I have good news and bad news for you, dear reader. In my review of Spa by Erik Svetoft I wondered aloud if there is anything beyond our earthly experiences, if there is some greater purpose that transcends our flesh. Well, the good news is that, yes, there is more. The bad news, it would appear, is that it’s more of the very same. Decay collapsing into growth, entropy contorting itself into renewal, over and over forever. If spirit is in any way distinguishable from its housing flesh, it itself does not know the difference; it will, forever, be neatly folded into stasis, inconsequential little playthings that we are.

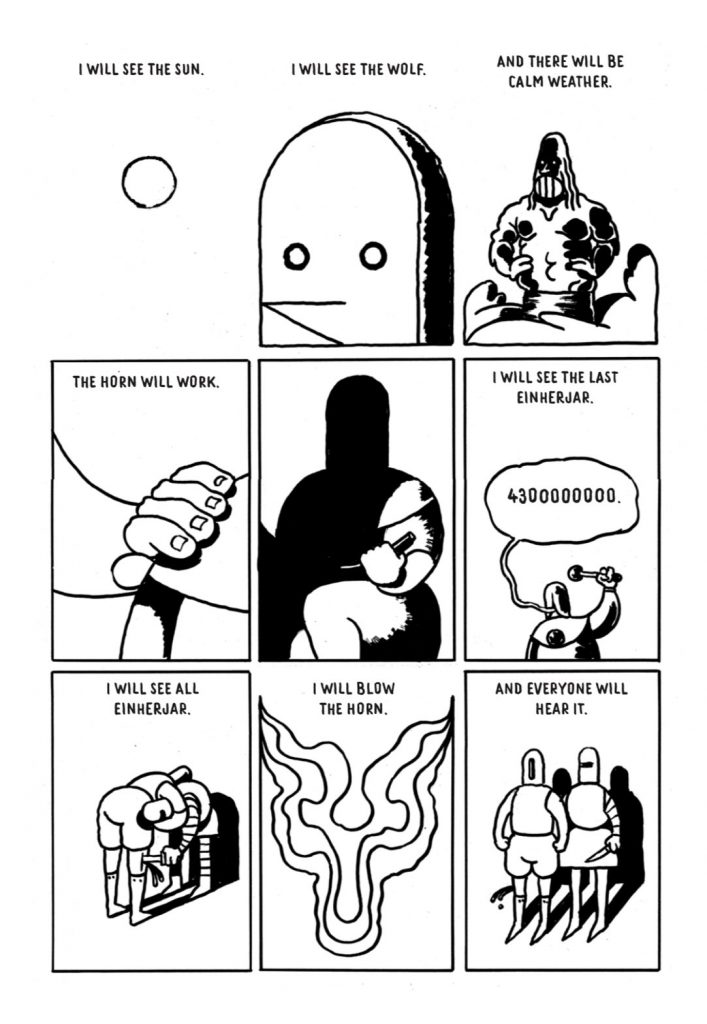

That is, at least, what Max Baitinger appears to suggest in Heimdall, originally published in Germany back in 2013 and newly translated into English in an edition published by Rotopol. Baitinger chooses Norse mythology’s watcher-protector as his point of view, as Heimdall breaks down the role he plays. Baitinger frames Heimdall as a figure whose tasks are laid out before him in almost obsessive detail: he is an observer more than anything else, witnessing heroic battle and tragic downfall, and even when his task is more active (blowing the horn to alert others of the onset of the end-times) it is because the circumstances have been vividly dictated. It is a prescriptive, narratorial affair, albeit one interested not in straightforward iconoclasm but certainly in a more profoundly existential malaise.

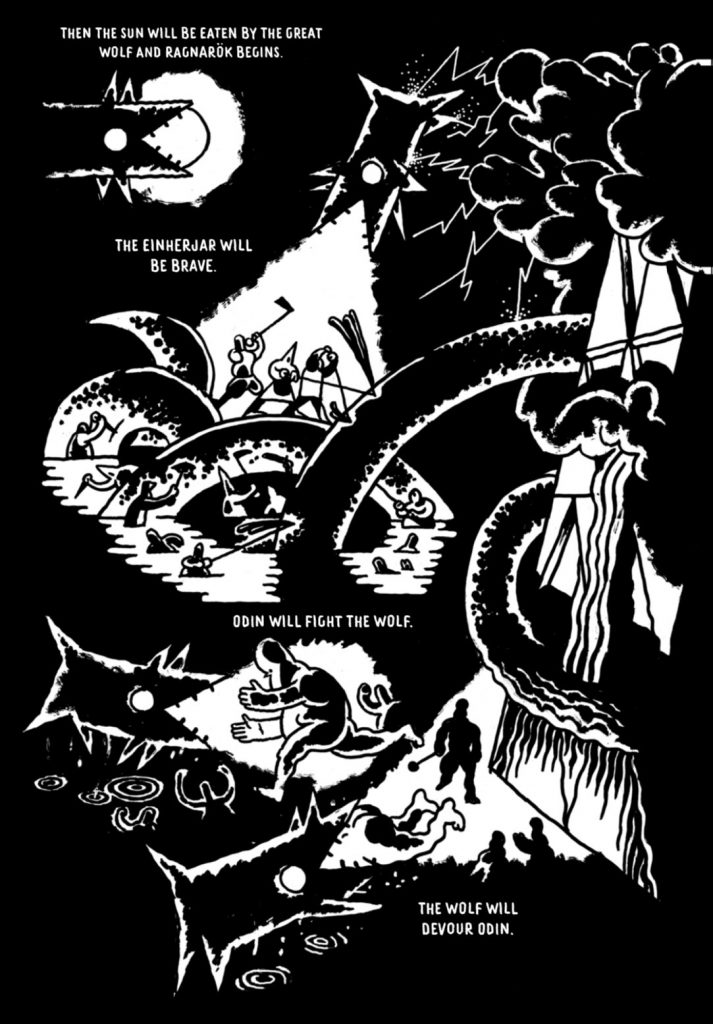

Heimdall is decidedly bored by the Wagnerian sheen of thunder and quake; its story is recited more than it is told, emerging as it does from the weariness of the predetermined, resulting in one of the most palpably frantic reads in recent memory: it manages a sincere, profound anxiety, coupled with a fear of its own conclusions, of its own futility. The oppressive rhythmics of Heimdall’s vision of eschaton, of himself pressed into it as a choiceless inducer, almost bring to mind Doctor Manhattan’s monologue in the fourth chapter of Watchmen: where Moore and Gibbons portray a temporal collapse by moving back and forth in Jon Osterman’s memories, oscillating between past and future to demonstrate his extra-chronological viewpoint, Baitinger achieves a similar effect through the exact opposite method, portraying an absolute linearity of events in such meticulous detail that it may as well be past. By the end, when the cycle of decay reaches its inevitable conclusion of rebirth, you are left to wonder whether, in a deterministic landscape, prediction and recollection are even distinguishable in any way worth remarking on, or if all events, future and past alike, are hollow in precisely the same ways.

Baitinger’s writing of myth is casual, almost conversational, in a fashion that recalls another 2013 release: Anders Nilsen’s approach to mythology in Rage of Poseidon. Baitinger, too, shares Nilsen’s interest in an emotion that transcends the aesthetically-human. The tendency of contemporary “reimagining” and “retelling” of mythological narrative appears to be to Make Them Like Us in more immediately-apparent, by giving the Gods smartphones or making them modern-day celebrities (or superheroes, for that matter), tending toward an attempt at circumstantial intermediation by pinning its narrative to the here-and-now; this approach certainly has its own place and is in no way invalid, but in its divergence it takes on a greater burden of demonstration as pertains to the necessity of its employment of mythology in the first place. But Baitinger, like Nilsen, plays a different dialectical game, choosing to keep the narrative intact while shifting the viewpoint by asking questions of emotional involvement—which pave the way into spiritual doubt.

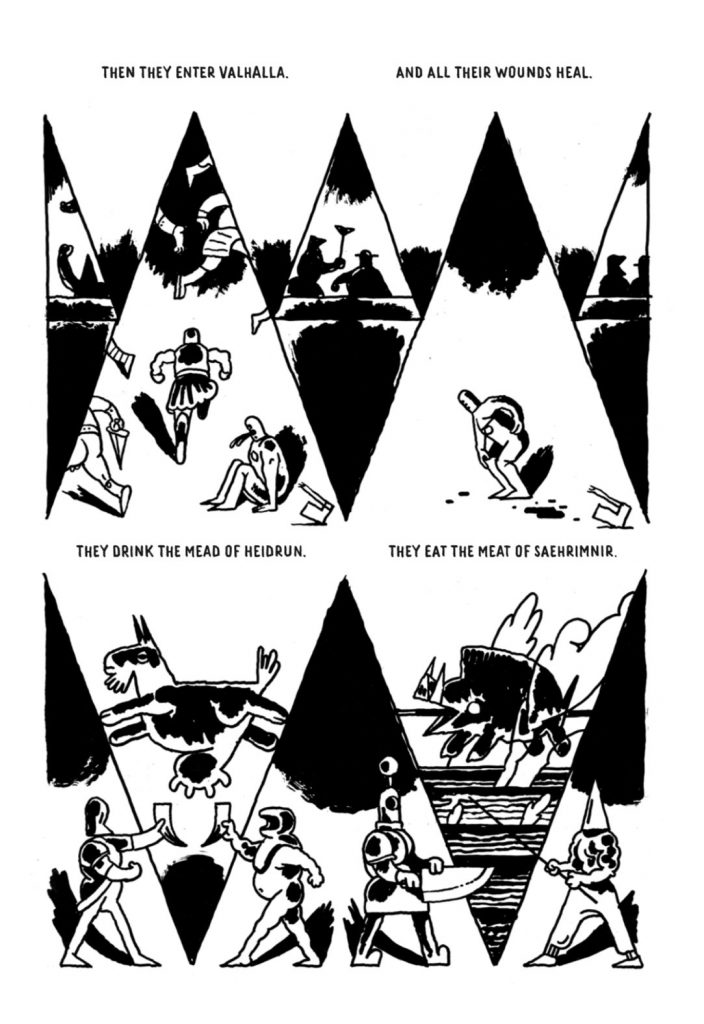

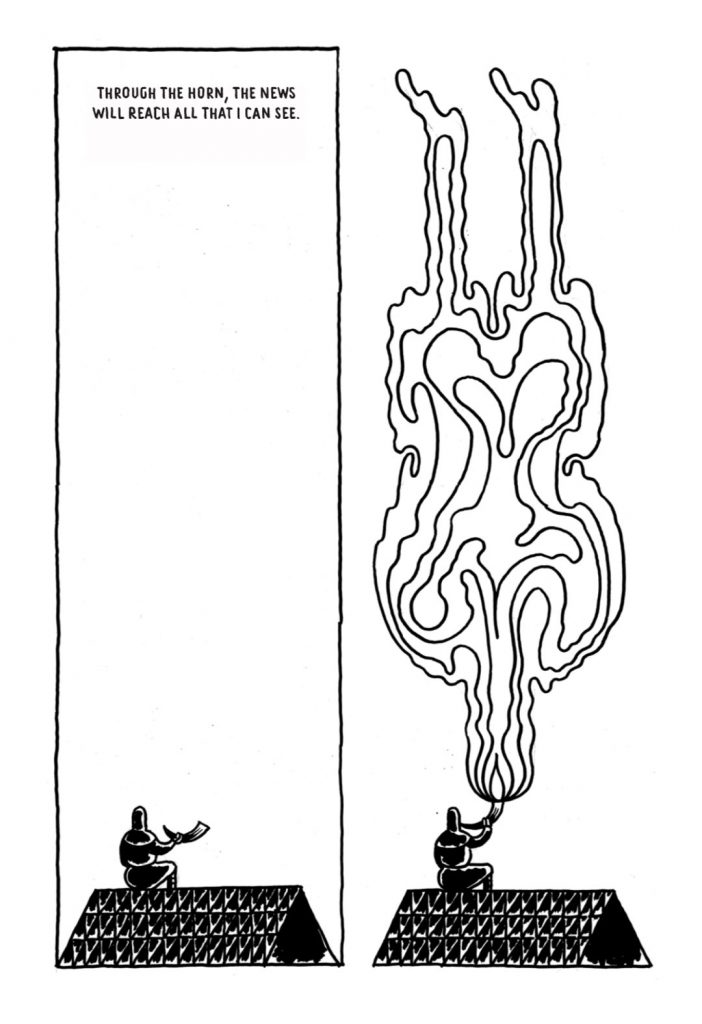

In his visuals, Baitinger speaks a language of cartoonish blankness as another form of distancing; it’s a wonderful contrast, underscoring the hollowness of the narrative, more habitual and incantatory than it is in any way propulsive. The underlying visual dialect is Tom Gauldian in its rigid simplicity, but, whereas Gauld opts for precise pen-work with fine rendering and sparing use of ink, Baitinger’s work is defined by thick, slightly tremulous lines of mono-textural ink, shying away from any particular angularities in favor of imprecisely rounded corners, laid out in strictly two-dimensional flattened landscapes; forms are more likely to be blotched with ink than they are to be rendered and articulated in detail, and characters are not detailed any more than is necessary to get their identity and general vibe across.

His pages, more often than not, are laid out in grids of equally-sized panels (his panels are often circular or triangular rather than triangular, breaking away somewhat from the predictable geometries of the fixed grid, but it is a purely cosmetic change, the panels functioning identically in spite of divergent shapes); even his breaking away from panel division altogether in his vision of Ragnarök, depicting its events as sequences that visually bleed into each other like a cave painting or a medieval tapestry, serves almost as a teleological suspension: that twilight of the gods washes over the reader for two pages of chaos, suspending the heretofore-planar, neatly-organized nature of narrative chronology—only to revert back to neat gridding immediately afterwards, chaos existing only to reaffirm the eventual, and really quite inevitable, prevalence of order.

By shifting the urgency of the narrative from external events of the epic to the internal monologues of its characters, Max Baitinger operates within the milieu of Norse mythology, but Heimdall‘s preoccupations appear more Ecclesiastical in nature; by framing Heimdall’s function as a spacetime panopticon he posits a determinism that is absolutely and irreconcilably at odds with the aesthetic sheen of the epic and divine. Richly and simply, agonizingly and beautifully, Baitinger does away with the imaginings of a happy Sisyphus and renders a profoundly sincere fear: that all of this—our Valhalla and our Heaven, our Odin and our God, our planting of Yggdrasil and our return to dust and ash—was all, with no exception or loophole, for nothing. And the worst part? Baitinger is such a strikingly strong craftsman, such a fine articulator of his case, that in my darker moments I am tempted to believe him.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply