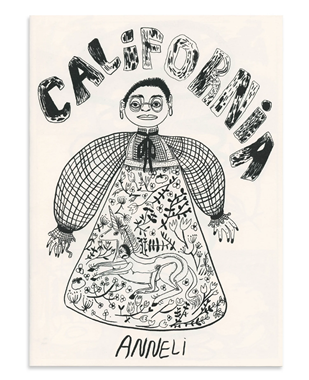

From the cover of Anneli Sanaye Henriksson’s CALIFORNIA, (published by Caboose Press) a figure dolled up in cottagecore frock, checkered sleeves, and blackened nails looks bleakly out at you. Individual lashes have been drawn, toylike, under their eyes; a worm dangles from their left sleeve. On the front of their frock is a unicorn, like the one from the Cloister tapestries, and inside the unicorn is a yelping semi-human figure with feathery leg hair like a millipede’s legs, or like cilia. The skin on their hands is marked with dots: dirt, rash, or an assortment of punctures? (Soil, itch, or pain?)

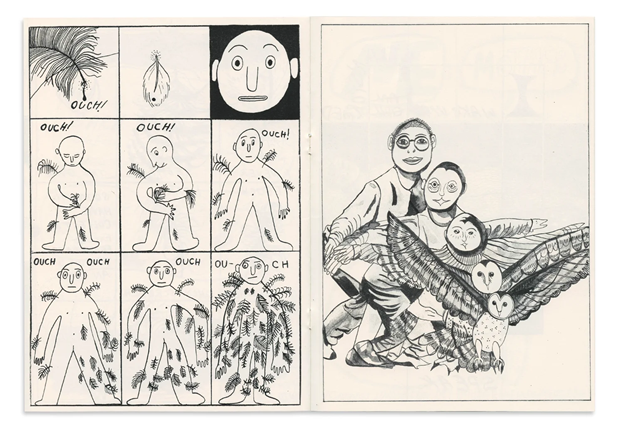

The cover has this kind of density of visual particulars that exists nowhere else in the comic. Inside, abstraction reigns, chopping the body from the cover into lumped parts and simple shapes, and giving over sensation to illegible, brushy textures, botanical designs, handwritten text. The comic begins with a clarification: “This is not my home.” The narrator takes miserable little walks around their mother’s garden, collecting feathers they find “in the clover / under the hinoki / behind the shed.” They slowly accumulate enough feathers to “build an owl” out of their own body, inserting the feathers like needles into their body (“OUCH! / OUCH! / OUCH!”) until they transform, in a page spread that plays on Animorphs covers, into a barn owl.

Although this posthuman ending of transformation and flight seems to chase away the entrenched misery of the narrator’s life, Henriksson complicates the fantasy. Or, more precisely, she doesn’t allow us to keep it. The comic is insistently a story of circularity and accumulation, not of uncomplicated cures or escape from pain. The protagonist gets their owlish transformation only by stockpiling feathers collected in circular laps around the garden; they insert the feathers painfully into their skin until their body is covered in them. In the last panel, the feathers start to resemble a dysphoric, alien version of body hair.

I can’t totally explain why this comic feels so Asian American (even if you didn’t know the artist)––it’s in the vibes, the specific brattiness, the abject humor. But I do want to explore the difficulty it raises in reading it representationally; its representational obliqueness at once raises and diverts questions of race. After all, any attempt to identify this character gets playfully circumvented by the cartoons themselves. What’s there to racialize (or indeed gender) in all this abstraction?

That’s not an entirely rhetorical question. There are two kinds of cartoon eyes drawn in this comic––round, egg-like eyes expressing a kind of jolt, and mask-like, almond-shaped eyes whose expressions are more poker-faced. Although both are familiar cartoon shapes, the pointed, “almond” eye shape interestingly captures both a representational and an abstracted attitude. It’s one of the first things you might learn not to do when being taught observational drawing. (“No one actually has almond-shaped eyes,” my boyfriend recalls a drawing teacher say, before glancing at them and adding awkwardly, “Oh, oops, except you.”) It’s interesting, the way the comic moves between these two eye shapes without settling on one or the other.

A caveat before I get into the weeds here: my reading of CALIFORNIA takes an Asian Americanist and disability studies approach, but I distinctly don’t want to say that the comicis “about” Asian Americans or “about” sick/disabled/depressed people. I’m wary of falling into the trap of aboutness, of foreclosing all the mobile gestures of this work by forcing it to inform on one kind of minority subject or another. As Kandice Chuh has rather scathingly observed, questions of “aboutness” manage difference by tidily partitioning it; they produce identities as subject matter, as a sorting mechanism of relevance for readers short on time. For Chuh, the thin representational logic of “aboutness” blunts minority difference’s potential to demand or transform.

To take this critique seriously means investigating Asian American art differently––no longer asking what Asian American literature is about, or what is Asian American about a piece of art, or marking its relevance by its supposed subject matter or authorship. For this essay, I want to try to open things up by asking what this work does with (and to) representational methods––all its diagrams, scribbles, mosaic-esque page designs. What do we learn about cartooning and abstraction from what happens to it in this comic? And what do these representational processes have to do with bodily transformation, impairment, sub-division?

I keep thinking about the wormy, stretched-out human figure trapped inside the unicorn in the dress on the cover. Stuck, or maybe straining––like a surreal parody of the “born in the wrong body” story of transness. I keep thinking back to the trapped body’s hairs, or rather their cilia––those vibrating, hair-like organelles that can do sensory, propulsive, cleaning, or signaling work for a cell/organism.

Cilia comes straight from the Latin cilium, for “eyelash,” and has also been used as an ornithological term for the “fringe” of hooked filaments on a feather. Looking closer, most of the marks here fit this type: the hairy, pipe-cleaner fringe repeats throughout the frock, face, and lettering of the cover.

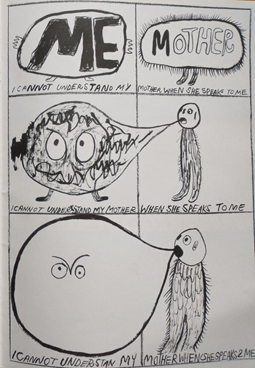

There’s some relationship happening between these prickly cilia marks and the owlish transformation that this character undergoes. And some relationship, visually, between the hairy “cilia” lines introduced in the cover and the heavy abstraction that happens in the comic itself, where lines stop acting as “mere” detail––adding and specifying information––and start messing with the stability of visual representation. At a particularly intense moment, the scribbly amoeba figures representing the protagonist and their mom become indistinguishable from hairy, blobby speech bubbles.

What results is a weirdly maximalist, weirdly visceral flavor of abstraction, where abstraction ends up looking like a collection of parts, not a clean or compressed whole. A bundle of sticks in place of a stick figure. Henriksson abstracts human and nonhuman forms to the eyelash, the barb, the fringe––not the features that biologically distinguish one form of life from another, but the shared features that link an owl to a human to a single-celled paramecium across biological kingdoms and scales.

Scott McCloud once described cartooning as a process of “amplification through simplification,” in which abstractions like the smiley face serve to focus our attention on vital features by stripping away distracting details. The cognitive work of identifying four lines as a face is somehow comforting, McCloud claims, since fewer unique features make for a more capacious and universal identification with the image. This is hardly always comforting—Sianne Ngai reminds us that the smiley was designed in 1963 “to improve customer service and employee cooperation for the State Mutual Life Assurance Company of America after a series of disorienting mergers and takeovers,” and its potentially soothing uniformity also “always confronts us with an image of an eerily abstracted being.” Ngai identifies that eeriness as the visceral reminder of capitalism’s alienated, “asocial sociality,” under which all of us unknowingly perform the abstract labor of making value real by circulating commodities. To get at abstract things like labor itself, you have to use the visceral image; to get at the visceral, you need instantly recognizable abstractions like the de-individualized cartoon face.

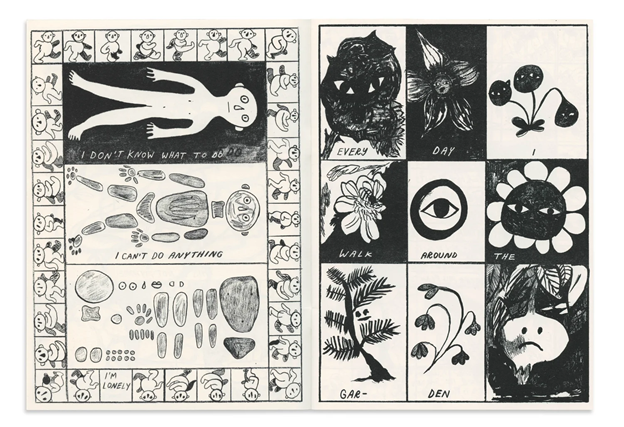

Or so Ngai says. But what about when cartooning renders a body unrecognizable, removes our ability to identify it as itself or as anything? In Henriksson’s CALIFORNIA, we get our share of recognizable frowny faces, but we also see the nearly featureless protagonist––the body that could be anybody––get chopped up as soon as they appear on the page. (Cartooned to pieces!) We don’t know what relation this figure has to the drawing on the cover, with all its particularities, because they are immediately rendered down to a collection of lumps.

If race were only a type of particularity, it too would be impossible to read in this body. But maybe it has much more to do with abstraction, which is, after all, the process of deciding which details are essential characteristics and which are merely details. “I don’t know what to do,” says this body as it subdivides into featureless shapes and misplaced features. “I can’t do anything. I’m lonely.”

Both Asian American criticism and crip theory have thought a lot about the relationship between the body as a “whole” and as an assemblage of parts. In her book The Exquisite Corpse of Asian America, Rachel Lee raises the question of why, while scholarship locates race in law/politics/economics and not biology, “Asian American artists, authors, and performers keep scrutinizing their body parts.” Lee observes that when such art (echoing the provocative anatomical exhibits of Body Worlds) emphasizes “corporality as divisible and biology as plastic and manipulatable,” critics respond by trying to rhetorically return “the extracted body part to the violated racialized whole.” Like the discourse of “aboutness,” this instinct serves as a way of managing difference and discomfort––and in this case, abstraction. Where bodily wholeness gets violated, we try our best to reconnect body parts to the story and scale of a human being.

But the imagined “original” body that you would like to restore is just another version of what disability scholar Alison Kafer calls the “curative imaginary”––an ideology characterized by a compulsory relationship to medical intervention. Or, as Eli Clare puts it: the goal of cure is “to ultimately ensure that the trouble no longer exists as if it had never existed in the first place.” (Emphasis mine.)

Henriksson’s hairy cartooning registers an aesthetic relationship between the visceral and the abstract, both of which deal in crude and elemental stuff. This linking of apparent opposites usefully allows us some distance from the idea of abstraction as untroubled, clean, and intangible and lets us linger in the unresolved trouble of cartooned biology. CALIFORNIA opens with a body in pain (and in parts); it ends with the main character’s flight not only from their mother’s garden, but from human identity. On one of the final pages, the sentence “Slowly / I / forget / I / was / ever / human,” is divided across an otherwise empty nine-panel grid. For someone like McCloud, this represents the ultimate abstraction: language in place of visual iconography! But I want to contest that argument by emphasizing the link Henriksson makes between abstraction and division. A collection of discomposed body parts, textural details, or hairy lines is not “less abstract” than the text-only page. These sometimes shaky or scratchy lines are haptic marks, nerves drawn straight onto the page. This sensitized mark-making is an interesting contrast to how Asian biology has sometimes been pictured: as inexpressive, indifferent to suffering, an “absence of nerves.”

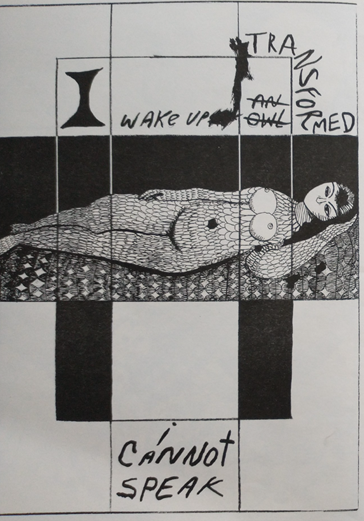

Henriksson not only scrutinizes the body in parts, but shows us what might come next for the divided/stuck/useless being. After pricking their body with the collected feather-barbs and Animorph-ing into a barn owl, the narrator wakes up as though from a dream: “I / WAKE UP / AN OWL / TRANSFORMED. / i cannot speak.” This page is both a sequence––a collection of temporal parts––and a single image: a reclining figure drawn with breasts and scaly-feathery skin.

Henriksson overlays an inset panel on top of a nine-panel grid, and the resulting matrix of lines divide our protagonist’s owlish, post-transformation body into pieces. Its seemingly lower degree of abstraction is thus literally undercut by the high-concept page design, which echoes the divided body parts from earlier in the comic.

CALIFORNIA’s ending makes a much more complicated gesture than “cure.” Its open-endedness and its melancholy trade-off (the protagonist can no longer understand language, forgets their human past) envision an intervention that isn’t about cure or the eradication of pain/trouble. I’m interested in this kind of release: “reading not to hold on, but to let go,” as my teacher Anjali Arondekar has said. I’m sitting with it still.

Works Cited:

Clare, Eli. Brilliant Imperfection: Grappling With Cure. Durham: Duke University Press, 2017.

Kafer, Alison. Feminist, Queer, Crip. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

Lee, Rachel. The Exquisite Corpse of Asian America: Biopolitics, Biosociality, and Posthuman Ecologies. New York: NYU Press, 2014.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: HarperPerennial, 1994.

Ngai, Sianne. “Visceral Abstractions.” GLQ 21, no. 1 (January 2015): 33-63.

Smith, Arthur Henderson. Chinese characteristics. Fifth edition. New York: Fleming H. Revell, 1894.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply