The term post-apocalyptic has begun to feel disposable. Once a genre marker loaded with existential dread, it is increasingly treated as visual shorthand: ruined skylines, abandoned cities, the familiar language of destruction rendered at ever-greater scale. The question that once sat at its core: what happens after everything ends? has been replaced by spectacle.

Stories about the end of the world have existed for as long as storytelling itself. Long before zombies and nuclear wastelands, religious texts, myths, and folklore wrestled with collapse, judgment, and renewal. The fascination is not new. What has changed is how often the aftermath is imagined as an event rather than a condition, a single moment of devastation followed by survival or rebirth.

But the reality of collapse, as history repeatedly shows us, is rarely cinematic.

The world does not explode.

It fractures.

What follows is not an empty landscape but a damaged one, a place that still functions, unevenly, held together by habits, routines, and people who were never prepared to carry its weight. Systems erode. Trust thins. Communities adapt or withdraw. Collapse arrives not as a single rupture but as a slow loss of structural integrity, one support beam at a time.

This distinction matters because the stories we tell about collapse shape how we understand survival.

Where post-apocalyptic fiction often emphasises absence, the absence of people, institutions, and life, post-collapse stories are defined by presence. The presence of trauma. Of memory. Of fractured communities continuing to exist inside broken systems. It is less about what has vanished and more about what remains, strained but intact.

This kind of collapse is not theoretical to me. I grew up around the remnants of it. When heavy industry declined across Scotland, the world did not end, but it changed permanently. Dockyards closed. Coal mines shut down. Work disappeared, followed slowly by opportunity, confidence, and identity. Communities did not vanish overnight; they fractured unevenly. Some people stayed. Others left. The physical structures remained long after their purpose had gone, and the effects were carried forward quietly, generation to generation. Life continued, but under strain.

These were not apocalyptic events. There were no explosions, no sudden endings. And yet their impact was total for the people who lived through them.

Comics are uniquely suited to telling this kind of story.

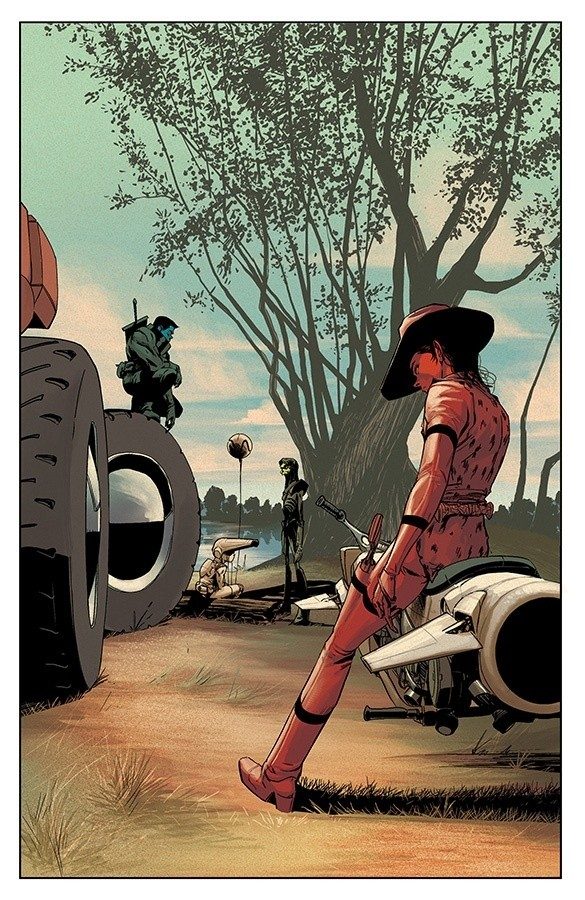

Unlike film, which relies on momentum and spectacle, comics are built from stillness. Panels freeze moments in place. Gutters create an absence without explanation. Time stretches or collapses depending on how the page is structured. A single image can carry weight without movement, allowing the reader to linger inside the damage rather than rush past it.

This makes comics especially effective at depicting collapse not as a moment, but as a condition. Repeated locations can appear across pages, almost unchanged at first glance, until small details reveal erosion, a boarded window, a missing sign, a familiar space slowly emptied. Environments tell stories without dialogue. The reader is invited to notice what has been lost rather than being told it has disappeared.

Some of the most unsettling collapse narratives in comics embrace endurance rather than finality. There are stories where the world has not ended in fire but simply continued without most of us, where survival itself becomes a burden rather than a victory. In these stories, the horror does not come from destruction, but from repetition: endless days, hostile environments, and the psychological toll of carrying on when there is no promise of renewal. The absence of resolution becomes the point.

In a post-collapse narrative, comics’ formal language becomes thematic. A fractured page mirrors a fractured world. Sparse layouts emphasise isolation. Crowded panels communicate pressure rather than action. Silence, rendered visually, becomes as important as dialogue. The reader is not overwhelmed by destruction but invited to sit with its consequences.

This physical relationship between reader and page matters. Comics demand pace. They allow stories to be taken slowly, returned to, and held in the hands. The reader controls the movement through the world, choosing when to linger, when to move on, when to look again. Collapse, in this sense, becomes something felt rather than observed: not a spectacle unfolding on a screen, but a structure the reader moves through panel by panel.

This capacity for re-reading is crucial. Collapse, by its nature, is rarely understood all at once. It is recognised in hindsight, in the moment when a reader realises a background detail mattered, or that a gesture meant more than it first appeared. Comics encourage this delayed understanding. A page can be revisited after context has shifted, allowing meaning to change without the story itself changing at all. The reader becomes complicit in the act of interpretation, assembling significance from fragments rather than being delivered a single, authoritative version of events.

In this way, comics mirror the lived experience of collapse itself. People do not recognise the moment things begin to fall apart until they are already deep inside it. Meaning accumulates unevenly. Understanding arrives late. The story does not announce itself as an ending; it reveals itself gradually, through absence, repetition, and quiet realisation.

This also reshapes how we think about survival. The fantasy of the lone survivor is seductive, but ultimately hollow. A world where people endure entirely alone is not a world recovering; it is a world already finished. Post-collapse stories gain their weight from proximity: people forced together by necessity, negotiating shared trauma, learning to coexist inside broken systems. Community becomes fragile, imperfect, and essential all at once.

Perhaps this is why collapse stories resonate so strongly right now. Not because we are waiting for a single catastrophic event, but because we recognise the feeling of gradual erosion. Division deepens. Trust fractures. Institutions strain under pressure. The fear is not of sudden annihilation, but of watching something familiar change beyond recognition while still being expected to live inside it.

What draws us to these narratives is not the fantasy of survival against impossible odds, but the quieter recognition of ourselves within them, individuals navigating shared trauma, finding community in fragments, holding onto pillars that have not yet fallen.

The end does not mean the end.

It means something has ended.

And something else, inevitably, begins.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply