“In any dispute, the intensity of feeling is inversely proportional to the value of the issues at stake.”

Charles Philip Issawi

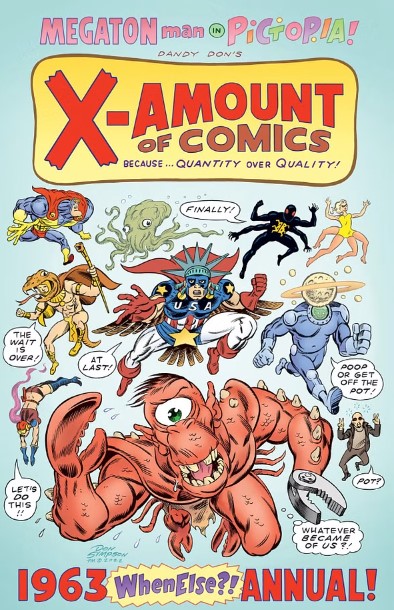

I guess it’s time for independent comics to have its own reckoning1 with Alan Moore. The big two, but especially DC, have spent the last forty years in an endless conversation2 with works of Alan Moore, often manifesting in an interminable string of projects3 that often end with the conclusion that, really, Watchmen wasn’t all that great when you think about it. Exciting. Also, please buy pre-Watchmen, post-Watchmen, alt-Watchmen, and Watchman, our new leading title. Now Don Simpson, he of Megaton Man fame, has his own swing at the bearded one with confusingly-named X-Amount of Comics: 1963 (WhenElse?!) Annual, an unauthorized4 sequel to the never-completed 1963 mini-series. This is the point in which I am probably meant to give you context into what 1963 is all about, why the feelings on it run so high, and what place it represents in both Moore’s career and general indie comics scene of the 1990s.

Except… I’ve never read 1963. It’s never been reprinted or collected you see, not surprising for a story with no proper ending whose owners are still sore at each other. Back-issue bins haven’t really been a thing where I was born; you were lucky to find a five-year-old issue of Spider-Man, never mind anything slightly older or more esoteric. By the time I was made aware of it, and gained the ability to find all these lost issues on the internet5 I didn’t feel any particular urgent need to go and find it. I’ve already read Watchmen and Supreme and Miracle Man6 so another jump into the Moore superhero pool wasn’t on the horizon, especially as Moore’s non-cape stuff, from Providence to From Hell became more alluring.

So I come into this thing pretty cold. And I‘ve left it even colder.

The last thing the comics world needs is more comics about comics. This field is small and insular enough as is, and when our main topic of conversation becomes ourselves it’s the most pathetic sort of ouroboros. At least when movies talk about movies you can have the excuse that it’s a multi-billion dollar industry staffed by some of the most recognizable people in the world, not a couple of folks in Spider-Man t-shirts airing out grievances. Granted, Alan Moore is the last person who can complain about this sort of treatment – not only did he engage in it plenty throughout his long years in comics, but even after leaving the form (for the last time, I swear) he couldn’t quite let go. His “What We Can Know about Thunderman” novella, part of the recent fiction collection Illuminations, is probably indecipherable without a BA’s worth of knowledge in the minutia of superhero comics history7. This fits squarely as part of the general trend in Moore’s latter work towards the comics as thesis, which also means the comics-as-homework8.

People who live in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones. Unless these houses are made of bulletproof glass. And Moore’s house (I have now outstretched the metaphor more than Simpson stretches some of the gags in this book) is made out of glass that can withstand nuclear weaponry. Alan Moore isn’t a perfect man or a perfect writer9. From the racial politics of League of Extraordinary Gentlemen to the way he treated some of his collaborators to the fact that Violator vs. Badrock exists, he has his faults, like everyone else. Unlike everyone else, Alan Moore is a pretty good writer. Which means “What We Can Know about Thunderman” shouldn’t work, but does anyway. He can overcome the inherent weakness of the concept, even the fact that it is obviously score-settling, because he’s good enough.

This isn’t some magic wand Moore wields, this is the result of his writing philosophy10 – which means he gives a degree of depth even to characters that are meant to be caricatures of people he obviously dislikes. I’m thinking of The Merchant of Venice here, a play written from an obvious anti-Semitic point of view that sees the Jew’s loss of his own religion as a reason for a celebration; and yet Shakespeare was such a good writer, someone with an inherent ear for people, that Shylock’s self-justification works. Shakespeare probably was an anti-Semite, but he still wrote his Jew antagonist as a human being. Likewise, the Stan Lee-stand-in in “What We Can Know about Thunderman” is a pathetic figure, but written with enough conviction from his own point of view, that we can understand him. We can accept him. Even as we recognize Moore is having too much fun at someone else’s account.

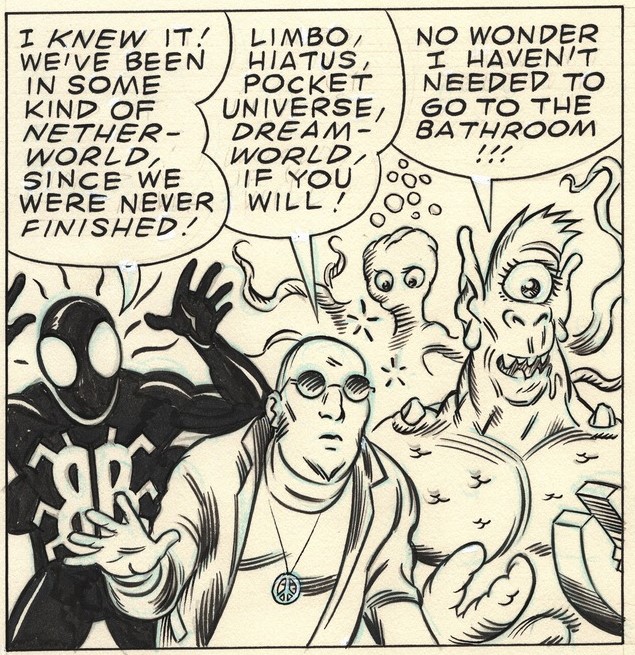

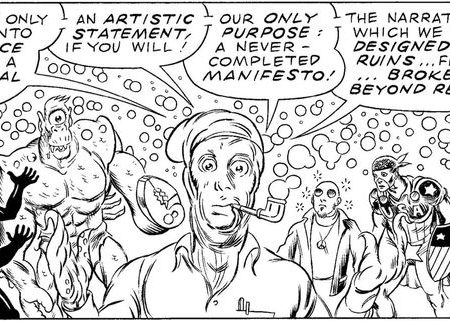

Don Simpson, at least according to this comics11, can’t get out of the shadow of his own rage. X-Amount of Comics’ vision of Alan Moore, named “Paul Nebisco” is as two-dimensional as the art; he presents himself as a genius, living off the work of ‘real’ comics artists while enjoying the rich money of movie and book deals. He’s every negative stereotype of Moore that you see in any internet discussion whenever someone dares to offer the opinion that maybe the man has been mistreated by big comic companies. That maybe he has a right to be bitter about certain things.

There’s no depth to Simpson’s presentation of Moore. Which… fine, comics have a proud history of flattening one’s opponents, from Destroyer Duck’s “Booster Cogburn” to the Fourth World’s “Funky Flashman.” These comics, however, did something with caricatures. They made jokes, they stretched the concept in a visual manner. Heck, the names were puns12. Not the best of puns, but they were something. There’s nothing to Simpson’s parody of Moore; he’s just standing there, mumbling.

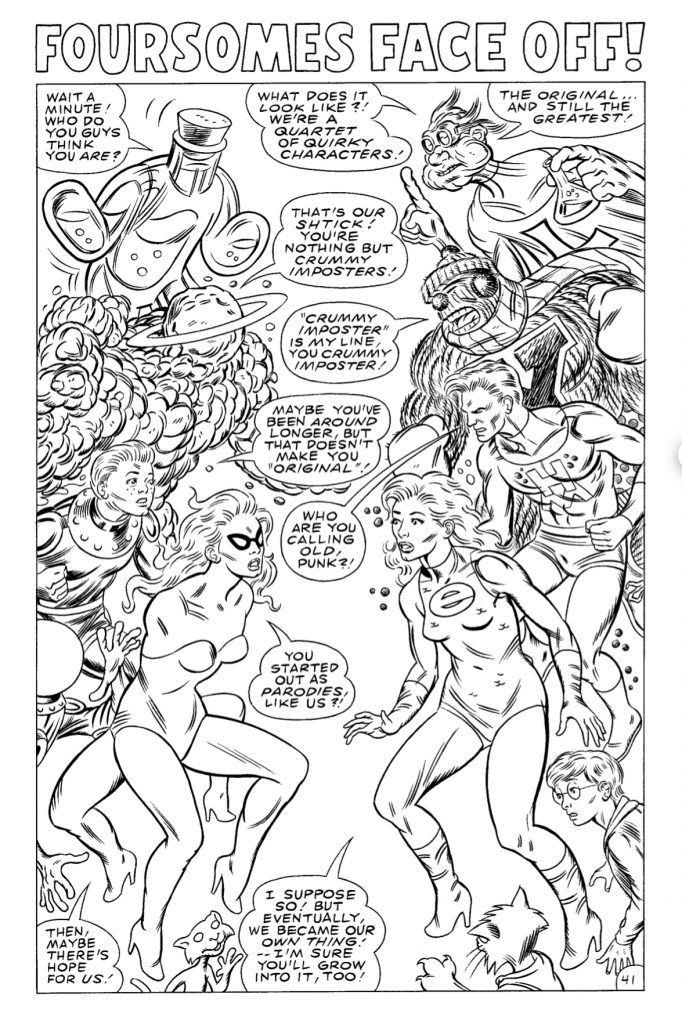

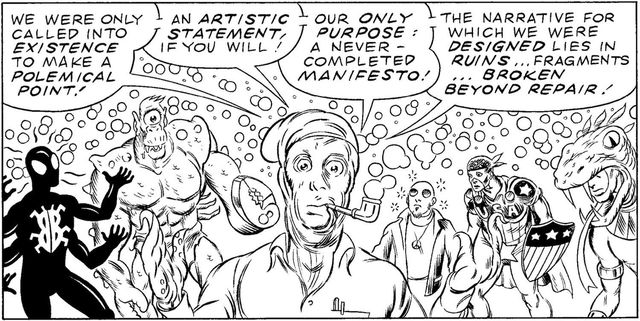

Likewise, there’s no depth to any other aspect of this comic. A confused mélange of 1963, “In Pictopia13” and the continuity of Simpson’s own Megaton Man. It’s like those latter seasons of Venture Bros. in which the humor gave way almost entirely to the constructed continuity of the universe: What If… Roy Thomas did his Fanboy Shtick with 1980s alt Comics? no one asked, but now we know.

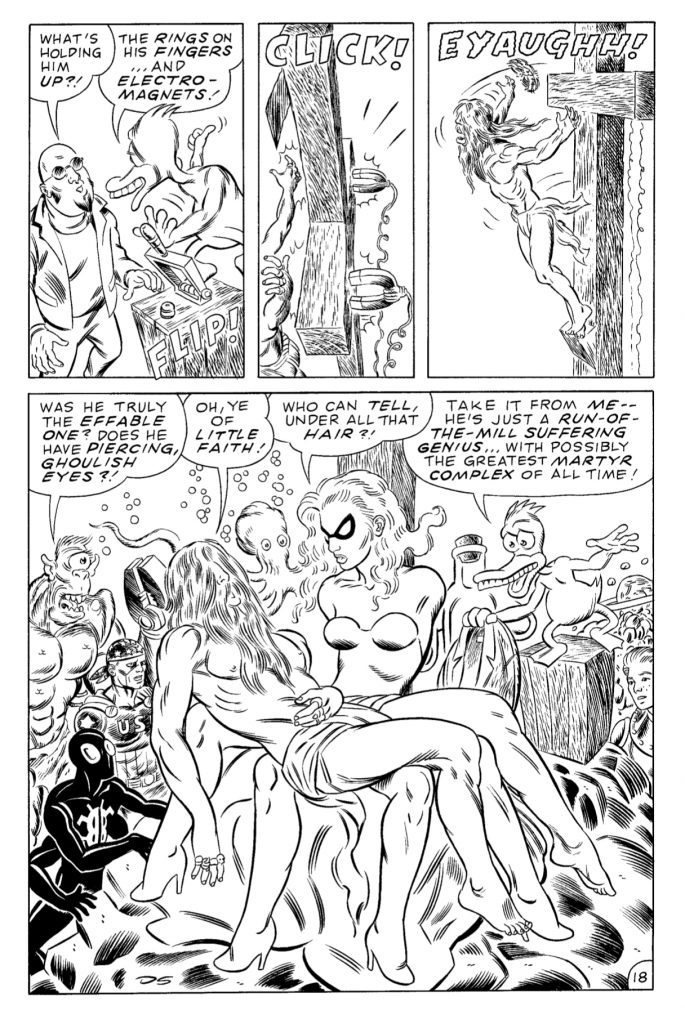

The flatness of the storytelling is also mirrored in the art. Simpson can still draw, and there’s something impressive about the near Sergio Aragonés number of characters he crams into some of these panels, but I can’t help but compare his work here with the early Megaton Man comics. Those stories also tended to be a confused mes, in terms of scripting, but they were interesting and fun to look at. They had differing textures and a sort of Wally-Wood-on-Mad-Megaine wildness to them: characters and backgrounds shifted and turned with every page, reflecting both the changing moods of the story and the different gags Simpson was going for.

At his prime Simpson was, like all good gag-makers, an extremely agile artist, comparable to someone like Kyle Baker in the stretchiness of his line. Megaton Man could express itself through visuals alone, and what it expressed was a sort of throw-everything-at-the-wall attitude towards comics-making. Not everything stuck, but enough did. X-Amount of Comics is almost singular in its tone. The lack of coloring doesn’t help, but, even if Simpson took the extra effort to color himself, I don’t think it would help. There is no texture to these pages, there’s no tactile feeling to any of them. It’s a bunch of well-rendered figures floating in white space.

Simpson occasionally stretches himself, a page composed of only silhouettes14 for example, but mostly one page is much like the other. The ‘story,’ such it is, progresses, but nothing much changes. It’s a pretty short comic overall, but, seeing as it contains only one note, it might as well be a thousand pages long. It’s a dull slog of comics; one so obviously uncertain in its own statement that it ends with both a long afterword and annotations15 explaining several historical fictional figures throughout the comics16. Because jokes are best when you have to explain them.

Did I spend too long talking about Alan Moore instead of the creator and subject of X-amount of Comics? Congratulations! Now you know how I feel after reading this. This comics’ attempt to banish the spirit of Moore, stake the author’s own claim on comics history, only helps to strengthen Moore’s place in the discourse. Even after retiring people still can’t help taking aim at him.

Not since Robert Green took a swipe at a certain ‘upstart crow’17 has an artistic battle felt so one-sided18. Not because Simpson is untalented, a look at any of his older work would prove his artistic worth, or because Moore is beyond reproach – but because the very nature of the story seemingly drains Simpson of everything that made him decent. This would’ve been better as an angry blog post or an article in something like TCJ. As a work of art, a work of comics art, X-Amount of Comics is empty and vacant as the worst of the post-Watchmen work made by the dregs of cape-comics. Which is, if nothing else, some kind of a unique achievement.

It simply proves what has been proven time and time again. The best way to ‘get over’ the influence of Alan Moore on the industry and medium, be it negative or positive, is to do your own thing instead of coming back to that old well19. Leave 1963 where (and when) it always belonged – in the past.

- ‘Reckoning’ here is used in the classic comics industry meaning – ‘making profit of’

↩︎ - ‘conversation’ here is used in the classic comics industry meaning – ‘making profit of’

↩︎ - Usually with the words Geoff Johns somewhere in the credit box

↩︎ - Though Simpson is, at least partly, an author on 1963 – being the original letterer.

↩︎ - In a perfectly legal manner, of course,

↩︎ - Talking about hard-to-get never-completed (at the time) stories

↩︎ - Not just the genre, bet the people involved. This is a book for someone who enjoys reading old Comics Journal letters columns

↩︎ - As someone with more than a passing knowledge of both Lovecraft and Victorian fiction both Providence and League of Extraordinary Gentlemen still demanded the assistance of professional annotators to partially parse out. ↩︎

- X-Amount of Comics seems to assume that all of Moore fans think of him as unfillable demigod. ↩︎

- Moore’s Writing for Comics is still available and highly recommended even if you have no intent to write for comics ↩︎

- I haven’t read a lot of Simpson, so I don’t venture to make a judgment on his work as a whole. ↩︎

- Already the lowest form of comedy. ↩︎

- Simpson sure wrings a lot from the fact that he came-up with title of that story; as if the fact that he drew the thing, and drew it well I might add, isn’t enough. It’s weird to see an artist surrendering so wholly to the cult of the writer.

↩︎ - Which also houses the one amusing gag in the whole affair. A reference to Shadowline, naturally.

↩︎ - In one particular eyebrow-rising moment Simpson ventures forward the notion that Megaton Man #5 is a vital influence on Watchmen. Which just might be the second funniest gag in the comics.

↩︎ - Though I cannot imagine any single person buying this comics that needs to be told who Jack Kirby is. ↩︎

- Or since Frank Tieri tried to do a response issue in his Wolverine run to that Garth Ennis Punisher issue in which the Canadian mutant gets run over with a literal steamroller. ↩︎

- I would insert the ‘I don’t think of you at all’ meme if this wasn’t such a respected venue. Also, if nothing else, Alan Moore proves he still thinks about the comics industry too much. ↩︎

- Be it Watchmen, 1963 or Miracle Man. ↩︎

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

[…] Dave Sim & Gerhard: The Last Day (2004) Josh Simmons: Le Manoir (2007) Don Simpson: X-Amount of Comics (2023) Lars Sjunnesson: Natacha (2022) Art Spiegelman & Françoise Mouly (red.): Raw, Volume 2, […]

For a much more thoughtful reflection than this POS: [link removed]