“He’s a queer man, Captain Ahab—so some think—but a good one. Oh, thou’lt like him well enough; no fear, no fear. He’s a grand, ungodly, god-like man, Captain Ahab;”

Moby Dick, Herman Melville

“He wasn’t just good, y’know. He was beautiful…unbelievably beautiful.”

Ping Pong, Taiyō Matsumoto

The five-volume series Summit of the Gods, co-written and illustrated by Jiro Taniguchi. (based on a novel by Baku Yumemakura who also gets a co-writer’s credit), is a curious object. On the one hand, it is a sports manga, with all the prerequisites of the genre: a tough and demanding sport (mountain climbing), a protagonist motivated by a singular desire (to become the best in their field), a series of increasing challenges (harsher weather, climbing without oxygen, intentionally choosing a more difficult path to the top). Yet it also lacks a deciding element: there isn’t really a rival. Early on, in the first two volumes, there’s a sense of built-up rivalry, as the series’ focal point, Habu Joji, meets another climbing ace; yet this presence is quickly removed from the ongoing narrative, becoming a memory, a motivator. This is the main point of the series, the thing that makes it unique. Habu isn’t competing against anybody else, his rival is nature itself – he will conquer God’s creation.

There’s a reason I referred to Habu as the story’s “focal point” rather than “protagonist.” The actual narrator, the character we spend most of our time with, is Fukamachi, a photojournalist who pretty much stumbles into Habu’s story. It’s a chance for the authors to engage in a slightly old-fashioned nested-narrative: as Fukamachi’s quest into figuring out Habu becomes entwined with the story of (real-life mountaineering legend) George Mallory, which becomes an attempt to encompass the whole history of mountain climbing, which becomes a philosophical treatise on human will-power and motivation to excel.

It’s pretty ambitious. Reading, devouring, the series I couldn’t help but think about Moby Dick. Partly, it’s the surface elements. Habu’s quest to conquer the white top of Everest (on his own terms) reminds me of Ahab’s desire to bring down the white whale. Fukamachi, introduced early in order for the reader to see Habu’s tale in a slight remove, is playing the role of Ishmael (though he becomes a more significant part of the story and is much less of a wet-blanket). Like Melville, Taniguchi obsesses about researching his project; you can bet your dollar (yen?) that all the tech and equipment is drawn down to the minutia, that characters go to real mountains, use real techniques, and discuss actual challenges and records achieved by various climbers throughout history.

In that sense, Taniguchi is probably the perfect person to tell this story, possibly even more so than the author of the original book. It’s not just his technical skill as a draftsman, or his attention to detail, it’s his interest in people who become entangled in something new and learn to appreciate it. The newly minted manga artist in A Zoo in Winter, the samurai learning the ways of Native Americans in Skyhawk, even The Walking Man, a book as diametrically opposed to Summit of the Gods in terms of the attitude of the characters (it follows a pleasant, mellow, individual who is utterly content with the small pleasure of local life), has, within it, the certain zest for discovery that animates all of Taniguchi’s work.

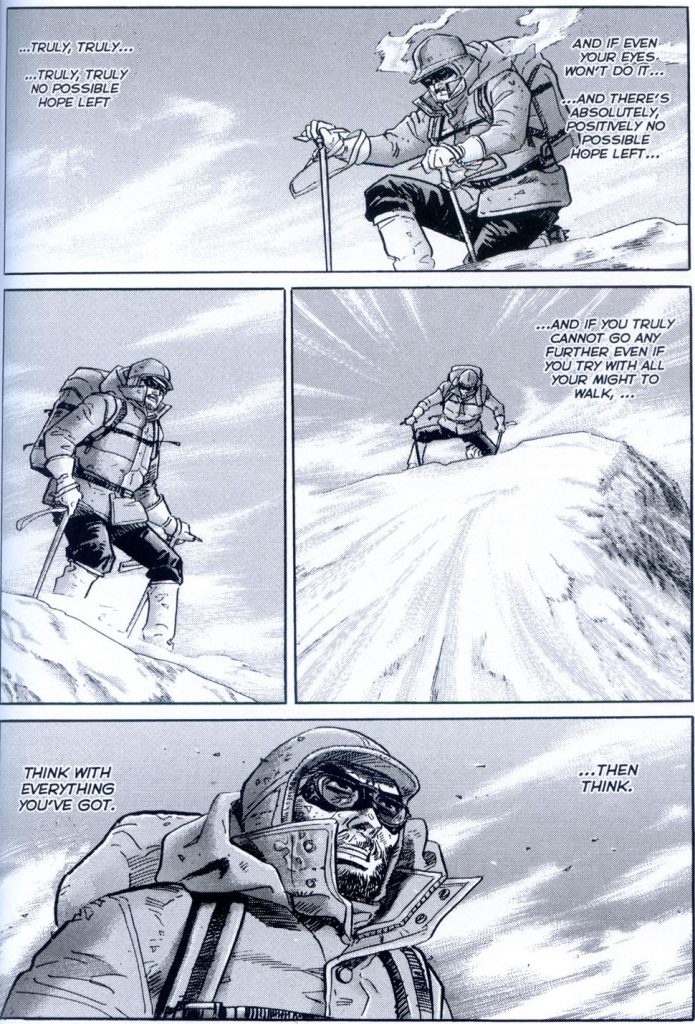

Go to book 4 of The Summit of the Gods, to the final chapter. That great final climb. An impossible act, we are told. Over and over again the limits of human endurance and the exact physical dimension of the act are recounted: the amount of weight the body must carry, the difficulties of reaching above a certain height without an oxygen mask, the way the cold seeps past all protections until it becomes part of you, in your skin, in your bones, in your mind… an environment made to be anti-human, hostile to life as we know it. Taniguchi draws it both realistically, as his normal style dictates, and, at the same time, with the sense of utter alien existence. The protagonists might as well be on the moon. Without space suits. And Habu, somehow, would make it. Even as others falter or tell him that there are concrete limits to what he can do, he will find a way.

Taniguchi’s zest, however, can also be a weakness. The positivist leaning that so befits The Walking Man, the sheer admiration for the human spirit, can feel out of place in Summit of the Gods. There should be something frightening about Habu, about this figure whose outward behavior is as cold as mountains he climbs. Yet Taniguchi never quite manages this emotional distance. It becomes clear to the readers that this is a façade, that beneath the frigid exterior of his Ahab there’s a burning human heart. Can someone be both utterly obsessed with achieving a singular goal while remaining human and humane? Baku and Taniguchi seem far more certain of the answer than I.

Possibly the answer is found in sports manga, a genre that usually positions self-improvement in a particular field with self-improvement as a person (with a few notable exceptions). Becoming a great mountain-climber allows Habu to become the best version of himself that he could’ve been; whatever he cast aside to achieve this dream (a steady job, a regular family, even his own life) was a part of his purification. That is what we see throughout the story, as Fukamachi circles around Habu’s story, a man casting aside everything but his essence. There’s something almost religious about it, for a book whose belief in human willpower borders on atheistic, an act of faith; not in a higher power – but in other people.

With just five compressed volumes, Summit of The Gods might not be overlong in terms of a manga series, but at 1,500 pages it feels particularly epic. The structure of the story, and its attempt at realism, doesn’t leave a lot of room for Taniguchi to deviate from the main plot. He can’t introduce new rivals or reveal some hitherto unknown secret mountains (the type of thing you would find in less-grounded sports manga). This means that when the book does attempt to deviate and introduce further complications, the old camera that kicks off the plot is stolen, a kidnapping plot introduced halfway, a crime boss gets a chapter explaining his backstory, it feels like the authors are grasping for more material to fill in the pages. It’s a damn big book(s), for a story of one dude trying to climb one mountain.

In terms of simple storytelling, Summit of the Gods could probably do with a good trim. There’s a limit to how many asides we can go through before we suspect the authors are just filling up space. There’s a limit to how many times we can be told a person is doing the impossible. To how many shots of a freezing face staring intently at the reader. A limit to the number of majestic peaks Taniguchi can sketch in the background. A limit to the number of shots faithfully rendering ropes, hammers, pickaxes, pulleys, etc. At least, there should be a limit.

But, I remember again. That’s what people said about Moby Dick and still do – the book has been condensed and abridged, mocked for its long-windedness and Melville’s obsession with non-fiction asides about any subject tangentially related to the main plots (several of which have since been discredited). Yet all these things, all the stuff that will get lost in an abridgment (or adaptation) is what makes the book what it is: a Big Book on a Big Theme. Summit of the Gods is also a big book, and it has a big theme; it works hard for it. You can like it, you can dislike it, you might even be bored by it. But touch not a single page or panel – you are in the presence of something sacred, not just a work of art, but an act of devotion.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply