The Fables of Erlking Wood, a folkore graphic novel by writer & artist Juni Ba, opens, following a well-deserved “Goats Flying Press Proudly Presents…”, with a note: “This book is best enjoyed with a cup of warm cocoa.” A perfunctory note at first glance, it is actually an integral part of the book, not via secret plot revelations or grand thematic resonance, but in simply being a table setter. Without this little intro, the story begins too abruptly. Our minds aren’t in the right mode. Our ears (or eyes, as it were) aren’t primed yet. It is an old trick, an ancient trick, and an effective one.

See, this isn’t simply a collection of short stories or a fantasy graphic novel. It’s a fable, a folktale (or group of folktales, as the case may be,) and as such, Ba adopts the role of storyteller. He gathers his audience, inviting us to join him with quiet words and gentle prodding, and asks us to be comfortable and settled. Then, and only then, does he begin, as any good storyteller does, with an introduction.

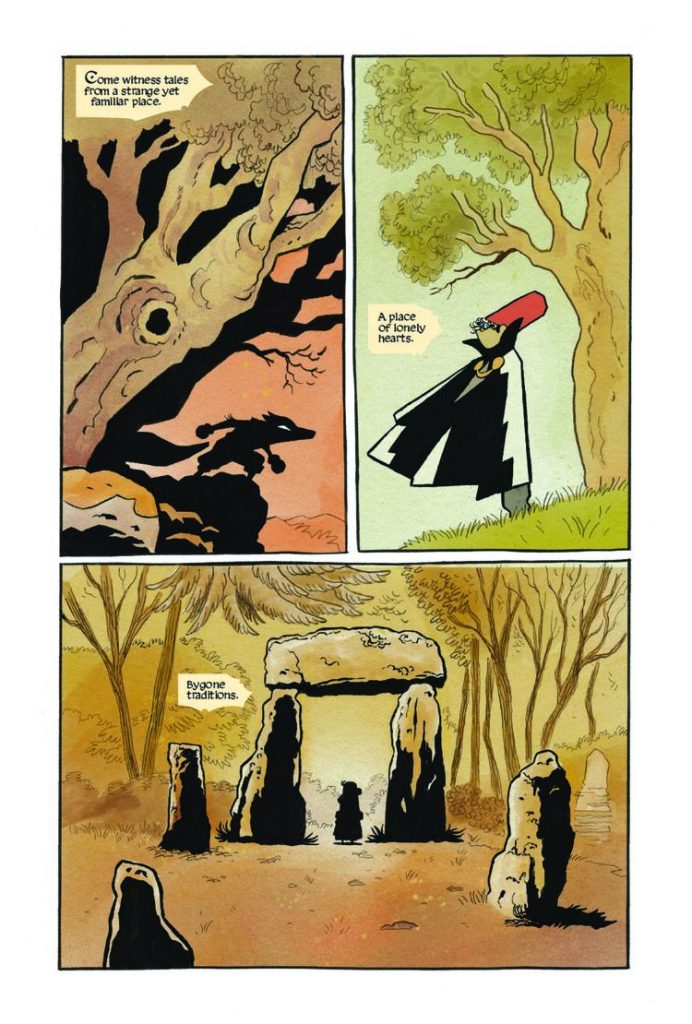

We are told about this book: a collection of stories, twigs, and branches that spring from the tree of Mynislyvix. We are shown icons from the various tales within: a chalice, a gameboy, an orange, a dagger. And we are led through teases of whos and whats and wheres before alighting on our central figure for whom every story revolves around in one way or another: The Erlking.

The Erlking is a striking figure, bathed in harsh reds with gnarled fingers and branched horns. His eyes are yellow slits in the dark of his hood. He stands crouched on a rock, legs bent forwards, the woods tinged orange around him. Foreboding and formidable, this image lingers as we move into the first of the tales.

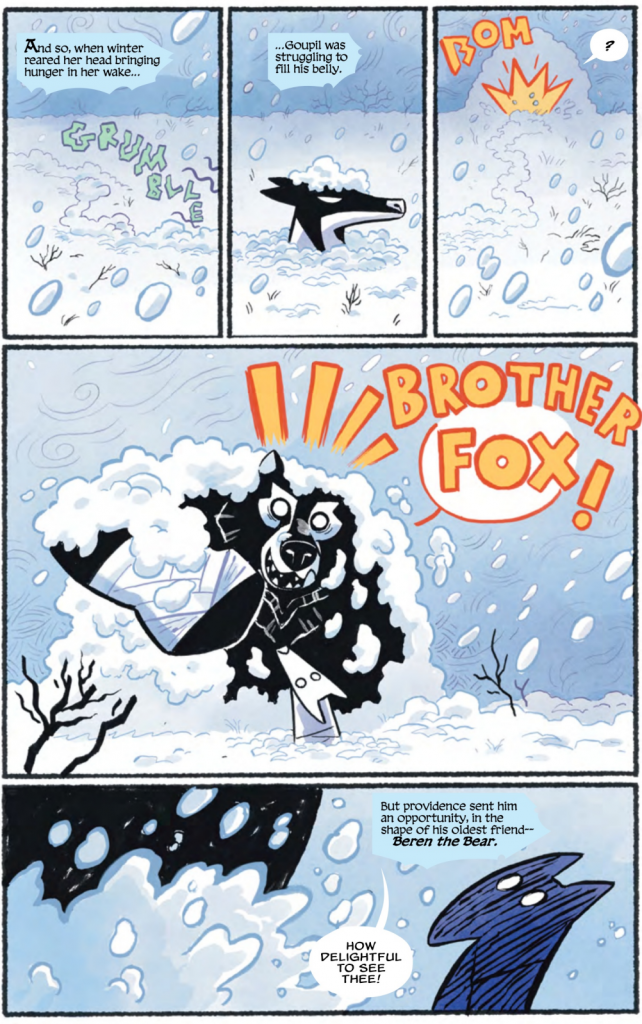

And it’s masterful work; an absolute control of tone that has you in its grasp before you realize it. Like some magic spell, the second your eyes alight on that tree, you must read through, never stopping until the end. Ba then proceeds to illuminate our main trio: Vivianne, who we meet as a child and follow her throughout her life; Goupil the Fox, a trickster and a coward with a reputation to match; and, of course, The Erlking, whose origins and motives begin as a mystery and end in a tragedy. They are good archetypes to follow, and even better characters to learn about.

Part of what makes “The Fable of Erlking Wood” stand out in our current, quite saturated market is that it feels old and weathered, though kept alive and current through Ba’s inimitable style and Bidikar’s restrained yet boundless lettering. I am in awe, as always, with Bidikar’s ability to sink into the page, matching whatever artists he’s working with but never subsumed, never rendered invisible. Were many of the sound effects not in French – gloups, maaaw, pof – I would never have known one was Ba and the other was Bidikar.

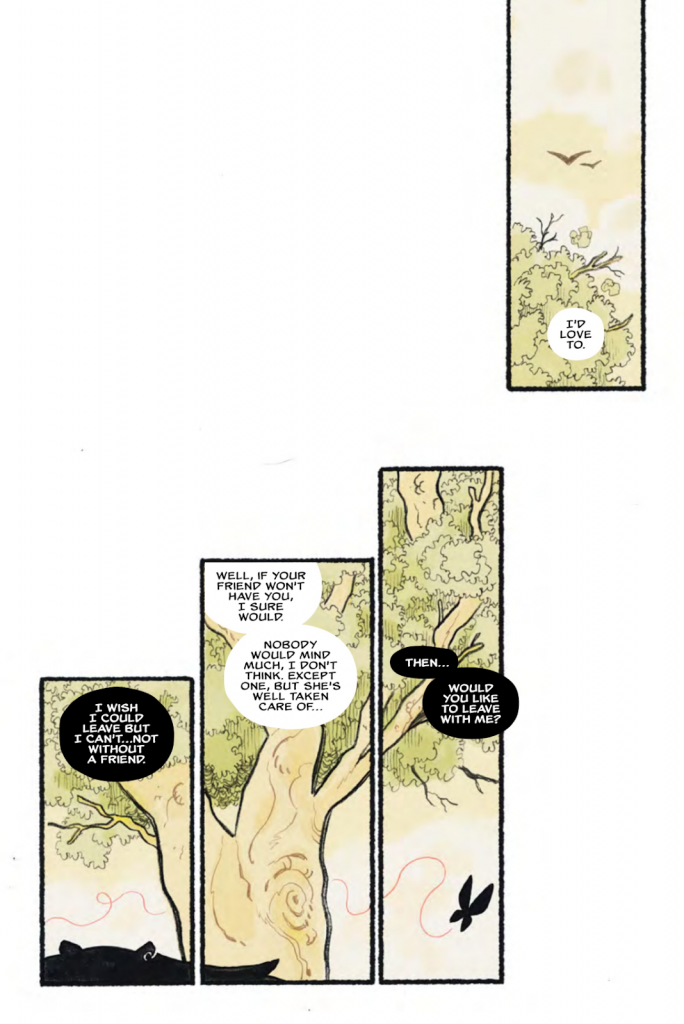

And the breadth of styles Bidikar employs: from the Erlking’s jagged, white text trapped in red-bordered black balloons that ooze onto the page to the serifed, semi-gothic, mixed case narration that sits laid in parchment to the simple, legible, versatile sans-serif dialog. He molds his lettering to the tale, subtly shifting balloon colors to fit with the ambiance or narration to fit the teller: Branch 4’s becomes more looped and cursive, matching the woman telling the story while Branch 14’s look more like a typewriter, set in these perfect boxes with thick outer borders (matching Ba’s for this one tale.)

It would be fair to say Bidikar’s pacing sets the rhythm as much as Ba’s art and writing, acting as the breaths between words and the pauses between sentences, slowing and speeding up the fables to craft or dispel tension at will. Still, this is Ba’s show, and what a show it is.

There are tales to make you weep and tales to make you laugh; tales to make you think and tales to fill you with fear. Ba tells them all and tells them with aplomb, bolstered by expressive, cartoony character designs that both simplify and detail well in equal measure. His semi-angular approach to linework, eschewing perfect circles and ovals for hexagons, rectangles, and triangles with rounded points, softens the harsh visual language without sacrificing the style.

His colors, too, are vibrant and saturated like a storybook. Soft pastels and delicate, colored linework offset the darker inks for spring and summer scenes, as do the clear, blue-whites of winter. Memories are tinged with the haze of time. The underworld is rendered harsh, stark, and saturated. One glance at a page tells you what kind of story you are in and where you might be going.

Ba is spinning a generations-spanning yarn, hopping back and forth across time, never doling out more information than is pertinent to the tale at hand, but, in choosing which tales to tell, paints an ever more layered portrait of its subjects. It’s set, to take the parlance of my own traditions, “long ago in the old country,” crafting a distance from us that allows for the dialogue to be curated, more heightened and storylike.

Ba mines many kinds of folktales to tell his story, earnestly relying on their tropes and archetypes: cruel stepmothers, talking animals (including one trickster fox), knights and outcasts, doomed romances and broken friendships, and monkey’s paw deals with shadowy figures in the woods, to name a few.

And, of course, there are lessons and lessons galore.

It is a poor fable that does not have something to glean from it and Ba knows this. Yes, entertainment is a noble goal in and of itself, but the tradition Ba has chosen to craft within demands, not necessarily a moral, but an observation of the world that one is left thinking about at the end. Actions are more indicative of character than words or associations; the rules of the powerful are weighted in their favor; beware the Red-Eyed Man. I think, however, ‘Branch 12: In Which Tragedy Strikes and War is Declared’ (a very Dickensian title) illustrates this best.

The chapter is ostensibly about the resumption of the fight between Goupil the Fox (yes, fox the fox) and the Erlking, precipitated by the death of a dear friend: the war, and the tragedy. At the end of the chapter, Vivianne the Witch – the main character of Branch 1 and one of the threads we follow throughout the book – chastises them both (separately, of course) for their inability to accept responsibility. The fox acts selfishly, and then blames others for misfortunes he set in motion or directly set-up, while the Erlking hides beneath bluster and trickery, running from some as-yet-unrevealed past, using his considerable power to set others up with what they think they want, only for it to come crashing down around them.

Yet Branch 12 is also set against the backdrop of WWII.

On the two-page spread in the middle of the chapter, one of the few in the book in fact, Goupil walks out of the forest and across a battlefield, the narration chasing him across it. Nothing is said about the war, yet Ba tells us everything we need to know through our understanding of Goupil thus far and the narration that accompanies him. “The Erlking ruins everything for everyone” reads the final caption, small and in the corner below its thinker, a silhouetted Goupil, while the corpse of a soldier looms large on the left, a brown wasteland of destruction, born of hate and vengeance, between them.

The moment lingers as it transitions into Goupil grabbing a dagger from a tree – the Erlking’s dagger – its narration is calm and measured, sing-songy and poetic, yet accessible and not overwrought (except when it needs to be.) The narrator is as much a character as the tale’s subjects, yet is not, save for the “modern” chapters, one of them. He is Ba, outside the narrative, telling us all about it, concealing and revealing with a deft hand.

You can almost hear the crowd in between each chapter, clamoring for the next tale, for more information on Goupil, Beren, or Vivianne. Who is that mysterious girl that Goupil seems so afraid of? Is it true that he killed a giant? What did Roderick say to the Erlking?! What’s next for Vivianne?

It is an oral story, now nailed down into ink and paper, passing on these tales from one generation to the next. Read on. Read on.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply