The single best book I’ve ever read on the subject of comics is Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden’s How to Read Nancy: The Elements of Comics in Three Easy Panels. The subject of that book was a Nancy strip. Not the Nancy strip but a Nancy strip – three panels telling a single joke. By breaking down every single part involved in the creation of the strip, from the character design to the background to the historical and financial context in which it came to be, the writers are able to explore something much greater. By the time they finish, these three panels appear to hold the entire world of comics. If I’m allowed a variation on something Roger Ebert once wrote, although in a very different context, “the more specific something is, the more universal it becomes.”

The best books about comics, be they historical or critical, have some specific point of view to them – the more focused they become on a single subject the better they are at illuminating it. Qiana Whitted’s EC Comics: Race, Shock, and Social Protest succeeds because it talks about a specific artistic movement in a specific moment in time; likewise Black Superheros, Milestone Comics, and Their Fans by Jeffery A. Brown or (on historical rather than critical level) Riesman’s True Believer: The Rise and Fall of Stan Lee.

Jeremy Dauber’s new book, American Comics: A History, goes the other way; it casts its net as far and wide as possible. In case the title doesn’t make it clear enough, Dauber is here to show you the history of American comics, all of it, in direct chronological order – from ye olde newspaper strips through the era of comic books, the rise of the graphic novel and the webcomics revolution, covering over 100 years of art and industry. The book fails. In many ways it was bound to fail, the task is too big. Dauber is Captain Ahab and Moby Dick is gonna drag that ship to a watery grave.

Which is not to say the book is a bad read. For one thing, it is thoroughly researched. If Dauber makes any mistakes in chronology and citation (as opposed to interpretation, which is a matter of personal taste), I did not catch them. For another thing, that level of research means that even someone who has already read his share of historical research in the field would probably encounter something worthwhile. An early anecdote about cartoonist George McManus (Bringing Up Father) calling up the syndicate whenever a plane crashed to claim his artwork was sent on that particular plane to buy up more time is both hilarious and revealing on the workhorse conditions that ruled the industry from its earliest days.

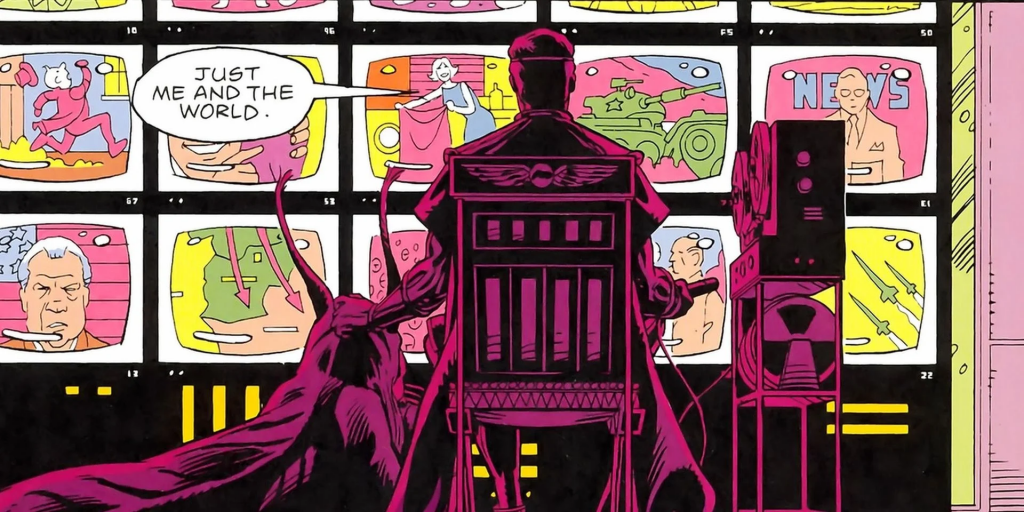

But the closer Dauber gets to the present in this book, the more uncomfortable the reading experience becomes. The bigger the industry becomes, the more companies, creators, and modes of expression it developed, the harder it becomes for Dauber to keep up with the pace. In its latter chapters, the book becomes a hurricane of factoids: series and creators mentioned briefly before being passed on for the next thing. Looking through the index is enough to see that most concepts are referenced once, maybe twice. When a work or creator gets more citations you can expect it to be the usual suspects (Watchmen, Maus).

In an attempt to cover everything, much of Dauber’s writing ends up being almost entirely surface-based: a single passage leaps heroically from American Vampire to Bitch Planet to Sixth Gun to Bookhunter to Kill Them All. Whatever point Dunbar is trying to make about these series, about the conditions that allowed them to co-exist, gets lost in the shuffle. There’s a lot of list-making but not enough analysis. Ideas are brought up but the connection between them is hardly established before moving on to the next idea.

In fact, the closer we are to the present, and to creators who are working right now, the more Dauber leaves behind the critical lenses. Early chapters, for example, had no trouble pointing at the racist aspects of comics strips and comic books alike. Dauber even makes the excellent point that the many Jewish creators of the time had no problem adopting the racist attitude of WASP-ish America when it came to depicting other minorities, partly as a desire to fit in with the majority. However, when it comes to the more recent Habibi, for example, the book refers simply to “a debate that raged around Habibi.” From the last 100 pages or so one would think all modern comics are rather wonderful.

Chapter 7 (“New Worlds”) is a good example of the problem with the book’s approach: starting from an entirely worthwhile notion of exploring the influence of foreign markets on American comics. But, after briefly summing up the career of some of the already famous non-American creators (Tezuka, Moebius, for instance), American Comics: A History veers on to talking about some minor plot influences (The X-Men visit Japan) before veering further to discuss the emerging Direct Market. So stuck is the book within its own chronological framework, so wedded to its chosen path, that it doesn’t have the space to ponder the connection it offers.

What’s the difference between the American market and the Franco-Belgian one? How is the way USA serial comics are collected compared to the Japanese ones? In another chapter, Dauber mentions that Japanese comics began outselling their American counterparts in bookstores (a newer, and far larger, market). This could have been a good opportunity for him to talk about the problems of the collection model in American comic publications or the cost-saving effect of the black and white digest-sized book. Or it could have been a chance to explore how the market and industry very much shape the artwork – both enabling and limiting options. Instead, this becomes just another factoid.

Every single chapter, and sometimes just bits of them, could be a book by itself, should be a book by itself; the subject only appears small because it hasn’t been given the proper look, the proper context. Shine a light on it, the way that Paul Karasik and Mark Newgarden did on a three-panel Nancy strip, and you can see how deep it is. But when you try and shine a single flashlight on a whole mountain, don’t be surprised if you only see small chunks of the surface.

Mark Cousins’ The Story of Film: An Odyssey is another ambitious project that seeks to cover the entire medium of film, not even limited to a single country, in what appears to be a woefully limited timeframe (in his case – a fifteen-hour movie). Cousins succeeds, however, because he renounces the chronological view, choosing to work in a more emotional style that accentuates the way one film relates to another. A lot goes unmentioned, but when the project is done, there is satisfaction to be had. By the end of The Story of Film, we might not know everything there is to know about cinema, but we do know an interesting story. Dauber doesn’t tell us a story, and his own presence as a commentator (instead of a researcher) is often absent from the book. And when the writer disappears themselves, one cannot be surprised that there’s little to connect to.

For students of comics, American Comics: A History is a worthwhile object. For those who want to understand the feel and appeal of the medium, or even look for a particularly good read, it is probably better to look elsewhere.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply