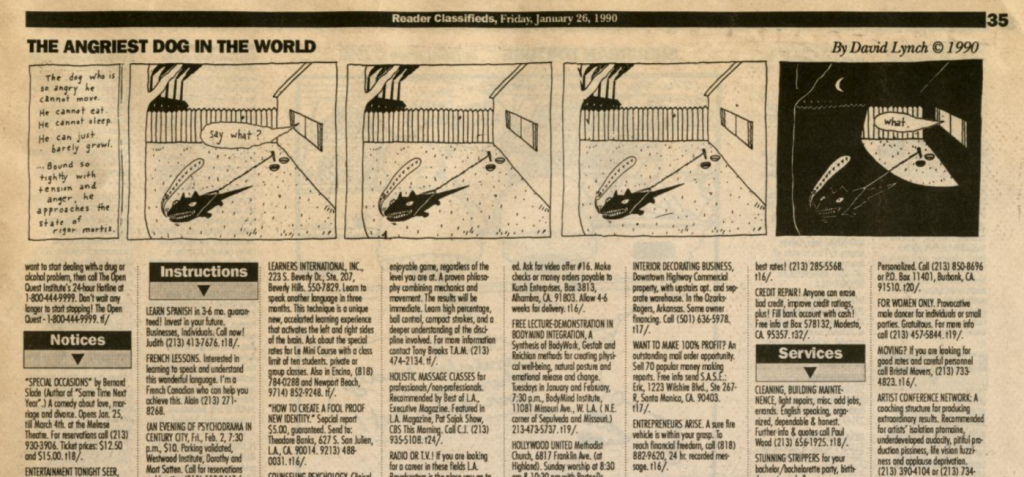

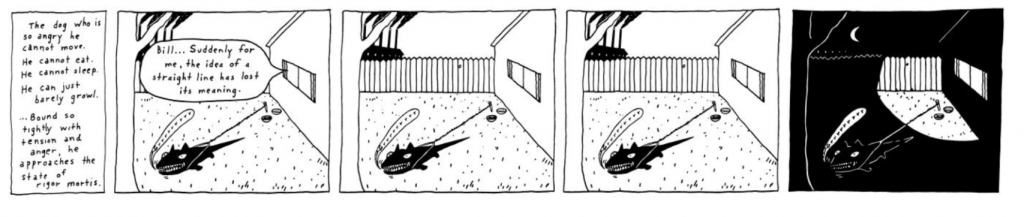

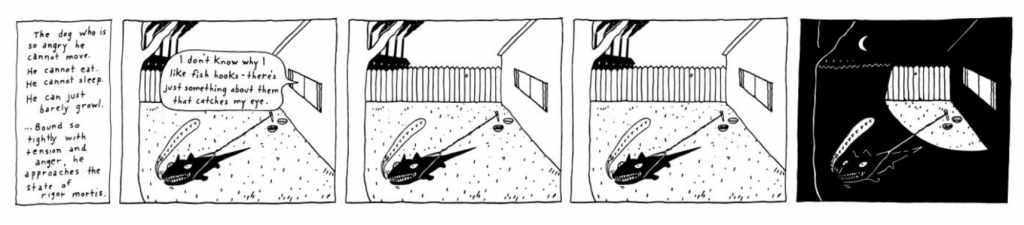

“The dog who is so angry he cannot move. He cannot eat. He cannot sleep. He can just barely growl. …Bound so tightly with tension and anger, he approaches the state of rigor mortis.”

This was the introduction to film director David Lynch’s comic strip, The Angriest Dog In The World, which ran between 1983 and 1992. It first appeared in the LA Reader and then in several other alt-weeklies across the country. This was during the golden age of alt-weekly comics that started the careers of Lynda Barry, Matt Groening, etc. Lynch was not nearly as prolific as those cartoonists, but the strip certainly served as a different way for him to investigate the same themes and techniques he explored in his films. In particular, Lynch’s merger of narrative, dream logic, investigations into the unconscious mind, and reminding the viewer/reader of the plastic qualities of the form were all present in the strip.

The art for the strip never varied. In its four panels, we saw a dog that’s so single-mindedly angry that he spent his entire day straining against his backyard leash and growling. The first three panels of each strip all took place during the day and the final one was at night, but night offered the dog no solace. The only thing that changed in each strip was the dialogue that emanated from the house. That dialogue ranged from dumb jokes to deep observations to absurd proclamations, and it was clear that it was this that drove the dog to rage. However, what the people inside the house said never had anything to do with the dog. That fundamental disconnect keyed the tension in the strip and recapitulated many of his themes as an artist, both present and in the future.

Lynch said in his book Catching The Big Fish: Meditation, Consciousness, And Creativity that he first sketched the dog while he was working on his first major film, the seminal underground body-horror classic Eraserhead. “I wondered why he was angry…and it struck me that it’s the environment that’s causing this anger…he hears things coming from the house.” One of the major themes of Eraserhead is the passivity of its lead character, Henry Spencer. This isn’t just passivity in the face of normal events, but rather in the face of an assault of his senses as well as multiple domineering presences in his life. He finally explodes underneath this pressure at the very end, committing a horrible act of violence. The dog in The Angriest Dog In The World is under a similar set of stressors, but he is reduced to a level of single-minded resistance that borders on self-harm.

In Eraserhead, Lynch used a barrage of sound and visual cues to create this nightmarish reality. In his strip, he used a simple technique of drawing everything at an extreme left angle (the eaves of the house, the angle of the branch, the smoke emanating from the nearby factory, and the dog’s leash) to indicate the pressure put on the dog, and then drew the dog pushing with all his might against these outside forces. The world was literally against him, and the dialogue emanating from the house was that last straw that drove it to pulling against his leash to that point of near self-strangulation.

There are other hints of future Lynch themes and tropes that he would explore in Blue Velvet and Twin Peaks. For example, the seemingly idyllic suburban environment seething with unseen, destructive forces is one of the central underpinnings of Blue Velvet. In the strip, that ominous factory belching smoke is never referenced by the text, but it’s certainly a crucial aspect of the setting. Especially since the people inside the house aren’t being directly exposed to its fumes, but the dog is.

Of course, The Angriest Dog In The World, at its heart, is a gag strip, although its humor often tended toward the absurd, the oblique, and the just plain random. Twin Peaks is full of this kind of surreal, unexplained humor, like the fish in the coffee pot in the pilot episode. It is a matter of interpretation of whether or not the text is directly commenting on anything in the strip; we are just getting a single, context-free snippet of a conversation or proclamation. For example, an early “punchline” was “People are dying living here.” It’s a perfect example of not just Lynchian randomness, but also Lynchian paradox.

On the other hand, “I don’t know why I like fish hooks – there’s just something about them that catches my eye.” could have been an actual thought by Lynch that he decided would be perfectly nonsensical. Then there are the occasional crude jokes, like “Bill, what is your theory of relativity? Life = shit^2” or “Did you know that Pinnochio loved birds? He did? Yes…he even had a woodpecker.” Even those gags that address the environment ignore the dog, like “Sometimes I look out over the yard at night and I get a peaceful feeling.” The best combination of Lynchian randomness and Lynchian Zen was “In gravitational fields, there are no such things as rigid bodies with Euclidean properties. That’s really, really, really damn good to know.” The overall effect is both delightful and bewildering.

The collection was published by Ryan Standfest’s Rotland Press, and his dedication to the details stand out here. It’’s published in a landscape format in order to mimic its original appearances in the L.A. Reader. Even the lettering was updated in a font that matches Lynch’s handwriting. This gestalt is not insignificant, because the replication of as many visual details as possible is critical to reading the strip. The most surprising thing about reading the collection is how fresh and funny each gag is, despite the unrelenting repetition of images. The tension that Lynch created in each strip, meant to appear at random in a newspaper, is an irreducible package.

As such, David Lynch may well have invented the meme. Memes not only recontextualize images with new text, but they are often presented in a clustered form on social media venues like Twitter. Of course, juxtaposing paradoxical, absurd, and contradictory images with text goes back to Dada, but the sheer rigidity and repetitiveness of Lynch’s strip was something new. That’s especially true because alt-weeklies at the time were one of the few ways of disseminating cutting-edge art to a relatively wide audience in the 1980s. A meme can just be a gag, it can be political, it can be philosophical, it can be shocking, and it can be random. It can be used by an artist to further explore their own ideas. Memes are flexible within their rigid visual structure because the text can change the meaning of the image. The Angriest Dog In The World is far from an anachronism or mere historical curiosity. It is a clever, studied roadmap to understanding how an entire younger generation processes and recontextualizes the torrent of information to which they are constantly exposed.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply