Whether or not one is willing to admit it, we all have a tendency towards voyeurism. Reading about other people’s weird/ mundane/ humorous/ devastating life experiences grounds us in our own – validates us.

It has also become equally a tendency, if not more of a compulsion, to share yourself with others. Most people have projected their lives and sense-of-self on social media, which, for the vast majority of us, has only intensified over the past few years, as these platforms became our primary social reality during quarantine.

Consider, then, autobio comics; the graphic memoir; diary comics: mainstays of the comics landscape and the entry point – if not career-defining practice – for many cartoonists, including myself. Like the social media-indoctrinated culture we live in today, the emphasis on personal experience in these works functions hand in hand with the fact that these comics are usually publicly shared. Autobio ups the ante, however, as the self is captured not by the camera or language alone, but by lines from one’s own hand. An irreproducible excretion of line from the body, a strand of DNA.

Recently, I’ve had several conversations with cartoonists who work in autobio about sharing their lives in this way over time – some had for decades, some for just a few years. Every cartoonist I spoke with told me that, for at least one published work, this method of life-sharing had caused so much upheaval – or paranoia about upheaval – that they regretted publishing it, and in more than one instance “would take it all back” if they could.

So, what is the nature of our impulse to create these comics? Why do we choose to publish them? Why do we do it when the work sometimes comes back to haunt us or even has a tangible impact on our lives?

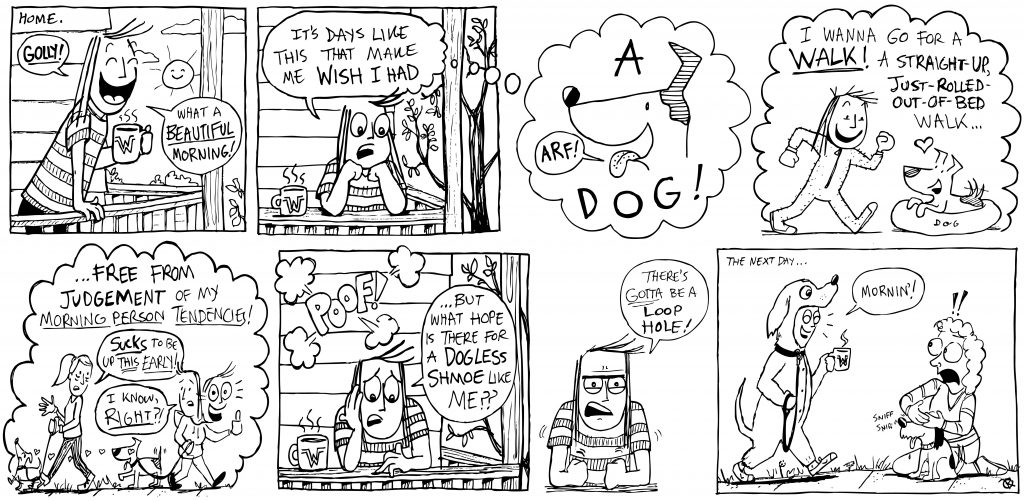

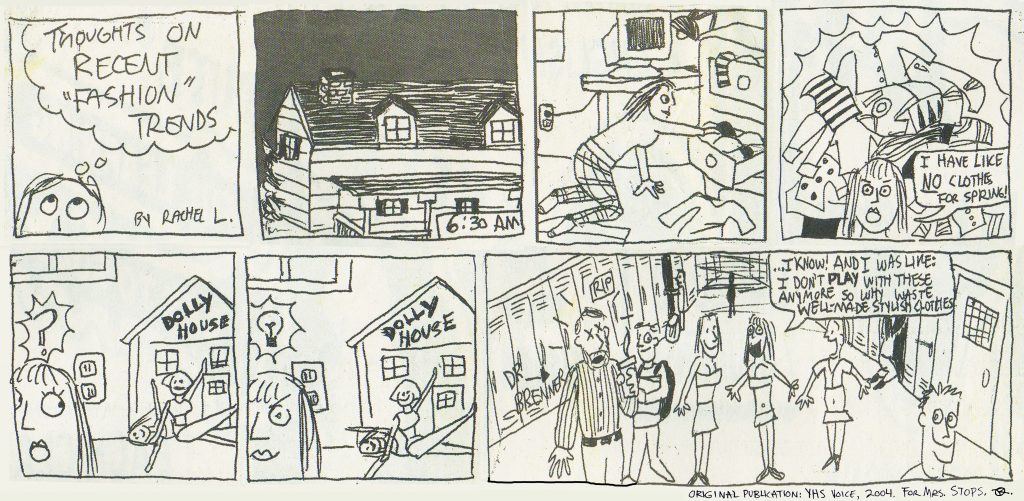

I started publishing autobio comics as a high school freshman in our school paper, The Voice. It was a half-page strip called Thoughts On… It was slice-of-life, it was funny. It was about me and my community, and it got me into college where its evolution became a column in the literary magazine, and then my thesis. It had the same bent and number of panels that I later would have for my newspaper strip, Rachel Lives Here Now, which ran for eight years as a weekly (2013-2021) – four in Vermont’s statewide paper, Seven Days, four as a webcomic.

Thoughts on… and Rachel Lives Here Now both gave me a name in the places where I created them. More than that, they shaped my identity and reputation – or rather, my graphic storytelling did. Comics provided unique control over the way people interacted with me and consumed my life experiences – via the manipulation of lines and manipulation of panels. I could have the body of my choice, the hair, the clothes. While my body ages, my “character” lives on – my chosen body can stay the same forever. A panel is not only an aesthetic decision, it is also a unit of time, and I could control the relative importance of every moment: in the panel size and shape, in the panel position, in the size of the gutter, the lack thereof. Making comics about my life was an act of reclamation, and, for both strips, I found an audience that took away from them the person I wanted to be known as in the world.

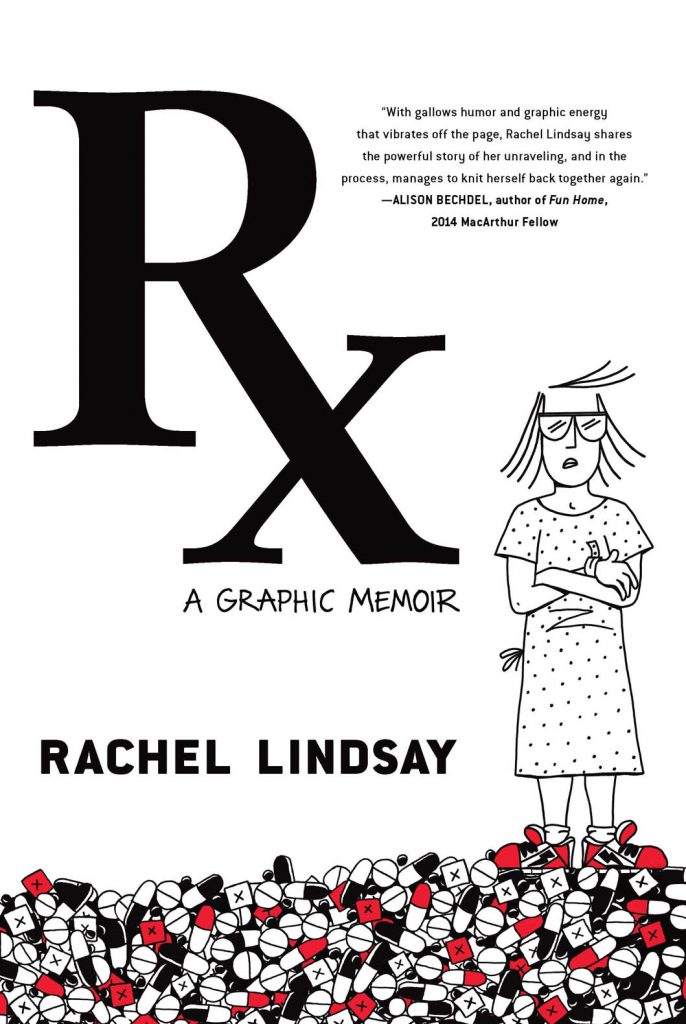

The publication of my book, RX: A Graphic Memoir, has resulted in a different scenario.

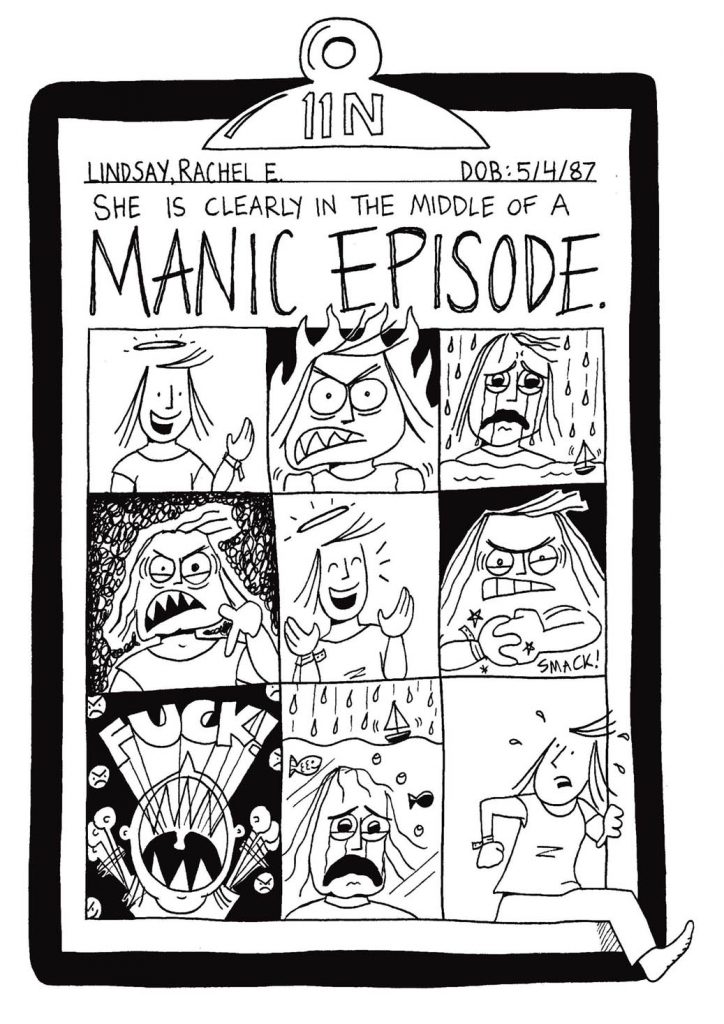

RX is my dark night of the soul, a twisted coming-of-age story, covering a mental health crisis that came on the heels of a mind-fuck work experience in my early 20s: creating psycho-pharmaceutical advertising while also carrying a mental illness diagnosis. My book discloses two things that hardly anyone knew about me: that I have Bipolar I, and that I was once hospitalized against my will. I liked that those things were private. However, the story of that moment presented itself to me in such a way that it had to be written and shared, as a comic. There was never a more important time in my life for me to have control over, and creating a comic was the best way to do that.

But for whatever healing happened in its creation, the hurt happened when it was out in the world. I have realized that I have erased a critical boundary, problematized my identity – on paper and in the physical world. I have a new trauma now: the permanent, instant availability of that work to anyone and everyone – not just the content I made, but everyone’s opinion and dissection of it – of me. As it grows older in the marketplace and cannot be perused in a bookstore, the primary understanding of the book, of my lived experience, will be the synopsis written by someone else.

Essentially, my graphic storytelling won’t even matter.

Despite the amazing opportunities and attention my book received, my flow state bore a public piece of work that places me in a stigmatized identity. There will always be grounds for interpretation of my behavior, attitudes, and even my drawings as a feature of my illness. Everything, even the safe space of the comics translation of myself I’d always created, was now up for pathologizing. From the funny pages to the looney bin.

I sometimes lay awake at night before a date or a job interview terrified at the prospect of that person Googling me and learning about me and that moment in my life – without reading the book. It upset me to think that my diagnosis and my hospitalization might never again come up organically, and that I can’t control other people’s knowledge of or engagement with that information. After my book was published, I asked a member of my (geographic) community – my Rachel Lives Here Now audience – if they believed people thought about me differently now, since the book had been published. They said yes.

Undergraduate/graduate/Ph.D. students often reach out about papers they are writing with questions for me or permission to use images. Pretty cool, really –but sometimes not so much. One disclosed that they had referred to me as having a disability and that they “hoped that was ok.” Yes, technically Bipolar Disorder is a disability, recognized by the Social Security Administration and the Americans with Disabilities Act. But the label is very complicated for me, and to know that someone took the liberty of applying that to my identity was uncomfortable and disorienting.

It means so much to me that my book has provided support to people who need it, and that it has inspired others to make work about their mental health challenges (though I worry that they may experience the same fate). I never intended RX to be a peer support tool or educational in any way, but it resonates with an enormous spectrum of people – from the neurodivergent to the neurotypical – and I am happy that is the case. One college student told me through tears that RX made them feel less alone. Possibly the most moving feedback I have received – because I know that specific version of loneliness so well.

I’m also proud of the work it’s done to provide perspective to healthcare professionals about that specific medical experience, aided by my visibility in the Graphic Medicine community.

It’s an incredible power, to be able to externalize your life exactly how you want it to be portrayed, to recount – or recast – an experience, to build a world. The first alternative comics opened a raw, underground confessional space that has only continued to grow and evolve. Wimmen’s Comix (the 70s-90s), for example, responded to topics like reproductive freedom, domestic abuse, workplace discrimination, sex, and sexuality— all of which faced their own stigmas and taboos in the broader conversations of the time.

The question is what to do now— now that there is illness infused with my identity as a creator, now that my safe space doesn’t feel quite as safe. It comes back to my earlier question about the impulse to create this kind of work. When I really need to understand myself, I have to externalize myself. I have to watch myself walk through the moments that hit me, and I have to show and tell why those moments were significant. Unfortunately, it will take a long time for me to shed the self-consciousness I feel now, the hyper-awareness of all the ways my work could be spun.

I’ll have to continue to make comics because only creating more and sharing more can generate new opinions and reactions. And maybe this time around I should remind myself more often that I don’t have to show all of myself. All anyone can do is keep living, and for autobio cartoonists, that also means keep showing people how their lives are being lived.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply