Yuval Noah Harari is one of the most popular historians of the 21st century – he is a regular guest of political and cultural programs, an experienced TED speaker, and has his own YouTube channel. Now, with the adaptation of Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind, he is entering the stage of comics. Sapiens: A Graphic History is a creative and witty adaptation, scriptwriter David Vandermeulen and artist Daniel Casanave bravely evoke genres such as the superhero tradition, the reality TV show, or courtroom drama.

Our Species

Harari has a doctoral degree from the University of Oxford, and it is fair to say that his earlier monographs on military history were read by a smaller number of people than Sapiens, published in English in 2014, which has been recommended by Barack Obama, Bill Gates, and Mark Zuckerberg as a book worth reading. Harari’s further books, Homo Deus and 21 Lessons for the 21st Century continue to connect the history of humanity and the challenges of the present. Harari reveals a complex view of human history inspired by contemporary biology, archeology, and sociology. History, which in this view is more than the study of written records, reaches back into what is traditionally known as prehistoric times and helps us understand the place of humanity on planet Earth. Our species, the homo sapiens, is seen in a global system, where the world “global” here does not refer to the world wide web or global trade – instead, it refers to the notion that our species is and has been connected to the Globe, to its ecosystem and to the history of its ecosystem.

In the age of climate change and the sixth wave of extinction, both accelerated by our species, we need to consider homo sapiens as part of the biosphere and to think of our existence in a biological sense, as a species. Thinking in terms of the anthropocene is not new. Harari, then, is not a lone fighter. Still, his sometimes provocative arguments, conversational style, unique associations, clear reasoning, and his examples taken from all walks of life contribute to the fact that his books have been translated into 60 languages and have sold 27,5 million copies.

Comics and Science Communication

Though the term “science communication” seems to be exclusively associated with the hard sciences, I believe that we can and should talk about science communication within the Humanities. Harari repeats in each interview he has recently given that people of science need to be able to explain their results in vernacular terms, as distributing knowledge is the way to prevent conspiracy theories and pseudoscience. If we consider the discourse around COVID-19, masks, and vaccines, we see that in many countries scientific discourse is intermingled with political discourse and that certain scientific statements and claims are ignored or denied by groups of people. Even within this context, Harari reminds us that more people trust science today than at any time before. For example, several churches have taken heed of warnings coming from scientists and held (or still hold) their services in empty buildings with online access.

Being up to date about scientific issues can help our societies get ready for the challenges of the 21st century and respond to the challenges of AI, bioengineering, and climate change. The comics version of Sapiens was conceived as a result of this need to communicate and educate societies.

Adapt and Expand

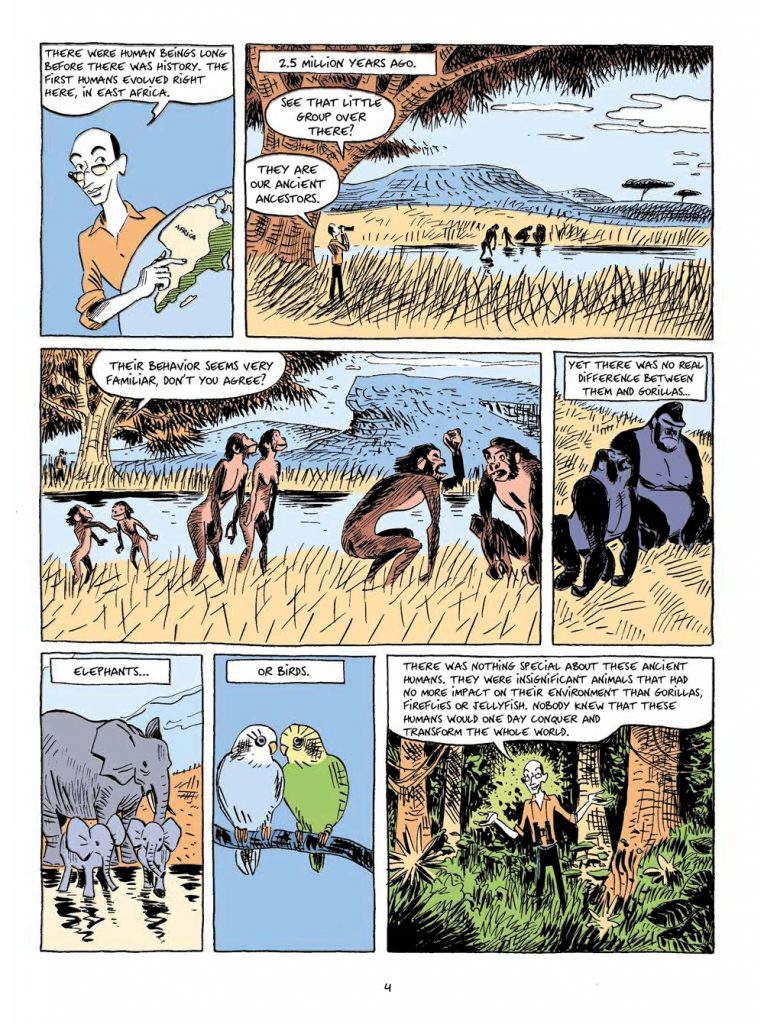

Sapiens: A Graphic History reimagines the first of the four parts in Harari’s original book. Part one, “The Cognitive Revolution” is roughly 80 pages long – it is reinvented as a 245-page book format comic – or graphic novel, if you will. Vandermeulen and Casanave work under ideal and rare conditions: instead of spending weeks on how to reduce the original and being judges of what to cut in their adaptation, they were given the opportunity to expand Harari’s text. With their creative methods, they create new environments for the original text which now exists within the context of images and sequences, becomes part of the page design, and is enlivened by (visual) jokes that return within the whole volume. The sentences of Sapiens the prose work are inserted into situations, they are inserted into various genres, and they have been reinvented as comics.

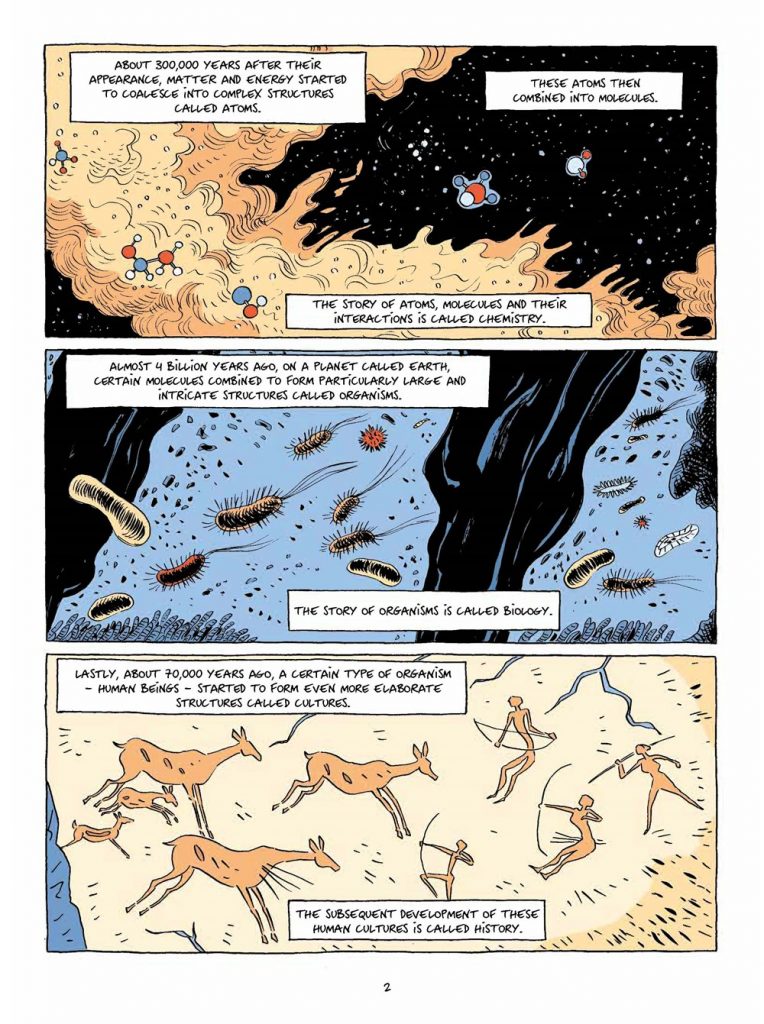

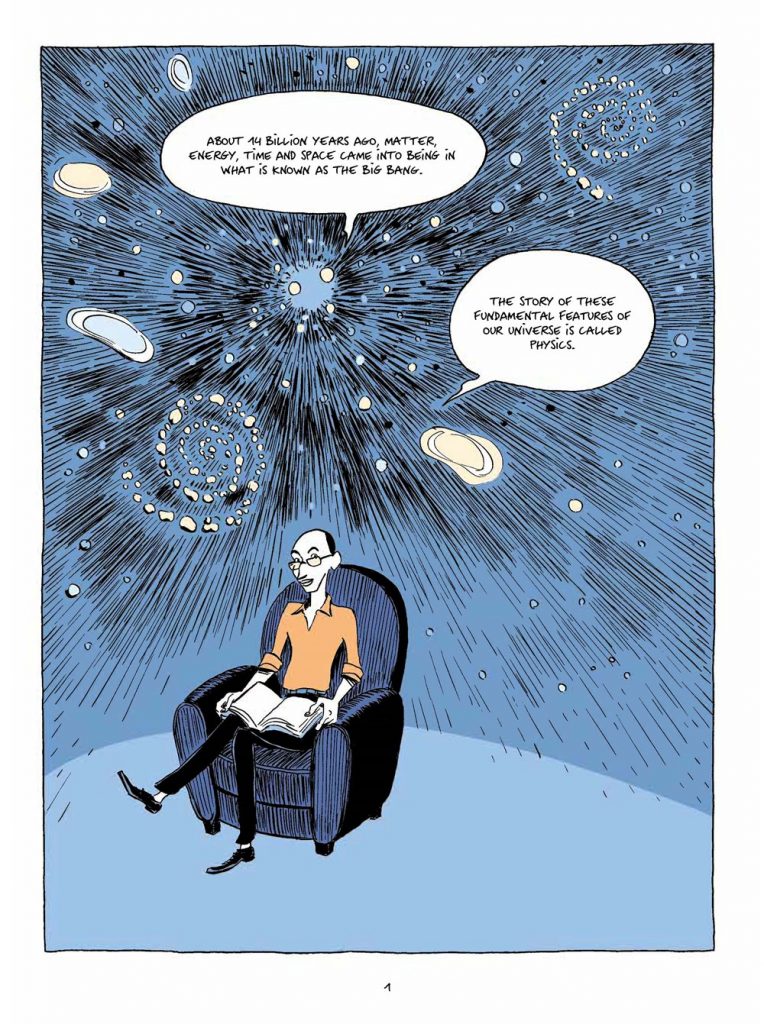

Harari is shown as a character within his own work as early as on the first page: he is sitting in a comfortable armchair with the universe behind his back. To avoid confusion, I will refer to the character as Yuval, and to the actual historian as Harari. Yuval is entertaining the reader with stories. This, however, is the most predictable trick of Vandermeulen and Casanave’s adaptation. Nothing is easier than adapting a piece of scientific writing than adding some speech balloons and turning the author into a talking head. Vandermeulen and Casanave do a lot more, though, in their drawings and designs they make biological and historical processes come alive.

To represent scientific arguments, the adapters turn to visual associations and artistic rephrasing as well as to introduce new characters. They introduce a sidekick to Yuval, Zoe: the questions of the always curious niece echo those of the reader’s and contribute greatly to the way the arguments are elaborated.

The adaptation features several fictitious researchers: they are anthropologists, biologists, researchers of communication, which emphasizes the interdisciplinary nature of Harari’s thought. The arguments are framed here as parts of lectures at universities, TV interviews, roundtable discussions, or as informal discussions shared with a glass of wine in hand. By inserting scientific thinking and reasoning into specific situations and by showing experts who disagree, the graphic novel highlights that science is done by sharing and discussing results and positions as well as by building on earlier results of other people. Because of this, scientific discourse is as much a protagonist of Sapiens: A Graphic History as the character based on Harari.

To illustrate how the visual creativity of the graphic novel supports the text that it adapts, I would point to one of my favorite panels. This panel frames current scientific theories in the context of their history and it is a most trivial moment: Harari’s character and Zoe are going to listen to a (fictional) friend of Yuval, Prof. Saraswati, an erudite professor of biology. In the lecture, Prof. Saraswati will elaborate on the concept of “species” for the benefit of Zoe and the reader. In this particular panel, however, she is not present and they are not in the lecture hall yet, they are simply passing between two significant locations. Yet, in the background of the panel, we can see statues of significant researchers working on taxonomy and categorizing life forms such as Linné, Lamarch, Cuvier, and Darwin. By adding the busts, Vandermeulen and Casanave add visual details to Harari’s text and create new correlations.

Visual Storytelling

Jonathan Gottschall called the human species the storytelling animal in the title of his 2012 book. Harari also emphasizes the role of tales, myth, gossip, and stories in the history of our species: the ability to tell stories is as important as taming and using fire. In fact, Harari argues that homo sapiens spread and became a dominant human species 50.000 years ago because of its unique language and unique way to tell stories that are not directly related to the present. Harary uses the word fiction for stories that are not limited by the here and now and that allow for abstraction. In contrast to, say, the homo erectus, homo sapiens could and still can invent, believe in, and share fiction. Possibly the most provocative idea in Sapiens is that Harari uses the word “fiction” for religion and human rights. Both are, he argues, invented and shared by people. Fiction, then, is a powerful force that can unite a community. Shared fiction can align the dreams and deeds of people who do not know each other and shared fiction – that is, shared stories – make cooperation, including trade and religion, possible.

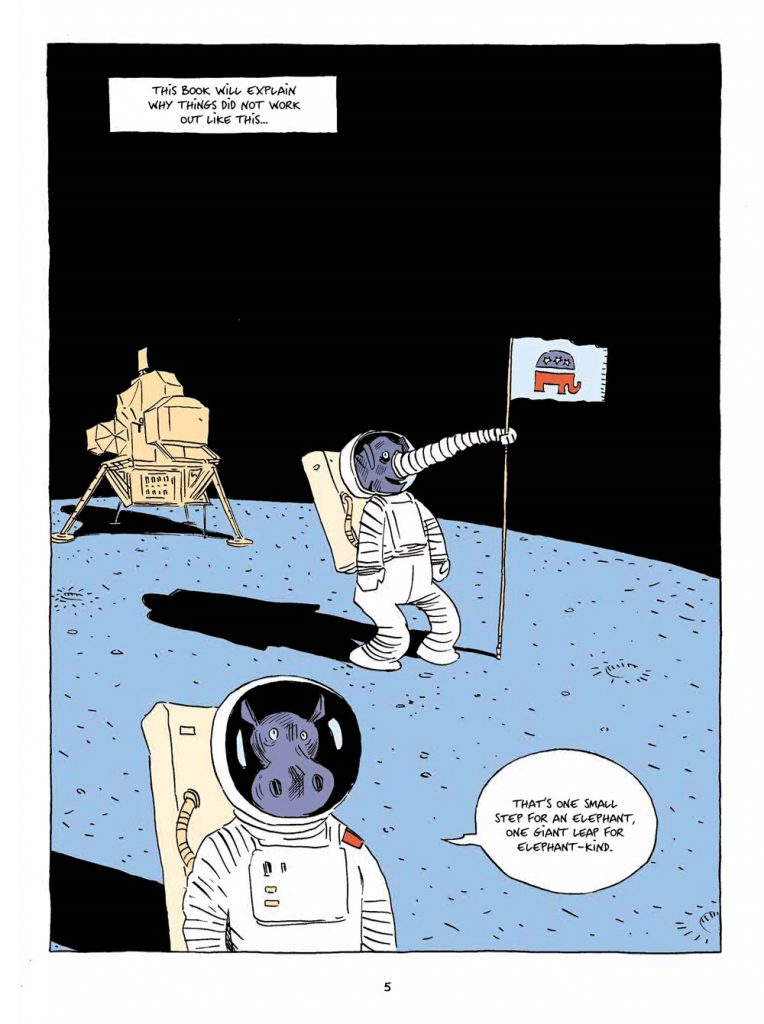

When adapting the above to comics, there is a danger that it turns out as a dry, text-heavy argument. The adapters reach out to the superhero tradition to enliven this section: they invent Doctor Fiction, who becomes the literal embodiment of the study of stories – and, with a tongue-in-cheek self-reflective gesture, Doctor Fiction is a fiction shared by the readers of the graphic adaptation. She defies all gender-related stereotypes with her outfit and looks – again, within the superhero genre that has a history of being stereotypical about the representation of male and female bodies. Another genre that the adaptation successfully incorporates is reality TV: the already mentioned rivalry between various human species (Homo neanderthalensis, Homo erectus, Homo luzonensis, Homo denisovensis, Homo sapiens and Homo floresiensis) is framed as the show Evolution that can have only one winner (spoiler: it is Homo sapiens).

I particularly enjoyed the self-reflective gesture of playfully incorporating a comic within this comics adaptation. In the short episodes, we follow the lives of Prehistoric Cindy and Prehistoric Bill, two of our ancestors. These comics reflect an earlier Franco-Belgian comics aesthetics in their linework and coloring. Visual versatility is one of the great pleasures of reading the adaptation, visual easter eggs reflect on the history of visual culture as well as on the history of (particularly Franco-Belgian) bandes dessinées.

The most exciting part of the adaptation to me is the last section, which builds on detective fiction and courtroom drama. Here, Detective Lopez, the shrewd New York cop is investigating a serious crime against animality: the extinction of giant mammals. She suspects homo sapiens to be responsible: the current ecological crisis is not the first time our species has radically altered the ecosystem. Lopez takes the suspects – Prehistoric Cindy and Bill, who this way exit the world of the comic within the comic – to court. Lopez needs to convince Adamsky, the tough lawyer representing the Prehistoric couple, but her arguments offer the reader new ways to think about the history of their species. This quick-paced section is a spectacular visualization of the drama that is inherent both in Harari’s prose and in the history of our species.

The successful incorporation of the listed genres – and many more – is proof that homo sapiens is indeed a storytelling animal and we are still fond of stories. Harari’s materialistic approach does not map the spiritual needs or journey of our species – instead, it provides insight into how these early societies might have been organized with the help of shared ideas and shared stories. Though the societies of the stone age perished without any written record about their social structures and most of their objects were made of wood – and not stone! – we can theorize about them by relying on anthropology and zoology, and the graphic adaptation does an excellent job in retracing the arguments these sciences allow for and also showing their limits (talking about zoology, here is an interesting The Infinite Monkey Cage podcast episode on chimpanzee societies, which are just as nuanced as ours). Reading Sapiens made me think differently, not simply about the cultural history of humanity, but about the natural history of my species. One of the greatest merits of Sapiens is definitely calling attention to the role of storytelling in modern-day science, contemporary entertainment, and in organizing the first homo sapiens societies 70,000 years ago.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply