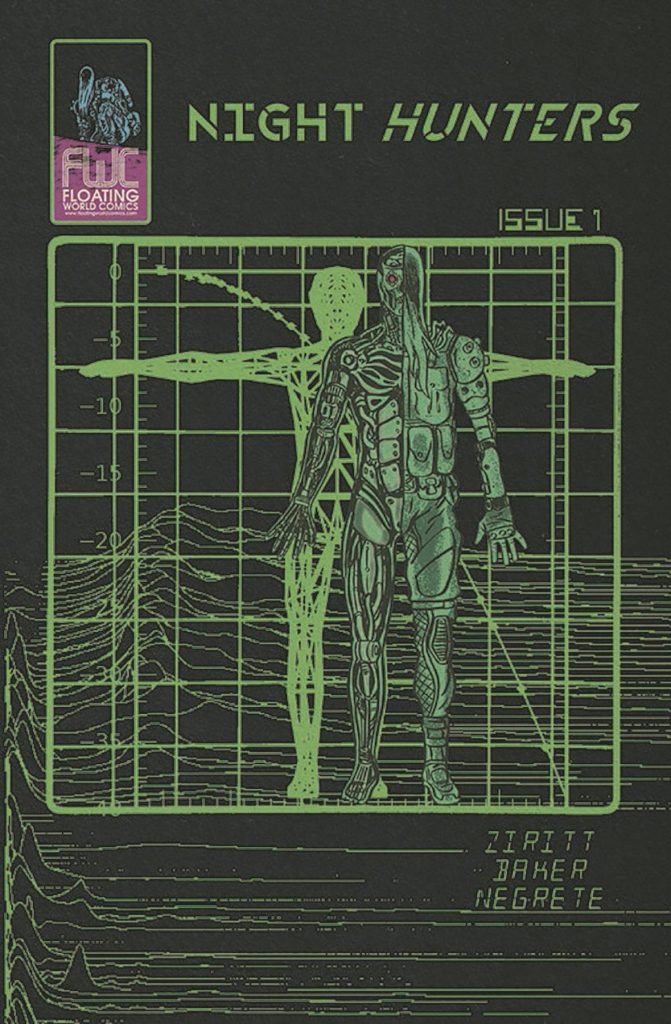

Night Hunters, a four-issue miniseries from Floating World Comics, recently collected into a single volume, is one the rarest beasts in the world of direct market comics – the artist gets credit first. The series is drawn by Alexis Ziritt, written by Dave Baker, and lettered by Robert Negrete. The cult of the writer has long since taken over the discourse in this little corner of comics, with the artist(s) often seen as nothing but the executors of the writer’s will; not so here. And if you ask why, it is enough to open the comic and see the first page. Of course, Alexis Ziritt gets the credit first, Alexis Zirittt should always get the credit first; possibly even in comics he’s not involved with.

Ziritt broke into public consciousness with the science fiction action series Space Riders (written by Fabian Rangel Jr.) and continues to work on its sequels, as well as the graphic novel Tarantula (also with Rangel Jr.). His style is immediately identifiable – neon-lit moodiness pulsating over pencils of heightened brutality: the bastard child of heavy metal concert posters and the urban degradation aesthetic of Canon Films. If the Death Wish series would have been allowed to continue into the 21st century it would probably look a bit like Night Hunters.

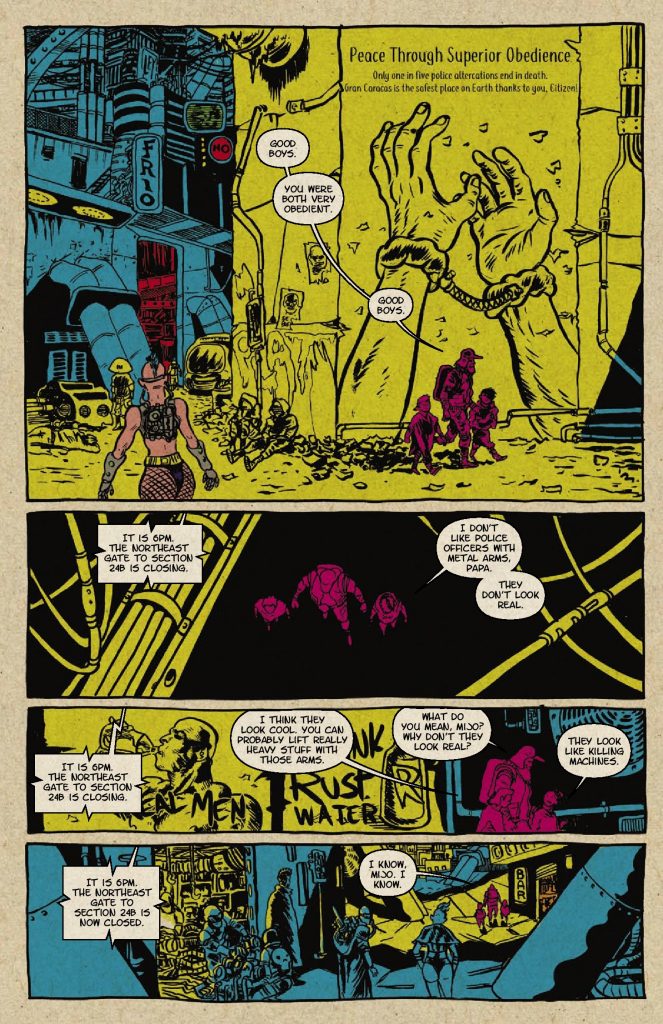

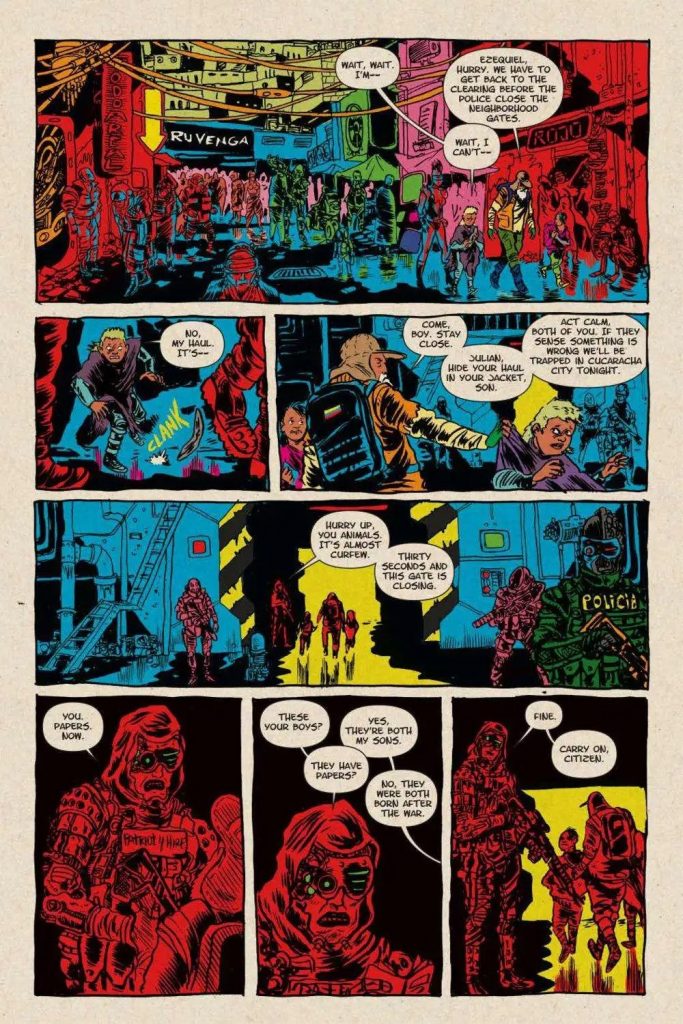

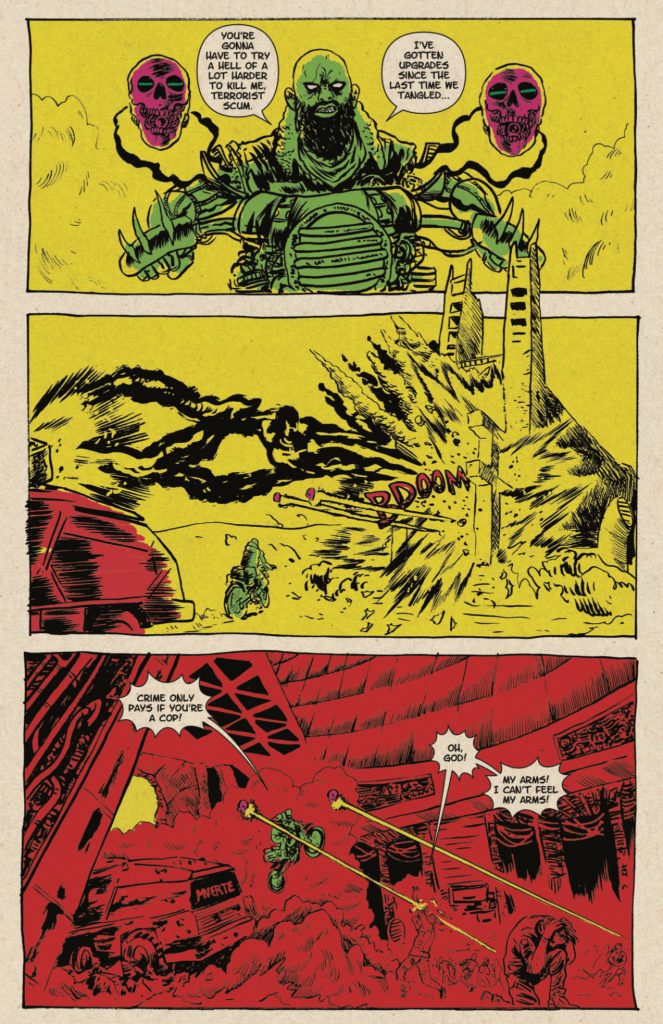

Zirittt colors his own work because colors are such a strong part of the process. Like the great colorists of the 1980s (Julia Lacquement, Tatjana Wood, Adrienne Roy), Ziritt rejects any attempt at “realism” in favor of choices that always enhance and reflect the psychological mood of the characters and the sociological mood of the environment – yellows and reds and greens, strobing like you’re in the middle of a techno concert.

Of course, heightened-cartoonish brutality with an a-realistic color palette is nothing new in comics. Benjamin Mara has made a career of it and, going farther back, one can certainly see the roots stretching to the work of Spain Rodriguez. The big difference (and it is big) is that folks like Mara always appear to draw their action from a safe distance, defended by a wall of irony. They’re depicting the action and mocking it at the same time, allowing the reader to feel above the fracas. Ziritt’s work doesn’t have that ironic distancing to it.

When he depicts massive battles and skull ships in Space Riders, you feel like he’s enjoying it; when the scantily-clad heroine of Tarantula wields her whip to smite at evil, he draws it like it’s the coolest thing ever with absolutely no inhibitions. These books have a very black & white, good & evil binary thinking to them, which compliments the art perfectly. Night Hunters tries to be something else, though, something more complicated and morally grey, which is exactly where the series hits a wall.

The action of Night Hunters takes place in the near future, the second half of the 21st century, in Venezuela. The country had become an authoritarian hell-hole with militaristic police forces that murder citizens without much care (“crime only pays if you’re a cop” is an oft-repeated refrain). Brothers Julian and Ezequiel barely eke out a living with their father in the poor(er) district. When the family gets caught in a firefight, they become separated: Ezequiel is missing, presumed dead, and Julian becomes so wounded the father is forced to beg for the cyborg treatment. This is an expensive treatment (with planned obsolescence for the parts), and one that would force his son to find a more lucrative career than scavenging.

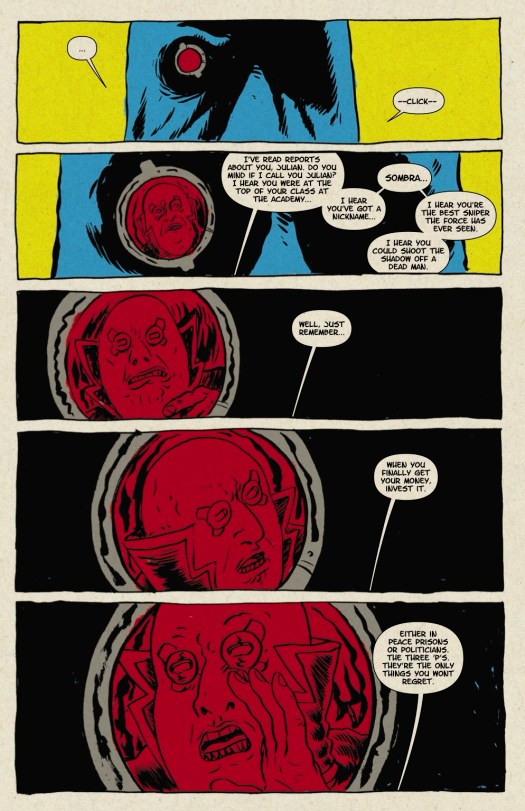

Years pass, Julian is now a top sniper-assassin for the armed forces, part of the titular elite unite, while the still-living Ezequiel is revealed to be the powerful drug-dealer Junkboy, with his own radical agenda for Venezuela. Naturally, the two brothers cross paths again, and personal combat becomes a microcosm of the national one as various agencies and agendas clash for control over resources. The tale itself is not new; in one afterword, Baker explicitly brings up both Robocop and Judge Dredd as examples he strives to emulate (or, at least, as sources of inspiration).

These above-mentioned works gain much of their strength from presenting their stories directly from the point of view of authoritarian forces, while remaining skeptical, or even downright contemptuous, towards their protagonists. It’s a careful balancing act, creating a protagonist that the readers/viewers care for while making them understand the system this protagonist serves is destructive. The famous ending of Robocop, in which the cyborg hero asserts his humanity in front of his corporate overlords, is undermined by the knowledge that these corporate overlords are still in power; that asserting one’s independence is a rather small gesture when stacked against the oppressive power of the system.

With its split narrative, one half of the story follows Julian while the other follows Ezequiel, Night Hunters doesn’t leave us much space to wonder about the nature of the system: the cops are corrupt and evil, they’re the empire from Star Wars borne through the lenses of Radley Balko’s Rise of the Warrior Cop. This, of course, is fine; if nothing else, the last few years have shown the need for stories in which the police are unambiguous villains, except the story here tries to pretend it’s telling something far more complex than what it is.

There are CIA agents involved, and clashes within the governmental forces, and some of the rebels may have their own hidden agendas and willingness to use underhanded tactics… but, in the end, this has the same feeling of a good rebels vs. evil empire fairytale you can find in something like Star Wars. Such a story certainly has its place, and is worthwhile on its own, but all the political machinations and factions backstabbing one another do not really add much to Night Hunters’ attempt at moral ambiguity.

This is the major problem with Ziritt’s work in this series. Sure, there are some minor issues — sometimes the chaos of the pages overwhelms the action to such a degree its legitimately hard to tell who’s shooting at who, the strong colors don’t always follow any identifiable pattern (sometimes yellow is for impact, sometimes pink) — but these are but quibbles. The fact is Ziritt’s default mode of storytelling is “cool”.

When one of the night hunters reveals two drones popping from his shoulders that slice enemies with lasers, it’s cool. When Julian, now identified as Sombra, snipes enemies limbs like he’s high scoring on Call of Duty, it’s cool. When a group of derelicts chop down a bunch of cops with machetes, it’s cool. When someone spits fire from their mouth like a canon, it’s super freaking cool. It’s all cool, every last part of it. It’s so cool that it’s hard to take it seriously when the story focuses for a few panels on the aftermath of a group of invading cops shooting some kids; letting both readers and characters absorb the implications of what they have just seen. It’s meant to be a swift change in the mood, but the cops were already presented in such an over-the-top manner that it’s just weird to think they would care.

What’s more, after this short vignette, the story continues apace with the betrayals and the ultra-violence. You’d think that this moment would be an opportunity for a longer pause or an opportunity for reflection, but no.

As the plot draws to a close, the two brothers are brought into a full ideological clash. In his afterword, Baker claims he sees theirs as a struggle between pragmatism and idealism; except it’s hard to see it in this manner. Julian isn’t a pragmatist, he isn’t much of anything personality-wise. Ezequiel isn’t some unmoored idealist, every choice he makes appears very calculated, even if his aim is bigger than his ability. And, because the government throughout the story is so evil, whatever choices he makes to fight them seems justified. There seems to be something missing in the story; there isn’t much of a sense of the citizenry beyond those already involved in the fight (on either side). What do other citizens feel about Ezequiel’s group? We don’t know. Again, this has the sense of a fable to it rather than a political commentary through the lens of fiction.

Night Hunters is fun to look at; it’s fun to read overall even. Baker has an ear for good shout-y dialogue (“Death by an iron hand is no death at all!”) and the whole thing flows rather well. But this is not Robocop, this is not Judge Dredd (at least, not the good bits of it). What it is, is a comic book that’s too cool for its own good. Night Hunters is great fun to read, moving on with righteous energy and carried on the back of Zirrit’s impressive style. But, sometimes, being fun isn’t enough. If a story wants to make a gesture at political storytelling, it should offer something more than cool explosions. Night Hunters seems to be more invested in the various ways its technological constructs can kill people than in the way people ought to live.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply