You are sitting at your house and you are about to open a book.

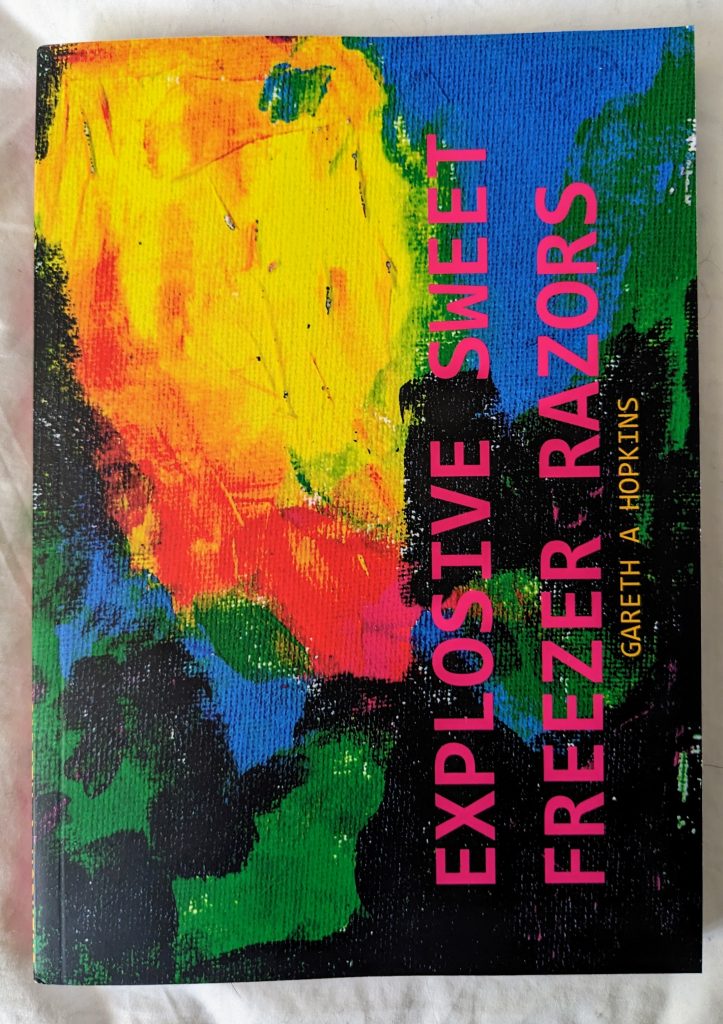

What can I make of something like Explosive Sweet Freezer Razors? I am in somewhat of a pickle because all my usual “tricks” of engaging with a work of art in a critical fashion are like water off a duck’s back in this case. I can’t explain “plot,” I can’t explore “character,” I can’t engage with “context.” So let us, me and you, try to wrestle a measure of control by going back a bit. Let’s establish some unarguable facts. This will help me find some stability; maybe it will even help me write this review. Unlikely, but possible.

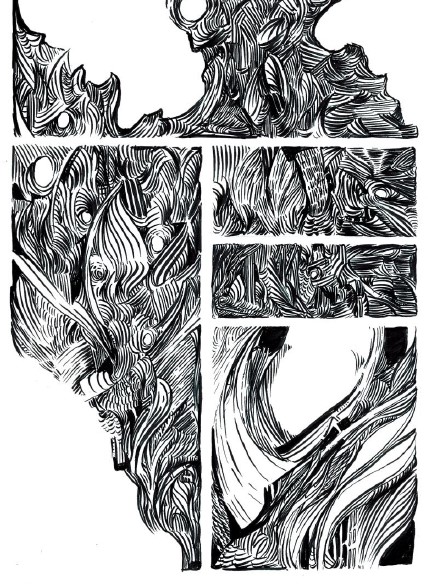

Explosive Sweet Freezer Razors is a collection of ten stories (no, wrong, the word “stories” does not give the right impression, ten “comics”) by writer-artist-person Gareth A Hopkins. Each piece is a series of abstract images, some of which were originally made by other people (Hopkins’ wife, Hopkins’ children) before being painted over. Over each such collage of drawings, a narration is overplayed. Some of the narration is original, and some (like the paintings) are based on previous works, the poet Erik Blagsvedt is mentioned as an inspiration.

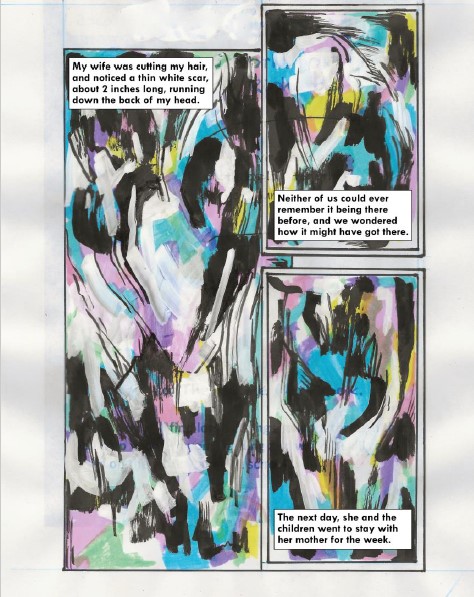

The written sections, which I will focus on now simply because it is “easier” for me to engage with, moves between the fantastic and the mundane. In “Thunders” Hopkins writes about spending some time away from his family (actually, they were away from him at the time, but the result is the same) in a rather dairy-ish fashion: “I played excessive amount of video games, read crime novels in the bath, and slept with the bathroom light on.” This sounds like the type of thing that would appear in your standard-diary-comics (quite possibly the kind to be posted on social networks to a cheering “he’s just like me” response before being swept away by the tide of history). However, there’s nothing about the mad whirling of colors that accompanies these words that evokes diary comics. Like one of these strange moments in which the captions for one movie suddenly appear in another; as if your brain and eyes are switched to two different dimensions.

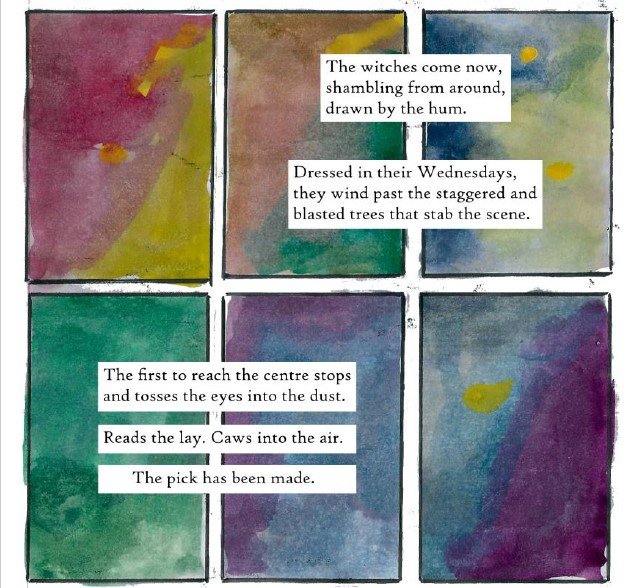

Compare this to “Tuesday’s Salted Curse” with words that suggest the mystic and the weird: “The witches come now, shambling from around, drawn by the hum. Dressed in their Wednesdays, they wind passed the staggered and blasted trees that stab the scene.”

I note how evocative the language is in this scene, it brings to mind a story the images don’t tell. At least, not directly. The trees “stab” the scenery around them, making a gaping, oozing wound in creation. The caption boxes containing these words are not located in any single panel, they are both positioned across two different panels, a recurring feature throughout the collection (just like the works themselves hover between the fantastic and mundane). In Explosive Sweet Freezer Razors there are no clear borders between the aspects of one’s life, everything is part of this pulsating unclear “whole.” Both the style of painting, and the way they came to be (based on, built upon, the work of others), signify this understanding. That we can’t decide where one part of us ends and other starts.

And yet, despite the abstract nature of the art itself the book is easily recognized as a “comic book” thanks to the clear panel separation. There is still a sense of flow, of continuation, rather than a series of separate images. And when one looks deep enough into it, one begins to see things. In the above-mentioned example, one of the panels features a mix of sickly green colors, around them are swaying greys and in the center a yellow dot. Is this the sun in the grey clouds, hovering above the “blasted tress” mentioned in the narration? Could be.

You are still reading the book

The final panel of this page is a near-equal mix of blue and purple, with another yellow dot. Except for this time, thanks to its position between the colors, it appears to me not as the setting sun over a dead landscape, it’s an eye. An eye in half a face. Looking at me. The book is looking at me. Or I might be imagining things This is not intentional, but my mind is doing the thing human minds do all the time, seeking patterns. Making sense of everything, quite literally making it even when it’s not there to be found.

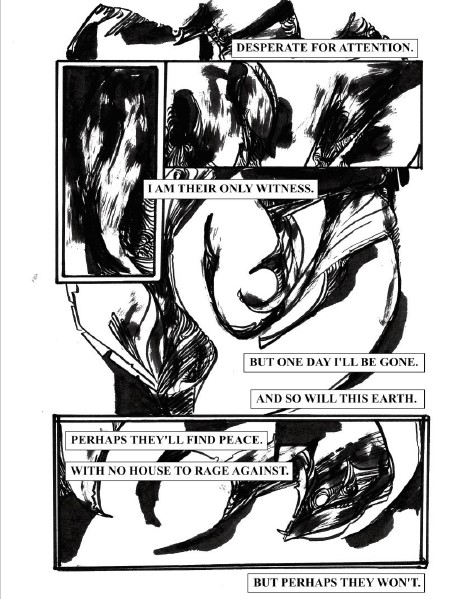

My favorite piece of the book is “Not This House,” which is composed of black drawings, they appear to be mostly brush strokes, over white backgrounds. It’s like a series of moments of something being born, something coming into being. Like life being formed out of the ether of creation. I see in it faces and limbs and features and bodies and expressions and anger and desire and loathing and loving and seeking and … never finding. There’s never a sense of a proper climax to the piece. It is a work that feels truly alive in the physical sense of the word, not the usual illusion of movement that is a necessary component of comics. It feels alive because we see it in bits in pieces, always in the thickest of movements rather than above it; a recurring feature of Hopkins’ work – the sense of being in the middle of something greater than ourselves.

Whatever it was seeking to be born (some rough beast, perhaps?) appears to still struggle when the chapter is finished. The final caption box appears below the final panel: “But perhaps they won’t.” Just as there is a beginning and end within each panel, the lines swishing and swirling like a mad dance, so is there no beginning and end to “Not This House,” it’s forever occurring and recurring.

You are still reading the book

This, I should point out, is not the actual story being presented here. According to the official description on the Gosh Comics Website – “In NOT THIS HOUSE you’ll meet a ghost, and the house that it haunts.” This is why the works of Hopkins oftens frustrate me, because I see something in them that is (apparently) not there. Because that means I was “wrong.” Have I reached the limits of myself, as a critic and person, again? Myneed to make sense of things? But this book is not a puzzle to be solved. This is not a review that can be finished by triumphantly laying down the meaning I uncovered in the book.

Except “frustrate” does not mean “hate.” And “wrong” is (ironically enough) the wrong word choice. Explosive Sweet Freezer Razors frustrates me because it forces me, at every turn, to look away from the book and into myself. It offers no easy answers, it often offers no answers at all. The book is not a mirror, but a window, and through that window, each of us will see something else.

To engage with Explosive Sweet Freezer Razors is to ask what each piece makes you feel at a particular moment. The little sense of giddiness when the black and white in “A Hill to Cry Home,” begins to become intermixed with splotches of color. The sensation throughout “Patelburn” of a bird in flight, great wings opening slowly, like seeing into the bone structure. The silent landscape of “The Valley,” something that Moebius wouldn’t have drawn but would have thought of. This is what I see in it now; this is not what I saw in it the first time I read it. This is not what I will see the next time I’ll read it.

You will never be done with the book

How can I write a “review” when I am so unsettled about how I feel? I cannot. I am still digesting Explosive Sweet Freezer Razors, I might never stop.

The book will never be done with you

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply