December 12th, just after 11 P.M., outside the Metropolitan African Methodist Episcopal Church. More people piled into the garden of the church, stomping on the sign and slashing it with knives. Amid the frenzy, one of the Trump supporters removed another placard from a different display. It had a verse from the Bible: “I shall not sacrifice to the Lord my God that which costs me nothing.”

Luke Mogelson, “Among the Insurrectionists”

Almost 66 years before a mob stormed the U.S. Capitol trying to halt the procession of government, Lolita Lebrón and three other Puerto Rican nationalists struck the Capitol building, coming in through the spectators’ gallery and firing shots into the House chamber. Five representatives were wounded. Lebrón, for her part, fired into the ceiling and was tackled while trying to unfurl the Puerto Rican flag. The flag was contraband: display of it had been made illegal by a 1948 “Gag Law,” which also banned singing or whistling a tune of Puerto Rican patriotism or criticizing the U.S. government. On arrest Lebrón stated, “¡Yo no vine a matar a nadie; yo vine a morir por Puerto Rico!”: “I did not come to kill anyone; I came to die for Puerto Rico.” A photograph of the moment captures Lebrón, iconic, the revolutionary as Lauren Bacall. Pair the words and the image and we have a single panel – a moment cut from time and context – and a human mystery of that image-moment: who gives – that much – to what?

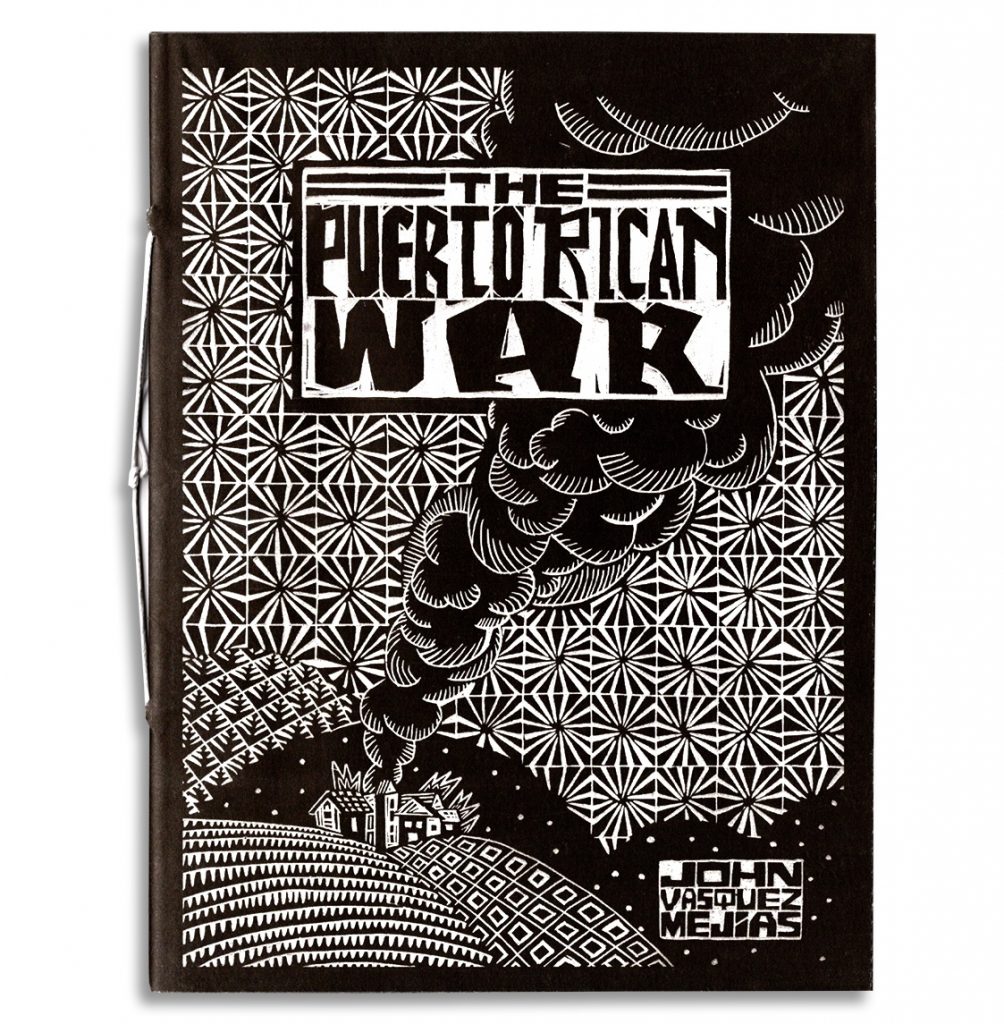

The Puerto Rican War, John Vasquez Mejias’s tale of the struggle for Puerto Rican independence, makes the mystery luminous. Mejias’s chronicle is centered around the uprisings of 1950 in Puerto Rico and the attempted assassination of President Harry Truman by two Puerto Rican nationalists. Mejias’s tells the story in 96 intricate and stunning pages of woodcuts, a labor that took the full-time public school art teacher around 6 years to complete. It should now be carved in stone as a monument – though I wouldn’t dare ask Mejias to do it himself.

The epic begins in the deep time of Puerto Rican resistance to colonialism with a 1598 poem, “Revolt of the Borinqueños,” a statement of the original crime which reverberates throughout the body of Mejias’s narrative:

While suffering such evils night and day we serve these fogners [sic] in our land of birth and our only freedom is we may work their mines and till for them the earth…

And it is they who possess all and leave us to our death here in our land that was always our own where we were born and where we have grown.

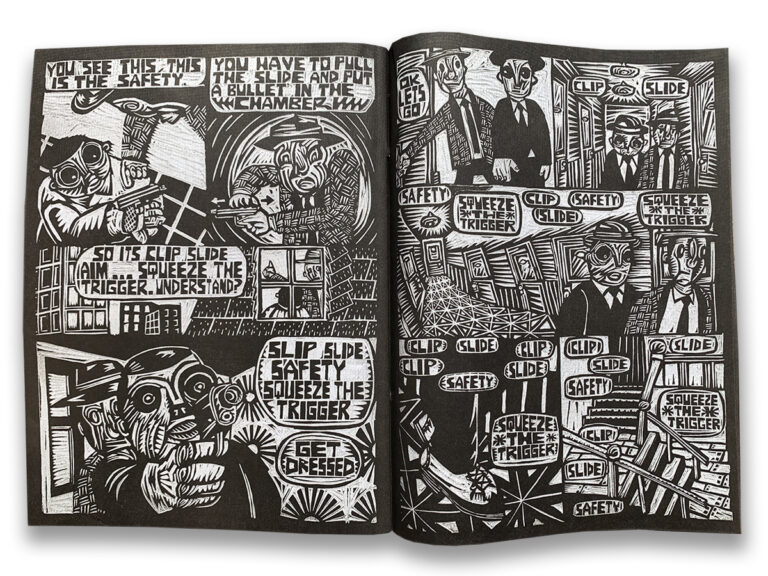

Imagine dragging a gouge across a plane of wood to produce a line. Imagine knowing how to score the surface to pull a curve against the wood’s grain. Imagine the skill needed to feel how deep the gouge must plunge to produce a fat line or a fine one. To achieve just a block of text illuminated with the flora of Puerto Rico, Mejia’s woodcutting would have required him not just to inscribe the words, as a comics letterer would, but to meticulously carve away the negative space around each letter so that only the raised surface of the text was left to appear. Woodcut prints pre-date even movable type and were thought to be the first form of print-making. The canvas of a woodcut printmaker is the surface of a plank of wood, whose grain can both constrain the movement of a carving tool and be incorporated for effect into the image. Albrecht Durer, one of the most famous woodcut artists in the 15th Century, was able to achieve incredible, detailed linework in his efforts to translate the Bible into images easily understood by the public. More often it became popular because it was a cheap and easy method of printing early in the development of mass communication technology. In Europe, it was used to reproduce religious imagery and teachings for popular indoctrination. It’s with a fitting sense of historical irony that Mejias’s method of art was also used to produce some of the earliest examples of woodcut books: instructional manuals printed in Spanish and Nahuatl for use of Catholic priests in the conversion of the Aztecs. But if the woodcut print could be used for colonization and domination, it stands to reason that it can be used to undo those processes as well.

When one thinks of woodcuts, one thinks of the iconic: a moment of time frozen for eternity, but while each page of Mejias’s comic is made up of gorgeous panels, it is immediately a work bursting with excitement and movement. The conspirators of revolution and their betrayers practically vibrate with life, one could almost wipe the sweat from the brow of a nervous would-be revolutionary. In an early scene of a police-nationalist shootout, the curve of a cobblestone road sweeps the reader’s eye across a tableau of violence and destruction. Far from a splash page, it’s a whirlpool that pulls you from one page and then back again. Though the comic is in black and white, when Mejias renders the landscape of the island of Puerto Rico, one can practically feel the sun radiating on the fields and the ocean waves crash through time-eroded caverns.

The appeal of the woodcut is easy to see here. These same kinds of expressive qualities made the wordless Biblical imagery understandable to an illiterate audience. It was a similar kind of relief printing employed by José Guadalupe Posada in thousands of illustrations meant to reflect the social upheaval experienced by Mexicans in the time before the Revolution in 1910, images so iconic that they were easily understood even by people who couldn’t read – and so enduring that we will still see Posada’s influence in calaveras everywhere today. When Emory Douglas took over the illustration and design of The Black Panther, the newspaper of the Black Panther Party, the style he aimed for was that of the woodcut.

Constrained to black or white, to the wood’s surface or its negative, these limits channel creativity to the surface of a single plane where it explodes into innumerable, various effects. Text and image reside side by side, so close that Mejias can turn almost every utterance into a pictographic effect. When one of Truman’s assassins has to learn how to work a new gun, the litany of steps beats through his – “Clip. Slide. Safety. Squeeze the trigger” – until it fills the page and blocks out thought of anything else. Whether or not the history Mejias tells is familiar, the people in it, however brief their part, become real, emotive, expressive, and tragic.

The woodcut didn’t always stay in the realm of mass-produced indoctrination. It was a favorite of German Expressionists, who were attracted to its accessibility and affordability while it lent itself to a moody imagery that was able to capture the feeling of poverty and grief felt by a country experiencing the effects of the post-WWI depression. American artists like Lynd Ward turned to the medium to produce some of the first “Wordless Novels,” which seemed to boom in the same era in the United States. This liminal status, between fine art and mass communication, is felt in the final object that Vasquez delivers. Printed on newsprint and bound with a stitch of string, it feels both like a pamphlet delivering a revolutionary tract of the moment, and something held together with love.

Newsprint is fitting. Showing the Puerto Rican nationalist revolts in 1950, including the uprising in the town of Jayuya, a massacre of nationalists by police at Utuado, the narrative swings into focus around the figure of Pedro Albizu Campos. Campos was one of the leaders of the Puerto Rican independence movement, a gifted speaker, who had led strikes, political parties, and decried American medical abuses of Puerto Rican patients. During the uprising, his home and residence were surrounded by police, who opened fire without warning. When a comrade tried to enter Campos’s apartment, he was summarily shot by police. The next day during a truce, Campos asked to see the newspaper. It carried a quote from President Truman, dismissing the murder “An incident between Puerto Ricans.” Campos’s face darkens and turns away as he realizes just how invisible Puerto Ricans are to the United States, how little they matter to people like Truman, how light the death of a friend by police bullets is in the eyes of the world.

Here, though, each ounce of force applied in the subtraction of each bit of wood is visible. With this document of love’s toil given to us by John Vasquez Mejias, maybe we are finally getting the news.

Leave a Reply