I’ll start this by stating the obvious: Domingos Isabelinho knows far more than I do about art. It’s not a worshipful statement or a self-effacing one, but a recognition of mere design: his vocabulary, accumulated over (naturally) decades of writing on comics and on art, is dizzying, and he knows it, never hesitating to use it as his strongest weapon. I don’t say this as condemnation, either, but as a source of appeal: this knowledge is a demonstration of hungry curiosity as an antidote for stagnation.

The back-cover copy of The Reading Gaze: “My Comics,“ the 2022 collection of writings by Domingos Isabelinho published by Chili Com Carne and Thisco, predicts, with Isabelinho’s usual wit, its own critics:

I like comics, I just don’t like the same comics you like. This is the genesis and explanation of this book’s subtitle, ‘My Comics.’ On the other hand, if you insist that I don’t like comics because what’s in this book are not precisely cartoonists, don’t worry, I like them too, they’re just not here yet because I divided the comics corpus in two: The Extended Field and The Restrict [sic] Field. This book is, then, an anti-essentialist stance, a cry of freedom from India Ink [sic] on board, if you like…

It’s not unwarranted, per se; this back cover is complemented by its front counterpart, adorned with portraits by Picasso, Masereel, Goya, Dix, Bacon, and Hokusai: six artists, yet not even one would fit the traditional label of “comic artist.” Over twenty-two essays, some published on his own blog and others in well-esteemed publications all over the world, Isabelinho delves into the theory and practice of sequential art, with a not-so-subtextual advocacy for a richer self-education in wider spheres of art. It’s not an unwelcome cry—one of the most prominent results of the corporate subsumption of culture is a self-referential, which is to say self-absorbed, pool of inspiration, and Isabelinho tries, in his own way, to fight that; he is combative, sometimes downright hostile, but his heated passion comes with an articulatory edge: he will always clarify and back up his arguments, leaving the reader no choice but to thoroughly understand the point he’s making (even if they disagree with it). He knows why a thing works or why it doesn’t, and, God as his witness, he will tell you exactly why.

Some of the pieces in the book are more meticulously constructed, while others, clearly written for self-publication, betray a certain headiness, feeling more like vignettes than proper essays; they are, perhaps not coincidentally, less critical, so as to say “hi, here’s something I like, let me talk about it for five minutes just to get it out of the way.” There’s something of a lack of external editorial perspective at play (as well, I might add, as a lack of proofreading, although the result of that is a hindrance more to the eyes of pedants like myself than to the actual argumentation), owing perhaps to Isabelinho’s stature and “brand” giving something of an enhanced license for shorthand.

Still, the core of the book and the essays contained in it is sound—his essay refuting the oft-touted argument of uncritical stereotyping as “products of their time” is incredibly effective, completely and almost casually unraveling both Eisner and Crumb in under ten pages of text, and the preceding piece on Martin Vaughn-James’ The Cage (as reviewed by yours truly for this esteemed publication) is a gorgeous analysis of an alienatingly-brilliant text. No matter his headiness or textual hostility, he leaves you no choice to recognize: the man knows art, and he knows comics.

The problem starts when he tries to present the two as one and the same. In another recent essay, for another outlet, on another (if adjacent) subject, I quoted the following passage, from The Expanded Field of Comics and Other Pet Peeves: The Origin’s Myth (included as the second essay in the first part of the book, Comics Theory and Criticism):

All art is based on experiment. The most inventive artists are always pushing the limits of their art forms. Comics are no exception, but if we put a formal corset around them what happens is that: (1) we lose some very important artistic achievements (some of those who defend comics exactly because they are mass art could not care less, obviously, but I, for one, do) and (2) we seriously limit the creativity of the artists who chose to create comics.

It’s a great piece of writing, that rings true entirely; it also, in its little parenthetical, demonstrates Isabelinho’s penchant for only-semi-playful hostility toward a mass-art/pop-cultural readership that does not ignore him so much as completely avoids awareness of his existence (I don’t think it would be too elitist to assume that the average reader of the latter-day Comic Book Resources listicle would have no reason to read Isabelinho talking about Francis Bacon, although perhaps this only demonstrates my high bar for elitism). And yet his rejection of a strict definition, while completely correct (in my opinion), is replaced by a totality of the loose, a sort of anti-semantic all-encompassing signifier that approaches a critical degree of dilution. While I have spoken in the past about the inherent infidelity of signifier and category, Isabelinho’s opposite approach risks eliminating all common semiotic ground by rendering all ground common.

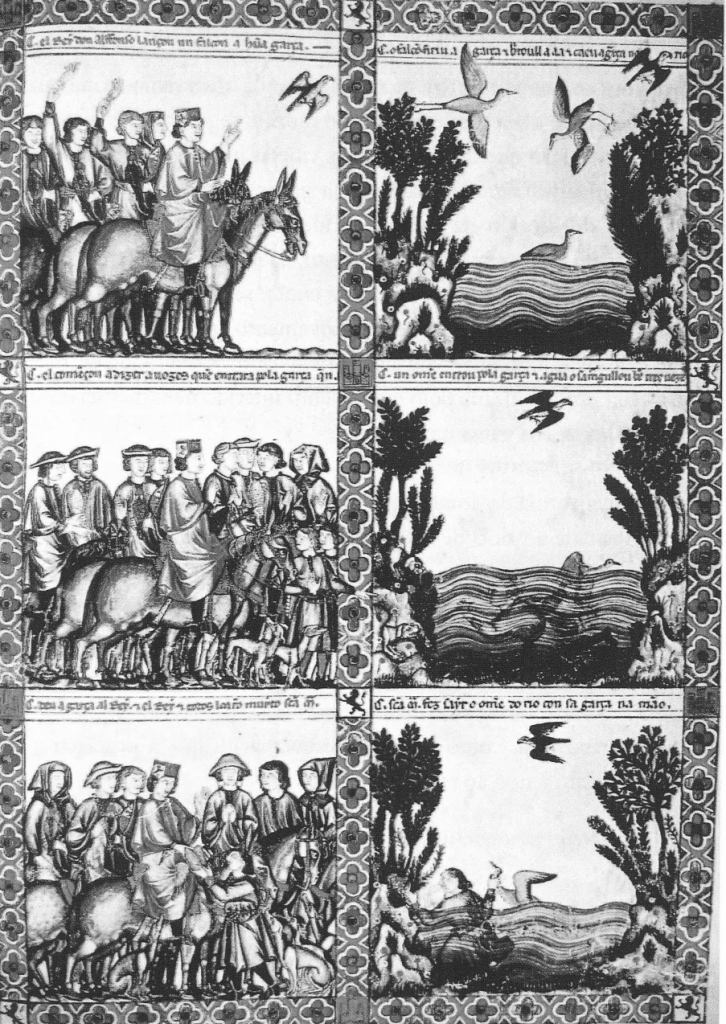

Isabelinho scrutinizes (and rejects) the McCloudian tendency to claim works as “comics” in retrospect as an attempt to elevate comics from pulp to pearl, yet stretches the umbrella of “comics” in a similarly all-too-wide manner, claiming illuminated manuscripts and Pablo Picasso with the same ease as Eisner or Kirby, in a manner comparable to a man who breaks down walls to make his own room bigger instead of recognizing that there are other rooms that can be utilized on their own terms.

Consider, for example, a work Isabelinho does not mention (I don’t know if it is on his radar at all): French-American artist Guy Buffet’s series of “cinematic” paintings, which he began with The Making of a Perfect Martini. It’s a beautiful painting, ecstatic in its dynamism and passion, whose sequential nature is, as demonstrated by its twelve panels, self-evident. Yet is it, strictly speaking, a comic? I rather wholeheartedly contend that it very much is not.

You may say that it has all the formal characteristics of a comic, and you would, indeed, be correct; I would venture even further as to say that were this published, as is, by Epic Comics, say, or else Fremok or L’Association, its status would change as rapidly and as eagerly as the turning-on of a lightbulb, rendering my argument, at least on its surface, as completely arbitrary. And yet that, to me, is precisely what makes a sequential work a comic: the artistic context in which it is crafted, the works with which it is engaging and following consciously. The form of “comics” may (and should!) be a wide and malleable one indeed—a Batman devotee similarly may not view The Cage by Martin Vaughn-James as “comics,” and I may even be amenable to this disqualification depending on how compellingly they may back it up—but there is a degree of cultural lineation that strikes me as necessary.

The retroactive claiming of certain artists may be not only satisfying on a cultural-historical level but even formally fitting as well—indeed, “The Canticles of Saint Mary” to which Isabelinho dedicates an entry may well function strikingly similarly to a comic, with its marriage of diegetic calligraphy and sequential imagery—but a formal function does not necessarily correspond with a real-time cultural function. The Canticles, and similar illuminated manuscripts, did not have a past (or present) culture of comics per se to consciously engage with; their tradition was that of religious art, not of comic art, in the same way that Guy Buffet’s painting is not geared toward commenting on (or within the space of) comics, but toward an existence in the contemporary fine art spheres. It’s this claiming, too, that tends to nullify Isabelinho’s own argument on experimentation versus “corseting”: the experiment is always contingent on innovation, on the novelty of the potential results (or the lack of novelty in the results’ reinforcement of common assumptions). If you look through Isabelinho’s ultra-wide cultural lens you will almost invariably find someone, in some sphere, to have attempted the same formal effort that you consider experimental. That’s the thing about novelty: it depends entirely on how hard you look.

To me, the definition of what constitutes a comic, what distinguishes it from the larger category of sequential art, revolves around the work’s intent of function, be it stated outright or plausible/presumable as derived from existing statements by the artist. Artists like Hokusai or the authors of the Canticles did not have the cultural vocabulary required to define their works as “comics” as such, simply because what we now know as comics did not exist yet. It is much more satisfactory to me, in such cases, to make the distinction between the modern comic and the sequential word-and-image artistry that preceded it; you may even call it a “proto-comic,” if the word “comic” must exist in the phrasing. Other artists cited by Isabelinho, such as Francis Bacon, were very much alive to witness the existence of comics as we now know them, but did not, at least so far as I can tell, seek to engage with them in any way, despite incidental overlaps of formal language. Picasso at least had an active interest in comics, as a reader and an occasional cartoonist, except Isabelinho, instead of remarking on this connection, opts for works of a categorically divergent nature, with different preoccupations in mind.

Whether you like it or not, “comics” are a cultural category as much as they are a formal category, which allows for the malleability that Isabelinho is such an ardent advocate for: we can all agree that Heathcliff is a comic in spite of its extradiegetic dialogue and its lack of sequentiality (at least in the daily strips, which, one may immediately notice, are still categorized as “strips”), because it serves a close-enough cultural function.

It may strike some as semantic pedantry, but, to me, the framing speaks to a larger question of whether or not the category of “comics” is entirely synonymous with “sequential art” or merely included therein; to claim the former is anti-evolutionary, an end-of-history viewpoint that threatens to subsume through the momentum of sheer expansion, whereas the latter is a humbler attempt to recognize limitations. Is it not more true to fact to acknowledge that we are but a link in a long evolutionary spine chain of artistic discourse that has long preceded us and will long outlive us, and that the instance we now consider the default is just an instance?

What I find notable, too, is that The Reading Gaze focuses exclusively on the works that come decades if not centuries before it, with little regard for the more recent past (not to mention the present, that most mercurial and overtly fictitious chronological construct). Isabelinho demonstrates a great interest in the evolution of comics, yet that evolution appears to come to something of a total halt. I do not claim to know his day-to-day reading habits, but the curatorial selection indicates, to me, a perception of form that may not have a starting point but certainly tends toward an ending point, which is, in its own way, a shame, in that it partially undermines that aforementioned hungry curiosity that lies at the heart of his appeal.

The subtitle of The Reading Gaze is accurate: these are, after all, only Isabelinho’s comics. His definition varies from mine (I suppose there might be more of a conservative rigidity to my arguments than I am used to), and my definition will inevitably vary from some of yours’. In The Origin’s Myth, he writes: “Me?, [sic] I have no definition of comics. I prefer to say with Saint Augustine: If no one asks me, I know what they are; If [sic] I wish to explain them to those who asks [sic], I do not know.” And, indeed, I am in the same bind, if it is a bind at all: I cannot come up with a set of rules that apply to all comics past and future, and I outright reject that idea. But the why of it matters. Where Isabelinho attempts an “anti-essentialist stance” he appears to paradoxically fold anti-essentialism into essentialism, in a map-versus-territory shuffle, leaving one no choice but to wonder: Domingos Isabelinho knows comics, and he knows art—but does he know the definitional limits of either?

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply