This article is not a review of Kate Beaton’s Ducks. There are already many reviews of her autobiographical comic detailing her leaving Cape Breton to work for various fossil fuel companies in Alberta such that I don’t feel I’ve much to add in this regard. I agree with the general consensus that it is a masterful, empathetic, and observant work highly sensitive to the material realities of the oil sands. But I write because there is so much context missing from these reviews, particularly in terms of today’s growing media attention to Indigenous genocide and climate change. Instead of a review, I wish to share a personal response that begins with my giving a sincere thank you to Beaton for creating such an honest, human comic, for telling an important and highly regionalized working-class story, and for prompting me to reflect on my own time out west.

Like Beaton, I was figuring out what to do with my life after getting my undergraduate degree and I also decided I needed to move. In the late 2000s, I left Toronto to volunteer in various towns and hamlets in the Northwest Territories, all within the Beaufort Delta region and the traditional territories of both the Inuit and Athabascan peoples. All the communities I volunteered for were affected in some way by oil and gas prospecting. Volunteer is a critical word here. Unlike Beaton, my student debt was minimal and I did not have to contend with that albatross around my neck which was Beaton’s sole motivation for seeking work in the oil sands.

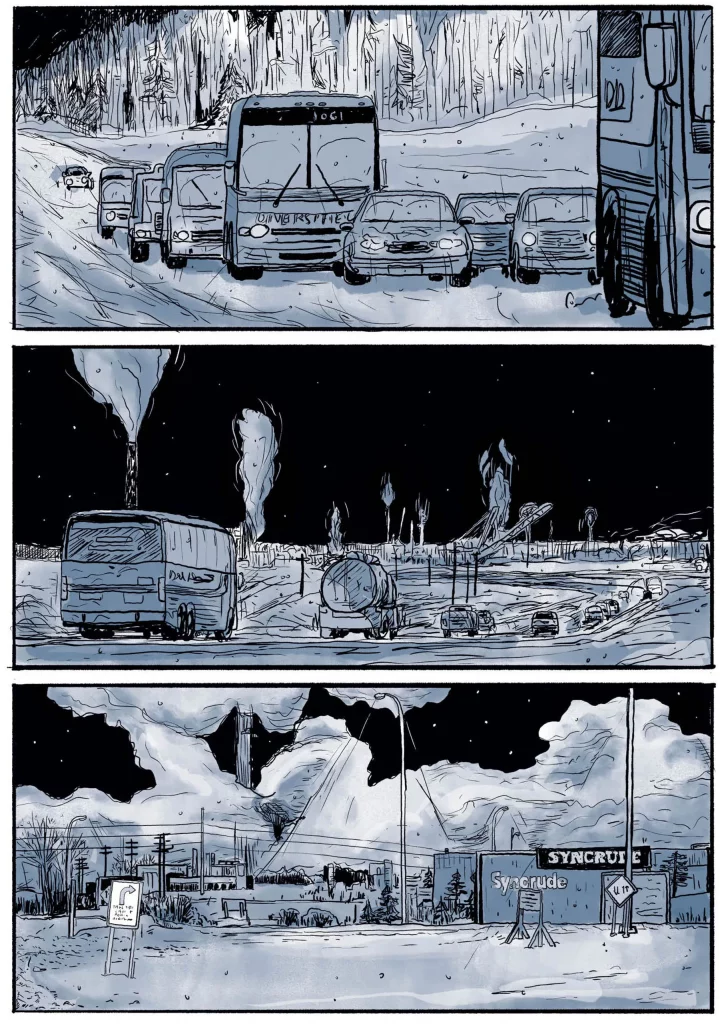

The first thing that strikes me about Ducks is how the environmental degradation of the oil sands is peripheral for much of the book even as this is included in many details beyond the titular vignette about the deaths of ducks in a tailing pond. There are the skin rashes workers must deal with, sarcastic comments about improved environmental operations, and the Edward Burtynsky-esque depictions of massive industrial sites. Yet the environment hardly factors into Beaton’s conversations with others. It is no accident that the human damage concentrated in Indigenous communities (but not limited to, as Ducks so clearly illustrates) and the environmental destruction of oil and gas are softened to the Canadian public. I also don’t think it’s an accident such subjects continue to be glossed over in Ducks’ reviews, many of which do not even mention climate change. This is literally a book about working in a fossil fuel industry; to omit climate strikes me as both completely absurd and entirely predictable.

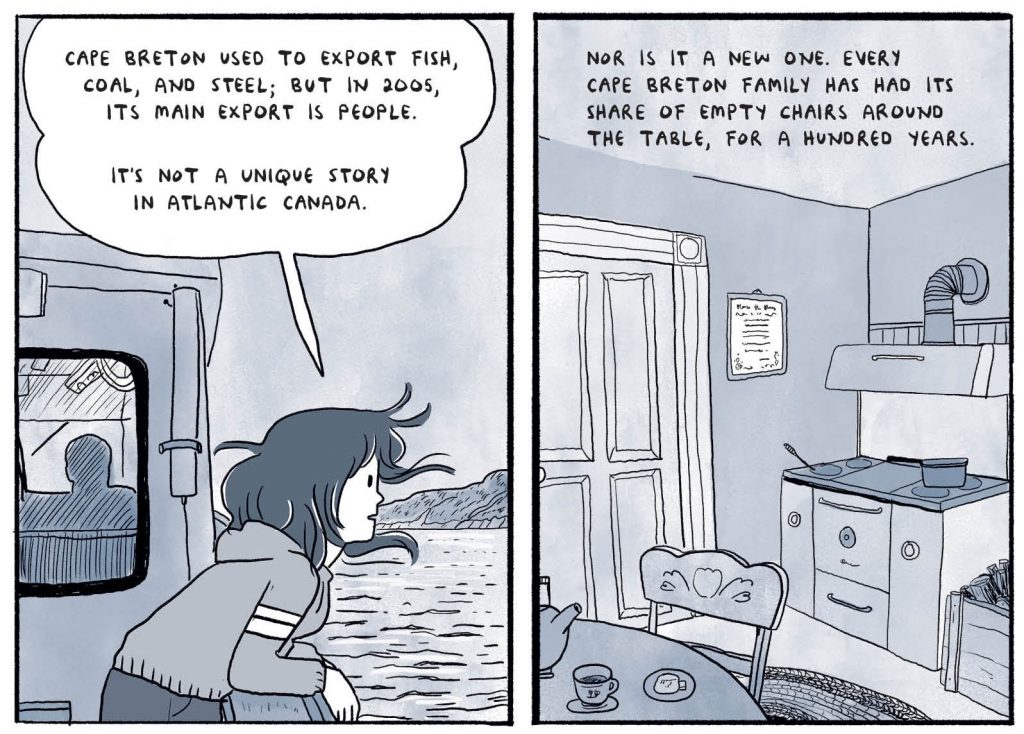

Readers may not be aware of Canada’s economic dependency on resource extraction and how the country’s prosperity is founded on a continual seizure of Indigenous land abetted by various programs of Indigenous disenfranchisement and genocide. The Canadian government has subjected Indigenous people to starvation policies, non-consensual sterilization, community displacement, residential school, forced adoptions of children, high rates of incarceration, and more. Canada is a country where its citizens today collectively pay the price to operate programs of disenfranchisement in order to benefit from extractive profits instead of making any serious investments into different (and potentially more sustainable) industries. Despite our highly educated populace and increased Indigenous representation in the media, I see little civic or activist organizing pushing to diversify our economy or engage in genuine reconciliation relative to other social concerns. I find Ducks, wherein bright young university graduates like Beaton end up finding their way to the oil sands to secure their financial futures, to be a vivid example of the consequences of this choice to stay the course.

Before I headed north, I was aware of the nature of Canada’s economy and how that impacted Indigenous communities, but for years, much of this awareness was gained entirely by accident. My knowledge about mining and Indigenous genocide came from reading books my friends might be reading, attending an event I caught wind of that was convenient to go to, or simply by virtue of having access to excellent library systems that allowed me to easily pursue research leads. Before the TRC Report, you had to be among certain people or be in certain places to even know what to look for. I’ll never forget the time I typed Barrick Gold into Facebook’s search only to see Spanish-language Groups rank as the top results, all highly critical of Barrick’s operations in South America. In this haphazard way, I learned that for certain nations, Canada was not the most friendly, inoffensive face of the G20 like I was raised to believe, but a hypocritical, rapacious country.

This is why I was not surprised when I learned how corporate “Indigenous Relations” operated on the ground in the north. From Indigenous corporate representatives entering schools to extol the promise of fossil fuels to only inviting supporters to a “community consultation”, nothing was too brazen. The only thing that was shocking to me was how little effort these companies made; they weren’t even trying to maintain the semblance of pretense. Instead, there was the pervasive sense that Indigenous communities were just stubborn scabs to be picked off in order to access the real value underneath – a mentality that northern Indigenous youth learned to internalize and that many adults, northerner and southerner alike, accepted as inevitable. Within this destructive framework, people made difficult trade-offs and decisions, forming a moral landscape as complex as any other.

Ducks is wonderfully human and relatable because Beaton wants to share the moral complexity of what it’s like being an oil worker. Where I lived, I saw similar tensions playing out with a highly transient southern workforce (including many hailing from the Maritimes like Beaton), and all the attendant negative impacts on people’s health and relationships. In addition to the southerners, local Indigenous people worked in and supported oil and gas as well, some of whom held far more political power than the white frontline workers featured in Ducks. And if you weren’t making oil money up north, you were certainly taking it; I could not disentangle myself from that, even as a volunteer. I depended on facilities built by oil money, participated in local programs funded by oil money – or to be more accurate, I was benefiting from profits invested into northern communities after being squeezed from oil workers like Beaton.

As such, despite being a Torontonian with a history of climate activism, I empathize with Beaton’s desire to present a more human portrait of the oil sands and the umbrage expressed at the way Canada’s Toronto-centric media landscape can demonize Albertan oil workers (and marginalize the Atlantic provinces). I feel this from both the perspective of an environmentalist and a rank-and-file union member. A Just Transition is easy to support when you don’t have to face the reality that the class of people profiting from the oil and gas industry have no incentive to transition their workers and the government is not much more motivated.

So yes, there is complexity. But it’s important to note there are also elements about fossil fuels that are dead fucking simple. In particular, it gets very simple for me when we consider the larger power dynamics at play, who is exercising that power, and the material effects this has on people, vulnerable communities, and our climate. I believe it’s a moral abdication to pretend otherwise. I am not suggesting that Beaton’s book is lacking because it’s not shoving these simple truths down the reader’s throat – Ducks is a memoir, not a polemic, and even then it seems clear to me that what I am raising here is present in Ducks in quiet, yet deliberate ways. However, the lack of serious engagement with these simple truths in so many pieces being published about Ducks, especially when considering their lack in the overall media landscape, just guts me.

We need not even consider what is peripheral to Ducks – Indigenous rights and climate change – to sense this lack of engagement. We only need to consider its central subject: labor. Labor is rarely interrogated in reviews, even though Ducks is first and foremost about work. There is a heavy sense of inevitability expressed by the workers in Ducks, as well as its reviewers: a sense there is no other choice than to find a job in the fossil fuel industry. To trade not only one’s work, but one’s physical health and safety, mental well-being, and personal relationships to make a decent wage. But just as Indigenous genocide is not inevitable, just as oil development is a choice, so too is the practice of the Atlantic provinces exporting labor. Who created and maintains these punitive economic conditions and how do they benefit from them? Who is working toward a different reality and how can they be supported?

I understand that reviewers are not obliged to explore larger analytical questions in order to tell readers whether a book is worth reading or not. It’s easier to stick to shorter, positive pieces full of deserved praise and autobiographical notes of interest, to continually allude to moral greyness, than it is to write articles that engage with Ducks’ disturbing material in more substantive ways. But I can’t help but wonder if these articles might have had a different tenor, might have had much more meat, might have drawn more connections between Beaton’s observations and larger systems of power, if they were written by Indigenous people or oil workers. Because while many Canadians dance around their discomfort around issues of race and class, Indigenous people continue to be oppressed and dispossessed, oil workers face being ruthlessly discarded whenever oil corporations pull out of Canada, and our oil industry continues to plunge us and the rest of the world into an ever-deepening path of climate devastation that lies not in the future but is plainly evident all around us now.

My personal response to Ducks would be to ask the reader to consider what you think the complex and simple truths about the Canadian economy, fossil fuel companies, genocide, and climate change are. To be aware of how complexity and simplicity are weaponized by those profiting from exploitation in order to distract and exhaust the exploited. To ask who is afforded complexity and who is made to be simplified.

One reason I chose to move to the north is because I knew all the stories I was seeing – misery children sniffing glue and decorative inukshuks trotted out for the Olympics – were a flattened southerner’s narrative. I had the great privilege of being welcomed into different northern homes and listening to what residents there trusted me with. And a lot of what they said cut through the obfuscating bullshit that muddies the harsh simplicities of their lives when it comes to capitalism, colonialism, and climate change.

One of my favorite memories of a late Gwich’in friend happened after we’d attended yet another one of these pro-oil community sessions. “No one ever talks about what will happen with the local economy after the decades or so of oil are finished,” I’d said before naively asking her, “I mean, that’s so short – what’s the plan?” She smirked, amused by the silly southerner. “There is no plan,” she replied, “All the oil will be gone, all the money will be gone, and maybe we can all go back to being Injuns again.” Ducks’ reviews show me that Canadians are genuinely open to the humanity of oil workers. This is critically important because we’re not going to get anywhere by refusing to recognize oil workers are regular people: people surviving in a capitalist world, people negatively impacted by punishing working environments, people capable of great care and great harm, people whose livelihoods will be seriously threatened by any large-scale transition away from oil and gas. I only wish that Canadians would be equally open to what is brutally simple as well.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply