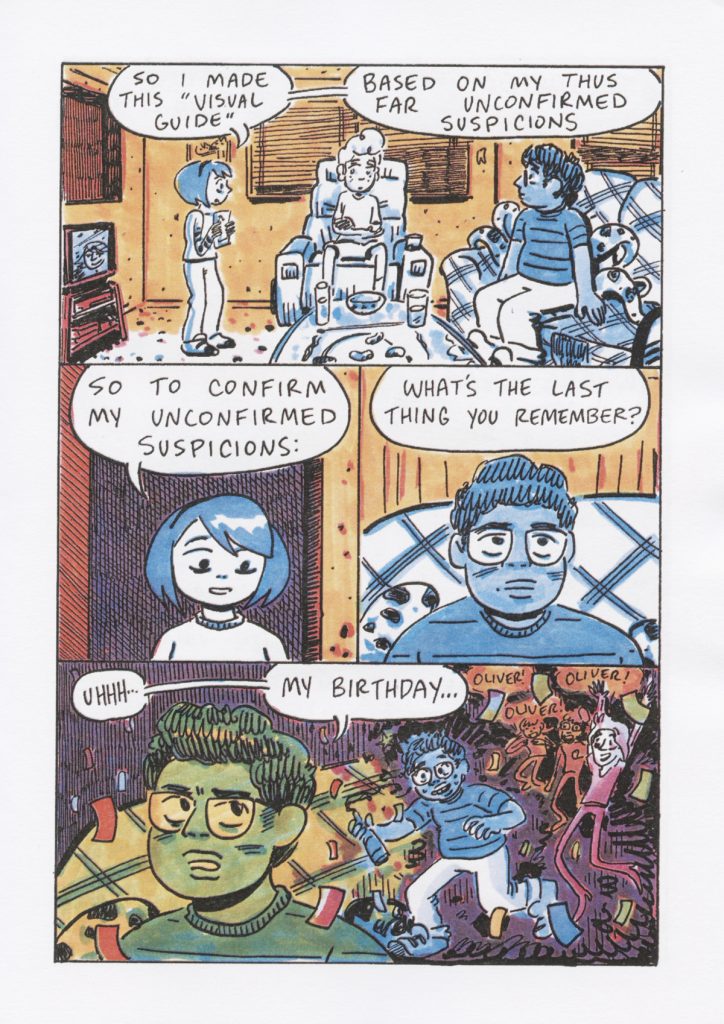

Still using that same color scheme, heavy on reds, yellows, and oranges, the second issue abandons all of the characters from the first issue and moves forward twenty years. Here, we meet the protagonists of Star Valley in 2008: high schoolers Adelaide Lane (a Stang stand-in of sorts), Bryson Yogurt, and the mysterious musician Oliver Chance. Adelaide is an aspiring cartoonist and full-time troublemaker who has trouble making friends. Bryson is the son of the owner of the Magic Seas theme park, and he’s embarrassed by his go-getting father and obsessed with his inventions. Testing out an “ice ray” that only shoots sparkles, they come across Oliver in a dumpster. A year earlier, Oliver went from obscurity to fame as the lead singer of the pop-punk band Sunset October. When they pull him out of the dumpster, he’s sporting tentacles, like something out of a hacky anime series. The last thing he remembers is playing with his band. Once again, Stang establishes an intriguing and off-beat relationship and then throws in a fabulist, completely unexplained monkey wrench. It never feels random or unearned; rather, there’s a delight in revealing plot details slowly while concentrating on each character’s motivations.

The third issue splits the two timelines. However, the Bea and Owen timeline in 1988 has jumped ahead a few months, as Owen has quit the diner and left town, leaving Bea to figure out what she’s doing with her life. It’s a character spotlight story, as we see how deeply Bea is struggling. Stang has a great sense of panel-to-panel transitions, especially when they are silent in creating story beats. There are a couple of sequences where Bea imagines Owen and her co-worker Flower silently quitting as they are in front of their stone-faced boss.

In 2008, Adelaide is secretly excited to have people over at her house, thinking “That’s so..normal!” As she worries about screwing it up, she naturally makes an inappropriate comment and immediately regrets it. She’s the outsider who desperately wants to belong to something but is so poorly socialized that she has no idea how. Bryson’s motives are a little more opaque, but he’s an outsider of sorts himself. Oliver is simply a mystery, especially with his memory loss and tentacles, but Adelaide starts to piece it together. Stang may jump around and throw curveballs at her reader, but she plays by the narrative rules she established, and a patient reader can see the plot unfold in each successive issue. Still, the plot is less important than this push-and-pull of alienation of her characters and their need to be part of something bigger than themselves.

The fourth issue clears up some mysteries but creates more questions. Oliver reveals that he blacked out after a performance in Star Valley a year earlier, after exploring the mysterious, abandoned tunnels of Magic Waters. Stang gives her series a suddenly Lovecraftian bent, with mysterious ocean creatures, magic, and unexplained events. Meanwhile, Bea and Owen cover some of the same ground, but Owen says he’s coming to town to visit her after selling his goldfish and getting a mysterious new job. Bea is drowning in misery at her job and desperately wants Owen back all the time.

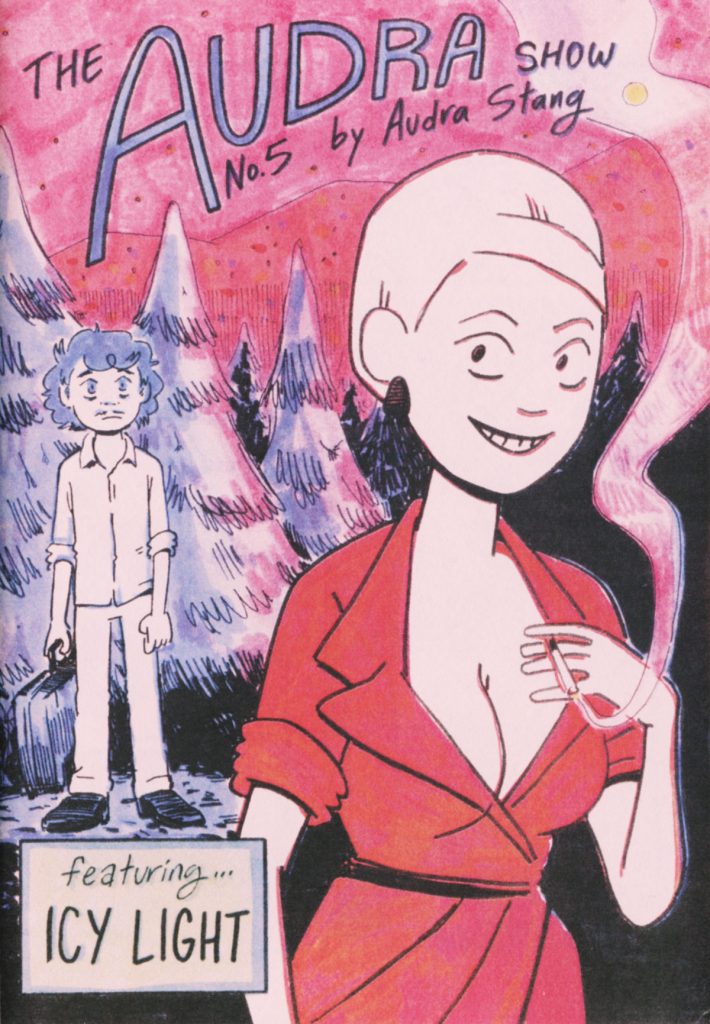

Stang establishes a back-and-forth rhythm between the two timelines and spends a good bit of time introducing the extended protagonists. The fifth issue introduces the disruptive and antagonistic element in the chaotic, seductive, and nihilistic patron Margaux Delmar. She takes an interest in Owen while buying his fish, threatening to steal them. When she learns he has gills, that interest turns into obsession, as she calmly states, “I want to fuck you and kill you,” as though she’s a praying mantis. At dinner, she reveals that she already knows a lot about him and wants to be his patron, giving him a briefcase full of money. The reader then sees the other side of the phone conversation from issue #4, as Owen is not entirely forthcoming about this bizarre woman who gives him a pile of money and declares that she’d jump his bones the minute he and Bea broke up. For Bea’s part, she vocalizes fears that things will be weird with Owen when he comes back, touching on that feeling of fragility with regard to relationships.

The sixth issue is the strongest of the series as a single entity, as Stang just hits her stride in terms of sequencing, going back and forth in time, and providing bizarre interstitial stories. While Owen and Bea both fret about each other wanting to break up and think they are utterly worthless, their eventual reunion has its own problems, as Bea notices the burn on Owen’s hand. Owen continues to be a key character in the interstitial pieces, as one story has Margaux as a vampire, feasting on an enslaved, older Owen who is clearly over all of this. There’s a shift to Owen in 2008, complaining alone in a kitchen to no one in particular. The rest of the issue is a bit of bonding with Adelaide and her friend Bernie (seen in a serial in the excellent Rust Belt anthology), a fantasy sequence where Margaux straps Owen to some fireworks that’s something out of a Road Runner cartoon, and a rare bit of funny memoir from Stang. Stang even includes a letters page, which contributes to its overall feel of a 90s alternative comic. At 28 pages, it’s a dense, satisfying read that continues a couple of different serials in a way that doesn’t feel too beholden to a particular plot.

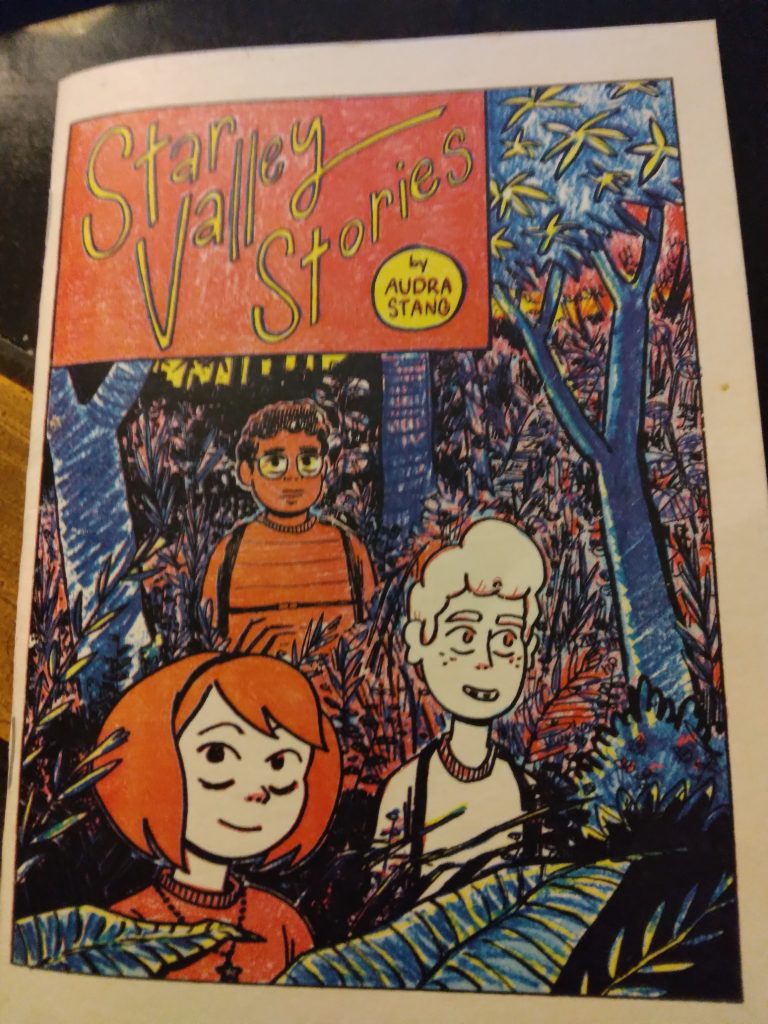

Star Valley Stories acts as a prequel to The Audra Show, as it’s comprised of short stories that originally appeared elsewhere. In fact, Stang refers to it as “The Audra Show pilot” in the notes page. Some of them were minicomics (like “April 2008” and “June 2008”), some were assignments for the Santoro comics course (“The Ice Ray”) and some were made to appear online (“Indigo Rite”). “April 2008” explores the high-school dynamic between Adelaide and Bryson, who express their mutual physical disgust for each other through an intermediary. Of course, it’s obvious that there’s a mutual attraction that they’re not willing to understand. “The Ice Ray” is a variation of the story that appears in The Audra Show, but Bryson’s older sister Marsha is a key character. Bryson and Marsha are united in their antipathy toward their father. Stang’s art in this story is considerably different from their later work, with an awkward mix of naturalism in the grotesque. She eventually settled on a more cartoony style that allowed for a smoother narrative flow.

“Oliver’s Corpus” is a story that hints at his disappearance, as here he wishes to disappear. It also touches on his body-image issues. “Star Valley Pitch” turns the focus on Bryson and his difficult relationship with his dad. “June 2008” establishes the tenuous friendship between Adelaide, Oliver, and Bryson, as they set off bootleg fireworks. It’s a sublime moment for Adelaide, something she chases throughout the series. “Secret Knowledge” intriguingly sets up a friendship between Owen and Adelaide in 2008; this is in black and white, which just doesn’t work quite as well in creating the atmosphere presented in The Audra Show. Finally, “Indigo Rite” touches on Bryson’s personal life and other students at Valley High School, including Clark Kessler, Kelsey Reed, and the spacy Cosima Tom. The story is about Bryson trying to make the track team, Kelsey being intrigued with Bryson’s sister, and Cosima revealing that she’s a witch–the first instance of fabulism being introduced in these stories.

Stang has a knack for depicting the ways in which the status quo can change so quickly for young people. One can almost feel the dust and grime in Adelaide’s living room, as she suddenly has people hanging out for the first time. It’s a total paradigm shift that gives her confidence and joy, even as she struggles with the idea of acceptance and belonging. Owen and Bea are emblematic of drifting twentysomethings looking for a direction and possibly finding it in each other. Stang evokes a sense of wistfulness above all else, a feeling that these connections are fleeting and fragile, even as they feel so important at the time. Some of this is done through her use of color that evokes neon nostalgia, like living in the theme park that is referenced so many times in the series.

What makes The Audra Show so compelling is that Stang clearly has a sweeping, even epic, conception of how this story is going to go. It’s obvious that she’s thought a lot about this strange little town and the importance of over a dozen characters, many of whom haven’t even been introduced in the series proper. The supernatural and science-fiction qualities of the story blend easily with the slice-of-life, slow-paced quality of the narrative, as character development and interaction are the key elements of her story. It’s less important to know that Bryson is an inventor and more important to know that he’s ambivalent toward his father. It’s less important to see that Oliver has tentacles but crucial to understanding his own body-image issues. Owen’s story doesn’t hinge on him having gills so much as it does on him being alienated from his environment, and, ultimately, from humanity in general. The genre elements add intrigue and flavor, but it’s clear that Stang is much more invested in what happens to her characters.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply