Job was a god-fearing man, loved and loving, fair and friendly, whose only real flaw was his lack thereof, setting him square in the middle of the Devil’s theological shooting target; when the Devil came to God with a bet, thinking that Job’s faith and kindness would snap at a time of crisis, God took the bet, foisting troubles on Job, whose back proved sturdy enough to carry his suffering and his faith, ultimately allowing him to be rewarded, his suffering not forgotten but amended by the Heavens. Sisyphus, unlike him, was too smart for his own good, thinking in his hubris that the Gods can be bested, and after one triumph too many was punished, thrusted into a situation from which there can be no escape, even with the strength and wits of a thousand Sisyphi.

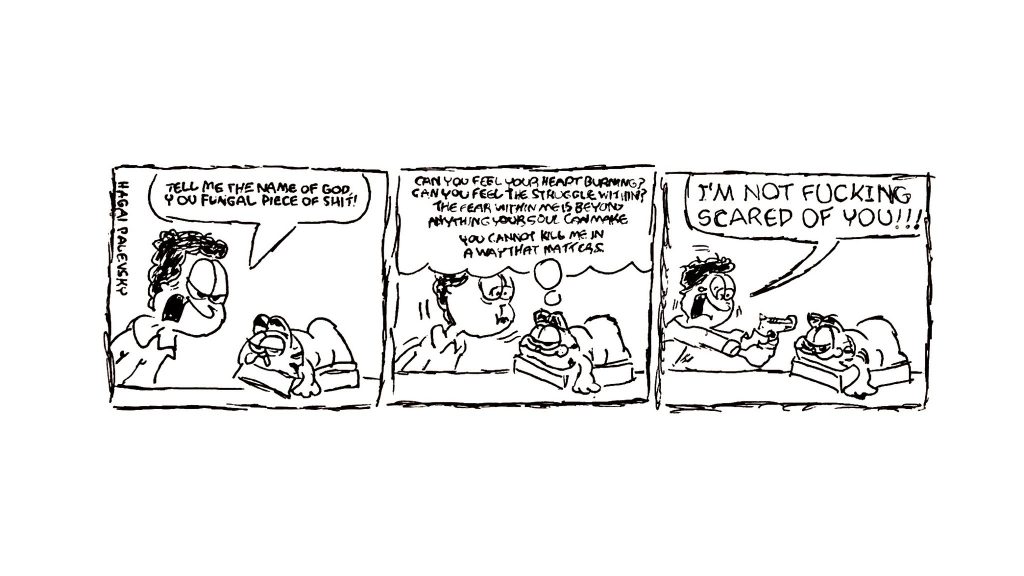

There come times, however, when a man has the positive qualities of neither Job nor Sisyphus, yet suffers the punishment of both, a punishment both handed and enforced by a totalitarian all-knowing and apathetic ruler whose fur is orange, whose name is Garfield, and whose allegiances, even after 45 years of ink-on-paper existence, are unclear at best. This is the premise of the Jim Davis comic strip Garfield.

The man in question is a cartoonist, although what sort of comics he makes is after all this time still a mystery; while many have assumed, given that this Jon Arbuckle fellow is partially based on Jim Davis, that his comics are, in fact, the comic strip Garfield, but this has never been confirmed. I would say, as I have in the past, that I doubt that a cartoonist would so thoroughly humiliate himself and portray himself in such a laughably negative light, but I realize that this is the basis of an entire genre of comics by American male cartoonists. What we do know about Jon’s comics is that at least some of them feature a red stick-figure person and that, while some of them are strip formats, others sport the page structure of a traditional comic book, yet all other aspects remain a mystery.

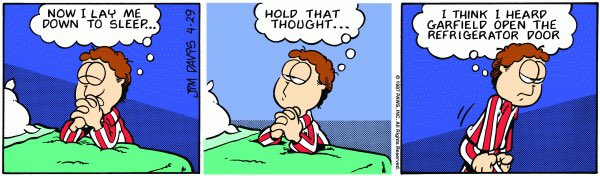

One detail that has briefly been mentioned yet unaddressed about Jon’s life, though, is his apparent religious beliefs: on April 29th, 1987, a strip was published showing Jon on his knees, hands clasped together, thinking a thought that starts with “Now I lay me down to sleep”—and is truncated because Jon thinks he heard Garfield opening the refrigerator door. “Now I lay me down to sleep,” of course, is a children’s bedtime prayer from the 18th Century. Jon can be seen here as immature, employing tools of worship composed with children in mind, but also—if one is more generous in one’s judgment—as accepting of Christ’s commandments on a very literal level: truly, he lives up to Luke 18:17, and he will surely enter the Kingdom of Heaven as he receives it, “as a little child.”

Or he would have, if not for the furry obstacle in the kitchen. Garfield himself has rejected any higher power, and, within the moral-theological realm of the Arbuckle house in Muncie, Indiana, he is right to do so—he is the highest power, the Alpha and the Omega, and he has committed himself to ardent worship only in the earthly realm of the refrigerator. This, then, is the theological function of the Garf: he is the bet on Job’s fate, he is the rock that keeps rolling downhill no matter how many times Sisyphus rolls it up—Garfield is a feline trial of faith, and, to those who fail, a one-cat inquisition.

Given the mention of Jon’s faith as anecdotal and the display of Garfield’s mistreatment of his owner as systematic, one wonders about the fortitude and habits of Jon’s faith. After all, he seems to be content, and, above all, he seems to be calm—the calm you would associate with submission to a higher power, with faith in a divine plan. No anger seems to last, neither does it ever bubble up; grudges are never held past the third panel.

Yet something is terribly amiss in the moral premise of faith, at least as it applies to Jon Arbuckle. Much of religious narrative (especially in Judaism and Christianity) makes the connection between worship and morality, the “righteous man” being a concept that extends to both the moral and religious realms (the religious itself being, as it appears in the text, a set of moral imperatives, and does not end at faith in demiurge and savior). But, though the moral-as-divine was baked into religious living from the get-go, it has been reframed to mean “moral faith can only have one form, and it is the form the hegemon believes in,” and very often that form of faith has no moral value at all, or at least its value is entirely different from the way it perceives itself (one need only look at current-day Evangelical Christianity and take a fleeting glance at the New Testament to understand that these are two completely different religions). All of which is to say, evidently, a faith in God does not make one inherently moral, inherently righteous; it just so happens that narrative depictions of such righteousness extend to both fields of life.

Jon Arbuckle, though, presents an extreme version of a more realistic depiction of faith, in that his faith has absolutely no bearing on his morality and is entirely limited to his model of worship, which takes place in his bedroom, for no one but the Good Lord and the terrible cat to witness, and is only mentioned once and then is cast aside. Like most modern-day believers, Jon does not see a belief in God as having any moral requirements; he is entirely neutral, ardently refusing to commit to any side or to make himself righteous through action. Any good intentions he might harbor are so fumbled by his terminal nothingness; he is a moral void of a man—and for this, of course, he is punished.

Let us return, then, to the punishment and the entity carrying it out. As mentioned earlier, a key feature of Garfield’s command of form is its extreme employment of the self-contained strip. There are no longer arcs of significance, as in Peanuts; there are no echoes or riffs on previous strips, as in Heathcliff; in Jon Arbuckle’s world, everything that cannot be said in three panels, or in nine panels on a Sunday, is not worth saying. If there is a continuity in Garfield, it is a dim one indeed, expressed only in the appearance of new characters or the disappearance of old ones. There is no reference to the outside world, either—Jim Davis has gone on record as “consciously staying away from the political,” instead choosing to focus on the funny and the simple. The result is an eerily desolate, narrow world, which seems to revolve around this mediocre guy who might be well-intentioned but, in practice, is kind of an ass who cares not a single bit about the world outside his house, a king of the Dunning-Kruger effect and, the second his cat enters the scene, a nuclear shadow of his own self—and Garfield, my friends, is the Bomb.

Garfield’s deeds, when isolated to one strip at a time, would constitute hardly anything more than “mischief,” or explained away by our lack of feline behavioral understanding; the cat is id-driven and bored, but hardly more than that. In aggregate, though, it’s far more than idle mischief—there is an almost cosmic hostility in Garfield’s treatment of Jon. Jon, being so self-centered and so terminally unaware of the world around him, has, by the power of his own mind, managed to effectively shrink it down into such a small experience—and for such a fit of hubris there is only one punishment. Garfield interrupts Jon’s worship, then, not simply because he’s a cat and he’s hungry and bored, but because he has seen Jon’s worship, in word and in action—and it is not enough, it is utterly unworthy.

Ultimately, Jon will wind up winning this battle, the same way he wins all others: by being so blissfully, terminally narrow-minded that he renders Garfield’s punitive measurements futile, bereft of any longstanding effect. It is true that Garfield is the Bomb—but in this dialectical battle Jon is a cockroach.

It is comparable, in a perverse way, to the story of Abraham’s binding of Isaac, as interpreted by Kierkegaard. In Fear and Trembling, Kierkegaard breaks down the binding of Isaac in detail, reaching an understanding that, ultimately, the reason Abraham was so willing to sacrifice his child was not because he was such a terrible human being that he is willing to kill a kid, but because he was so dedicated to his faith that he knew that a benevolent God would not condone suffering. Abraham, Kierkegaard declared, knew that God is so loving that he would, in one way or another, give Isaac back to him after he has proven his faith, which is why he was so ready to commit the ultimate sin in pursuit of holiness.

Where Abraham and Jon diverge, however, is in their intent and purity; Kierkegaard diagnosed Abraham’s actions as a teleological suspension of the ethical—the enacting of an ostensibly-unethical deed in the knowledge that it will fulfill a higher ethical objective, keeping the end-point at an unquestionable moral positive. In Abraham’s case, this ethical objective is the worship of God—but what would such a purpose be for Jon Arbuckle? Further examination would see that there is none such objective; Jon’s actions might not be as textually extreme as the killing of his own son, but neither are his intentions as valiant as Abraham’s. No, if Jon’s actions are a teleological suspension of the ethical, the telos is not the worship of God, but the worship of himself alone—and that is hardly a calling worth pursuing.

Camus famously broke down the myth of Sisyphus arriving at the conclusion that, in his post-mortem fate, Sisyphus remained a hero in his victory over the absurd because he is aware of his absurd fate; he manages to find meaning and purpose in his struggle, and he keeps rolling his rock uphill with a clear mind, with full awareness. Jon, however, is hardly aware of his absurd fate; it is one that he constructed himself fully subconsciously. The end-point, however, is the same: he sees himself as a hero and considers himself fulfilled.

What, then, are we to make of Jon Arbuckle? Is he a blueprint for ideal existence or a cautionary tale? Is he to be embraced or avoided? Is his suffering justified by his dubious morals? Questions pile up, and answers are much harder to find. This much, however, is clear: Jon Arbuckle’s world is as narrow as the space between two of the panels that make up his life—and, to him, that space is as wide as all of God’s creation. His self-centeredness is so powerful, so precise in its focus, that it manages to disarm and overcome anything and anyone that might attempt to foil it. In Jon’s inevitable 264-page autobiographical graphic novel, he would surely present himself as a good man, and he would believe in this idea, as much as he would believe in his peace. Through the peace given unto God’s believers, Jon Arbuckle is truly content, and, in this, one wishes momentarily that one were more like Jon—yet, when one examines Jon’s actions, they see that, if this is what a content and righteous man looks like, then perhaps it is better to stay miserable.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply