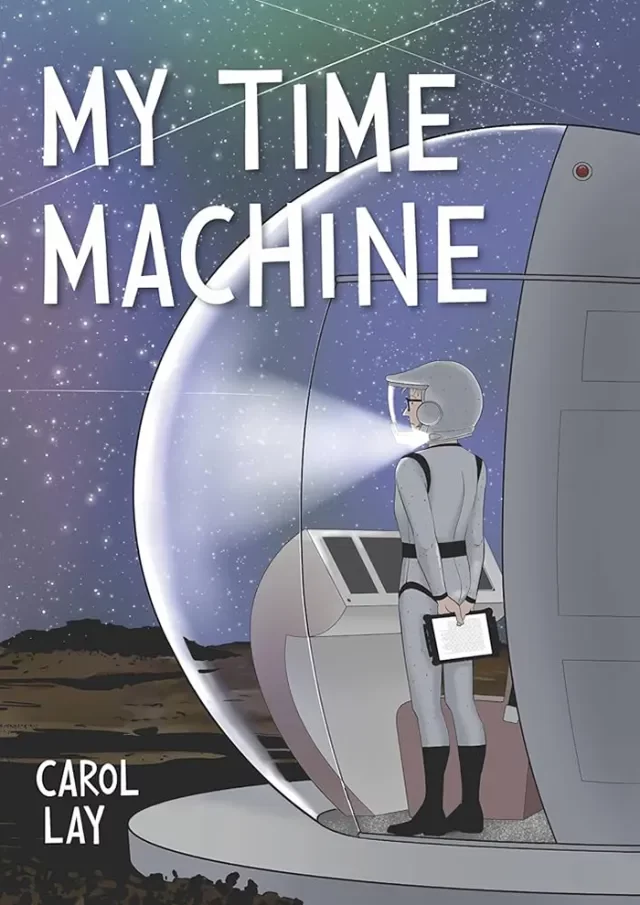

The title of Carol Lay’s graphic novel should remind the reader of H.G. Wells’s book The Time Machine, a work Lay references repeatedly throughout her work. Her unnamed narrator, though — who shares a number of similarities with the author — sees Wells as writing nonfiction; there’s even a reference to the movie adaptation as a documentary. Lay’s narrator follows in the footsteps of Wells’s time traveler, as she goes a few short jumps into the future, then to the time when he meets the Eloi, then to 30,002,020 AD. In the same way that Wells uses his novel to comment on the struggles of his generation, Lay uses her time traveler’s experience to talk about climate change, political instability, and the dangers of surveillance technology.

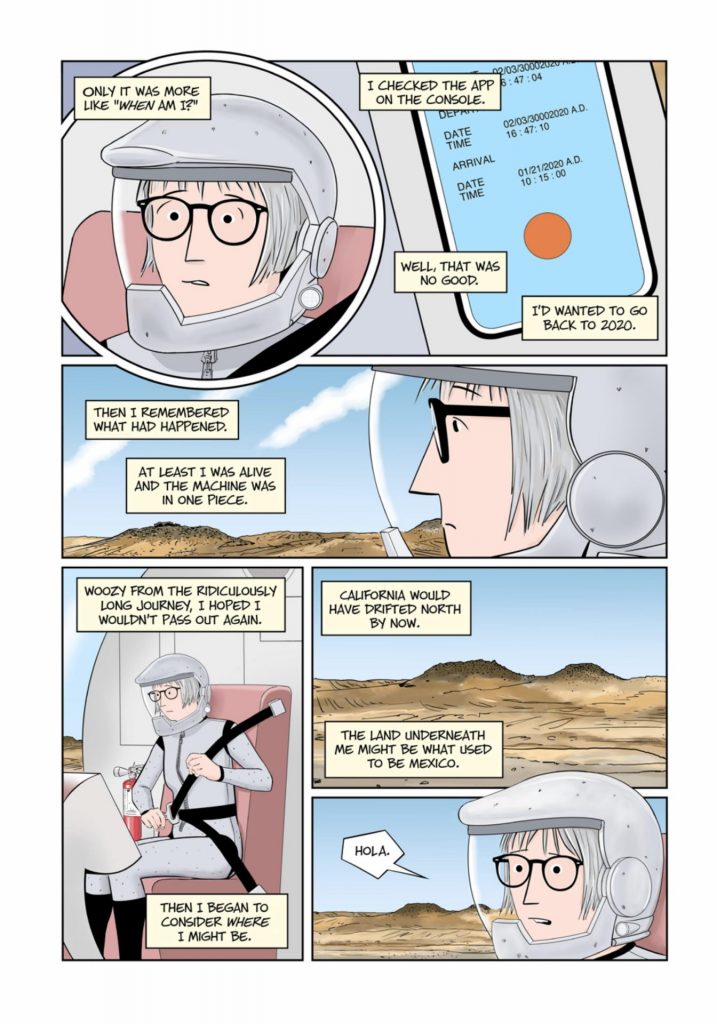

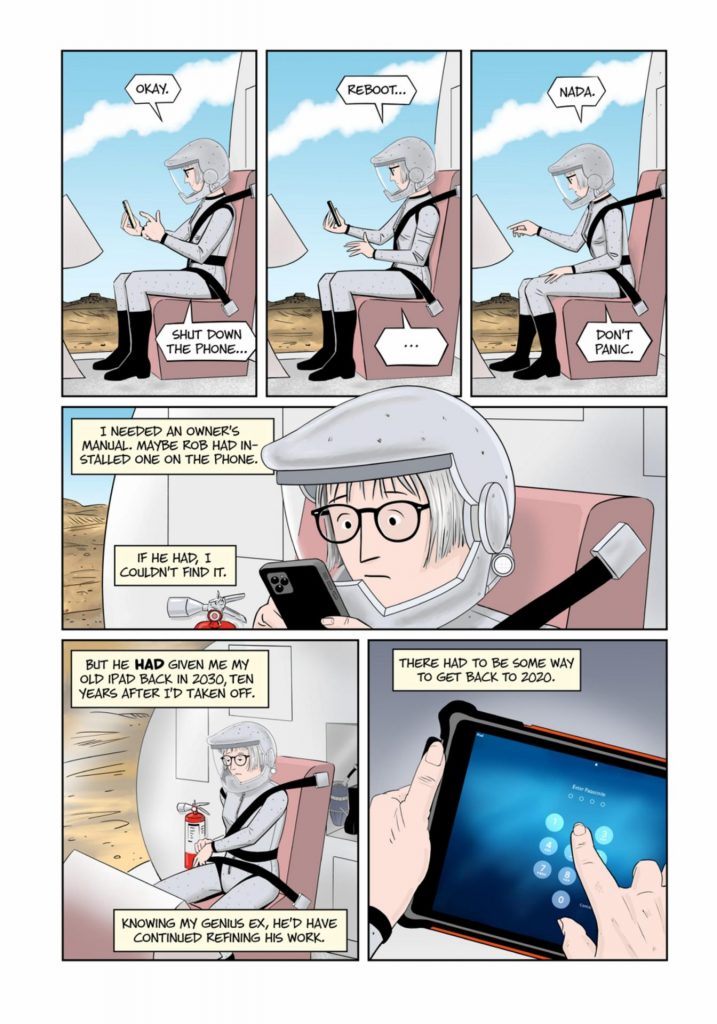

Lay begins with her time traveler in thirty-million AD, seemingly stuck there, as the time machine has ceased to work. To pass the time, she writes her story on an iPad to tell how she came to this point. As with any good work that includes time travel, her story includes some exposition about how time travel might or might not work, including, in this case, why one can’t (or shouldn’t, at least) go back in time and kill Hitler. All of this commentary comes through the narrator’s conversation with Rob, her ex-husband. He’s a physicist at Stanford who built the time machine based on designs from Wells’s time traveler; the narrator inherited the designs from her uncle, who won them in a card game with the time traveler’s grandson’s attorney. However, within that exposition, Lay sets out the clues of what is to come when her narrator jumps into the future, as there are references to COVID (it’s 2020), Trump, and climate change.

When the narrator begins moving forward in time, the reader begins to see those references play out in detrimental ways. She arrives in 2035 to find a climate that is much warmer, with Rob still wearing a mask to avoid infection from new viruses released from melting ice caps. He’s also growing much of their food inside, given the political instability and brutal heat. Most importantly, though, he references mappers, a drone-like machine that used to hunt for migrants, but now surveils everybody. Lay’s version of 2035 takes a variety of issues from our current society and plays them out to their logical extremes, leading to a dystopic society that is simply trying to survive. When the narrator comments that she should just return to 2020 because “Everything here is so…wrong,” Mara, Rob’s girlfriend, replies, “We’re the frogs that got used to the rising temperature. You just got tossed in boiling water.” That reply sums up, on one level, what Lay is doing in this work. She wants to toss the reader into the boiling water to show them what could come if humanity doesn’t deal with the problems that are already present in our world.

Lay takes a similar approach when her narrator jumps all the way to 802,701 AD, the time when Wells’s time traveler encounters the Eloi and Morlocks. Wells uses the Eloi and Morlocks to represent ideas of class, as the Morlocks are the supposed descendants of the working class who have now developed into underground dwellers who run the machinery that powers the world the traveler sees when he first arrives, an almost Edenic paradise, while the Eloi have descended from the aristocracy, but have deteriorated in both physical and mental fitness, possibly because of the lack of challenge in their lives.

In Lay’s future, though, there aren’t any people, though there seems to be a good deal of wildlife. What the narrator first believes to be birds, though, turn out to be mappers, the drone-like creatures from 2035. While people haven’t survived whatever has happened in the intervening centuries, mappers now dominate the world. There may be people, as there’s a shrine to mappers (much like the Sphinx in Wells’s novel), which could imply that there are people underneath it that make the world of the mappers possible. If so, Lay could be reminding readers that we’re ultimately behind the technology we create, especially the technology that watches people. If there aren’t people, then she’s in the line of writers who see technology as taking over the world, having moved beyond the need for humans. Either way, the mappers prevent Lay’s narrator from exploring the world further, forcing her back to the time machine.

Given that nature has returned, though, Lay makes clear that the world will recover from climate change, even if humans don’t. In fact, part of the time the narrator is in this future, she’s watching videos from 2020 that Rob uploaded to her iPad that clearly show a connection between COVID, the mishandling of that and more by President Trump (whom she never names, but clearly references), climate change, and the future she currently sees. The narrator clearly ties those events all together as a warning for the reader of what could come if humanity doesn’t act differently.

While the outlook for the future is dim, the artwork is crisp and clear throughout, as it’s obvious this book is the work of an artist who has been working in the field for years. The nearly two decades of Lay’s comic strip Story Minute (which became Way Lay) have helped her hone her skills, leading to this work. Her lines are crisp, and the colors are bright, with detailed backgrounds to help set the scenes of the various times the narrator visits. The scenes depicting conversations between characters work well, but her artwork truly shines when portraying nature and the cosmos, often breaking out into full-page spreads of galaxies and celestial bodies moving through time.

At one point, when she’s advancing to the far future, she can see the Milky Way, and she reflects on the lack of civilization (no light pollution, which enables her to see it more clearly). That leads her to a reflection on humanity, especially the benefits and joys of science and art. She thinks, “The first priests may have been mathematicians, those who could predict astronomical events. Science would have seemed magical to the uneducated. And the artists who painted the animals in the caves—were they also holy?” Lay is not naïve enough to believe that humanity can science itself out of the trouble we’ve put ourselves in (there’s a brief reference to Matt Damon in The Martian), but she does recognize the sacred nature of both science and art. At our best, humanity can create beauty and wonder in the world, which is one more reason to mourn the lack of initiative to save our world and our species.

That care and concern for humanity comes through in The Time Machine, as the narrator and Lay both want to issue a call to action to prevent the future they see coming. In the same way that Wells wanted to draw attention to the concerns of 19th-century England, Lay wants to warn readers that we have our problems that need solving, as well. While the narrator jokes at one point that cartoonists can’t do much to change the world, Lay is doing what she can to help move us all in the right direction.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply