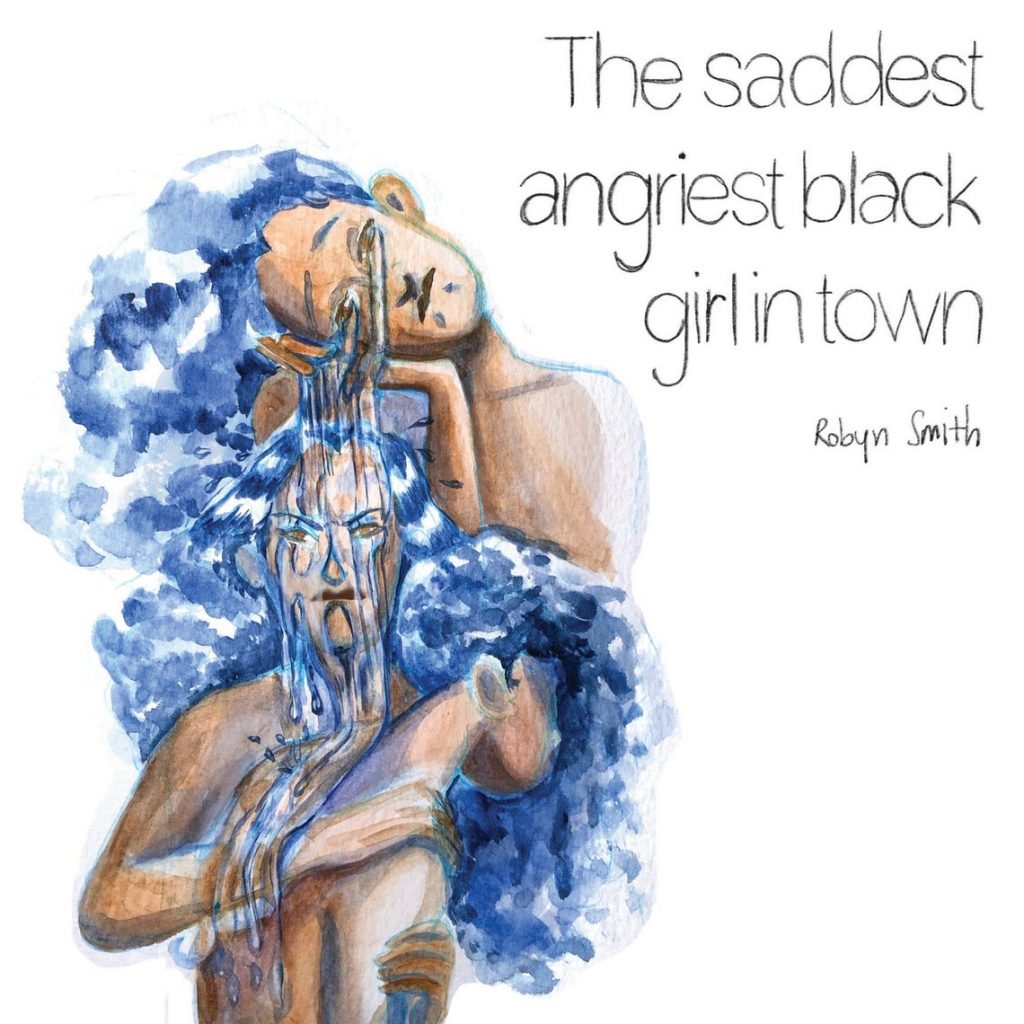

The cover of The Saddest Angriest Black Girl in Town is a curious, expressive one: three brown-skinned women stand connected. One crying, her tears flowing creating a mask for the young woman beneath her who is wearing an angry look, her eyes narrowed. She’s holding the third young woman whose face is turned away, her body language hinting that she’s disconnected, unavailable, inaccessible. These three representations serve as muses giving the reader a taste of the content of each chapter of this short autobiographical work in comic form.

Created in 2016 by cartoonist Robyn Smith, the book recounts her experience being one of the only Black people in a rural Vermont town and how that time affected her mental health and her grasp of how Blackness is viewed in the world. On the surface, this is an auto-bio comic that explores the intersection of Blackness and mental health. Reading through the pages reveals an illuminating piece of what it meant to be Black and woman and exist in a place where she found herself not always wanted, respected, or valued. Smith’s The Saddest Angriest Black Girl in Town, hit home for me, especially given current events in recent years.

Originally published to great fanfare in 2016, this comic sat previously out of print until it was picked up by a new publisher, Black Josei Press, and received a new print run in 2021. This reprint allows a new audience to read about a Black artist detailing the pressures and tensions of being Black and woman in a mostly white space. Smith’s work delves into what it looks like to navigate such a place, the illusion of safety, and the exhausting toll of her mental health. After reading it, I couldn’t help but be stunned by how timely this comic became and remains so in 2021 in the awful aftermath of surviving 2020.

In conversations and discourse online and offline, the action of taking up space has been talked about and debated to the hills. To take up space can be defined differently for everyone and anyone: whether it means physically standing or being present somewhere like an office building, classroom, or courthouse. Or perhaps being able to offer your opinion or explain your feelings in paragraph form in a discord server–taking up space may not always even be sometimes we’re even always conscious of. Yet, for some of us, marginalized people may always have this on the brain as it is certainly linked to agency. In the early pages of the comic, Smith presents herself on the page once feeling unapologetic in her skin. Then she finds herself self-conscious: pulling up her natural curls with a hair tie when out on a walk, hanging out with non-Black friends asking if she talks about “Black stuff too much”.

She goes from “I was so apologetic. I once carried myself like this everyday” to “ I upset a sort of white peace and I can’t help but feel sorry for making you uncomfortable”. From the curls on her head to the soles of her feet, she reached a place of insecurity and unsure footing as she moved from one location to another. Everything was up for debate, up for interpretation, for doubt. Outside this newer edition’s cover, Smith’s artwork is without color, her drawings created by pencils in a black and white tale. This feels intentional: the work has a pared-down look which works with the range of emotions present. In the last few pages of this first chapter, the author mentions her anxiety and her inability to even sit down with her thoughts undisturbed. It leaves her a scalded mess. I can think of countless times where I, too, felt like my cup had spilled over, like I had disturbed the “peace” I had tried to upkeep for the sake of others.

There are pages of Smith sitting looking at the work of others making jokes or making their stance known on one of the biggest rallying words of this era, this generation of activists: “Black Lives Matter”. She sits outdoors and sees a van with a back window’s sign with the words “Black Lies Matter” plain as day. At work in what appears to be a deli or bakery, a white coworker sees a tub of black matting and laughs in front of Smith before using a marker and writing “Lives” between the words on the container. How could such a meaningful phrase be twisted into what it is not? How could others reduce it to a good laugh at her expense? Smith elaborates on her confidence dwindling as she finds that she doesn’t feel her life matters as much to those around her.

Those pages call to mind a situation last year while walking to stand in line to pay for groceries. I was startled by a man, a total stranger to me who stomped around me angrily, upon him noticing my Black Lives Matter face mask. I haven’t worn it since. It was the same week I noticed the Trump flag in a yard of a neighbor a five-minute walk away from where I live. Safety is a luxury not afforded to all of us. Thread these feelings to how I think of Breyonna Taylor so often and continue to do so and the sisterhood of Black girls and women joined in death at the hands of the police. Breyonna was killed in her home, one of the safest places one would think.

She lost her life at home, away from schools and workplaces where instances of violence big and small from microaggressions to assault happen for so many Black women. I thought of protesters around the globe in the streets protesting a number of issues from government corruption to health concerns–and the many united marching for Black lives. I grew troubled, triggered by the violence pressed on their bodies by those who we’ve all been taught are there to protect us. I often think too long and too much about how unsafe the world feels for me almost on a daily basis.

At the start of the second chapter, there’s a page devoid of any artwork. Just these words: “When I think about how Black I am, I become angry. Not because of my own Blackness but because of how aware of it I’ve always had to be.” It is perhaps one of the bravest lines that I have even read on a page, let alone in a comic. It is a strikingly honest declaration. The words speak to the almost second-hand citizenship that so many Black folks feel ingrained in their national identity here in this country. Against the white page, those words in Smith’s handwriting look like scripture, like an old diary or notebook you had in your younger years that reminds you of a truth you had once forgotten. Smith goes on to feature pages of her crossing the street and sitting in a classroom being watched. Pages of her being approached in and for conversations that veer off the beaten (fetished) path about her glowing skin and her homeplace of Jamaica.

Perhaps the most expressive pages are her recounting the times she heard the n-word and the rage and ultimately defeat she had to manage internally in her time living there. A single page sees her outdoors, sitting on a sidewalk, pressed into a building, head cradled by her arms with the words “I feel so small”. On that page, she looks so small, so utterly alone. Smith’s comic is a brilliant, illustrative example of how autobiographical comics work and how they can reach readers in a medium that is so often dismissed. Reading this brings to mind the first time I read Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis back as a student in high school. Being a graphic novel, Satrapi’s work here in the States was often waved off as not being serious reading or worthy of being in classrooms at first.

I remember being blown away by the entry point into her world: her feelings about the war, how her gender was perceived, and how her identity was changing. Auto-bio comics work and work well when creatives are allowed to tell the stories they want, no need to tell the world. No matter how awkward, saddening and true. The Saddest Angriest Black Girl in Town stuns me and continues to do so because of Smith’s range to break down the many ways she existed in this place where she often felt so small. Seeing her account of the ride on the struggle bus she had a seat on mirrored not only my own lived experiences but artfully elaborated on the problems that continue to plague Black folks today.

I’ve always felt drawn to autobiographical comics as they tend to be of personal experiences shaped by the world we live in. Even if I shared nothing in common or very little with the creator, I always felt grateful to read comics that carried much weight. Over the years, I’ve read a number of comics in this genre that make me elated to know that storytelling is still one of the greatest tools in the world. Autobio comics make me remember that stories still matter and that people will continue to make them. The Saddest Angriest Black Girl in Town carries that weight in the way that a fellow black girl knows and sees, leading me to feel seen and acknowledged in the days of Black Lives Matter.

The Saddest Angriest Black Girl in Town allows me to feel seen and acknowledged in recovering from Trump’s hold on this America and in the sometimes bleak and dark days of now. I don’t and can’t always give voice to what I endure: I can’t always share the rage and sorrows that come with existing in this skin that is both non-white and female. Yet, having this comic exist in my hands to read is a bigger comfort on the days when the noise is too loud, the siren won’t stop, and the world makes me feel like this Black skin is more detrimental than a blessing.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply