Almost anyone who browsed young adult or fantasy novels in the 2000s (or, even now) is familiar with the ever-present phenomena of the Warriors series. Beginning with the release of the first book, Into The Wild, in 2003, the book series’ popularity rapidly expanded both in its intended age demographic (ages 8-12), along with many teen and even adult readers. Sometimes controversial due to its handling of adult topics often brushed over initially by parents due to the covers featuring fairly innocuous cat artwork (the first series alone features child soldiers, murder in order to rise in power, graphic disemboweling, and plenty of throat-slitting, face-removing, and kitten death the series is known and loved for). What exactly is so appealing about Warriors, now 70+ books strong, with a fanbase still popular and thriving to this day?

A large portion of the fanbase is based around, surprisingly, artistic interpretations of the characters. The original Warriors series has a fairly typical artistic presentation; covers featuring the main characters, as well as a few minor black and white illustrations to separate chapters. However, the portion of the fandom surrounding fanart and animations exploded after the release of the Lost Warrior, the first book in the Graystripe’s Adventure manga series, in 2007. Produced by Tokyopop in collaboration with HarperCollins, who owns the rights to the original Warriors series, the three-book manga series details what happened to Graystripe – one of the main characters of the first Warriors arc – after he’s captured by humans, referred to by the cats as ‘Twolegs’, and taken away from his life in the warrior Clans to be a pet. The books, like the vast majority of the Warriors manga books, are illustrated by James L. Barry, also known for his independent online comics, such as Lost Horn. They continue to be written by the main series’ authors – which is a conundrum in itself, as the ‘Erin Hunter’ pseudonym was originally used by three writers at the start of the series, but has accumulated members, notably Wings of Fire author Tui T. Sutherland, in recent years.

The charming illustration style, fast-paced story, and all the elements from the main Warriors series that made it explode in popularity among its target audience of middle schoolers (talking cats! Plentiful violence! A group of buddies disrespecting authority to do what’s right!) made the Warriors manga series an overnight success. Publisher’s Weekly stated in regards to the Lost Warrior that “Many little (and perhaps some larger) girls will find this kitty fantasy irresistible,” but also noted that “there are no plot surprises in this story of a lost hero”, likely acknowledging what many critics and parents were off-put by – while the Warriors novel series certainly has its pitfalls, it manages to engage many readers for chapters; the Tokyopop manga, in comparison, are often easy-reads for half an hour or so, and tend to focus less on compelling new plot points and more on delving into underdeveloped backstories, something that may not interest all readers, particularly those not heavily engaged with the Warriors universe.

On the other hand, plenty of aspects of the Warriors manga books received praise from critics, even for aspects one might not expect coming from, well, a cat book for kids. A different Warriors manga series, titled simply Tigerstar and Sasha, follows the story of an abandoned housecat named Sasha who falls in love with the strange Tigerstar, who tells her of his life in brave battling Clans – while keeping her in the dark about his tyrannical rule over ShadowClan and a growing headcount, taking down any cat who stands in his way – his goal being to triumph over all four clans as leader. Publisher’s Weekly regarded this series more warmly, praising the second book in the series for highlighting Sasha’s bravery in leaving the powerful Tigerstar due to his “growing violence”, an important notion for young, primarily female, readers. Illustrated by Don Hudson, this series has a slightly more detailed, less simplistic art style than Barry’s, although this series has less of the action sequences that Barry excels at depicting.

One of the most popular of the Warriors manga arcs is Ravenpaw’s Path, a four-book series following Ravenpaw, a former ThunderClan apprentice who left Clan life after witnessing his mentor murder his Clan’s deputy in order to take his position, and Barley, the cat whose barn he took refuge in, after their separation from the Clans detailed in the final book of the first Warriors novel series.

This series received heavy praise from fans due to the belief that the series, released in November of 2009, depicted the first gay couple in the Warriors universe; Ravenpaw and Barley were shown to be extremely close to each other, and, while no statement was ever made within the books confirming or denying that they were intended to be mates, a Facebook post made by Victoria Holmes, one of the authors behind the Erin Hunter pseudonym, stated that the two are in love. While the comic series depicts nothing but a happy end for the two cats, living out their days in peace in the barn, in the novel series Ravenpaw later dies laying on Barley’s paws; when Barley sees his friends in the Clans again, he tells them he has missed Ravenpaw every day. Despite being released over a decade ago, the series remains ever-popular among fans; recently, fans came together to redraw one of the comics in its entirety, each page done by a different artist, the project hosted by @harriertail on Tumblr.

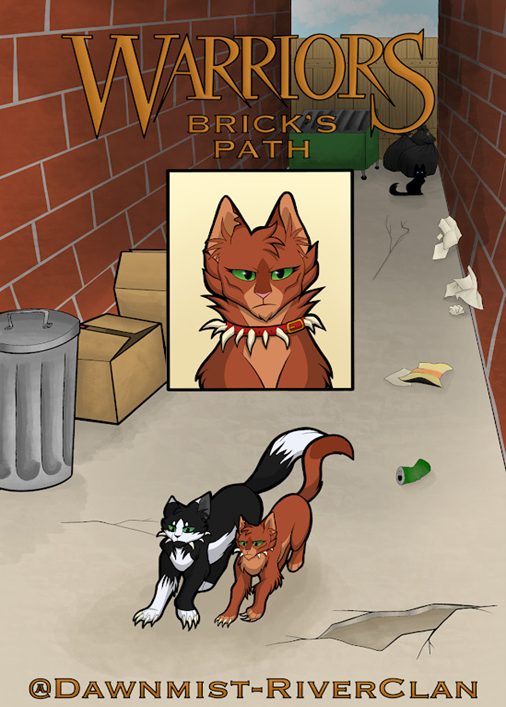

One of the biggest portions of the fandom surrounding these comics has little to nothing to do with the actual Warriors series characters. Many popular comics related to the Warriors fanbase are barely relevant to Warriors at all – fan-made comics, set in the Warriors universe but built around the stories of original characters, are thriving even nineteen years after the release of the first Warriors book. Additionally, some fans create comics based on ‘rewritings’ of the series, or just exploring parts of the books that weren’t detailed in canon. While, of course, these fan-made comics can’t be published – original characters or not, the universe and worldbuilding aspects still belong to Erin Hunter – that doesn’t mean they aren’t read and beloved by many, hosted on various sites like Twitter, Wattpad, and others to be enjoyed. Some even find these stories preferable; they may have fewer characters to make things confusing than the sprawling arcs of canon Warriors books, or more adult plots than the original series. While the original books certainly depict violence, fan-made comics have the freedom to draw gore as explicitly as desired, as well as darker plots that wouldn’t be able to sneak into even a heavier children’s book.

The sprawling universe of Warriors, lovable and varied cast of characters, and multiple talented artists who contribute to the manga series (which continues to be active – the most recent Warriors manga was published in 2021!) entices readers of all ages, even those who might not want to admit they shed tears over fictional fighting cats, and likely will for generations to come. Despite what may appear to be just another bland animal-centered kids’ story with too much action and not enough plot, the Warriors manga series surprises with loss, love, and plenty of heart.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply