Publisher’s note: Today we have a real treat for you. In 2021, Nhatt Nichols published her first book of comics poetry with Bored Wolves, THIS PARTY OF SOFT THINGS. Bored Wolves is a Poland-based publishing house that focuses on comics poetry. In this interview, Nichols discusses comics poems, translating poetry, and more with Tomás Cisternas, a celebrated Chilean comics poet, and Stefan Lorenzutti, the publisher of Bored Wolves. Bored Wolves will publish a collection from Cisternas in late 2022. Enjoy!

NN: Tell me what brought you both to comic poems. Tomás, I know you come from painting and comics, and Stefan, from poetry. But you’ve both been creating comic poems for a long time, Tomas as a creator and Stefan as an editor, right?

Tomás Cisternas: Hi. In 2008 I started making comic strips because they work very well here in Chile, and people love them. It is an easy way to bring comics to the people, and the truth is that, over the years, I started to be known and my work was very well-liked; a work that only focused on humor and love between couples.

This, for me, became complicated since the style of comics I was buying and reading was very different from the comics I was drawing and sharing. Since I started reading comics, I have always had a greater affinity for European graphic novels.

I always liked Argentine comics Liniers, Decur, and Kioskerman; the latter impacted the way I wanted to make comics since the poetic charge in his texts, mixed with the simplicity and delicacy of his drawings, really made me dream every time I read his work.

I wanted to share my own ideas, my own stories that had this emotional and poetic charge. And I started to do it, but people didn’t like it very much. They only wanted humor and love between couples. I was like that for some years, drawing what I liked and also what people liked. At the same time, I continued reading other authors like Joann Sfar, Jason, Gipi, and I started reading authors of the American alternative comic: Nick Drnaso, Daniel Clowes, Jeffrey Brown, and James Kochalka. Eventually, I had to make a decision: “I keep drawing what people want to read and see, or I start drawing like a complete stranger and fuck it all. I do what I like, whether it turns out or not.” I did the latter.

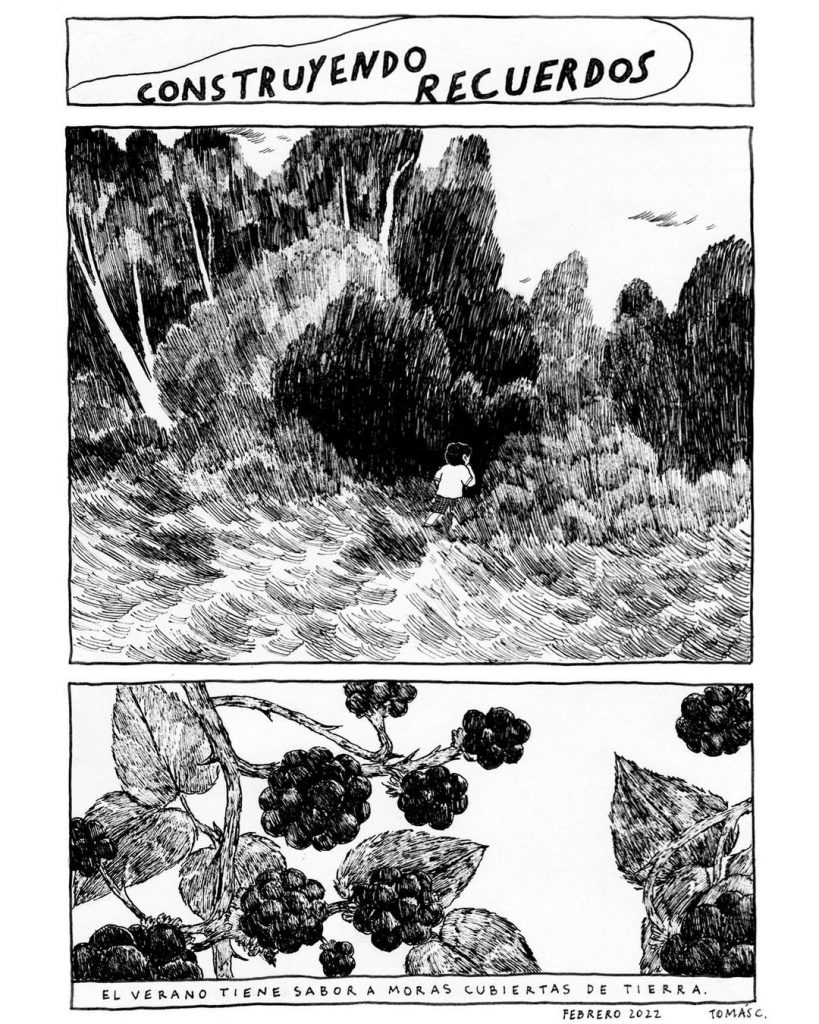

A year went by, and I published a book called Gafas (Glasses), which is nine stories that talk about death in different ways. I had already completely left the other type of comics, humorous ones about couples. I started drawing for love. And then I discovered John Porcellino, and, thanks to him, I do the comic I do today. I learned that poetry is part of all experiences, small and large. As I read a few days ago in a book by Lukas Ruiz, “You can’t live and talk without poetry.” Life, death, and walking are a part of life in my stories that many people identified with; stories that are mine but that I understand are also theirs.

It was a long and beautiful road. And it is beautiful that what I do expresses much more than what I once imagined.

Stefan Lorenzutti: I trace my excitement and interest in the potential for a comic to convey poetry to my favorite children’s picture books. Stories with lyrical cadences like Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, the whittled prose poetry of Jane Yolen in Letting Swift River Go, the gently perfected sentences of Cynthia Rylant in the Henry and Mudge books, and her homey lilts in The Relatives Came. They all planted in me a deep love for, and belief in, the poetic potential of crafted language plotted to sequential drawings. The jump to looking for that in the comics I read and published was natural.

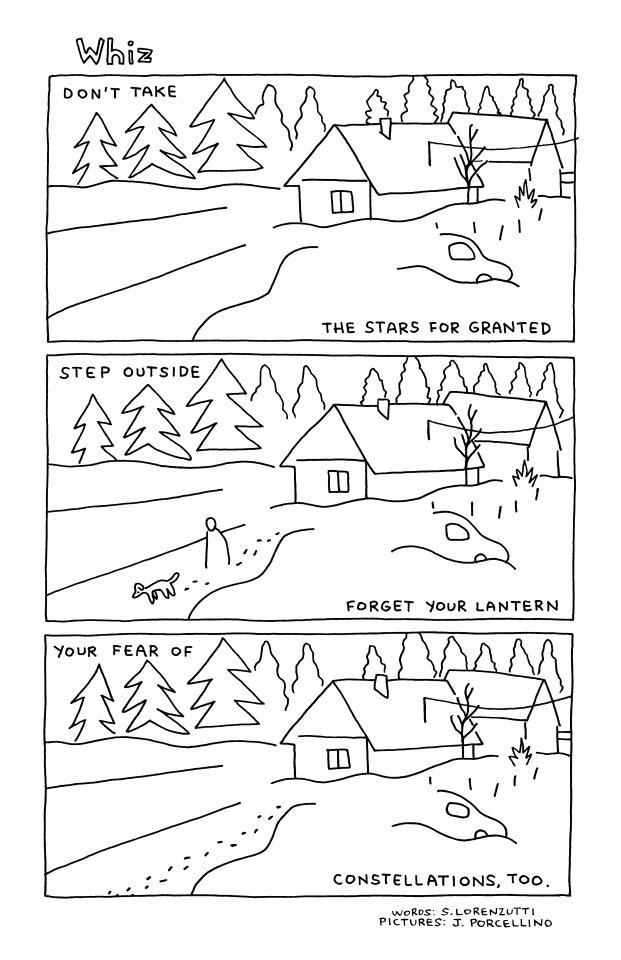

The real epiphany specific to comics came while reading the Basho of South Beloit, John Porcellino. I think one of the best ways to explain to someone what a poetic comic can be is to hand them John’s From Lone Mountain collection, which includes “Freeman Kame,” a twelve-page comic from 2005 chronicling a winter ramble. There are maybe two dozen words across those dozen pages. Mostly, John draws the poetry in puffs of breath and ears swiveling to pick up frosty nature sounds. The other epiphany has been Ellen O’Grady, who endows everyday patterns with lullaby lyricism—walking the dog, cooking dinner while listening to the radio, then lighting candles against darkness pressing against the windowpanes—with the soft grace of ritual. It makes so much sense to me that I discovered Tomás’s work through John and Ellen.

When I get stuck writing a poem, I often sketch it out in panels, which usually eases a phrasing into mind, just by not thinking and, instead, letting my eyes follow my doodling hand staging the scene. That has dislodged poems that were jammed for months. My poems are pretty short. I usually end up with about three to six nutshell sketches out of this. A poem naturally wants to become a comic.

NN: What makes a comic poem successful? After finishing This Party of Soft Things, I discovered that neither writing nor drawing worked so well on their own. Do you think there has to be a codependency between writing and art?

TC: For many, I think, they’re things that can work perfectly well on their own. But when you discover and savor a drawing and text together, they can generate a new and mysterious sensation, very different from what traditional books give you. it’s very difficult, even to read a novel and not imagine it in drawings, something you used to imagine as “movies.”

SL: Coming to this as a literary editor, I feel that for a comic poem to work, the writing has to be fluent and stable enough to stand alone without the art. It cannot use drawings as a crutch. I might be revealing a slight bias here, but I see the art and the comic’s architecture as being in place to shepherd poetic language to the end. But the language needs to be self-sufficient, to begin with. Mind you, some of my favorite comic poems are a single poetic sentence embedded in a detailed, full-page drawing. But especially then, there’s a whole bunch of pressure on that sentence to hold its own.

As a poet, reader of poetry, and publisher of poetry, I need a certain amount of grounding in a poem, some gravity of time and place. Intangible, deliberately opaque poems frustrate me. I’m absolutely okay with expressions of ambiguity, but at least give me a dented tea kettle somewhere in the poem to weigh down the metaphysics.

When I think of the poets I appreciate most, the ones I pull off the shelf daily to ballast myself, it’s pretty easy to start imagining a given poem unfolding in comic panels, whether it’s Jane Kenyon moving between the rooms of a house with a cup of coffee in hand or Meng Hao-jan gathering firewood at dusk while chatting out loud to bats.

When I think of the sort of highfalutin poems that bug me, I see nothing, because maybe there isn’t anything there. The correlation between concise, honest, revealing poetry and concise, honest, revealing comics is clear. The poem can be unpacked, its enjambments paced across panels. In the meantime, the poet has given the artist some trustworthy, tactile nouns to ink.

Poems and comics, especially introspected autobiographical comics, share a lot in common. There’s overlap in the poet and comic artist’s intention. That attempt to simultaneously isolate and frame a memory, an otherwise ephemeral moment, while also allowing it to self-animate, deftly palming a wrinkle in time without chloroforming it.

NN: Tomás, you write in Spanish, and Stefan translates it into English. How does the translation process work? How do you find a connection while Tomás is in Chile and Stefan lives in Poland? Stefan, what drew you to Tomás’ work in the first place? How did you set out to translate it?

TC: Yes, I do everything in Spanish; I still don’t write English, nor do I speak the best way. But Stefan has been there. Before starting the Puddles project, Stefan expressed how he felt when he read my work and offered his help to translate the texts into English for free. He said: “I do it out of love and appreciation for your work.” From that day on, we started a very fluid communication when talking about comics and when talking about life. Stefan is like a good coach; it’s encouraging to work with him.

SL: The moment I saw Tomás’s work—with his comic self wandering along the drizzly Chilean coast on his birthday and feeling happy about that—I knew I wanted to share it in an English translation in whatever way I could. I wrote to Tomás immediately, offering to translate from the Spanish in collaboration with my sister, Michelle Alperin (we are half Argentinean); he wrote back immediately saying yes; within the hour I had fresh pages in my inbox, and we were off on this inspiring, symbiotic collaboration that has now evolved into our forthcoming Puddles collection. Bored Wolves publishing Tomás came quickly on the heels of us beginning to translate him. That heady initial back-and-forth made it clear to me not only that I wanted to share Tomás’s work in English, but that I wanted to collaborate with Tomás in general, and ideally on a daily basis. Which is where we’re at. It’s stimulating, fun, and organic. I feel truly blessed to be in a position to introduce Tomás Cisternas to a wider English-language readership beginning with Puddles. And while we’re not specifically a comics publisher, our core vision is built around pursuing poetry across formats and mediums; classical classifications be darned.

The first strip Michelle and I translated is one called “Magical Beings,” a buzzing summertime anecdote in which Tomás reflects on the invisible existence of cicadas. In three apparently straightforward panels, he does a lot linguistically, as a storyteller and weaver of tenses, shifting from childhood to the present day, place-and-time observation to philosophical conclusion: “The heat of these days is also invisible, but that doesn’t stop me from believing in summer.”

Tomás’s use of language is inherently poetic. He touches pen to paper, and poetic things happen. And they happen in puzzles for Michelle and me to unpack and carefully reassemble. We find that Tomás writes slant, he has a knack for coming at what he sees at a different angle than most people would see it, and this goes into his clausal construction. We spend a lot of time on sentences, running half a dozen variations back and forth, talking through them daily on the phone, with me here in the Polish Highlands and Michelle in Brooklyn. I’m also in constant contact with Tomás, winging questions his way about the exact shade of an adjective or the temperature and relative humidity in an outdoor scene.

Michelle and I are also focused throughout the translation process on the visual comic. We don’t translate in a vacuum. The comic is always open, either on the screen, or I’ll print it out and tape it to the wall. We spend the most time looking at Tomás’s versions of himself on paper. The final test is always matching the English sentences to the sensitive, cerebral soul wandering through Tomás’s panels. Michelle reads out loud, I look at the comic closely, and we get a sense of whether or not both visual and textual/aural elements dovetail yet.

Like John Porcellino, Tomás is very much in the rivers-and-mountains tradition of Chinese poetry, roaming earthbound landscapes while directing introspected thought out into space and, at every moment, tenderly attuned to nature’s stirrings. As with John, Tomás spends a lot of time passing through the wildland-urban interface, covering both where humans pave over fields but also where weeds and vines inevitably crack the concrete and take back the land. The journey doesn’t have to be epic, doesn’t have to be rafting a winding gorge by starlight, for the poet-artist to absorb impressions and insights from their surroundings. It can be up a mound behind your house or along a cracked sidewalk nobody uses anymore. And there doesn’t need to be a grail at the end—unless it comes in the form of finding a pretty pebble that unlocks a childhood memory.

NN: I feel that I’ve seen more poetry books come out in comics in the last few years than in the previous decade. I sense that the combination of words and images of this type is having a real moment. How do you see your work fitting into this? What do you find exciting in the world of comic poetry?

TC: This is an appreciation I make from my home country, where I see what’s happening in the northern hemisphere, from what I’ve seen and read, what comic publishers are putting out.

I see that the autobiographical comic is moving to enormous levels, and the autobiographical tends to have that poetic charge, at least in the images if not in words. Sharing such intimate moments, in a sincere and unpretentious way, fills them with a warmth that can only be found in poetry.

I feel that my work is a mixture of both, there are times when I walk through my neighborhood or among trees, and I feel like writing about the mountain and the rain; other times, when I walk through the same place, I feel like writing about that place and telling what I have felt and lived there.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply