Sabba Khan begins her graphic memoir, What is Home, Mum, with a preface where she presents her image looking into a full-length mirror. She sees a variety of people, including herself, telling her how to tell her story, or even that she shouldn’t tell it at all. She ends the preface by referencing a question her therapist asked her: “What does it mean to belong?” Rather than a straightforward retelling of her life, Khan explores this question using her life as the means by which to do so.

Khan is a second-generation immigrant to the UK, already placing her in a situation where she has to ask what it means to belong. Her ancestors struggled with the question of belonging as well, yet in a different way. Her family comes from Kashmir, the disputed region between India and Pakistan, a region the British created arbitrarily when they divided the one country into two. Her family ultimately left because the Pakistani government built a dam that flooded their ancestral land, moving them to a place where their farming livelihood was much more challenging. Khan finds herself in between two worlds in the UK, but her family was already in between two worlds before they left.

Khan traces the idea of belonging through relatively brief chapters, often beginning with an idea or image that will lead her to wonder where or whether she fits in with her family and culture or with the UK culture where she has grown up (the book was titled The Roles We Play in the UK). For example, she uses her hands in one section to ultimately explore the idea of assimilation. In her family, her culture, and her faith, she uses her left hand for dirty tasks, like “cleaning your bum”, as she says, while she should use her right hand for other tasks, such as giving Shahadah (which she defines as a “declaration of faith”) or eating. When she eats at home, where they eat with their hands, there is no problem with this distinction, but when she is out in public, using silverware, she feels out of place. She wants to eat with her right hand, but she knows she should cut food with the knife in her right hand, leaving her fork in her left.

She then takes those ideas and begins an exploration of acculturation, as she lays out the four methods immigrants often use to try to adapt to a new culture: segregation, integration, assimilation, and marginalization. Khan effectively uses her art to mirror the ideas she’s laying out, as she presents the four methods in a sketch that resembles a Venn diagram with bubbles within the circles, showing how immigrants often feel separated even within particular social circles. She ultimately asks the question, “Will we be able to untangle from the hundreds of years of imperialism and how it shapes our place in this land?” Khan’s use of a basic image that everyone can understand—her hands—and allowing them to become an image through which to understand a much more complicated idea—assimilation—helps a reader (like this one) who hasn’t had her experiences to better understand the questions she’s struggling with.

Another way Khan reflects the liminality of her life is by mixing the cultures of which she is a part. By the end of the chapter on hands, for example, she draws on Audre Lorde’s famous line: “The master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house.” At various other times, she quotes Carl Jung and discusses Schrodinger’s cat, while also referring to an Islamic scholar, Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, who was the first to come up with the idea for what we now refer to as the multiverse. Those thinkers all play a role in how she thinks about her fate (Kismat) and her agency. She is torn between those two ideas, but her attempt to pull from each culture illustrates how she’s trying to shape a self that acknowledges both worlds and brings them into some type of harmony.

A more complicated division comes up as she begins to develop as an artist. She decides to apply to one of the top art schools in the country, but her art teacher tells her she needs to include a sample of life drawing, as that’s one of the requirements for the application. She is unable to tell her teacher she is not allowed/does not feel it right to see somebody else naked, so she is left with the ultimatum of doing such art or not attending a quality art school. Ultimately, she attends a life drawing class and creates what she calls “the most beautiful form I could capture”. It is a large charcoal sketch of the woman, so large, Khan says, it could “carry [her] guilt, so large and magnificent that every time [she] unrolled her at interviews, they’d gasp”. The work carries the guilt she feels at going against her religion and culture, but that tension leads to great artistic work, mirroring the work she’s doing in this memoir.

This tension shows up throughout the art of What is Home, Mum, as Khan will often create images that show her struggling with decisions, with multiple versions of herself in different locations within that art. The most obvious example is an echo of M.C. Escher’s “Relativity” in the chapter that begins with a meditation on mortality as a commonality we all share, but which leads to her meeting Mark, her future husband. He embodies a love she hasn’t experienced, a love that helps her understand the divine in a new way. In her use of Escher, she illustrates how she is, in some way, multiple people at the same time in different places; she’s attempting to combine all aspects of herself, her ultimate goal, though she’s not there yet.

This tension between personal agency and destiny shows up in another important idea that runs throughout the work: the self versus the community. Khan grew up in a large, extended family that valued the good of the group over that of the individual. Her parents were the first to come to the UK, so they often served as a welcoming waystation for those who came after. In her reflection on her childhood, she writes, “Family is not nuclear. It is collective and communal. There is no self here. No individual. If we all take care of each other then no one has to take care of themselves alone.” It’s clear Khan values that idea and her family, but that structure also becomes oppressive, especially when she reveals the ways in which people use that system to abuse others, both literally and metaphorically. Early in the work, she draws herself in tight spaces—under chairs or tables—to represent how she has to make herself small in such situations, which leads to her feeling like she has lost her voice.

British society presents a different view of the self and community, as it values individual agency and choice. She studies Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, which prioritizes self-actualization, as she is beginning to exercise more choice in her life. She ultimately decides not to wear the hijab and to date and marry a white, British atheist rather than the men her father had strongly suggested. However, she learns that Maslow had taken the idea for his hierarchy of needs from the Blackfoot tribe in Canada, changing their ultimate focus—cultural perpetuity—to self-actualization. They valued culture over the individual, but Maslow reversed that focus. Khan tries to live in the middle of such a dichotomy, as she wants interdependence with her family and culture, not dependence or independence.

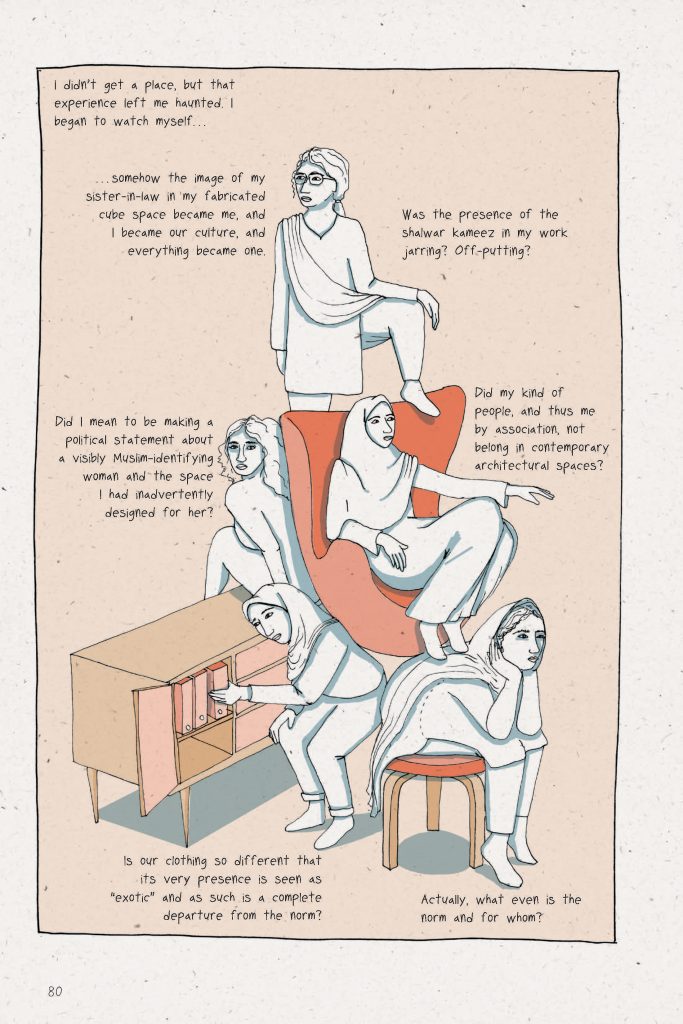

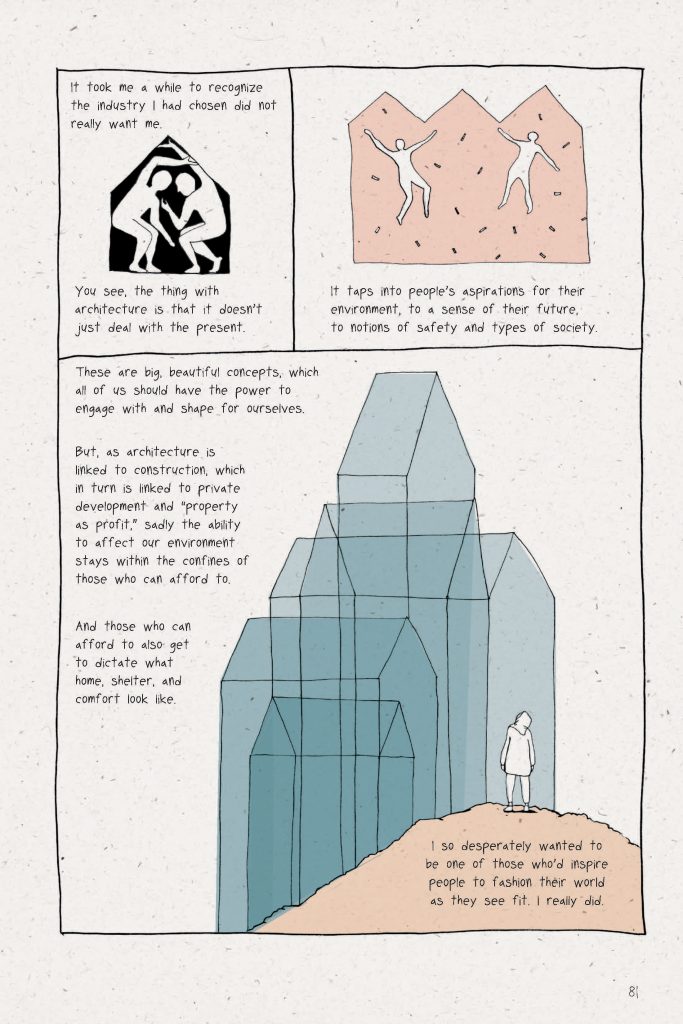

In her exploration of that interdependence, she examines all that keeps her and others from it, whether that’s oppression due to class (in a chapter on the caste system), gender (the systemic sexism within the architectural field), race (she gets spit on when she is a child), or religion (as a woman, she has little voice). She explores imposter syndrome and testimonial injustice (“when a person’s thoughts and opinions are constantly ignored or mistrusted because of their identity”), but she ends the work by looking toward the future, not just the realities of the present. She wonders if she will ever want to bring a child into this world, and she uses a poem by Allama Iqbal (translated by Shay Khan) to imagine a better world. The closing lines read,

Every mirror shatters to pieces

when hurt by stone.

That the stone may shatter to pieces,

search for a mirror that has such power.

She wants a reflection of herself that is strong enough to shatter whatever rocks the world throws at her. She wants that for others as well, as she writes in her afterword, “At first I wanted people to cry with me and share in my pain. Now, I want to give people a window to see into the beautiful complexity of life.” Rather than using her work to present a mirror for Khan to see herself, she has created a window where readers can learn about her life and her world, but also see a different world, one where it’s possible for Khan and all readers to live in the tension between all of our backgrounds and cultures. Through her willingness to explore the complexities of the problems, she provides hope that we can overcome them and live lives interdependent on those around us.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply