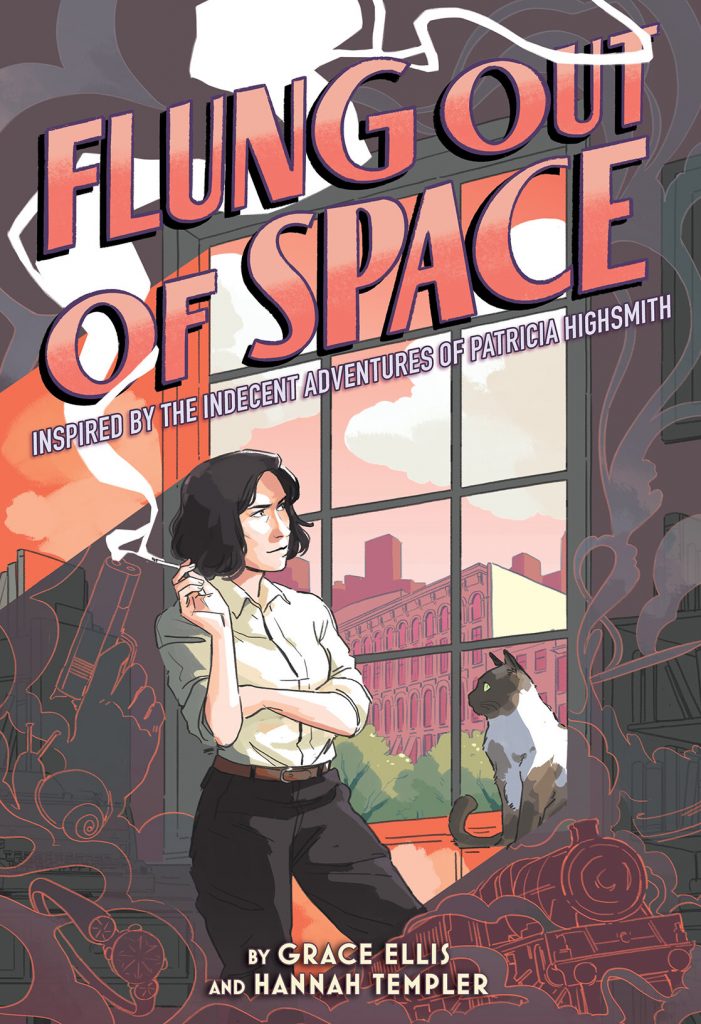

Most people only know Patricia Highsmith as the writer of psychological thrillers, especially those involving Tom Ripley. If, like me, you know little, if anything of her life, Grace Ellis and Hannah Templer’s new graphic work will be enlightening. However, they begin the book with a caveat: their work is a fictional version of Highsmith’s life. The subtitle of the book is even Inspired by the Indecent Adventures of Patricia Highsmith. Thus, for the uninitiated, it’s easy to be confused as to what is factual and what isn’t. Ellis writes in an author’s note in the beginning that they don’t shy away from the difficult parts of Highsmith. She was anti-Semitic, racist, and misogynistic, and they show that part of her life, so that part isn’t fictional; they take it head-on. It ultimately doesn’t matter what’s technically true or not, as Ellis and Templer tell the story of a writer at war with herself, unhappy with the work she was doing as a writer and unhappy with her love of women, trying her best to discover who she was in both areas.

The story centers on Highsmith’s early career when she was a comic book writer, cranking out scripts for two stories a day. Whenever she sits down to write, though, her thoughts end up turning to what will ultimately become the thrillers she’s known for. In this book, that will lead to her first novel Strangers on a Train. She needs the comics job to pay the bills, but it’s clear her focus is elsewhere. She ultimately begins freelancing with Timely Comics after meeting one Stanley Lieber—who prefers to go by Stan Lee, of course—in order to make more money. Even when her boss discovers she is essentially two-timing the company, he keeps her on because she’s so good.

In her personal life, she tries to date men, but that doesn’t go well. She goes to parties with men, but she often goes home with women, which she then quickly regrets because of the norms of her time. In an effort to find what she believes is a cure, she’s seeing a therapist to help her get over her lesbianism. Her therapist even suggests comics might be part of her problem. Highsmith eventually meets Virginia, who sees her as somebody she doesn’t want to be. Even Highsmith admits she wants to be who she is without feeling guilty. However, Virginia is married with a daughter, and the husband threatens to take their daughter away if Virginia leaves him, so Highsmith is left alone.

She ultimately combines her authorial and personal life by writing The Price of Salt, one of the first novels about LGBTQ+ characters to have a happy ending. However, Highsmith publishes the work under a pseudonym, Claire Morgan, protecting her reputation. It wasn’t until 1990, thirty-eight years later, that Highsmith republished the novel as Carol under her own name (that novel was adapted into a movie in 2015). The rest of her novels are traditional thrillers, leaving The Price of Salt as an outlier in her publication history. Ellis and Templer’s book ends with Highsmith alone in a bar just after a woman who doesn’t believe Highsmith wrote the book that changed her life has walked out, showing that the disconnect between her personal and private life continues. This story doesn’t have a happy ending, at least not a conventional one.

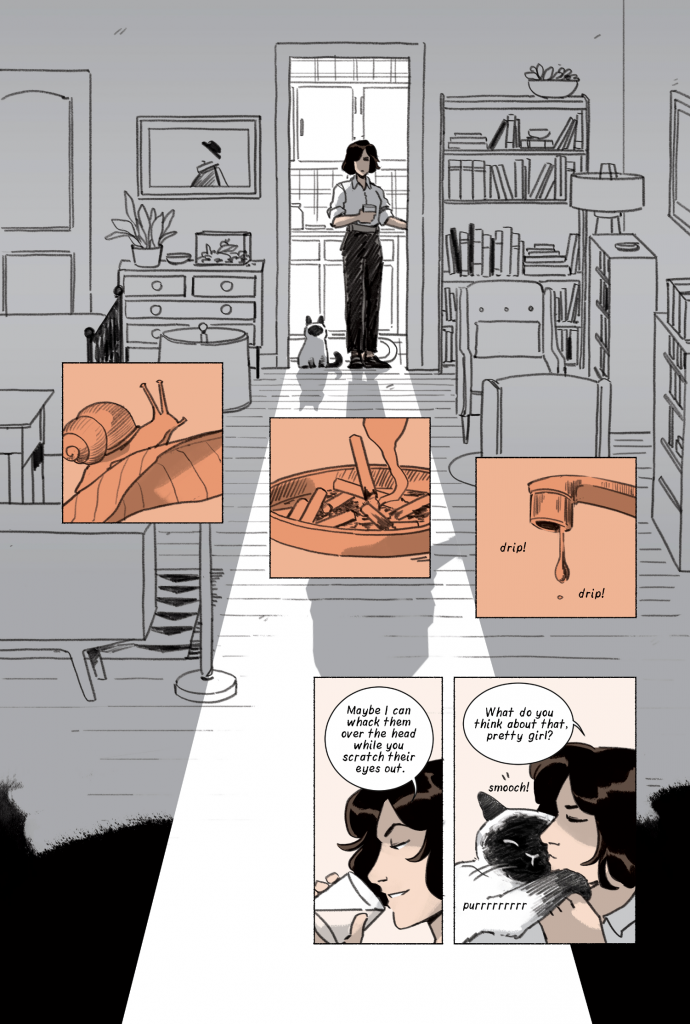

Throughout the work, Templer mixes a variety of close-ups and distant shots to help reinforce ideas and emotions. Her work with full-page spreads is especially strong, especially when the art is the only means of moving the plot along. For example, in the scene where Highsmith is dancing with a man (Marc), but looking at the piano player she will ultimately go home with, Templer lays out a double-page spread, with Highsmith and Marc on one page and the piano player on the other. She uses a number of insets that show close-ups of parts of Highsmith’s face and the piano player’s fingers to convey Highsmith’s shifting attention. Similarly, when a co-worker refers to Highsmith as a “dyke,” Templer sets Highsmith apart on a separate double-page spread with the word taking up most of that spread, and in all caps. Templer’s art reinforces the isolation Highsmith feels here in the same way she conveyed Highsmith’s shifting attentions earlier. Ellis and Templer work well together to mix dialogue and images to convey the conflicted emotions Highsmith feels throughout the book.

They also draw on comics history to explore the ways in which people viewed comics as a negative influence on people’s lives. In this case, comics are presented as both beneath Highsmith’s interest and a cause of her lesbianism. Her therapist, in fact, says that the most rudimentary advice she can give Highsmith is to stop writing comics, as they’re leading her “down the path of degradation” and confusing her morals (64). Flung Out of Space takes place around 1950, the year Highsmith published Strangers on a Train, and it’s telling that the Comics Code Authority was formed in 1954. Mainstream society was already convinced comics could harm people, especially children. For Highsmith, writing comics is just a way to pay the bills, but she views them as nothing more than “stupid stories for stupid children and even stupider adults” (69). The fact that Ellis and Templer are telling her story in graphic format, then, becomes ironic, but perhaps an irony Highsmith might have appreciated, had she lived to see what comics could become.

Ultimately, the book balances the inspiration for The Price of Salt with the reality of the price Highsmith’s life took on her, while acknowledging that she is far from a perfect person. By the end of the work, Highsmith has published Strangers on a Train and dedicated it “to all the Virginias,” but she is alone in her personal life (169). Even when she is able to publish The Price of Salt, she has to sell it as a pulp book under a pseudonym, assuring others won’t see the variety of writing she is capable of. While she may be a terrible person, she does make changes throughout the novel, ultimately treating her co-worker Andy and agent Margot better, even before her literary fortunes change.

Unlike her fictional work, where the two lesbian characters have a happy ending, Highsmith had a successful literary career doing the type of writing she wanted to do, but she was unable to find happiness in her personal life. Ellis and Templer celebrate the work she was able to do, despite those struggles, while also showing her to be the flawed person she was. They see her as a human with talent, which is all any of us can ask for.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply