Here’s a thing about me in the deep woods: I get defeated – not just lost but broken – within a few minutes of not knowing where, precisely, I might find the way out. Corn mazes, even the most complicated ones, do not destroy me in the same way that a few uninterrupted acres of trees and moss do. As such, I don’t think it’s being confused that ushers in my freakout. To the best of my understanding, the existential baggage that comes with being lost in the woods comes from three very different sources. First, the woods – both as a concept and as physical actuality – have existed long before I entered them; I am an interloper. Second, there are a LOT of stories about the forest as an ancient house of menace, at least as old as Shakespeare’s treatment of the woods in A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Macbeth. Finally, the process by which every tree begins to look the same is fundamentally troubling to the way I am most comfortable thinking, priding myself on granular obsession and disambiguation.

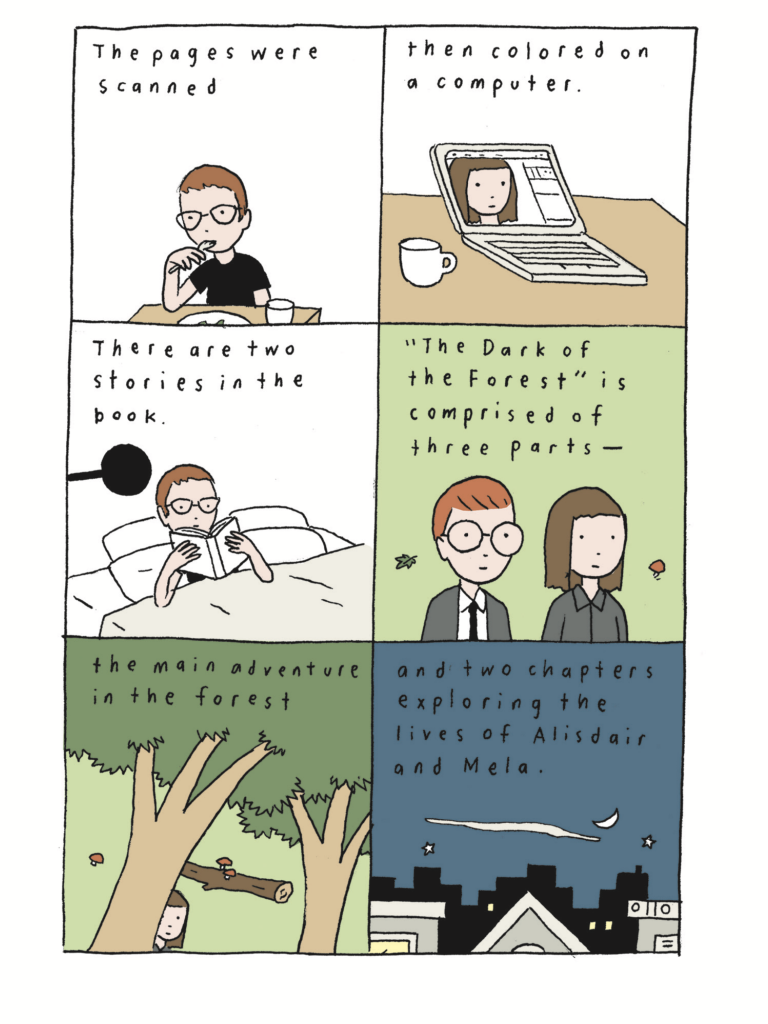

In The Dark of the Forest – beyond the title itself – Cole Johnson neither draws nor frames the woods as a source of terror or menace, even child-kidnapping goblins are mostly adorable in his hands. And yet, every major character who haunts the two subtle and engaging stories printed as a single volume here shares my interests in granular disambiguation and the complexities of naming and understanding the relationships between an ecosystem and its constituent parts. Johnson introduces his own granular obsession before the stories get started by naming, in great specificity, the tools he used to create them. In the same introduction, he draws the reader’s attention to questions of nomenclature and relationship when he clarifies that what looks like one book containing four stories is really one book with three parts of the same, non-linear story – one that shares a title with the book – and “The Garden’s Edge,” a separate story, “though I’m sure they would get on famously if they ever had the chance to meet.”

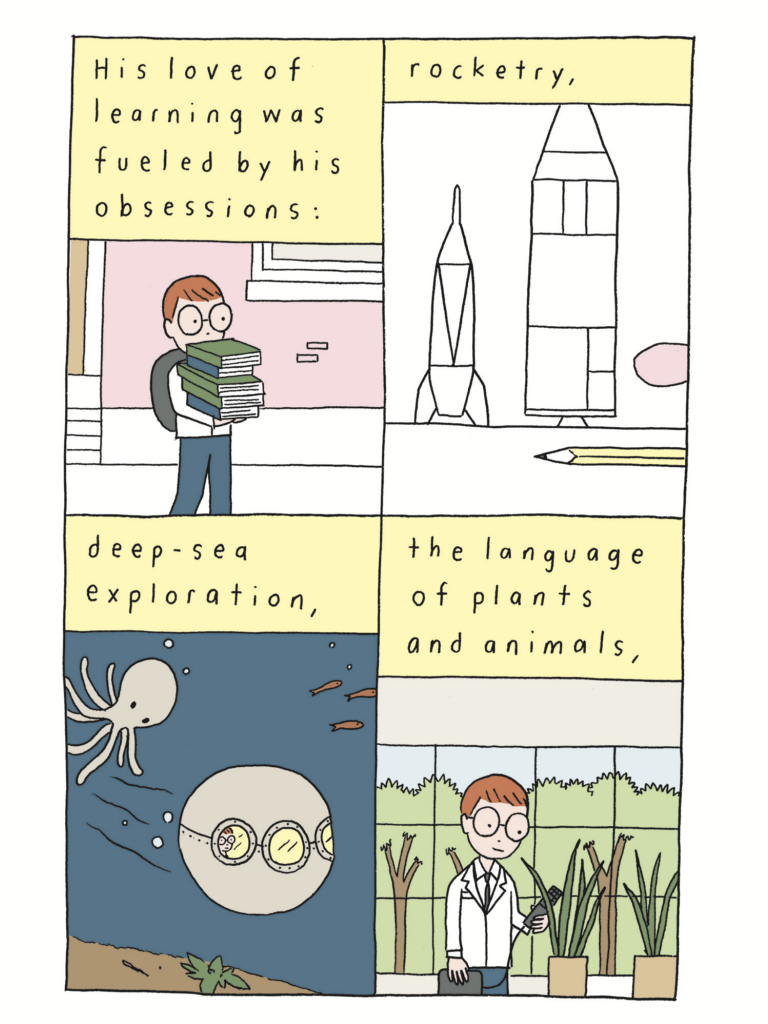

By complicating the way a reader understands the relationship between the constituent parts of The Dark of the Forest, Johnson draws the reader’s attention to the distinctions between proximity and connection. This distinction becomes increasingly important as the stories explore undefined but important relationships that are genuinely sweet without becoming cloying or twee. The three part-story begins with an “adventure in the woods” (featuring the aforementioned goblins) before backing up temporally to properly introduce its two main characters, one at a time. Alisdair and Mela are both incredibly smart with niche interests and, one imagines, fastidious handwriting, but they also share some difficulty with human interaction and the task of navigating being idiosyncratic people in a population that presumes but often fails to honor individual difference. The literal forest, which Johnson depicts mostly as cloud-shaped and kindly trees, is only one of several collective nouns depicted in these stories. Johnson makes a point of drawing the reader’s attention to apartment complexes, towns, cities, gardens, and even constellations, all of which comprise individual homes, people, plants, and stars while also redefining those individual entities as part of the larger, named thing. These various layers of compound structures provide a set of tools for the reader to use to think about the book’s primary subject: the compound structure of a human relationship.

By refraining from defining relationships, beyond stating that characters were “inseparable,” Johnson asks the reader to take stock of how they are in proximity with each other. This becomes especially important as the second and third chapters detail their lives prior to meeting. Johnson, here, defines friendship as a kind of generative proximity that provides all involved a better sense of where they themselves sit amidst the various labels and institutions that define them. The Dark of the Forest is a set of stories about people who feel most like themselves in the presence of people who they themselves recognize as individuals. Accordingly, Johnson celebrates writing guilds, folklore societies, and other places of granular obsession that allow like-minded individuals to share enough, broadly, to ensure that their individuality is noticed.

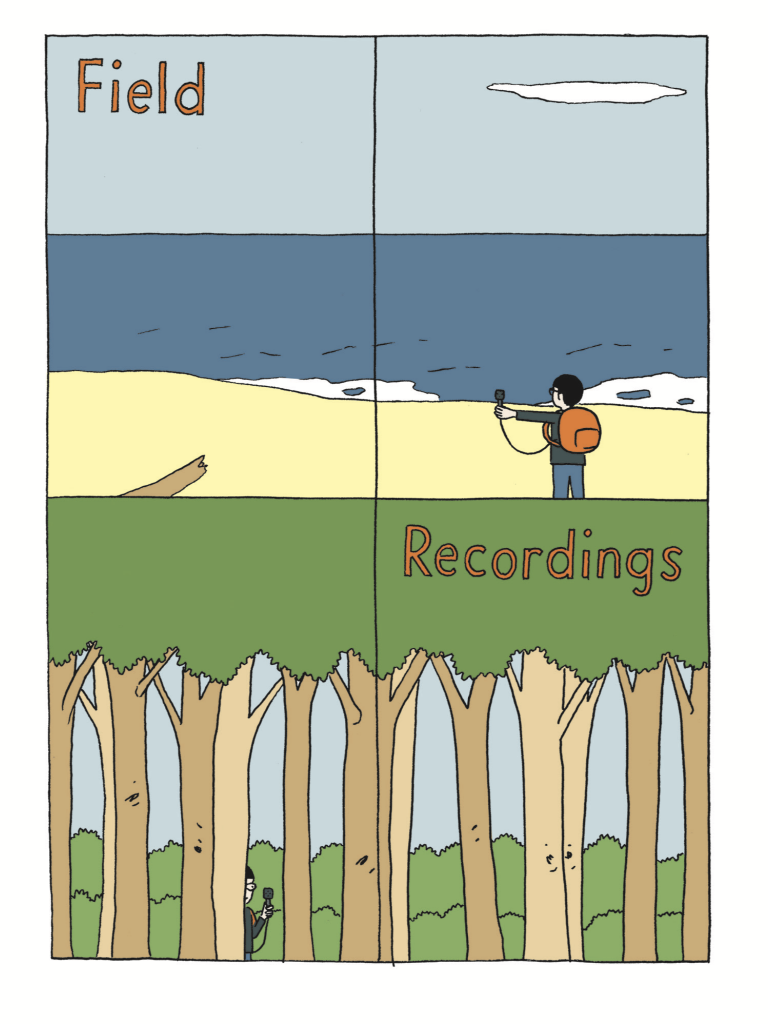

The pages of The Dark of the Forest are mostly broken into regular grids. Johnson uses a variety of voices in large blocks that function like narration in comics of the past but look a bit more like post-it notes affixed to a textbook. The physical artifact of The Dark of the Forest resembles a polyphonic research journal or set of field notes. The art style lands somewhere between comic strips from my childhood and that of an illustrated textbook. Johnson’s linework resembles, again, the kinds of careful drawing one might find in a spiral-bound notebook consistently tucked into a naturalist’s secret backpack. The art is evocative but also withholding: the characters are drawn without much in the way of facial expression which, given the thematic terrain of the story, places the reader in proximity with the characters without overdetermining that relationship. The result is that these characters exist on the page without seeming to have been placed there for narrative or dramatic effect. The authenticity of Johnson’s art comes from feeling like one is simply seeing these characters as they actually are.

The observational nature of the art extends to the plotting of the stories; they are narratives with the usual momentum a story requires, but they are also liberated from many of the demands placed upon a story as it gets ushered into print. Consistent with the art style and complicated relationship between segments, Johnson creates stories that appear to be in their natural habitat, unaware of the observer and all of the ways an observer tends to change how stories get told. In contrast to many stories about human relationships, there is little tension in these stories, even when a character falls into an abyss in the forest. What remains, however, is that these characters are pleasant to be around and the longer one is around them, the more fully their internal worlds and the events of the book take on meaning. Particularly, in the title story, Mela and Alisdair become knowable to the reader through proximity to each other. By showing them in proximity prior to providing backstories, Johnson removes the conventions that readers typically rely on to invest in a story. Spending enough time in their company, however, fosters a relationship between the reader and characters that is genuinely uncommon in comics and fiction. By the time Johnson reveals the isolation and loss that shaped Alisdair or narrates Mela’s challenges adapting to a long-distance relationship that is suddenly uncomfortable when she and her friend meet, one has already been given the tools to interpret these inscrutable characters.

True to many of the ideas put forward in The Dark of the Forest, Cole Johnson has created a comic that belongs to a number of communities and categories while remaining, definitively, it’s very own thing, one that is worth reading carefully and more than once, the way one might watch a woodland creature that habitually comes to the garden’s edge. The book is an invitation to see anew, to get lost in the woods without worrying about whether or not the dark of the forest is all that different from the dark of a movie theatre or the dark of anywhere else. One doesn’t read The Dark of the Forest so much as one hangs out with it to watch whatever is on television or put together a puzzle. It is a comfortable book about uncomfortable people and therefore thrilling in the way that being in the room with someone you like is thrilling, particularly if you rarely enjoy the company of others.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply