American citizens have a responsibility to remember Guantánamo. Admittedly, this is a strange injunction. How does one “remember” a crime still in progress? The prison, opened four months after 9/11, was never closed. It holds 40 men, many of them “forever prisoners” who face no charges but can’t leave. The prison is preparing for some to die of old age (though a second Democratic President has signaled his intent to close it).

And yet, Guantánamo feels past. Perhaps, as with America’s War on Terror, longevity is the culprit. The longer the prison persists, the harder it is to see clearly. This peculiar condition of perceptual slippage is what journalist Omar El Akkad calls “the most insidious aspect of Guantánamo Bay’s legacy.”

“Even though the camps still house prisoners, the entire place feels like something from a prior epoch, a piece of ancient history,” he writes in the introduction to Guantanamo Voices: True Accounts from the World’s Most Infamous Prison (2020).

These true accounts are, according to El Akkad, “an antidote to forgetting.” They also contribute to the collective effort of building a civilized society. Learning the history of Guantánamo will (the implication is) help Americans confront their base instincts of “communal hatred, fear, and cowardice.” Otherwise, El Akkad writes, these instincts “will resurface and give rise to new nightmares.”

Arresting the slow erasure of Guantánamo from America’s consciousness is a noble, necessary project. And Guantanamo Voices, a comics oral history, is a well-crafted tool of collective remembrance. But before Americans can fix anything, they must understand the problem. A close reading of the book reveals how excruciatingly difficult this is. In telling the stories of people who suffered Guantánamo’s brutality and resisted its secrecy, the comic also traces the enormous barriers that impede our understanding — and our ability to reckon with its legacy.

Guantanamo Voices was edited by graphic journalist Sarah Mirk and illustrated by a range of talented cartoonists. The comic follows ten people, including Mirk herself, as their lives intersect with the prison at Guantánamo Bay, Cuba (also known as GITMO). Mirk, an editor at The Nib and a digital producer for the investigative news outlet Reveal, describes the book’s origins in the opening chapter. Her interest began in 2008 after a “chance encounter” with a Guantánamo veteran. The two became friends, and Mirk, an unpaid newspaper intern at the time, was curious about the veteran’s experience of the prison. She started asking questions, interviewing prisoners, and talking to other veterans. She finally visited the prison in 2019, and her trip serves as a frame narrative for the book.

While the first and last chapters are told from Mirk’s perspective, the comic is primarily a work of journalism and history, not memoir. Mirk’s reporting provides the narrative backbone for the central chapters, each of which follows a different character. Mirk interviewed her subjects: prisoners, veterans, and lawyers (a lot of lawyers). She consulted news articles, public documents, and other published sources. The comic was fact-checked by independent journalist Andy Worthington, author of The Guantánamo Files.

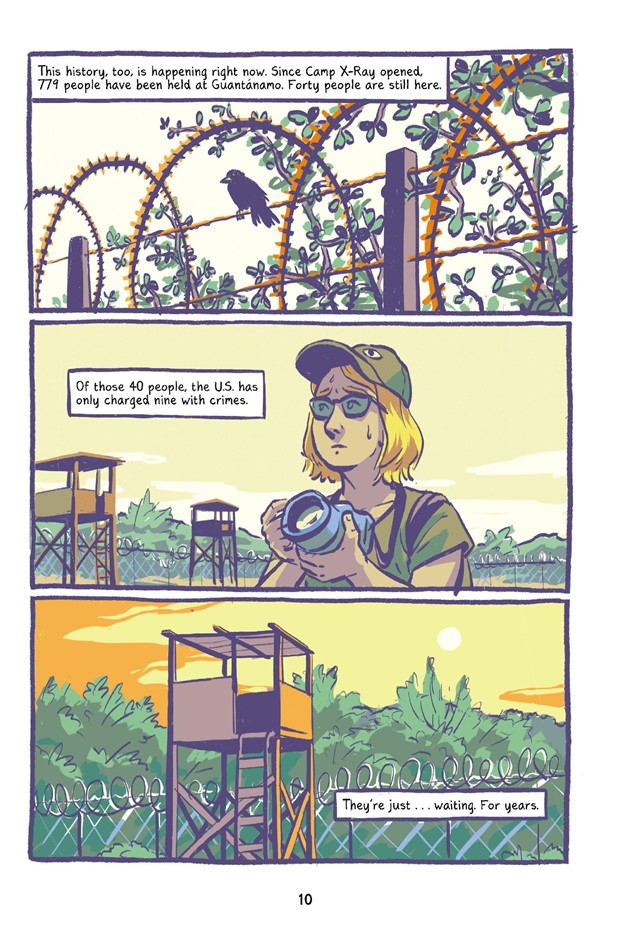

To orient her readers, Mirk provides colorful, hand-drawn infographics and an illustrated timeline at the front of the book. The facts she presents there are stark: Over 90 percent of the nearly 780 prisoners who have passed through the prison were released to other countries. Nine died in prison. A bare handful have been charged or convinced since 2002. As the book shifts from data to narrative, it keeps its eye on the larger contexts that shape each story. Mirk often weaves in brief accounts of major political developments, such as President Barack Obama’s failed attempt to shut GITMO. We are reminded in chapter nine that overwhelming, bipartisan opposition from Congress kept Obama from closing it or bringing prisoners to American soil.

Still, Guantanamo Voices does not attempt to write a definitive history of the prison, nor does it offer a full accounting of its political consequences. It is an attempt to make the prison comprehensible on a human-scale. The individual narratives are deeply personal, often depicting scenes from characters’ childhoods. We learn that former prisoner Moazzam Begg, who spent nearly two years at GITMO, grew up in Birmingham, England, where he attended a Jewish public school and took after-school lessons on the Quran.

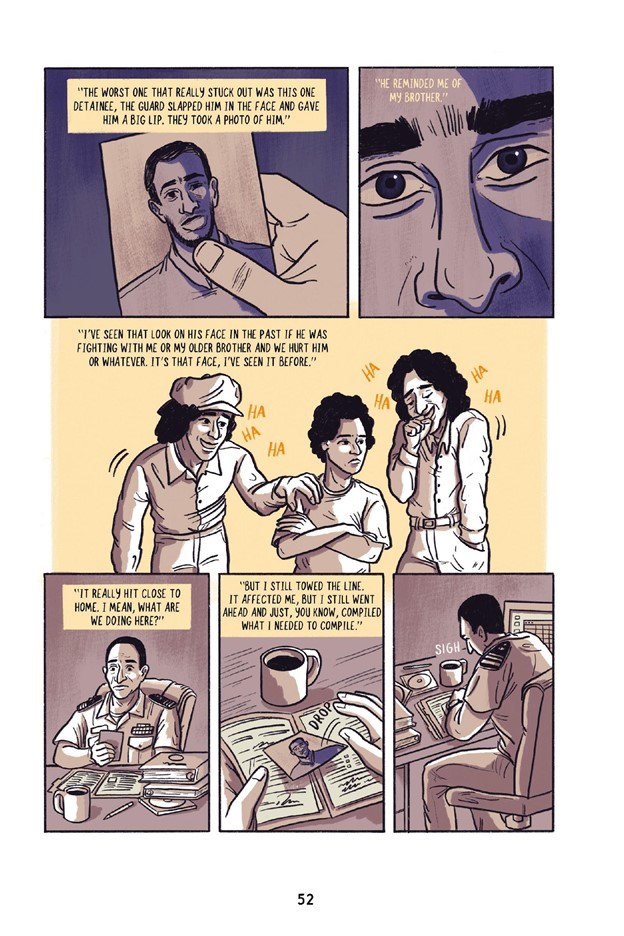

Other personal details are more disturbing, such as the images of Begg’s physical abuse. The narrative shows him being kidnapped at gunpoint and, a few pages later, how he and other prisoners were stripped naked and photographed. One panel depicts them kneeling in a line, all wearing black hoods reminiscent of Abu Ghraib. Another panel shows an unnamed man pulling on gloves as he announces “Cavity search!” After Begg is transferred to Guantánamo, the humiliations become more subtle and more absurd. He is given letters from his family, but one penned by his child — its border decorated with cartoon fish — is heavily censored. Released to England in 2005, Begg was one of the many prisoners never charged with a crime.

Omar Khouri, the cofounder of the Beirut-based Samandal Comics, illustrated Begg’s story, and he depicts scenes of horrific abuse and confinement in dark, thick lines. Khouri’s backgrounds and faces are crowded with marks that aren’t strictly “necessary” but which give ominous weight to his pages. Khouri is one of 12 artists who worked on the book, and the result is a visually polyvocal text: Each subject’s experience is given a distinct form, rather than subsumed under a single pen.

Thus, the chapter drawn by Chelsea Saunders (a freelance illustrator who contributes to publications like The Nib and Current Affairs) seems to inhabit an entirely different visual universe. Filled with clean lines and geometric backgrounds, her visual register is often disconcerting, her panels populated by figures who seem static even when clearly in motion. Her chapter follows Katie Taylor, an activist who helps former prisoners adapt to life after their release (often into countries where they don’t even speak the language). Taylor tries to help two men, both from Libya, as they navigate isolation and arbitrary legal structures after being dumped in Senegal — a Kafkaesque story where alienating linework is appropriate.

Mirk and the book’s artists put effort into making Guantanamo Voices a visually interesting text rather than a series of wordy pictures. They also strove for accuracy. In a postscript, Mirk writes that she tracked down visual references that would help the artists get details right. One senses, though, that her job would have been easier if the military had just let her take more pictures. Indeed, the comic’s commitment to visual accuracy is embedded within a larger struggle over images of GITMO, one explored during Mirk’s tour.

The first page welcomes readers to Guantánamo Bay by bluntly curtailing certain representative possibilities. As Mirk steps off her plane, an official tells her that “photos of anything toward the bay are off limits.” This restriction then multiplies and mutates. Mirk’s guide, a media relations officer named Adam Bashaw, bars her from photographing prisoners’ faces, citing the Geneva Conventions. At the tour’s end, a soldier (whose name tag and rank are obscured) goes through Mirk’s photos to approve or delete them. Then, inexplicably, Bashaw receives new instructions from an unknown source: Mirk and other journalists can’t release any photos from the prison. Mirk compares the situation to Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot: “We’re getting directions from nowhere and they all make no sense.” The prison’s position on photos is absurd and arbitrary, not principled.

At the same time, Mirk depicts military officials complaining about the images of Guantánamo that do circulate in the media. She quotes Rear Admiral John Ring, the prison’s former commander, speaking to a group of reporters: “Every time one of y’all runs a story about GITMO, it has a picture of guys in red jumpsuits from Camp X-Ray. That is not who we are… GITMO has evolved, we’re not X-Ray anymore.” Of course, this begs the question: with old and new pictures both off-limits, how are journalists supposed to picture Guantánamo (the comic itself is one obvious answer)?

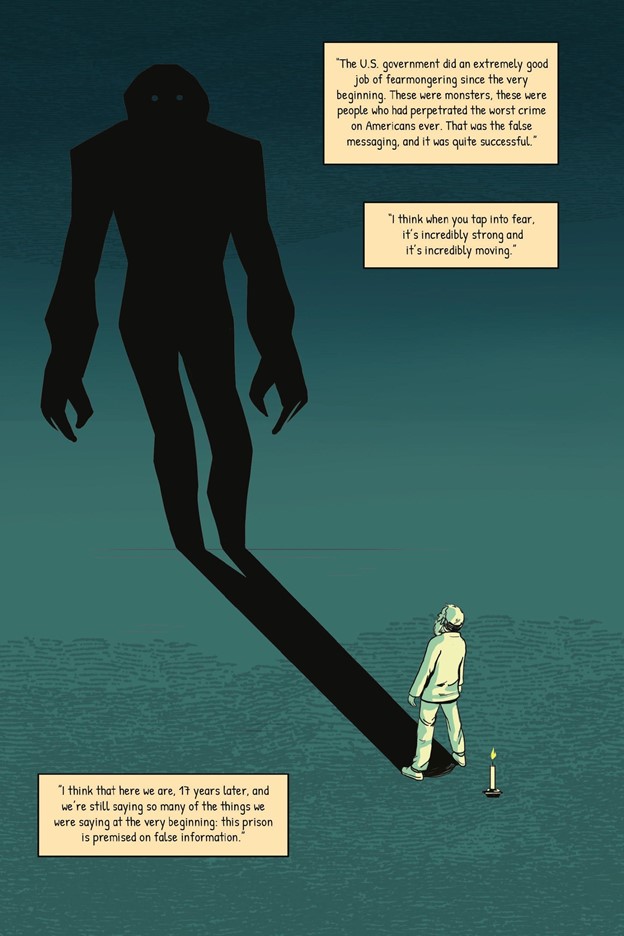

Deleted photos are a small piece of a larger problem: namely, the repression of information about America’s torture and detention programs, of which GITMO is a part. As Mirk observed in a recent interview with Fiction Advocate: “To most Americans, Guantanamo doesn’t seem like an actual place, in part because the government censorship of it is so strong. That’s the way it was designed: to be out of sight, out of mind.” Officials pressure journalists to use a sterile nomenclature that whitewashes reality: “detainees,” not prisoners; “detention facility,” not prison. The George W. Bush administration refused to reveal names of Guantánamo prisoners until forced to by a Freedom of Information Act lawsuit. The CIA actively destroyed videotapes of interrogations conducted at a black site prison in Thailand — including evidence of torture.

The combined effect of this repression makes Guantánamo into a slippery, unmanageable subject. Even people close to the prison only glimpse small parts of it. Soliders’ roles are compartmentalized: “Everyone is focused on doing their job,” Mirk observes. “But each job is just a tiny, tiny piece of a big machine.” At one point she asks Bashaw, the media relations officer, what he thinks about the morality of holding prisoners who haven’t been charged with a crime. He has “no opinion” to share. Why not? “There’s a lot more to it involved that I don’t know about, so it’s hard for me to say anything — I couldn’t give you an intelligent answer.” This epistemological crisis extends to the highest levels. In his recently published memoir, Obama observes that the Bush administration “hadn’t placed a high priority on preserving chains of evidence or maintaining clear records… so many prisoners’ files were a mess.”

Guantanamo Voices also shows how its subjects pushed back against the suppression of information. Matthew Diaz, who worked in the prison’s legal office, tried to circumvent the government’s ban on releasing names after losing faith in the prison. He hid names in a Valentine’s Day card and mailed them to the Center for Constitution Rights — an act that got him jailed and dishonorably discharged. Mark Fallon, a naval criminal investigator who anticipated future Congressional hearings, saved critical documents about the CIA’s torture program. Moazzam Begg helped lawyers gather other prisoners’ names so lawsuits could be filed on their behalf.

Still, forces more virulent than government repression linger on. “Americans are more supportive of torture now than when we were before Guantánamo,” Mirk observes, citing an Amnesty International poll. Below it, she sketches a cartoon of Trump flashing a thumbs up (“Waterboarding works!” he says). Mirk also identifies a particularly insidious cultural logic that helps sustain the prison. The book’s final sequence shows her in the airport before her flight home, sketching scenes of Guantánamo. A fellow passenger notices, and Mirk starts to explain the basic injustice that men are still being held there. But before she can finish, a man interrupts her from off-panel: “Just remember, they’re in there for a reason. They’re in there for a reason.”

The phrase is familiar. Earlier in the book, a guard tells Begg that “you’re all here for a reason. We wouldn’t have you here otherwise, would we?” It is a perfect example of the prison’s tautological foundations. The prison was built for the “worst of the worst” (in the words of former Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld). This message has been pounded into American heads. To the public, it’s not that the prisoners are in GITMO because they’re bad people. Rather, they are bad people because they’re in GITMO. The prison shreds our received wisdom about the presumption of innocence.

Even worse, this circular logic is self-reinforcing. The longer the men are held, the deeper their criminality becomes. The comic depicts a telling exchange between the Department of Defense’s top lawyer and Colonel Morris Davis, a military prosecutor at Guantánamo. As the former tells Davis: “How are we going to explain to the world why we’ve been keeping these guys all these years if they’re acquitted? No. We can’t have acquittals. We’ve got to have convictions.” This was in 2005. Sixteen years has only compounded the effect. Perhaps this explains why a Fox News host recently proclaimed that all current GITMO prisoners deserve the death penalty.

“They’re in there for a reason” is a twisted mirror of Mirk’s project. The dismissive retort is, first and foremost, an aid to forgetting. It signals a refusal to learn and erects another unnecessary barrier against understanding. It is also, regrettably, the terrain on which most discussions of Guantánamo begin and end. But we do not have to remain there. Mirk’s colorful, humanizing comic is a guide out of that dark wilderness.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply