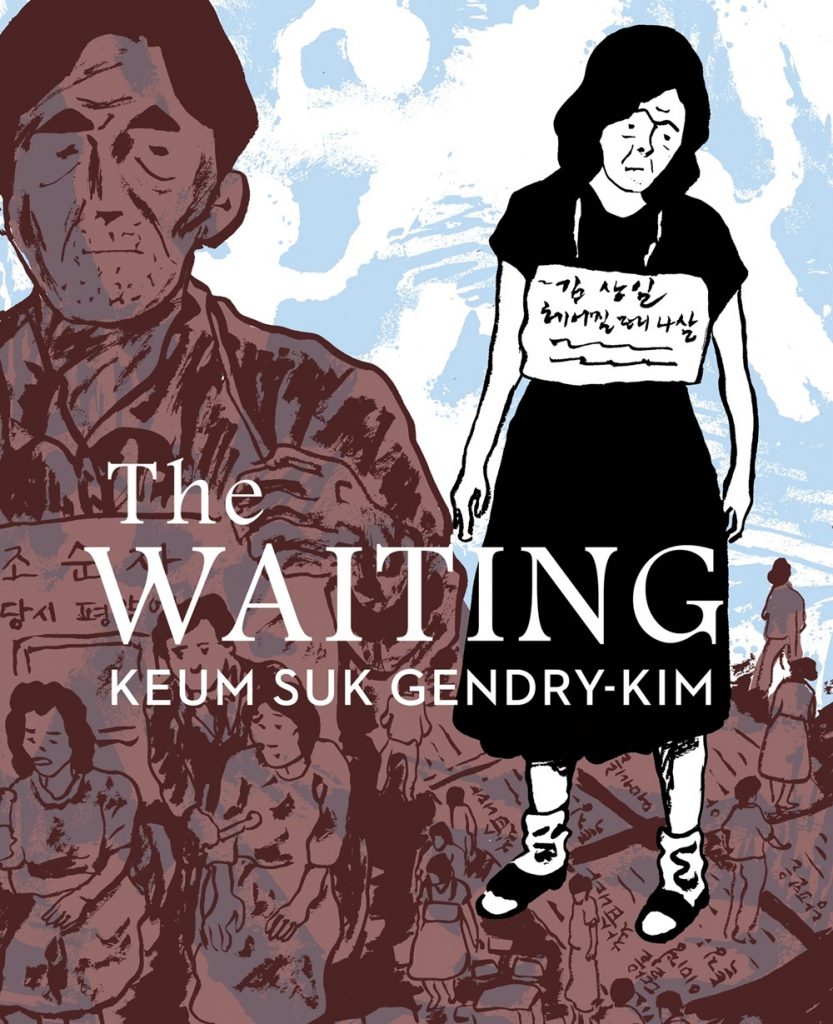

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s most recent graphic novel is fictional, but Gendry-Kim bases it on the historical experiences of so many Koreans who live separate lives due to the war and the barrier between North and South Korea. Gendry-Kim learns that her mother once lived in the north, but had to move south to escape the war, leading to her separation from her sister. She also talked to two people who were able to meet their lost family members, albeit quite briefly. She didn’t want the story to be about any particular individual, so she uses their stories, along with the many others who never get the chance to see their family again, to create her book. The Waiting, among other meanings, is about waiting for the chance to see a family member again.

Translated by Janet Hong

Drawn & Quarterly, 2021, 242 pp.

Keum Suk Gendry-Kim’s most recent graphic novel is fictional, but Gendry-Kim bases it on the historical experiences of so many Koreans who live separate lives due to the war and the barrier between North and South Korea. Gendry-Kim learns that her mother once lived in the north, but had to move south to escape the war, leading to her separation from her sister. She also talked to two people who were able to meet their lost family members, albeit quite briefly. She didn’t want the story to be about any particular individual, so she uses their stories, along with the many others who never get the chance to see their family again, to create her book. The Waiting, among other meanings, is about waiting for the chance to see a family member again.

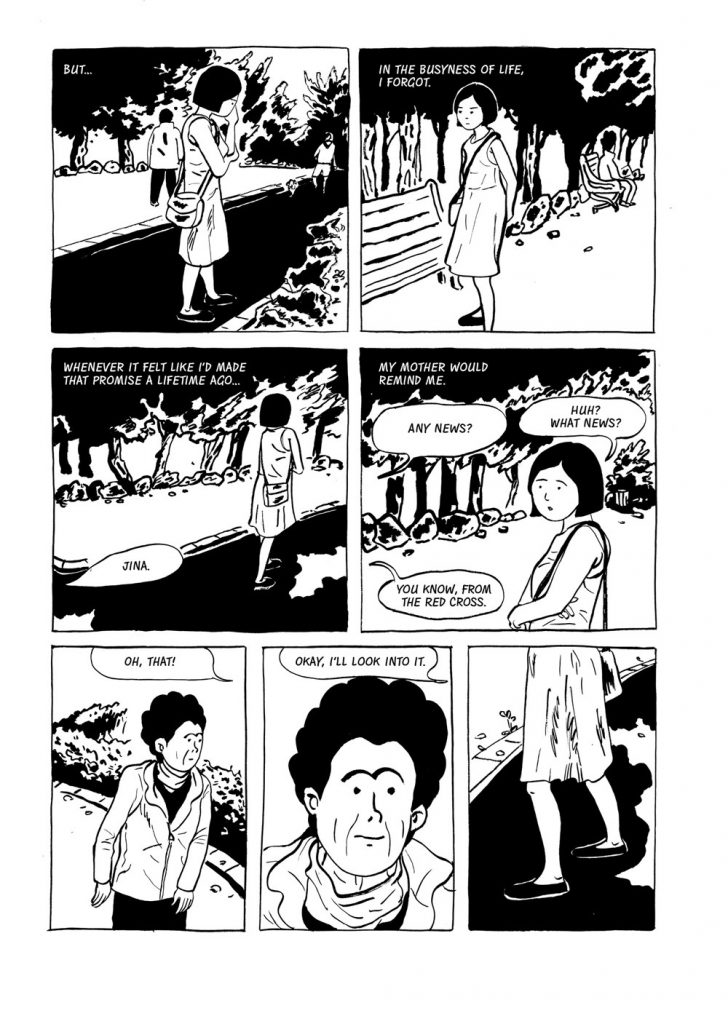

Gendry-Kim tells two parallel stories, one in the present of the graphic novel and one in the past. The present is about Jina and her move away from her mother, Gwija. Jina has lived near her mother for her entire life, and, now that she is nearing fifty, she feels the need for more freedom. She even admits that her concern for her mother has kept her there for so long. The story from the past is longer and more detailed, as Gendry-Kim relates Gwija’s story, moving quickly through her childhood to her marriage and the birth of her two children.

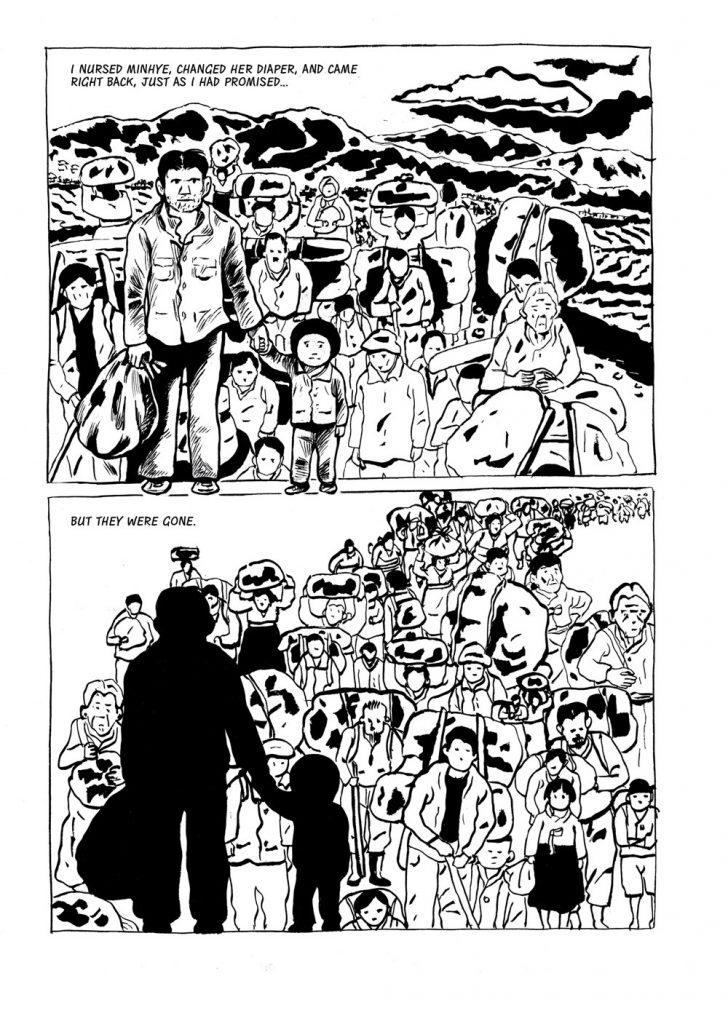

The key part of her story, though, is when the family has to flee to the south to avoid the approaching army of what would become North Korea, led by Kim Il-Sung, but supported by the Soviet Union and China. Gendry-Kim relates the struggles Gwija and her family face as they attempt to save their lives by traveling hundreds of miles in large groups. At one point, as they are walking along the railroad tracks, the Americans even shoot at them. The most important moment of the journey, though, is when Gwija becomes separated from her husband and son, neither of whom she sees again.

The artwork is a stark black and white palette throughout, and Gendry-Kim makes excellent use of full-page spreads, especially in these moments of loss. When Gwija comes back to where her husband and son should be, for example, she uses three full pages with a silhouette of the husband and son as a recurring absence that will haunt the rest of her life. Just before that, the last time she sees her son, his face takes up the entire page, as if that memory takes up the whole of Gwija’s world. She also uses close-ups—often of faces, but not always—to express loss. When Gwija’s neighborhood friend tells the story of meeting her sister at a North-South Korea family reunion, Gendry-Kim focuses on their hands clasping, the friend outside the bus, with her sister inside, about to depart.

In the storyline set in the present, Jina struggles with how her mother seems to ignore her in favor of her brother. Jina was born after Gwija made it to what would become South Korea, while her brother is the son of the man Gwija marries, a man who also lost his wife during their escape to the south. Jina points out that her mother will never leave her neighborhood—Jina offers to have her mother come and live with her after she has moved away—because her son lives there. Gwija regularly buys her son new clothes, and, when Jina buys groceries for her mother, Gwija gives half to her son. Jina finally comments, in frustration, “Is she obsessed with Oppa [Korean word for older brother of a female] because she feels responsible for him? Or is she compensating for the son she lost? Does she feel sorry for my brother who’d grown up without his birth mother? Does she give him everything so that he’ll feel like he belongs, despite not being her flesh and blood? So that people wouldn’t look down on him? Or can it be that she hopes her long-lost son was accepted by a loving stepmother?” (233).

It’s this quote that encapsulates the tensions in this graphic novel. Jina, like many siblings, is trying to understand why her mother favors another child over her. No matter how logical that behavior is, it still strains the relationship between Gwija and Jina. Thus, on the one hand, this work explores the parent-child relationship that so many readers can identify with, regardless of our backgrounds. On the other hand, this work provides insight into an awful part of Korean history from a Korean point of view. Most Americans know little about the Korean War, and almost all of what we do know comes from an American point of view (see M*A*S*H, for reference). Gendry-Kim barely mentions the United States, as the focus is on the human cost of the war, as seen through one family’s experience.

Ultimately, what her work does is show the reader the devastation caused not only by the war, but by the continuing effects of that war and the divide between the two countries. Rather than trying to provide the grand sweep of such an important historical event, Gendry-Kim provides a close view of a woman who only wants to see her son again after spending most of her life without him. It is the human suffering, not the political ramifications, that she is interested in. She wants to show readers what that suffering looks and feels like, to remind readers of the individuals affected by decisions made by people who will never know them. And she succeeds.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply