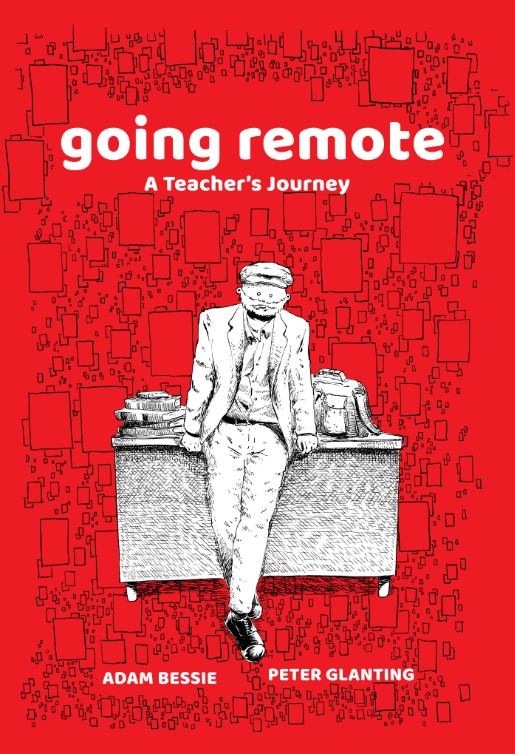

Adam Bessie’s graphic work tells the story of his return to teaching after time off due to a brain tumor, a return the coronavirus pandemic quickly cuts short, at least in a face-to-face setting. Bessie is a teacher who clearly cares about his students and the profession (and promise) of teaching, so being away from the classroom was challenging for him; teaching online is a shadow of real teaching, at least the way Bessie approaches it. He uses his story to connect to larger ideas surrounding access to education, race, equity, and privilege, among other subjects, though I found myself wishing he would have gone deeper into each of those issues, given how deeply he believes in them.

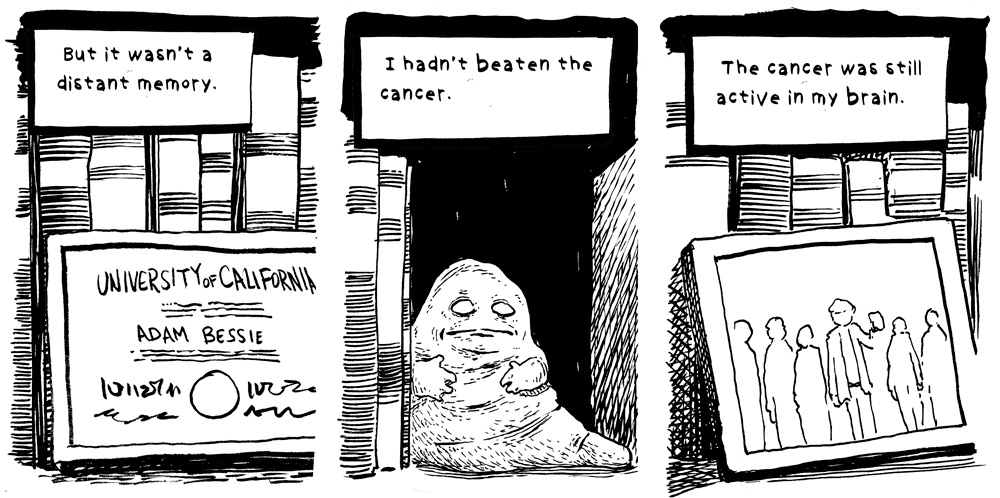

Bessie begins the work with a bit of misdirection, as the first section is titled “The Return.” Given the overall title of the work—Going Remote—the reader expects that Bessie is returning to the classroom after the pandemic, not before; however, he quickly shares with the reader about his multi-year struggle with a brain tumor. Bessie uses that return to talk about the joy he finds in his students and in teaching, as he lays out several scenes of students bustling across the campus talking with one another, as well as conversations students and he have in the classroom. He’s an English professor, so it’s not surprising that he thrives on student discussion about books the students have read, but also the ideas that come out of those books.

Not only is Bessie an English professor, though, he’s also a professor at a community college, and that location is important to him on two levels. First, he values the idea of community, and he wants to create that in his classroom, on the campus, and in the world. He works to include all students’ voices in class conversations, and he wants to use his voice in the world beyond the campus. This focus on community is why he struggles so much when the pandemic hits and education shifts to remote, a situation he feels all the more directly because he’s immuno-compromised due to his cancer treatments.

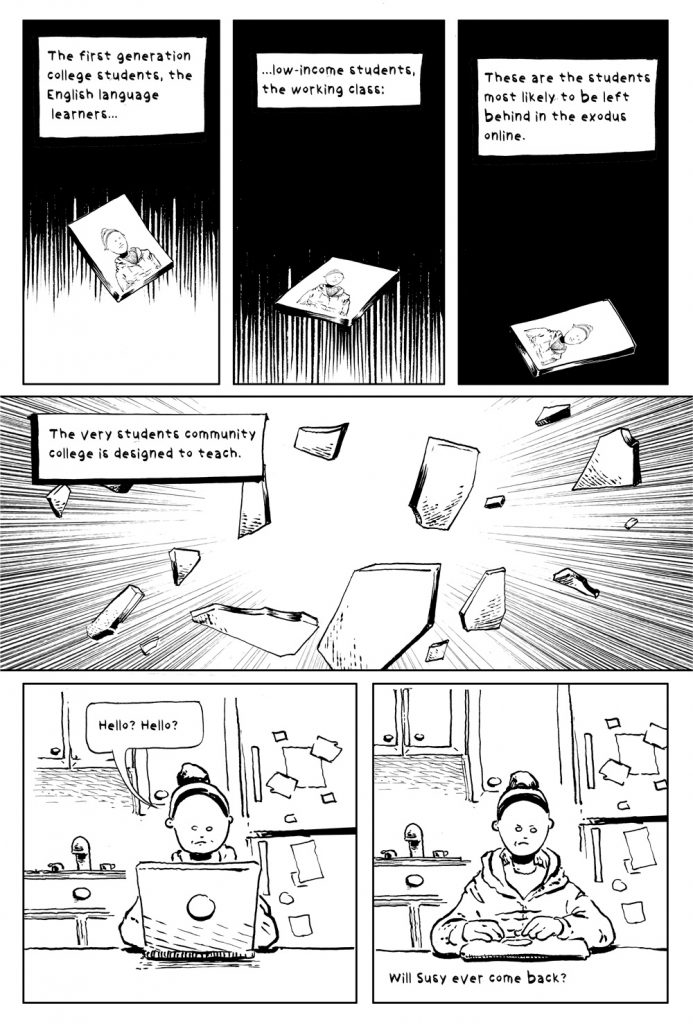

Bessie believes all people should have access to education, should they want to seek one, and he believes community colleges play an important role in that part of society. In his return to campus, he reflects, “Our education is designed like a waterway. An aqueduct, a constructed thing of concrete, and policy through which students are supposed to flow. I was drawn to teach community college by the idea of open access…by my hope that neither class, race, background nor disability would prevent students from joining us…that all who joined would have a more fair shot in an unfair socioeconomic system.” He is a teacher who believes education can change lives and the community college model can effectively change those lives for all.

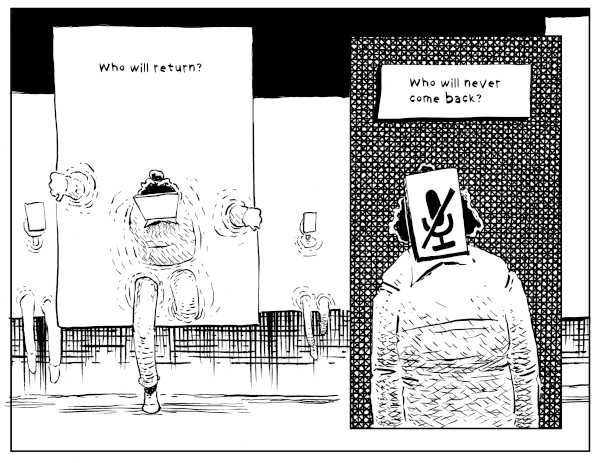

Not surprisingly, then, when the pandemic hits, he reflects on the injustices already present in society that the lockdowns both highlighted and exacerbated. He thinks about those students who disappear from his classes: “But from what I could see, the students that were most likely to disappear…the most likely to fall into silence…were students like Jamila,” the only black student in his science fiction class. He wonders if the college is complicit in her disappearance and if he is. He thinks about the students who don’t have access to the internet, who don’t have room where they live—if they have stable housing—to fully engage with their online classes, as well as those who are continuing to have to work during the pandemic, putting their lives at risk. He sees the conflict between the ideals the community college system professes—the same ones many Americans profess—and the realities of how the power structures work to deny marginalized groups access to those ideals.

He recognizes these problems don’t cease to exist whether the students are online or on-campus, as he receives emails from students talking about their emotional breakdowns and how they are struggling to cope with tragedies, but also day-to-day life. He sends alerts to people who could possibly help, as he knows he doesn’t have the training to deal with such situations, but he also recognizes that people are cut off from one another—the absence of real community—when they need others the most. Even when they do return to campus, all of them—students and professors alike—struggle with how to be human with one another.

He even takes his son to Oscar Grant Plaza in Oakland, where they live, to show him where people marched in the summer of 2020 in protest over the killing of George Floyd, while also explaining about Oscar Grant, for whom the plaza is named. He lists the names of the murdered, ranging from Aaron Bailey to Zella Ziona. He makes sure his son knows who Nelson Mandela is, as there is a bust of him, along with a quote that sums up his own ideals: “Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” And yet he recognizes that racism (and other forms of bigotry and prejudice) is, as Zadie Smith says, a viral illness, contempt. He knows American systems are infected, but he also wonders if he is and if he can pass that along to his son. It’s not a coincidence that he begins the following section with his doctors finding a white space on his latest brain scan.

Glanting’s artwork reflects the focus on community and access that Bessie’s story raises. He uses a cartoon-like style rather than a photo-realistic approach, which, even for those who aren’t familiar with the language of graphic works, makes following the story easy. In an interview at the back of the book, Bessie talks about Glanting’s role in helping to shape the story, in fact: “…I feel it’s as though we’re in a two-person band, you know, where like I’m the singer and play drums and Pete’s on guitar. He’s got one of those guitars with two heads on it and he’ll be riffing on both of them. But, seriously, I think a lot of improvisation went into the construction of this book.” The best example of that collaboration shows up when Bessie learns his cancer has begun to grow again, yet he has exhausted all of the conventional treatments. When Bessie writes that he’s an experimental subject, using that metaphor to talk about how everybody was effectively a participant in an experiment when they returned to campus after the pandemic lockdowns, Glanting has a photo-realistic picture of Bessie on a computer screen. At his most honest and fearful moment, he’s not a cartoon character, but a person who might die of cancer, a person the reader can see as he is. Bessie and Glanting show readers who Bessie is, so they can see him as he wishes to see his students.

My main critique of the work is that it feels like Bessie could have gone deeper into each of the ideas he wanted to explore, whether that’s community or equity/access or even his personal life, which we see glimpses of, but don’t get the full development of. Thus, the book feels a bit like he’s moving us from one scene to the next to the next—almost an “and then…and then…and then” feeling—without as much reflection as he could bring. Given that the work is so tied to a particular time and significant themes, I had hoped to see more exploration of those ideas.

There’s no doubt Bessie cares deeply about the reality of his students and America, especially those on the margins and without power, and he clearly communicates that concern, as well as his belief in education. However, providing the reader with more background and reflection on those issues, as well as thoughts about how we move forward now, would have made for a more rewarding work.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply