The history of comics is a noisy one. It’s written in a million punches, pratfalls, and exclamation points. I went to my bookshelf for reference, the first I found was From Aargh! To Zap!: Harvey Kurtzman’s Visual History of Comics. Two sound effects in the title! It never struck me before, because it’s so natural to throw in a “blam!” or “biff!” when writing about comics.

Comics are silent.

Most cartoonists have viewed this silence as a challenge to overcome. Loud sells, and those who’ve made a living drawing pictures have found their own selling points, whether through dynamic action…

…frenetic acting and line work…

…or an indulgent use of text.

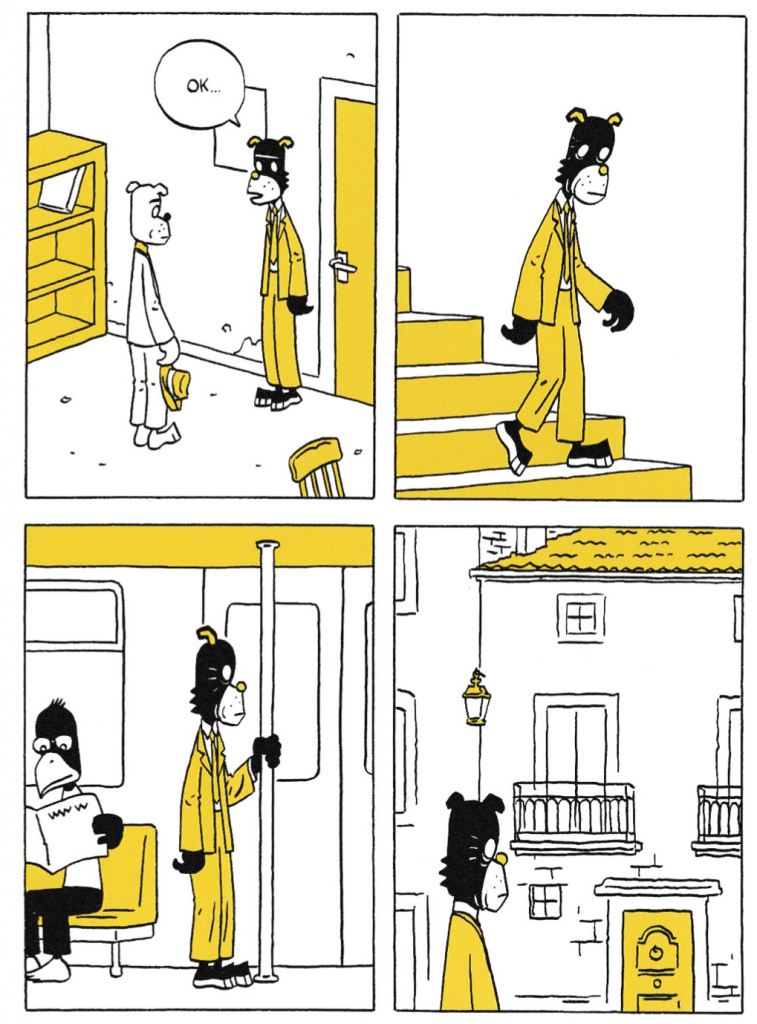

But in recent decades, the silence has crept in. This quiet procession is led by Norwegian cartoonist Jason with comics as still and ominous as a glacier. The silence fills Jason’s work so fully, that I can flip to any page of any book and find a perfect example.

Jason does us a huge favor in deciphering the influences on his style by making them characters in his stories. The stripped-down storytelling of Ernest Hemmingway, the whispering lyricality of Leonard Cohen, and the deadpan stare of Buster Keaton, the unanswerable riddles of Magritte… all of these speak to Jason’s desire to create a body of work that explores the enigma of the unsaid.

How does Jason go about achieving this? The first level is his technique. At every opportunity, Jason restricts his choices to only what’s necessary.

When you first see a Jason drawing, his use of a clear line stands out. He’s part of a long tradition here, but also apart. While Herge or Chris Ware’s steady unweighted lines showcase intricate worlds, Jason’s line is thicker, making such detail impossible. This forces every background to be stripped down and abstracted, like a white noise over all his work.

***

Though he’s experimented with other formats, most Jason books have 4 panels per page. This limitation created a steady rhythm. Every page becomes a little meditation, like a Peanuts strip but with more murders.

The regularity of Jason’s composition creates an otherworldly stillness. Every doorway right angles, every street and bar counter is 30 degrees. This crystalline repetition goes on page after page, book after book, so that the whole of his work lands as softly as Christmas snow.

Even Jason’s character designs add to our internal silence. The most obvious aspect is the use of animals. Normally, when we see a person, our mind automatically makes a series of judgments about them: where they’re from, how we expect them to act, whether we like them. But this doesn’t happen when we see a crow or a bear. Jason deepens that silence with his characters’ interchangeability. They all have the same build, head shape, arrow-straight posture, and vacant eyes. When you look at a Jason character, your mind makes no assumptions and asks no questions.

Jason’s characterization is as anonymous as his designs. His heroes invariably live in the same apartments with the same lamps, couches, and bookshelves. The same baren tree is seen out of their windows as they make the same simple dinners at the same stoves. I’ve read every Jason book at least three times, and couldn’t tell you the name or traits of any of his characters.

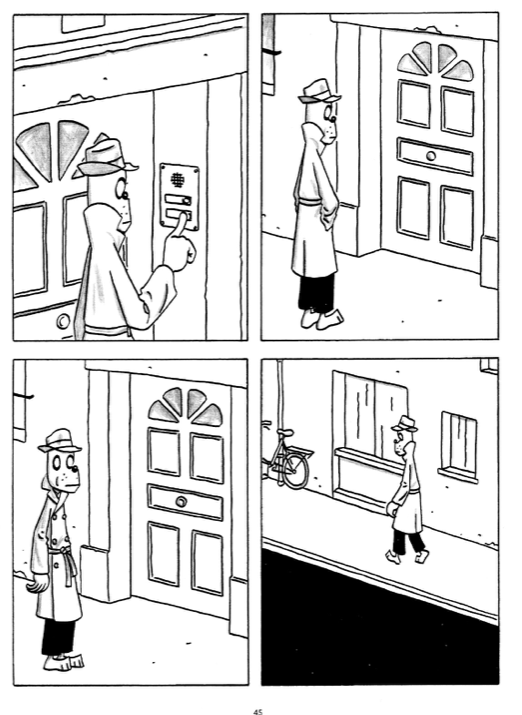

Once they leave their apartments, Jason characters never seem to touch the world. One would never imagine their footsteps making a sound as they walk, always mid-step and weightless. Jason presents the idea of walking rather than illustrating the act itself. One of Jason’s biggest influences seems to be road X-ing signs.

This acting quirk of Jason’s becomes more evident in dramatic moments. Consider this panel from Lost Cat.

Most cartoonists would handle this scene with some expressive flourish, but Jason draws it no differently than he would a character cooking ramen. The money hangs in the air. All action is suspended. You could imagine this as a sign in a library quietly reminding you to throw cash here.

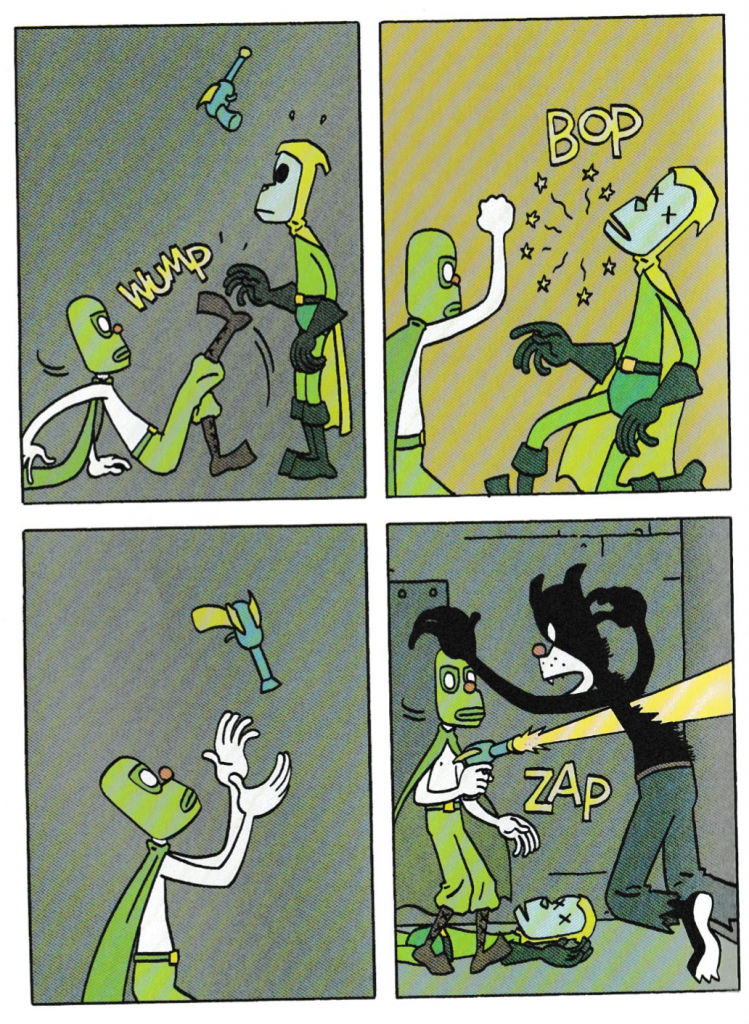

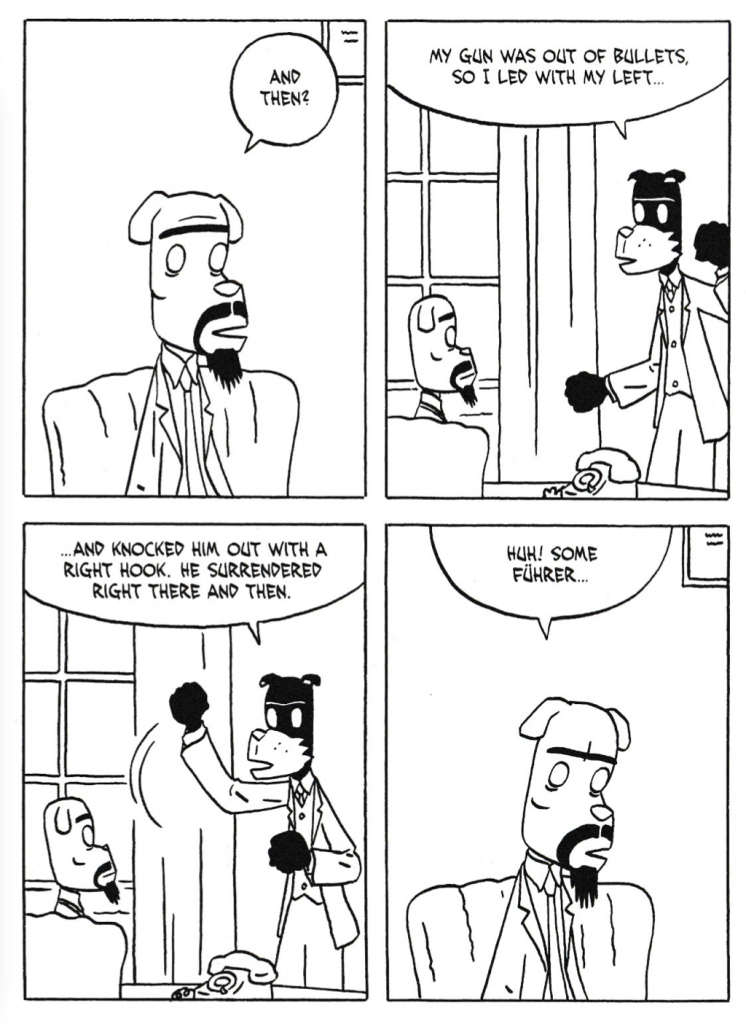

When Jason does employ action, it’s usually with a layer of irony. He uses the comic language of noise, but muffles it. Look at how he handles this fight sequence.

Both the context and content tell you this is a cartoonishly violent scene, but in Jason’s hand the kicks and punches land with a feather touch; signifying rather than expressing “caution: violence at play.”

To be clear, there is a lot of action in Jason’s stories. They’re full of pirates, time-traveling assassins, monsters, heists, and alien invasions. But the action is never dominant. Rather, it provides the space for the silence to exist. In the quiet of Jason’s action, the characters are allowed to exist in a kind of alienated intimacy.

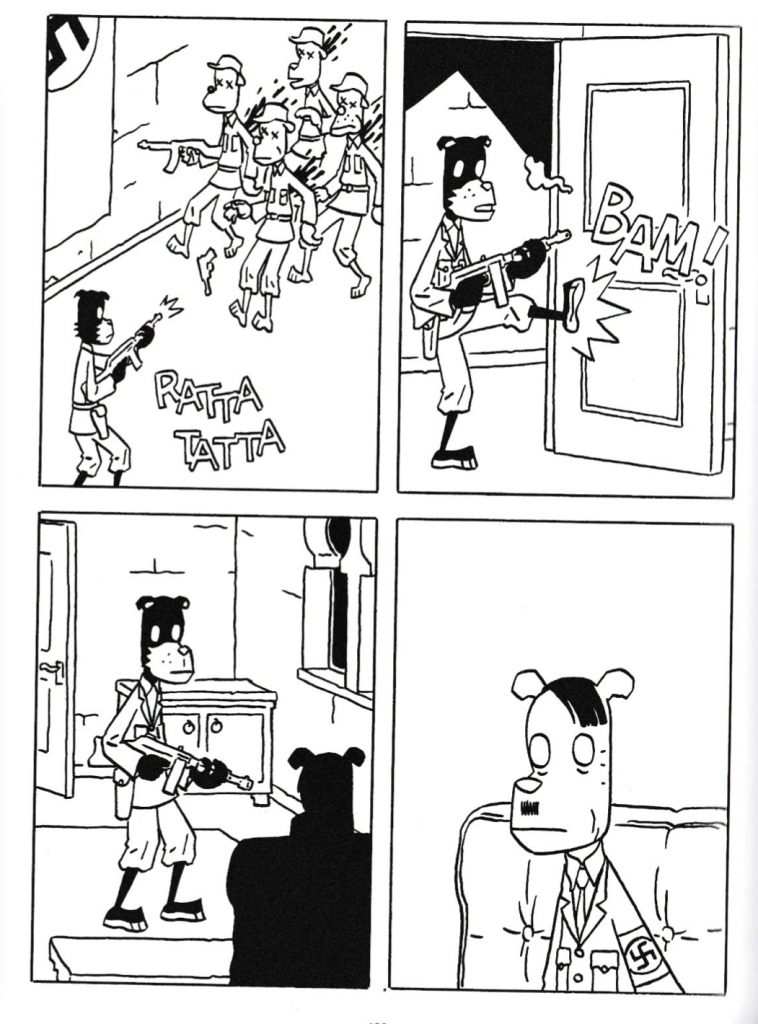

Nowhere does silence structure Jason’s work more than in his latest book Good Night, Hem. Here, a fictionalized Ernest Hemingway leads a group of commandos on a suicide mission to kill Adolf Hitler. Let’s look at the climax…

In the countless comics about ragtag groups on a mission to kill Hitler, this is probably the only one to cut out right before the big bang. The effect is striking. The aftermath is filled with a quiet louder than any gunshot or punch. There’s no victory party or snappy one-liners. Defeating Hitler is just a thing he did. Here Jason’s comics illustrate a truth; life isn’t the noise of our biggest moments, but the long silences after.

So, Jason is a quiet guy. Why does this matter? I think that the absolute silence of Jason hits on something crucial in the medium. In Milan Kundera’s the Art of the Novel, he suggests, “the novel’s sole raison d’être is to say what only the novel can say.” The same could be said for the graphic novel. In charting its course as an emerging art form, literary comics do well to note this strength. In the loud, nagging media environment we find ourselves; comics can be a sanctuary of quiet thoughtfulness, a place to reflect on our quiet unease rather than escape it.

I could say more, but I think I’ll let Jason have the last word…

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply