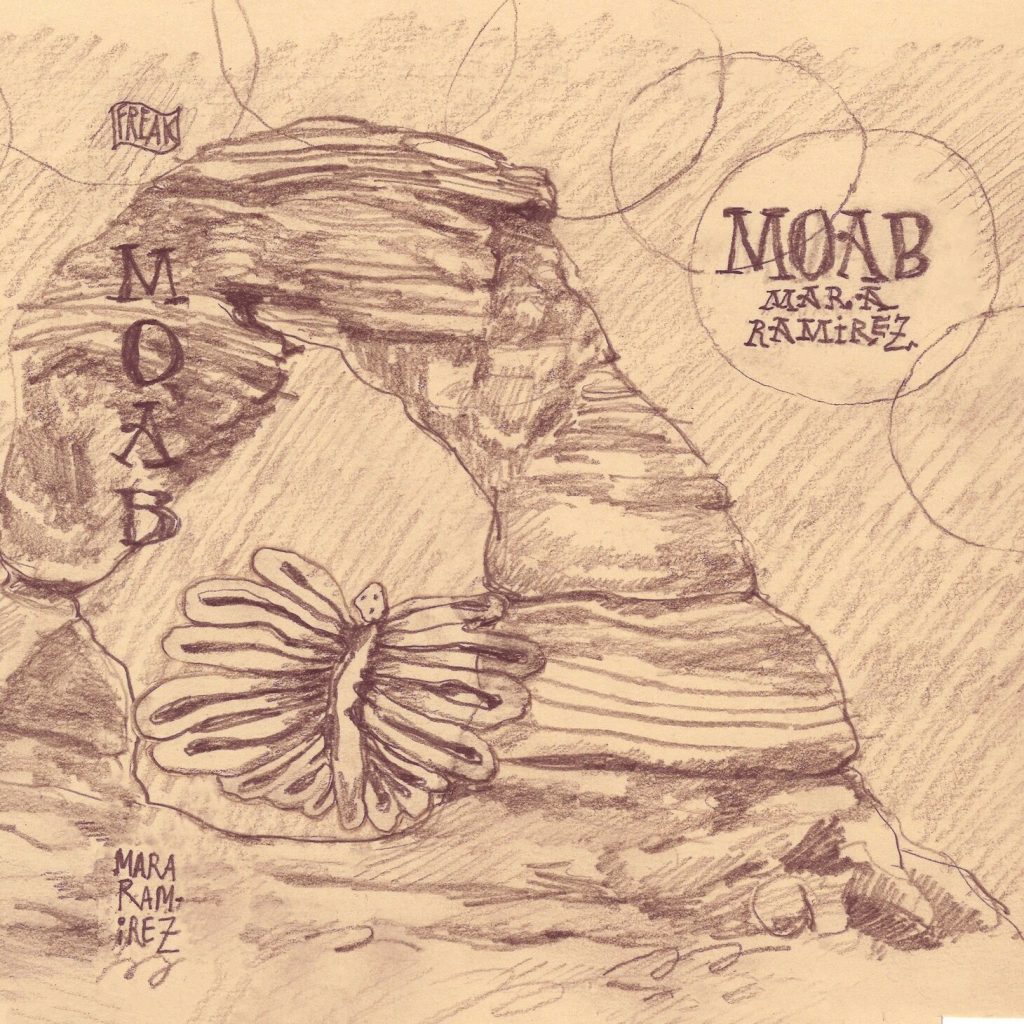

Philosophers, spiritualists, and psychologists have and always will argue and nitpick about the individual nuances that separate person from person, mind from mind, soul from soul. As much as the tranced-out hippie may try to tell you, we are not, at least literally speaking, all one. In this era of digital colonialism, these facts are intensely overbearing and omnipresent; the extreme ideological polarizations that vary from person to person seem to be incessant reminders, as unfortunate as it may be, that sometimes we can actually find solace in the fact that the human race doesn’t have to go on and attempt to get along all the time. It’s bleak, but it would be a fool’s errand to try and insist that division does not find ways to sow itself into any fracture between humans. And these fractures are not hard to find, especially in the tech-addled ideological battleground that is 21st century America. Strangely enough, though, it is for these reasons why the recent comic by Mara Ramirez, MOAB, is such a refreshing blast of fresh air, akin to rolling down a window on a long road trip; not only in the comics medium, but in the modern world as a whole.

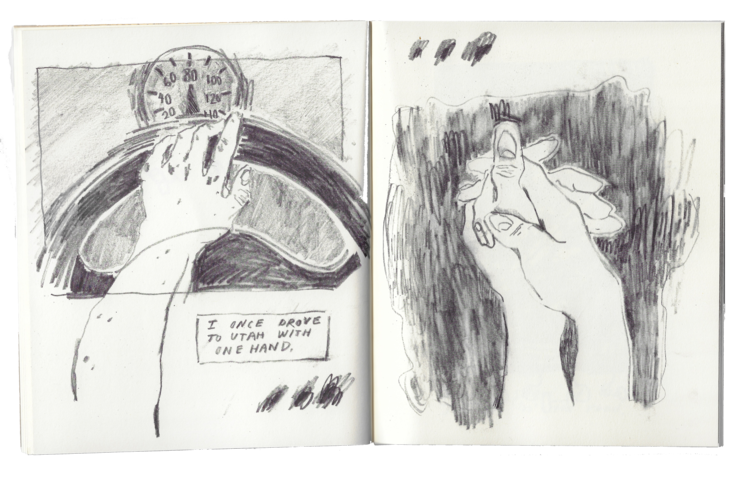

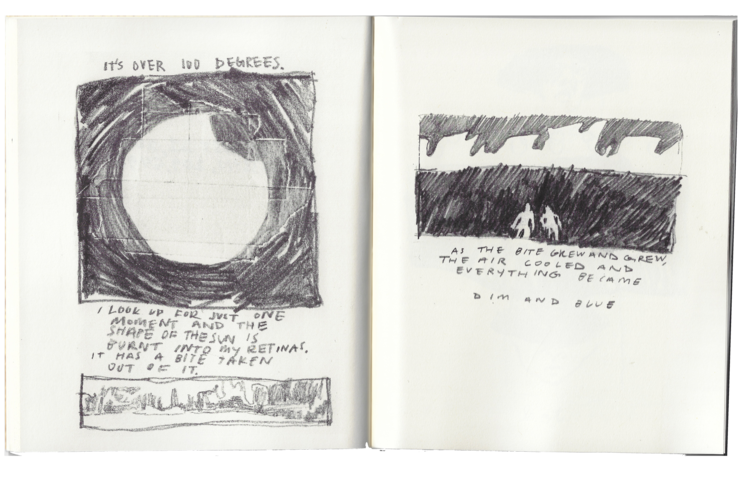

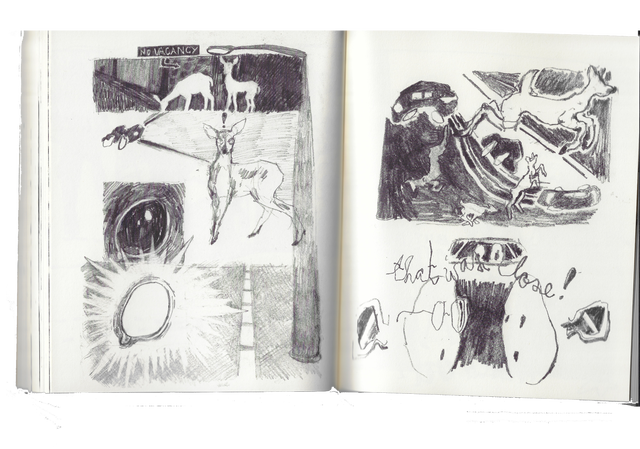

MOAB is a comic that stands sharply in contrast to many other contemporary alternative comics – specifically, comics that lay in the wake of forgotten goals, always imitating, but never truly subverting or creating. Although many critics may try to suggest that no art can truly stand alone from a school of influence, Ramirez’s work does in fact do this. Although Ramirez’s work can be compared to other cartoonists – Santoro, Frontera, or Madonna are some that come to my mind, I don’t think that Ramirez is trying to fit into any mold of what comics is, has been, should be, or will be, whatever that is. Comics culture has a tendency to be so overly analytical that we forget what it is that we all love – the pure and true act of simply creating. We may find ourselves lost in dogmatic systems of thought that subjugate creativity, truth, and beauty, however, when I read Mara’s work, I find myself lost in a world that remembers the infinite joy and thrill of being able to create something. These ideas are exemplified by the effortlessness of Ramirez’s drawings and writing – they seem to flow directly out of their brain, through their pencil, onto the page, and into our hands, allowing us to telepathically view and experience their daydreams, and hold on to those subtle and fleeting emotions that fly by us like summer days. In this sense, the experiences shared in MOAB are experiences that are extremely personal, but also extremely intrapersonal; using themes and experiences that stretch broadly over a wide range of human experience – namely, the crushing feeling of profound loneliness in a world that feels at times foreign, but also breathtakingly beautiful. This experience is so poetically rendered in Ramirez’s work – as the same feeling is generated both by the world within the work – the grand, towering and absurdly abstract sculptures of rock and the landscape that engulf it – and its characters, that exist in proportional juxtaposition to this external world, for these characters are experiencing a microcosm of mirrored experience. These characters are people that are supposedly close to each other, but under the microscope of MOAB, we see that they are actually very afraid- afraid of one another, afraid of themselves, and afraid of the world that they live in. Yet it is not purely fear that drives these characters, as they, like us, are complicated, sensitive, and imbalanced arrangements of motion and emotion. They are such temporal beings, not even remotely superhuman, as they stumble over things, physically and emotionally, in a landscape that is at once natural, supernatural, preternatural, and unnatural, that is, in a sense, our modern world.

An idea that resonates with me when reading MOAB is the concept of the “sublime.” According to the philosopher Edmund Burke, the sublime refers to a feeling that is not the appreciation of beauty, but more so the amalgamated feeling of fear and awe at something that is more than beautiful, something so immense that it has the power to shake one’s entire being to their core. In Burke’s own words, the sublime is a sort of “tranquility tinged with terror.” The sublime is often associated with means of experiencing landscapes. For example, standing on the top of the Swiss alps and staring out at the frost-covered mountains for miles would likely induce the transcendental feeling that is the sublime. Decades later, the philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer famously expounds on this concept of the sublime, with Schopenhauer separating the sublime into two separate camps: the dynamical sublime and the mathematical sublime. The dynamical sublime refers to a physical sublime, whereas the mathematical refers to a psychological sublime. Schopenhauer also begets a more distinct and exact clarification between what is simply beautiful versus what can be defined as truly sublime, distinguishing the beautiful as being simple pleasure, and the sublime as being mixed with pain.

This is part of what elevates MOAB to a truly grander plane. For centuries it has been the goal of artists worldwide to be able to capture the feeling of the sublime succinctly. Ramirez’s work does more than this. MOAB plunges the reader headfirst into a world of philosophical and psychological uncertainties, where Ramirez’s own experiences are used to raise the reader’s to a higher level, but not a level that is devoid and safe from analysis, instead, one that is more subject to it. MOAB also effervescently fuses the dynamical and the mathematical sublime together, like a complex strand of DNA, while we see the characters toss and turn as they wander along in a landscape that is too, tossing and turning. And MOAB truly succeeds in this, and, in this sense, it is what can be called a truly transformative work and transgressive work. This is a work that is deceptively simple in how it guides the reader, but in the end, leaves the reader somewhat shaken by the sublimation of the experience that they undertook. MOAB is a brief read, and gentle too, so it takes time after reading for the gravity of feeling that Ramirez grapples with to sink in. This leads the reader to question their own experiences, digging into their memory bank for other journeys that are equal parts profound and mundane, creating a connection between two acknowledgments of the sublime. It is these experiences, the profound and the mundane that we all inexplicably are filled to the brim with, and truth be told, we don’t know what to do with the accrued collection of them over time. But MOAB reminds us that to be human is to accrue these experiences, and it is life-affirming. MOAB is a work that once fully read and experienced will change you, and change your perception of the world and of comics as a whole. This is a work that has the potential to raise the mundane to the sublime, which is no simple task. In the past, the idea of the sublime was rendered as needing to view or experience something that was earth shaking, like standing at the top of the Swiss Alps. Here, rather, the sublime is quietly shown as being those moments we don’t know what to do with – that soak us up like a sponge – while Ramirez celebrates this act in the truest and most natural form they know. To me, this is what subversitivity in comics looks like – not the redundant rejection of “politeness,” “political correctness,” or “social norms,” but the rejection of antiquated methods of perceiving the nature of life itself. In this sense, MOAB is a work of art that is, truly, sublime.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply