Several weeks ago I started the process of creating my editorial cartoon for the Port Townsend Leader with a question: Can a No-Knock warrant be served in the Victorian seaside town I live in? I asked a few lawyers I knew, then eventually ended up on the phone with the sheriff who used to head up an inter-county drug task force. I discovered that No-Knock warrants are allowed on a state level, and I had a long conversation about when they are used and who makes the decisions to use them. He ended the conversation with the reminder that it’s us, the taxpayers, who vote for the sheriffs and judges who issue warrants, and if they make a decision they don’t like, then it’s up to us to vote them out.

As an editorial cartoonist, it’s my job to take something that seems very complex and break it down to be both simple and a starting point for a discussion in my community.

When I started working for my small-town paper, I felt like I was joining other cartoonists across the country in their profession. As I would take notes in editorial meetings and interview city council members and county sheriffs, I assumed that there were hundreds more like me, churning their notes into comics designed to make local politics easier to understand.

I didn’t realize I had actually stepped into a dying profession.

When I searched for other editorial cartoonists that were focused on local issues and invested in community dialog, I kept coming up empty. Instead, I found one-panel gag jokes about President Trump and other national figures. Why were cartoonists like me disappearing? Was anything replacing them? And, if not, does it matter?

I asked friends across the country to put me in touch with the editorial cartoonist at their local papers, and discovered that one of the major problems with finding more small-town cartoonists is that local papers are rapidly disappearing. It’s expensive to print and distribute a paper in an era when most people reach for their phones when they want the news. Why would you pay for a paper when you’re able to instantly know what’s happening in the world for free? I managed to connect with a few cartoonists from a variety of different editorial outlets and get their take on why their jobs matter, and what the future might look like now that those small papers are disappearing, and, with them, an outlet for their comics.

“I think there’s a huge need for more local coverage. News kind of bubbled up into this top-heavy thing that churned out the same national sludge while all the little local papers got bought up or died. I hope the renaissance we’ll see is local non-profit public radio-style models where news is more locally funded and more locally produced,” Pat Race, the cartoonist for Alaska’s political news blog The Midnight Sun, said.

Most local papers are actually operated by larger entities, creating a news outlet that is the exact opposite of the model that Pat Race recommends. Where I live in far western Washington State, Sound Publishing owns the other “local” newspaper, along with 42 others in the Pacific Northwest and Hawaii. To keep their paper profitable they share as much content as they can, including political cartoons which are almost always syndicated.

From an economic perspective, this makes a great deal of sense: the content of syndicated comics is kept general enough to make it applicable to a larger region of newspapers, so they each pay a cartoonist a small amount to run their strip. Though this is logical from a budgeting point of view for both the cartoonist and the paper, a syndicated comic does very little to create a conversation around local political issues.

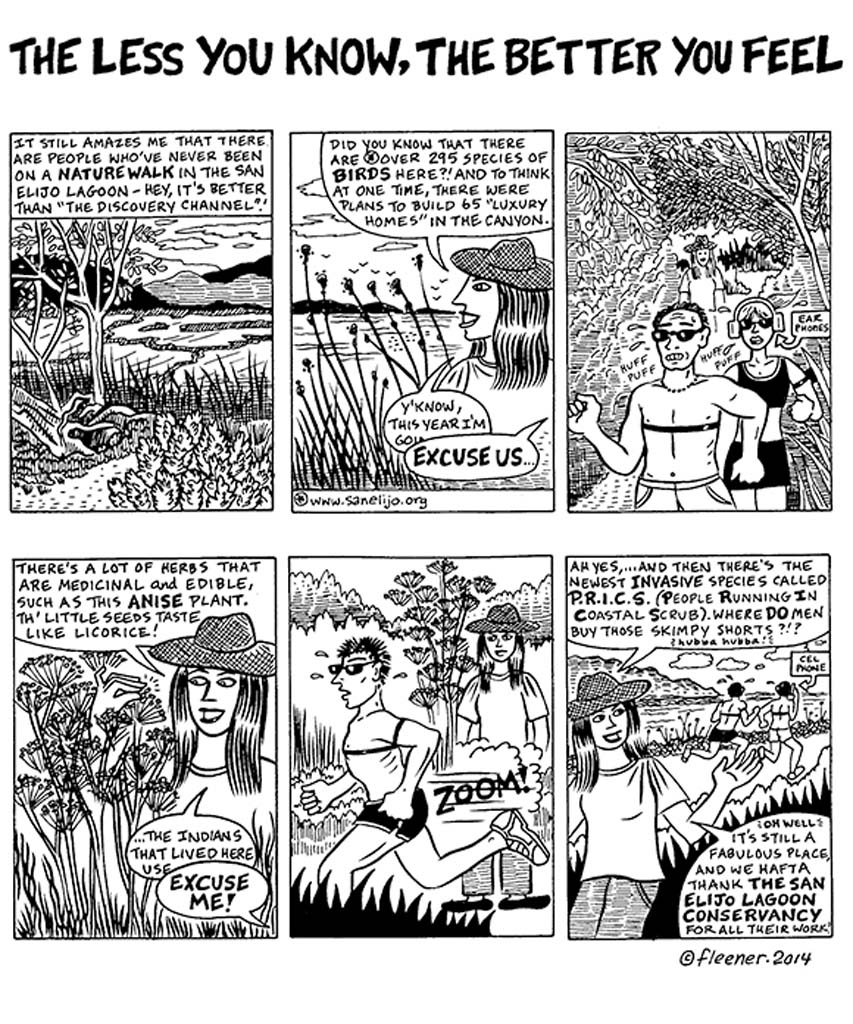

On the other hand, by focusing on local issues you’re often able to create a more meaningful dialog on a national scale. Mary Fleener, the woman behind the underground classic The Less You Know The Better You Feel, discovered that by covering local politics she was able to capture a microcosm of national conversations, especially around gentrification.

She started working for The Coast News out of Encinitas, California, in 2012, though she had already been creating political comics and politically engaging locals for two decades by this time.

Fleener was excited to be given free rein to be as political as she wanted in her work, another thing that is difficult to achieve through syndicated cartooning. The editor mostly left her alone to cover whatever she wanted, but, instead of finding a collaborative environment, she found newspaper people to be weird and competitive and subsequently chose to keep her interactions with them to a minimum.

Pat Race and I have had the opposite experience from Fleener, though. We both work with editors we like, and we’re both included in editorial discussions, which feels like an important part of keeping our job sustainable. “Matt Buxton is my current publisher at The Midnight Sun. He’s a good friend, and I feel lucky to get to work with him,” says Race. “We talk politics a lot, but he doesn’t steer me in any particular direction. He doesn’t exactly say, ‘this is the story I’m writing,’ but I feel like I have a pretty good idea of what’s on his radar.”

Fleener’s comics and mine are both heavily research-based, which both keeps us relevant as a news source and protects us in our communities. If something is a matter of public record, you can only get so mad about it. “The one thing I always made sure of was my facts,” says Fleener. “I did extensive research into anything I was writing about, so there could be no doubt about my authenticity. You may not agree with me, but I was 100% accurate with my facts. If I quoted a council member, it came directly from the video of the meeting.”

Fleener always felt protected by the First Amendment, but the political nature of The Coast News changed after it was sued for libel, another contributing factor to the declining profession of political cartoonist. “Unfortunately, the paper has gone back to vanilla articles and pictures of boy scouts and ballerinas on the cover and the Lion’s Club and all that cutesy stuff,” she said.

Another contributing factor to the decline of newspaper cartoonists is well summed up by Ben Passmore, the author of Your Black Friend and co-creator of Bttm Fdrs. Like Fleener, he burned out on creating political comics for a paper, but less because of editorial pushback and more because he had a hard time feeling like he was making a difference. “The first comics I ever did for a publication was a political comic strip series for my college paper. The vibe was very typical of a college kid learning things about the world adults were already up on. Lot’s of ‘Yo, the structure of our voting system is inherently disenfranchising,’ followed by a TV show reference or something. I did that for most of my time in college, but it felt like pure vanity by the end. For a while after that, I tried to make avid political genre comics. I started a series in 2011 I’m still technically working on called DAYGLOAYHOLE, a post-event comic about gentrification in New Orleans. Doing less literal political comics felt like a way to sneak politics under people’s radar a bit. I actually swore off overtly political comics until I started working for the NIB.”

Passmore likes the immediacy of people’s responses to his work. “I get various kinds of responses from my NIB comics since they’re posted to social media. People will get into my DMs or comments section and give their takes. For whatever reason, the internet is pretty nice to me, no one has ever come for my neck in a big way. I like all of it, though, seeing people’s interpretation of what I make in real-time is mad interesting.”

I also like getting to see how people react to my comics, and how different the reactions are when they’re posted to my newspaper’s facebook page vs when someone has taken the time to write a letter to the editor. I feel like it’s important to the kind of comics that I make that the people responding to them are within the newspaper’s circulation area, but not all cartoonists feel that way.

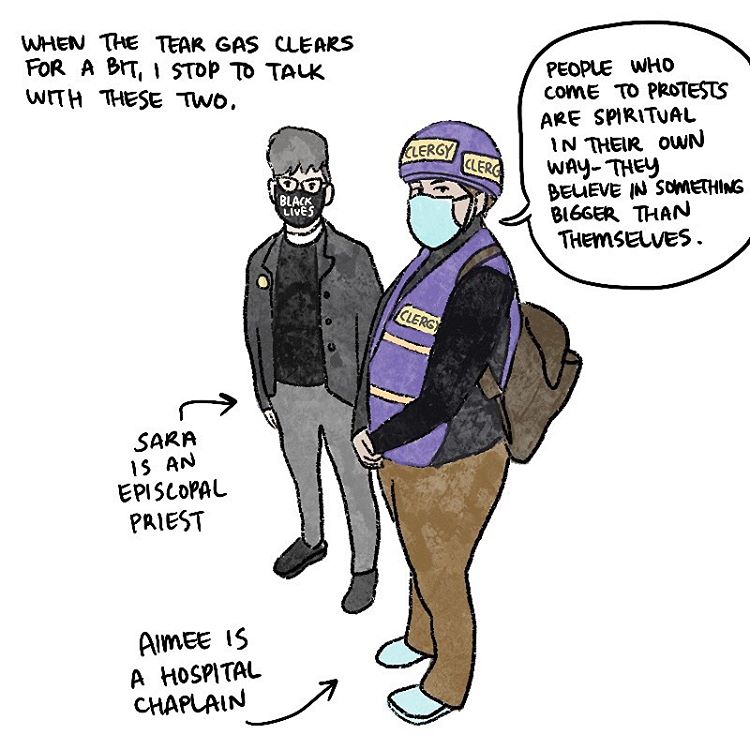

For example, Sarah Mirk, a longtime comic journalist and co-creator of Guantanamo Voices: True Accounts from the World’s Most Infamous Prison, thinks that the connecting power of comics can transcend geographical communities. “Comics really have the power to make the invisible more visible and help people feel empathy and humanity. It is a visual story, you’re seeing another person, you see this place, which makes it more real. Whether you tell a story about prison or yourself and your identity, comics make it more real. They make it possible to have that kind of a deep human connection with somebody”.

Is simply creating human connection enough, though? I feel like one of the things that is important about political cartooning is presenting an issue that asks the reader to re-evaluate how they think, and, in some cases, even change their minds on something they thought they understood. However, many cartoonists don’t think it’s possible to change someone’s mind just with a comic.

Fleener is one of them. She says, “I know the people who are involved and go to council meetings really appreciated my cartoons, but sadly, they make up a very small percentage of the population here that gives a shit. I may have changed some minds when it came to the myth of ‘affordable housing,’ but very few.”

Race also seems unsure, “That’s the big question I struggle with as an artist. What’s the point of any of this? But I come back to the times that I’ve been influenced by art and have to believe that other people can be impacted in the same way. I don’t know how important political cartoons are, but they’ve sure been around for a long time.”

I am relatively new to editorial cartooning, but I’ve already had a reader tell me that I changed her mind about paying city council members a living wage. This felt like a significant victory. I have strong feelings about creating community dialog through editorial cartoons, but I can only create one half of the conversation. I create alone, and hope that I’m able to present an issue in such a way that my audience is able to hear me; to both feel like I’m not attacking them, to be able to understand a new point of view, and to be able to take that into conversations they have with other people.

When you focus on issues instead of ideologies, it’s considerably easier to make a difference. Creating a comic that looks at how police funding is being spent in the context of the types of crime we have, for example, allows people to look at the facts and draw their own conclusion. If, instead, it was a comic that simply attacked the idea of funding the police without any real context, it would be much harder to engage your audience into asking real questions.

Mirk encapsulates this perfectly, “Have I changed anyone’s political identity to be an anarchist? I don’t think so. I don’t focus on that; I focus on sharing a story that expands someone’s understanding of a situation or someone’s understanding of the human experience. Whether I’m sharing my personal experiences, or doing an interview comic, I’ll often hear back from someone saying, ‘I never thought about this before, thanks for sharing that.’”

When my comic on No-Knock warrants came out, I knew I was reaching into many homes who, although they probably knew the name Breonna Taylor, may not have been aware that those warrants could be issued in the place they live. They might not have realized that they, and their neighbors, were making the choice to elect someone who could decide it was reasonable to go into someone’s home without warning when they voted the current sheriff and judge into power.

Do I think that my comic started a movement to change a law? Probably not. But I do think that a lot of people across the political spectrum will be looking harder at who they vote into those offices. And people taking one more factor into consideration before they do something as important as voting makes my job relevant and important. I don’t know if my role at the newspaper will be the future of editorial cartoons, but I do believe that the way comics can be used to break down something complex and important is too useful of a tool to ever disappear.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply