The title of Darrin Bell’s first graphic memoir should let readers know where he is headed, as “the talk” is the term most people use for Black parents’ telling their children (especially their sons) about how to behave in the world to avoid someone—usually a police officer—killing them. Bell leans into the subject early, as he begins with a dedication—“For My Sons and Daughters”—that’s surrounded by the names of those that people in power have beaten or killed, ranging from George Floyd and Breonna Taylor to Emmitt Till and Rodney King. He follows that dedication with a brief scene from early in his life when Dobermans in his neighborhood frightened him. Despite the other children stretching their arms out to the dogs, Bell doesn’t do so, and he remains afraid of the dogs. He believes he hears them everywhere, while his brother Steven doesn’t. Ultimately, he begins to draw the dogs. This opening serves as a metaphor for Bell’s relationship with the power structure of systemic racism, as he will move through fear to use his writing and drawing to expose and fight against those in power.

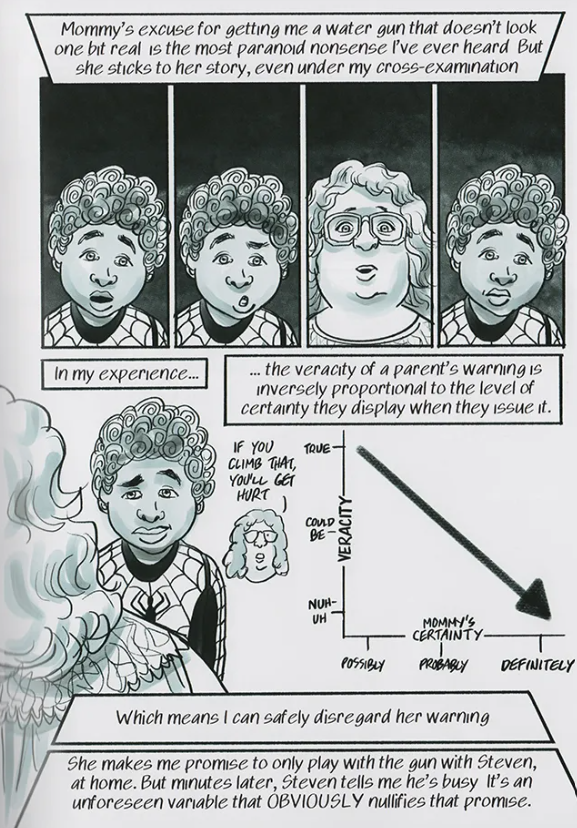

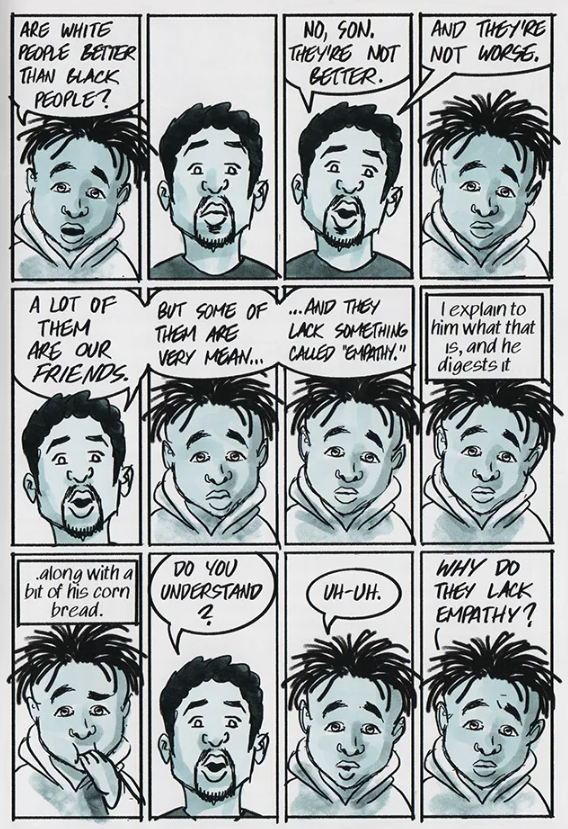

Bell is mixed race, as his mother is white, and his father is Black. His mother is the parent who is much more honest with him about race, even giving him The Talk, while his father downplays his concerns about racism. When Bell sees other children playing with a water gun, he asks his mother for one, a request she initially refuses. She gives in, though, and buys him a green water gun. When he asks why it’s green and doesn’t look like a real gun, Bell initially conveys her response as “Blah blah blah blah blah,” which he defines as “Translated from Momspeak.” However, when he goes out with the gun, a police officer tells him to drop the weapon, terrifying Bell, as he thinks the police officer will shoot him—the artwork makes it clear that’s a real possibility. He then flashes back and lays out what his mother actually told him: “Because, son…that’s what’s going to keep you alive. The world is…different for you and your brother. White people won’t see you or treat you the way they do little white boys.” He doesn’t understand what his mother has told him, but it affects him on an emotional level. He goes out and picks up a rock, looking for the Dobermans. He can’t find any dogs, though, and his mother questions him about what happened when he comes back, but he just wants to be alone and draw instead. However, he will carry that rock with him for more than a decade.

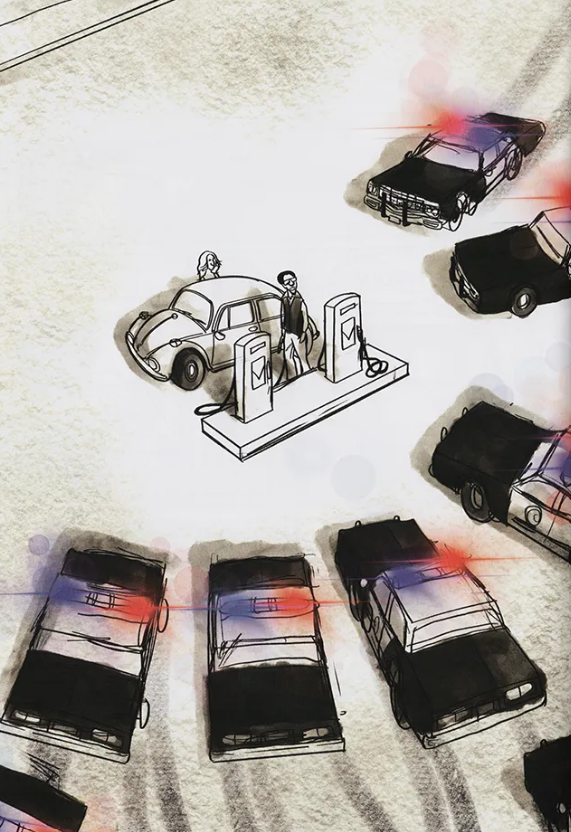

When a bully at school verbally attacks Darrin because of the size and shape of his lips, he talks to his father about the situation, hoping to understand what he should do. His father tells him a story instead, relating his meeting Darrin’s mother and their going on a drive out of town together. When they stop at a gas station, his mother goes to pay, but she sees the owner of the small station with a gun, then on the phone. The police show up, but his mother and father drive away. His mother is too naïve to be scared by the situation, and she finds it “hilarious,” but his father is clearly shaken, as the police follow them to the county line. When Bell asks what that story has to do with his situation, his father responds, “I don’t know. But I know this…a white boy’s words never made me run for my life.” Later, his father asks Bell to watch television with him, and he puts in a VCR tape of Amos ‘n’ Andy. Rather than pointing out the stereotypes such a show perpetuated, his father complains that Black people had the show taken off the air, preventing those actors from becoming as rich and famous as Lucille Ball.

Apart from Bell’s mother, his family seems to take the approach that one should simply keep their head down and stay out of trouble. His brother Steven believes people treat them poorly or stereotype them because they’re “poor, not because [they’re] Black.” Steven even discounts Bell’s story of an employee following and watching him through a store. Steven simply comments, “Yeah well, I’m sure they watch all the kids. He’s just doing his job.” His paternal grandfather seems to give him similar advice to his father, though under the guise of giving him driving tips. He tells Bell, “Stay with the flow of traffic. Follow the rules. Drive right. Be calm. You’ll be okay, Steven.” Bell suspects his grandfather knows he’s not Steven and that he’s talking about more than driving.

Such an approach leads Bell to struggle with his ideas of racism and how to deal with it as he continues to grow up. At times, such as when a police officer pulls him and his college girlfriend over, he excuses the officer’s racist behaviors and actions. When they explain they’re students at UC Berkeley, the officer points out that they’re lucky they got in before Prop 209—a ballot measure that rescinded affirmative action in California—passed. When his girlfriend Crizella points out the various ways in which he treated them differently because of their race, Bell ultimately concludes, “I think bigotry is mainly ignorance, not malice. As long as we play by the rules and be the best we can be, they’ll come around.” However, that approach doesn’t last long, thanks to two events during and just after his college years.

First, a professor accuses him of plagiarizing a paper, suggesting he doesn’t know words such as “aether.” This accusation comes despite Bell’s publishing editorial cartoons in major papers and magazines, as well as in his professors’ books. He flashes back to his previous experiences, but this time he realizes that she should know him, that he’s not an anonymous Black male to her, and she still makes this accusation. Thus, he stands up to her, accusing her of racism and threatening to draw an editorial cartoon about her and the accusation she’s making with no evidence. She tells him that he “played the race card” and that he “should feel ashamed” for doing so, to which he responds, “Professor…I don’t feel ashamed for playing the card YOU dealt me.” While his views on race are developing, though, he falls into a similar trap of those who stereotype him.

After the 9/11 attacks, he draws an editorial cartoon about the attackers, basing their images on a picture of Osama bin Laden he sees on CNN’s website. He specifically points out that the picture shows bin Laden wearing a turban, which will lead to a significant problem with his cartoon. After he publishes the cartoon, Students for Justice in Palestine at UC Berkeley begin protesting over his cartoon. What’s worse, though, is that a woman writes to him and says that “other kids, and even grown strangers, are bullying her son, even though they’re Sikh, not Muslim. She said she’s had to tell him not to wear his turban. And that he cried when he read my cartoon.” Even worse, though, the mother added, “…and I’ve taken away his water gun.” Bell realizes he has stereotyped others just as others have stereotyped him throughout his life. He goes years without drawing editorial cartoons, choosing to focus on his comic strips instead. While he draws one cartoon about the legalization of gay marriage, connecting it to the ways people spoke about interracial marriage, he only fully returns to the genre after the killing of Trayvon Martin, which comes just as Bell is about to become a father.

Bell’s work as an editorial cartoonist provides an interesting contrast in artistic styles throughout the book. Much of the work is a typical comic strip style, with enough information given to the readers for them to understand the scene, but not much in the way of detail or background. However, when Bell switches to talking about political or historical events, he often switches his style to a much more realistic view, sometimes even reproducing news footage or his own editorial work. This contrast works well to highlight how Bell’s life—the more memoir-ish part of the book—weaves in and out with the historical and political moments that help shape him as an artist and Black man. He also mirrors that combination of influences in the works he draws from or references, as he will often move from Aristotle and Oedipus Rex to Star Wars or the X-Men. His personal experiences with systemic racism feed into how he reads those larger events, while those events then further shape how he views the problem of race in America, a cycle that pushes him further as both a person (especially as a father) and an artist.

The book ends by circling back to the image of fatherhood and dogs, in fact, as Bell’s son asks him about George Floyd. Rather than avoiding the question or telling the son a story to negate his question, Bell answers as honestly as he can and gives him a shortened version of The Talk, as his mother did. When a dog threatens one of his children in the next scene, he picks up a stick and walks over to his child, picks them up and holds them on his shoulder to protect them. Bell clearly conveys a different approach than the one his father took. He will do his best to protect his children, both by being honest with them about the realities of systemic racism in America and by doing all he can to protect them from those realities. As an artist, he will create work, whether though his comic strips or this very book, to highlight that racism and work to change the systems that continue to perpetuate such injustice. His work shows the variety of ways he and others have tried to make sense of racist actions and behaviors, but he ends by showing how he has developed as a person and an artist, one who will work against that injustice.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply