Charles Schulz once famously defined a cartoonist as “someone who has to draw the same thing day after day without repeating himself”; Stan Lee, for his part, declared that what readers want isn’t change but “the illusion of change.” The specific merits of Schulz versus Lee aside, the two quotes both get at the same ultimate worldview — the inevitability of artistic conservatism, not necessarily in the overt social sense but nonetheless in its approach to form, tone, and narrative. For better or worse, this is an approach to art that fundamentally retains the reader, not the artist, perpetually in mind, as it prizes familiarity: as soon as a work becomes less about a specific narrative circumstance and more about its characters, the usual guarantee is that these characters will not change much, and that they will forever deal with, more or less, variations on the same core issues, the same themes.

With this in mind, we may look to Takano Fumiko’s Miss Ruki, the latest manga offering from New York Review Comics, published this past September with a translation by Alexa Frank. Manga is in itself a somewhat infrequent sight from NYRC; in truth, this is only the fourth such title in the imprint’s catalog, preceded by Ryan Holmberg’s translations of Ninja Sarutobi Sasuke by Sugiura Shigeru, The Man Without Talent by Tsuge Yoshiharu, and the shorts collection Slum Wolf by Tsuge Tadao — all thematically heady works, with Sugiura’s preoccupations of artistic lineage and the Tsuge brothers’ (vastly divergent) explorations of a down-and-out Japan trying to scrape by. Miss Ruki, then, readily sticks out as a crowd-pleaser. Serialized in two-page increments in the comics section of the women’s magazine Hanako, it is a comic designed to be isolated from both intra-comics concerns and broader-world concerns, its narrative and tone non-confrontational.

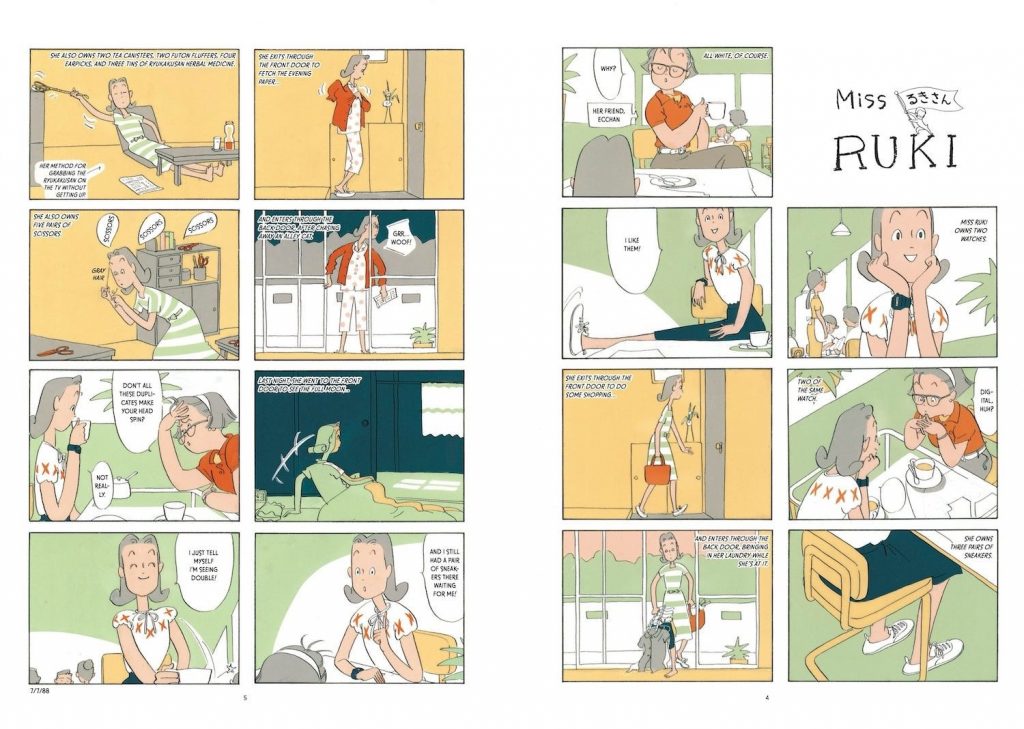

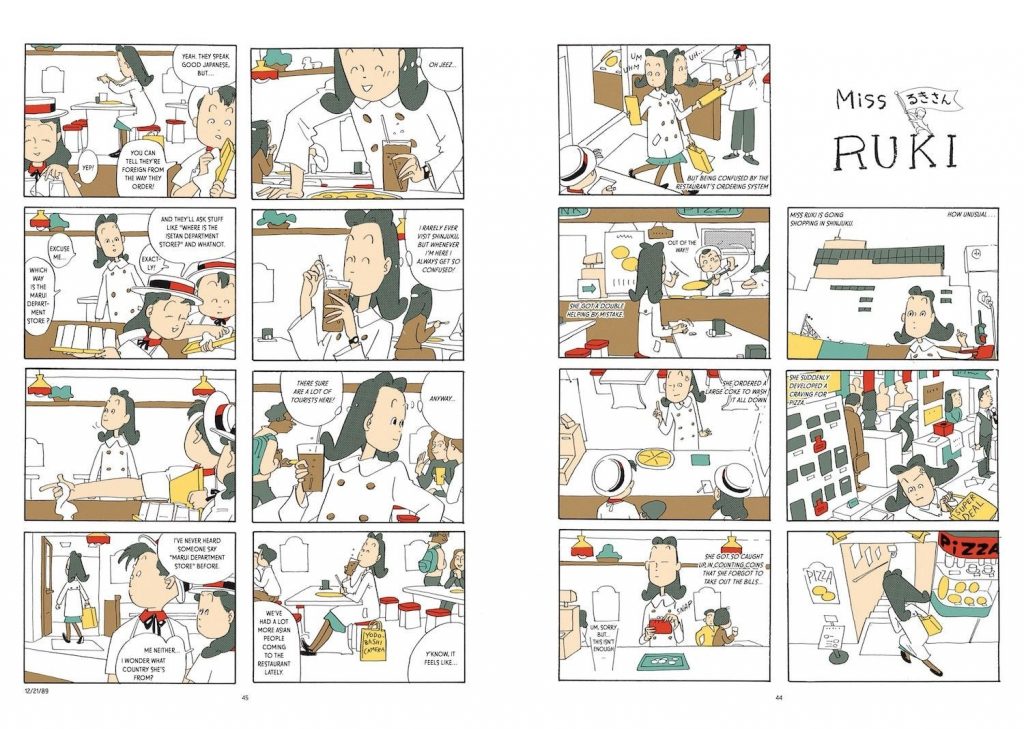

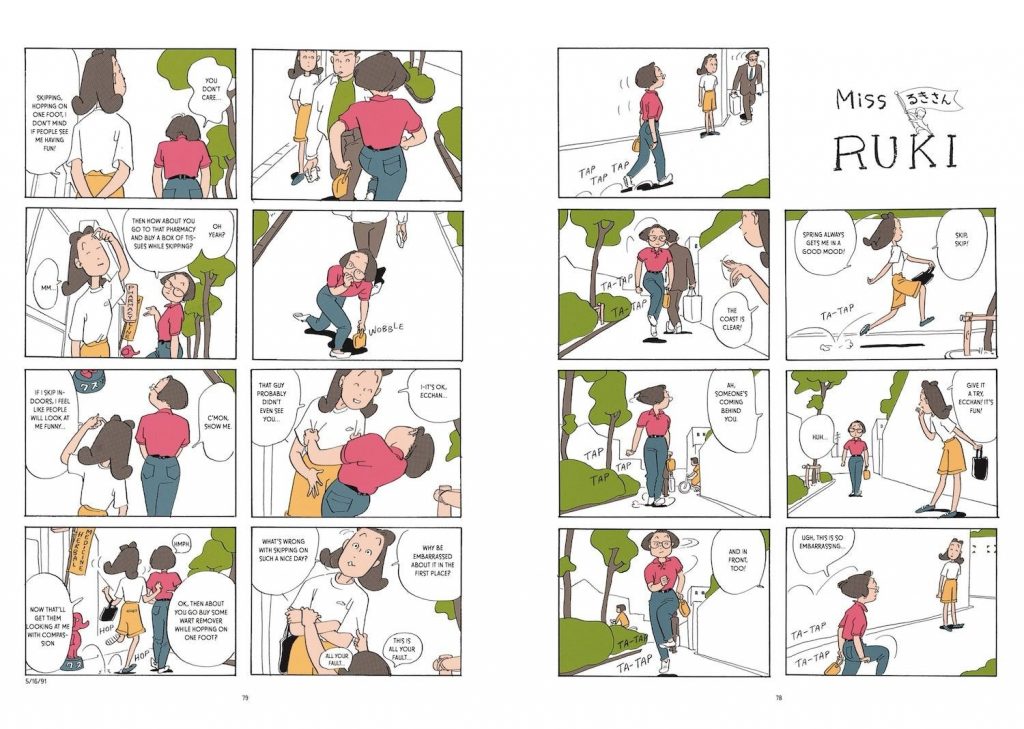

The strip’s layout makes me think, again, of Schulz, with his equally-sized paneling for optimal arrangement within the broader newspaper sheet — each individual strip in Miss Ruki is organized into four columns of equally-sized panels (the first one being an unvarying title panel), and it’s only rarely that two or more panels are merged together into a larger unit. As the top priority seemingly becomes the ease of arrangement within the initial publication venue, the predetermined format dictates the form. It’s a considerable constraint on experimentation (certainly given the flexible malleability of Takano’s self-published short works, as cited in the translator’s notes), but one that Takano takes to with remarkable ease — her cartooning, above all else, is a practice of economy, her lines flat and almost dashed off in how casual they are, sharp and uniformly weighted; with the exception of a handful of installments watercolored by hand, color is applied flatly, less an enrichment of the aesthetic experience than a legibility aid, separating between the various forms and surfaces (one notices that the chosen hues are largely inconsistent — the protagonist’s hair, for instance, may be dark, greenish, or a light brown depending on the individual strip). Takano’s backgrounds, likewise, are sparingly communicative rather than atmospheric, frequently dropped away entirely. Here, in these tentative environments, we may find the whole of Miss Ruki’s worldview: the world as something that can be, in one’s mind, erased, scrapped, disregarded; life as something that may persist not despite its circumstances so much as completely independent of them.

By and large, Miss Ruki is a ‘timeless’ strip, operating on a cyclical-seasonal time while avoiding, for the most part, any substantial narrative shifts. This serves a two-fold purpose: on the plot level, it ensures that a casual, irregular reader will never miss a crucial turn; on the political level, it is an unremarked-upon departure from the anchors of the real world, exempting the strip from needing to respond to events in real time. The strip revolves around Ruki, a twenty-something woman who works as a processor of medical insurance claims, and her best friend Ecchan. In Ruki and Ecchan, Takano finds a perfect odd couple: Ruki works from home, Ecchan is an office worker; Ruki is a fast worker who can thus afford to take it easy, while Ecchan is high-strung and overworked.

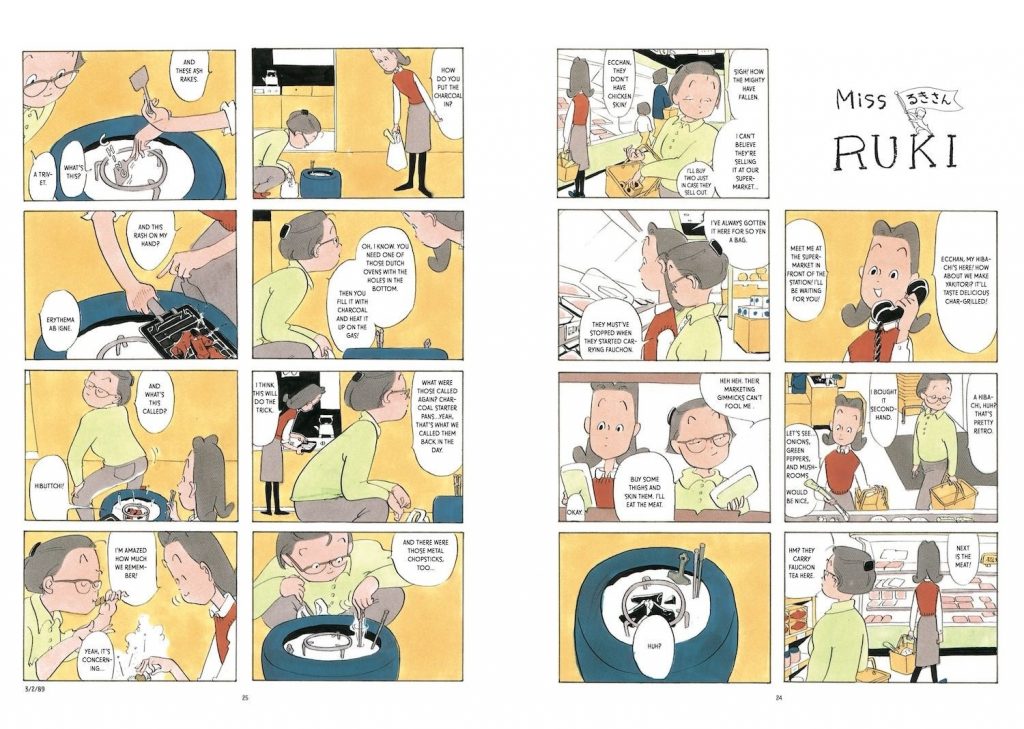

Key to the two characters’ relationship is a certain unfairness on Ecchan’s part. Ruki, we know, practices acute stoicism in all aspects of life. One strip, nearing the middle of the run, charmingly summarizes her worldview: after a succession of pratfalls, trips, and slips on her own part, she sees a different girl falling down the stairs; as the girl cries, about both the pain and the embarrassment, Ruki muses, Anyone who reacts like that has very rarely fallen down in their life. Ecchan, however, is completely in thrall of an appearances-obsessed culture: being an office worker, Ecchan tends to minimize Ruki’s work and diligence (“Oh, you’re working for once?” she asks at the start of one strip, and playfully accuses her of “[living] on taxpayer money,” even though it is Ruki’s extreme diligence and productivity that affords her a laid-back lifestyle); she dismisses Ruki as un-chic, castigating her for such transgressions as laughing on the train or gleefully skipping in public.

This dynamic, compounded with the de facto sliding timeline approach, is an interesting demonstration of what we might call sitcom realism, where a joke gains poignancy through sheer repetition even though the characters lack the memory to sufficiently perceive that repetition. Ruki and Ecchan are, largely, stock characters; facets of their personality are revealed and refined over time, but, at the same time, they are in stasis, never truly allowed to change in intrinsic nature or in circumstance. This poses an interesting constraint on emotional depth, as there will never be any lasting conflict between Ruki and Ecchan; at the same time, however, the repetition does begin to sow in the mind of the reader an inkling of, if not an outright desire for, an explicit clash, a lasting dissonance.

To this, Takano finds a simple solution by taking a nigh-cosmic stance between the two characters. Uniformly it is Ecchan who turns out to be in the wrong, purely through her own dissatisfaction: in one strip, she insists that Ruki wear a needlessly fancy outfit for a social function, but the large bow on Ruki’s blouse only turns out to be an impediment; in another, she initially scoffs at Ruki for the latter’s habit of reading children’s books, only to find herself positively illuminated by a children’s book called “How Politics Works.” Even when there is no friction against Ruki, the limits of Ecchan’s ideology nonetheless come to the fore — when Ruki tells her about her landlord having a mistress, Ecchan’s immediate response is lust and envy: “He’s got land and a girl on the side? Wow, I didn’t realize men like that were still on the market!”

Similarly, it is worth examining Takano’s approach to romance within the strip. Fairly early on, Takano introduces potential love interests for both of her main characters; for Ecchan, there is her office colleague Ogawa, while Ruki’s is an unnamed bike shop employee. Naturally, these love interests are an extension of Ruki and Ecchan’s own dynamic: Ruki’s would-be beau is charmingly earthly, while Ecchan’s is an embodiment of not only her corporate-careerist aspirations but, even more crucially, her desire for conformism — when Ogawa is introduced in a company Christmas party, part of the joke is that every single man in Ecchan’s company looks exactly the same, with the same hair color and suit.

Here, Takano finds herself at another junction: not only would a romantic advance necessitate a narrative advancement — an addition to the small cast of characters would inherently knock the strip out of its existing balance — but it would also venture dangerously close to didacticism, sanctifying romantic love and eventual marriage as The Way to Go. For this reason, the cartoonist decides to, in essence, disregard her own introductions, as from the point of their respective introductions onwards the two men appear only occasionally: Ogawa sends Ecchan a happy new year card one time, and twice more he comes up in conversation (when Ecchan dreams that she was married to him, or when Ruki jokes about going into the office disguised as Ecchan); the bike-shop man usually appears as comic relief, saying the wrong thing to Ecchan and deflating her ego, but when he does flirt with Ruki it goes more or less nowhere. Notably, we do know, from a throwaway remark, that Ecchan is looking for romance, but, because her searches remain perpetually off-page (and perpetually fruitless), they likewise remain within the realm of the predefined conventions.

Where the outside world does manage to filter into the strip, it is usually not at the expense of tonal incongruity. Even when there are attempts at political commentary, they are usually soft enough to avoid the discomfort of an externalized ‘stance’ — when Ecchan complains about the recession, the reader remembers that she is constantly worried about money, and about the outward signifiers of money and class, to start with. In her translator’s notes, Alexa Frank notes the October 29th, 1992 strip, in which Ruki buys steak at the supermarket on a whim and winds up without enough cash to buy rice, as one demonstration of the recession, but I find this installment interesting specifically because Ruki is not poor — even here, the narration notes that Ruki “deposited all the cash she had lying around at home in her postal savings account,” thus shifting the focus away from an encroachment of material conditions and toward a deeper, more existential limitation of Ruki’s generally-diligent lifestyle, the long-term suddenly disrupting the short-term. This is, of course, shocking in itself — up to this point, Ruki’s clumsiness has been limited to slapstick physicality, yet, suddenly, we see the cartoonist indulging in straight pathos as her protagonist, in the rain, almost begs the throng around her to buy the steak from her so she can buy her rice. But this shock, too, is swiftly resolved — finally, she stumbles upon a presumably-cheap-enough street-food stall.

In the two strips that follow, Ruki and Ecchan decide to both stop working to see which of the two can keep up unemployment for longer, and Ruki simply decides to sell her belongings and leave for Italy; in a postcard, she speaks of the blissful decadence of “the Neapolitan way of life,” though in an enclosed photograph her life seems hardly changed at all, as she still sits on the floor, at her table, eating fish and rice (with chopsticks). Only the view outside the window has changed. It’s a charming ending: when the localized circumstances have changed, Ruki simply finds a new location to retain the old ways; change exists in the interest of sameness.

Is such change sustainable? Hard to say; it is on this note that Takano elects to conclude her strip, and although the sole revisit — a one-pager drawn ten years after the end of the original run — indicates that Ruki is back in Japan, it does so in a way that pointedly avoids any semblance of continuity. I cannot help but think here of Vincenzo Latronico’s novel Perfection, in which a couple of freelancers chase both the ‘good life’ and the outward appearance of being good people, but Latronico, with his shades of John Darnielle and David Foster Wallace, renders the chase as naturally futile, a surefire recipe for dissatisfaction.

In this case, however, I strongly feel that to assume failure would be distinctly un-Ruki-like. For better or worse, with Miss Ruki, Takano Fumiko fights to create a crowd-pleaser; for better or worse, she thoroughly succeeds.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply