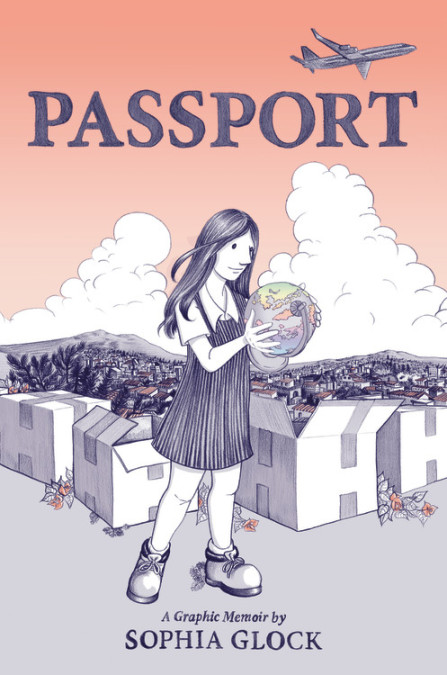

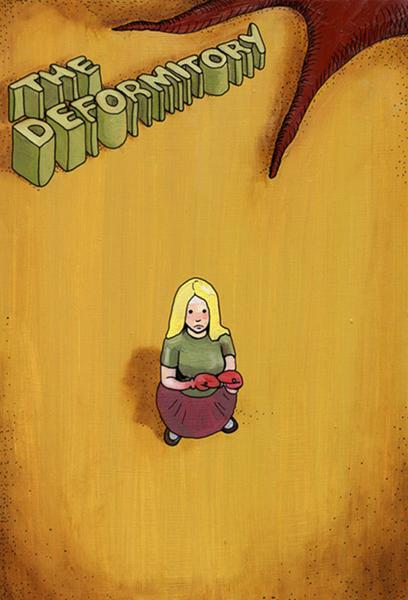

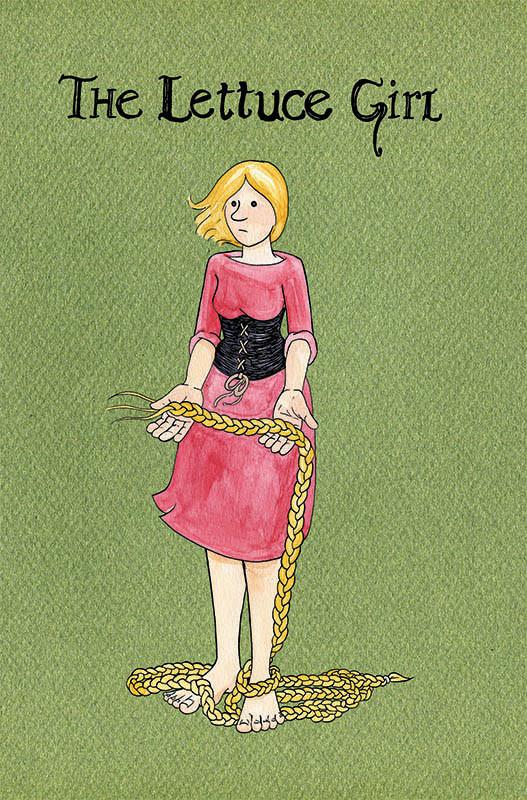

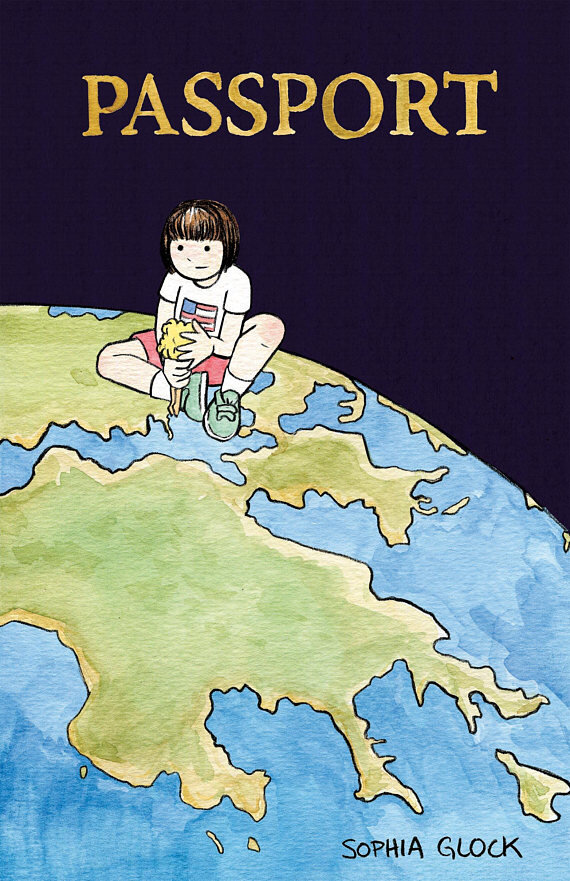

Sophia Glock has been writing about the experience of being both a parent and a child for as long she’s been drawing comics. She’s also been drawn to the narratives of the outsider, the loner, and the weirdo. Her comics have always been frank about sex and its consequences. However, up until her debut graphic memoir Passport (Little, Brown Books), they’ve always been fantasy comics. Her Xeric Grant-awarded comic, The Deformitory, was about a girl at a very unusual school for unusual people. Her miniseries The Lettuce Girl added a modern spin to the tale of Rapunzel, putting a lot of bad parental figures in the mix.

Glock’s storytelling started out as scratchy and visceral, but she’s smoothed off the rough edges of her line to craft something polished but still visually stark. Though Passport is aimed at a Young Adult audience in terms of format, Glock doesn’t seem to hold back much in her memoir of being a teen living in an unnamed Central American city, feeling trapped and isolated. This was until one day that she inadvertently discovered that her parents were not what they seemed. In fact, they worked from the CIA, a discovery that pushed Glock into creating her own double life.

Passport is richly nuanced in its depiction of everyone, from some of the strange people she befriended to her parents and the rest of her family, but it is most especially nuanced in its depiction of herself. She’s not a hero so much as she’s a human trying to blunder through, creating her own self when her old one no longer seemed to suit her.

I recently had the opportunity to talk with Sophia Glock. In this interview, she discusses her career, her influences, and how things have changed since she became a mother.

Rob Clough: You’ve said in the past that something clicked with you when you were around 12 and were obsessed with the X-Men, that you realized comics were what you wanted to do. What era of X-Men was this?

Sophia Glock: This would have been 1996. I’d been very into the X-Men cartoon and so when I saw a Rogue comic book, a mini-series written by Howard Mackie which I found at a flea market of all places, I bought it. Honestly, the series doesn’t hold up for me now, but at the time I was very much in love. It was all over after that. Or at least that is the story I tell myself. It’s easy to see the path we take as obvious as we look behind us, but I’m not exaggerating when I say that at the time that comics felt like a calling.

RC: What about the X-Men drew you to them? Did you see yourself as a similar kind of outsider looking for acceptance, or as someone alienated from “normal” culture? Who were your favorite characters?

SG: I think the fundamental concept and paradoxes of the X-Men have a special appeal to adolescents. Nothing is quite so teenage as that brand of angst that X-Men specializes in: you’re a freak, but you’re also beyond powerful. The world doesn’t (can’t!) understand you, yet you are compelled to protect the bigots from themselves. So yes, like a lot of teenagers I felt very different. I did not feel as if I belonged and I was right, I didn’t belong. Specifically, I was obsessed with Rogue. Her character is the perfect metaphor for a teenage girl who is both desperate for, and terrified of, sex. Gambit was a close second.

RC: What were your earliest comics stories like? Were you drawing superheroes?

SG: Oh dear, sometimes. I would create these tortured, derivative superheroes and villains, but they never made it beyond character design. By the time I started composing panels in sequence, they were much more conceptual (probably due to my having discovered Chris Ware in The New Yorker). I used to write these three-panel strips featuring a character I called Nikon, a reference to the camera brand and the idea of capturing moments of time. I’m cringing very hard right now at how very clever I thought I was.

RC: In a scene in Passport, your mom refers to an issue of Gen13 you were reading as “trash.” Did she generally think this way about your reading comics? Did anyone else in your family read or draw them?

SG: My mother was (rightfully) repelled by some of the comics I was bringing home and worried about what messages they were sending about women and women’s bodies. But yeah, even though we all read the Sunday funnies, clipped New Yorker gags, and that trade reprints of Calvin and Hobbes and Far Side were piled up at our bedsides, comics were not being taken seriously as literature in my house. My little brother Patrick is probably the family’s second greatest comics enthusiast. His collection is massive. At one point I turned over my whole pathetic superhero comics collection to him because I knew he would take good care of it.

RC: Were you still reading and drawing them avidly as you approached your junior and senior years of high school?

SG: Yes, but I was increasingly critical. I wrote a ten-page research paper my senior year titled Misogyny in Comics, largely inspired by discovering Gail Simone’s Women in Refrigerators online. I was getting very greedy for a different type of comic and increasingly suspicious of who these books were really for. I’d discovered this new breed of comics in Chris Ware, so I knew other stories were possible, but living overseas (pre-internet shopping) it was hard to find variety beyond Marvel and DC and a smattering of Manga.

RC: It’s interesting to revisit your old work and find it filled with the same sort of themes you tackled in Passport, only in a fantasy setting. How much of that process was a conscious and intentional way of working out these ideas, albeit in a fantasy setting?

SG: It was not conscious at all. I think all our lives are dominated by a few ideas that we tackle over and over again. I can no more avoid these themes than I can avoid myself.

RC: What was your comics education like at the School of Visual Arts (SVA)? Did you have any particularly inspiring teachers or classmates?

SG: I was incredibly lucky on many fronts at SVA. Their illustration MFA is not explicitly a comics program so I had to make sure I stayed responsible to my own goal and it took me a minute to figure that out since so much of the curriculum is in service to illustration. I was beyond lucky that the visual genius Dunja Jankovic was in my class. She was so far beyond me in terms of making comics, so that was inspiring, and she was maybe the first person I could talk comics with who knew what comics actually are. Up until then, many of the conversations I’d had about comics invariably devolved into some sort of quiz where I’d feel embarrassed that I had no idea who inked issue #300 of Uncanny X-Men or whatever. Dunja, being Croatian, was tapped into a whole different tradition of comics. It was wonderful.

Another stroke of luck was having Gary Panter teach my second year, which was incredibly fun, but he’s very wise, beyond being a comics legend. Most importantly though, we were allowed to choose our own personal thesis advisors working in our field of interest and I was lucky enough to land the comic artist David Heatley. Working with David was the great stroke of luck of my artistic life. He opened it up for me. He taught me how to actually make the thing. He taught me how a comic book works and it’s thanks to him that The Deformitory became what it was. I should also note Josh Bayer was in the class behind me and that was wonderful, because not only is he a wildly fantastic comic artist, but, like me, he is absolutely married to the medium. Josh was also into the comics scene in New York in a way that I had not yet managed to figure out, and he introduced me to comic artists that I would have otherwise never met, at least not then. I feel like I can trace a direct line from those introductions to much of my life in the indie circuit and people like that is what SVA gave me.

RC: The Deformitory was your first major comic, winning a Xeric Grant. How old were you when you got it? Did you feel validated as an artist when it was awarded?

SG: I was 24 years old. The Deformitory was my graduate school thesis and, yes, it was profoundly validating. I still mourn the loss of the Xeric for all current young independent cartoonists. I know they rationalized that crowdsourcing platforms had replaced the need for the Xeric grant, but the real benefit of the Xeric was not the cash, but that external authority promoting unknown artists. It was a beautiful thing and I am so grateful it existed when I needed it.

RC: One of The Deformitory’s major themes was that of alienation. Was it ever a conscious feeling to channel your own feelings of displacement and alienation growing up into a fantasy setting?

SG: I wasn’t conscious at all. The entire concept of The Deformitory came out of me mishearing someone saying “dormitory”. I sort of giggled in the moment, but the next day I had a vision of my freshman college dorm as a home for disenfranchised souls, each room housing a separate case study in anxiety, self-harm, depression, disordered eating, and sexual assault … all the things that we as teenage girls had collectively and individually dealt with during that year and others, all those girls partitioned off in separated cells of suffering. It’s only after writing story after story about isolation, alienation, and towers that I realize this is something inside of me I cannot help but explore.

RC: The Deformitory tells the tale of Delores, who had deformed hands up until one day she gets a new pair of sentient, crab-like appendages who become her friends. Later, she makes them jealous when she goes on a date and they try to kill her, and she is forced to drown them. This is a potent metaphor for desire, addiction, and self-destructive behavior. Had you been able to express these feelings that were clearly explored in Passport in your art like this prior to The Deformitory? How did your college experience change the way you perceived yourself and your upbringing?

SG: College allowed me to gain perspective on my family’s patterns and relative insularity. For example, it took suffering from panic attacks at school for me to see that my family is rife with anxiety. College was also just a great time to learn about people by having the most intense and twisted relationships possible. Which, incidentally, inspired a lot of The Deformitory. It’s very difficult for me to separate my own awareness of my feelings from the things I learn about during the writing process, but I will say that I never actually know what any of my books are about until I have written them. I try to be informed by what interests me, what piques my curiosity, as opposed to going after stories that confirm what already think I know.

RC: Your next major work was The Lettuce Girl, which was a new take on the story of Rapunzel. This story seems to be pretty explicitly about the ways in which parents are flawed human beings, which creates a relationship with their children that’s far more complex than simply “good” or “bad.” In it, a pregnant mother craves lettuce so much that she demands her husband do anything he can to get it. He steals some from someone who is presumably a witch. She demands their firstborn child in return…and it becomes clear it’s not the first time she’s done this. The girl is raised by the witch, thinking she’s her mother, but she eventually escapes into a cruel, harsh world. They eventually meet again one day with forgiveness, but their paths are no longer aligned.

This comic is filled with questionable parenting decisions, including a lifetime of lying to one’s children about who they really are. The reader is introduced to absent parents, neglectful parents, and toxic parents (with the carnivorous witch from Hansel and Gretel fattening up the girl so she can try to cook her).

How much of this comic was a way of working through your own parents’ questionable decisions? As a parent yourself, how has your view of this comic and your parents changed?

SG: The Lettuce Girl was explicitly a story about the dark side of motherhood, and, in it, I was working through a lot of my own lingering resentments over being raised with this idea that the world is inherently dangerous, that my vulnerability is a liability, that I cannot manage my own sexuality or desires, and that you can only trust family. Of course, the world is dangerous, girls and women are vulnerable, but we must empower children in order that they can navigate it. I got right with my parents years before having kids, thank goodness, and since I wrote The Lettuce Girl from a place of empathy for parents, I still stand by a lot of the ideas in that book. Having children and being a child is a dark, twisted, and complicated thing. There is no way around it.

RC: One of the things I found fascinating about Passport was your character’s journey from early pliability to resolute stubbornness. In your Passport mini, there’s a story about a very young you who is put to bed by your father. Your reaction is to ask where your mother is, but she was “busy” and your father demanded that you say good-night and “I love you”; your response was a blank stare. What led you to record this anecdote? In some ways, I saw this less about your father and more about the fierce loyalty you showed to your mother.

SG: Actually, I wrote that story for an anthology which never came to be, so I collected it in my mini Born, Not Raised. And yes, it is a reflection of how I both resented my father for being angry a lot of the time and adored my mother the source of all comfort and sweetness in my life. I actually have no memory of doing this, but it was based on an anecdote (one of many) that was constantly told to me as evidence of how difficult and stubborn I was as a kid. I think I made it into a comic almost as a “fuck you” to constantly being told that that was who I was. It was sort of like “Oh, you like this story … how does it read in black and white?” I also think it is hilarious and cute. Children are terrible. I thought my dad would laugh when I showed him but he got sort of grumpy … which sort of makes me laugh a little. At least I made myself laugh. I now have two kids who prefer their father to the point that my feelings get hurt a lot. It sucks, but also, they are just little kids and it is funny. Karma I guess.

RC: You did an earlier version of Passport in minicomics form, but it was very different from the final version. The sole issue took place when you were five years old and living in Greece. A lot of the same themes were there: a desire for knowledge and control over your environment, as well as a burgeoning sense of patriotism that was inexplicably punished. Kids already have a keenly-defined sense of “fairness”. As a child, how maddening was it to be kept in the dark for what seemed to be entirely arbitrary reasons?

SG: Yes. The original Passport was meant to be the first chapter out of five, but my agent rightfully pointed out that this was not really a book with a shelf to live on and she played a huge role in reshaping Passport to focus on my high school years. But, yes, I hated being left out as a kid. Whether your parents’ work is secret or not, I think all kids must feel this: that the grown-ups have the secrets to the universe [and] are holding out on them. I wanted to know everything about everything. I still do.

RC: I was surprised that the CIA angle that was mentioned so prominently in the book’s promo was played down in the book. However, it made for a more nuanced story, especially once you concluded that your parents were spies. Would you have made that aspect of their lives more prominent if you had the freedom to do so?

SG: I’m not sure I would have because it still makes me nervous to talk about it, despite essentially having written a 300 page comic about it. “The secret” was practically a lifestyle in and of itself and I have loved that lifestyle. Also, I tread very carefully speaking for other people. There is a lot I did not, cannot, know or speak to. On the other hand, I was very constricted on what I could say by the agency’s review board, and I cared about getting this story out there enough to play ball with the powers that be. So a lot of things I was personally comfortable with had to be cut out. I have a lot of respect for the work my parents did and had no intention of writing a treatise on any government entity. I can only speak to my experiences, and I have tried my best to speak clearly.

RC: Passport’s main theme is questioning what it means to be in a family and one’s duty toward that unit, a relentless sense of alienation, but, above all else, it’s about the deliberate slipperiness of identity and truth. In your mind as a teen, how much did you justify creating this alternative identity because of your parents’ own lack of forthrightness?

SG: I think it lent me a lot of justification, both consciously and unconsciously. I felt no obligation towards them when it came to pursuing my own extracurricular activities. All teenagers have a need to differentiate, but I was a bit elaborate about mine. I was very comfortable with playing a game where I pretended to be an obedient grade-getting kid who was a responsive member of a family unit while knowing that we all had our own secret lives. It was freeing to know I owed them no more transparency than they owed me. After all, they taught me how to do it in the first place.

RC: You depict your mother as religious and moralistic. Did your understanding of her false identity disrupt your interest in religion and spur your rebellion?

SG: Not really. My adolescent rebellion did not follow that prototypical rejection of religion and I think that is for complicated reasons. Perhaps because it was such a needed constant in my life. In every country I lived in I could count on finding two things: McDonald’s and the Catholic Church. I was a very religious child and have turned into a somewhat religious adult. I may have resented my parents keeping me in the dark about all sorts of things, but I never saw them as hypocrites, religious or otherwise. Also, and this is the trouble with memoir, I had to choose which sides of my mother to emphasize. I hope I showed her as a complex and complete person, but there were things about our relationship when I was a teenager that did not serve the story as a whole and so are missing from this narrative. My mother is fun and brave and sexy and weird and, in turn, appreciated those things in her children. I think she really enjoyed watching me enjoy myself, but she also had an intense desire to protect and preserve me. Portraying this mix of pride, projection, and protectiveness was very difficult, and, when writing Passport, I relied on the aspects of our relationship which created the most tension.

RC: At the same time, as an adult and mother now, how sympathetic are you now to how difficult a position she was in?

SG: Very, but I always have felt for my mother. I think it is intensely difficult for mothers to separate from their kids and I was weirdly aware of this as a teenager. It’s not that I didn’t understand where she was coming from, I just couldn’t agree. I valued my own adventure too highly. Though it’s true as I look at my own three-year-old and imagine her 12 years hence jumping into cars with strangers after a half a dozen tequila shots I shudder. I lost her at the park last weekend. I just looked up and she was gone. In the 5 minutes I ran around, terrified, searching for her I completely (though temporarily) reversed my position on micro-chipping children. Ask me how I feel about locking kids in towers when she hits puberty.

RC: This is a difficult question, but as an adult, do you think it was fair of your parents to raise a family in such conditions?

SG: I know other people who were raised in comparable circumstances and their experiences varied, but I feel my parents gave me a profound and lifelong gift: a sense of the world, a decentralized sense of culture, perspective, the ability to adapt, the ability to exist in challenging circumstances, the ability to talk to anyone, and to problem solve in complex environments. I had done things, seen things, and tasted things by the time I was sixteen that would have taken me a lifetime of travel as an adult to experience. So it wasn’t fair, but only in the sense that I have been beyond privileged to be given that.

RC: I know your family has been supportive of the book, but what specific reactions have your parents and older siblings had?

SG: My sister, who reads and gives notes on everything I write, has read the very developed early drafts, but no one in my family has actually read the finished book yet. And I’m not going to lie, I’m mildly terrified. Writing about the people you love the most for an audience of strangers is a sticky business.

RC: Did your mom really consider comics to be trash? Did she like anything that you read?

SG: Pretty much. I mean, she just on a fundamental level did not get it. It’s not like I was drawing Garfield or funny comics which I think she would have understood better. At one point I made it my mission to convince my mother that what I was doing was not garbage, that comics were not silly, and I succeeded when I gave her my copies of Art Spiegelman’s Maus. After she read it she was like “oh, I get it, you want to write something like Maus.” I hope she realizes I will never write Maus per se, but it turned her thinking around. She is very enthusiastic these days.

RC: I think the adjective that describes Passport best is “unflinching”. While you are harshly critical of your parents and your sister, you don’t paint yourself as any kind of ideal hero either. What are you hoping that teen readers of the book will get out of this?

SG: That we contain multitudes, that our desperate desire to sort and define ourselves is a messy, nuanced, lifelong journey.

RC: How did your publisher and editor guide you in making the book? Were there things they wanted you to emphasize?

SG: My editor, the amazing Susan Rich, has been the most supportive and insightful person I could have hoped to have been involved in the writing of this book. She has made the transition from self-publishing to working with a formal editor painless and lovely. She was also crucial in preserving the heart of the story as I cut out specific details which would betray the particulars of my parents’ work according to the Publication Review Board of the CIA. She saw it as a fun challenge which was an invaluable point of view for someone who was hysterically sobbing in front of what looked, at first, like a butchered manuscript.

RC: Did you consult other rite-of-passage memoirs or fiction, either in book or comics form? Tonally, the book reminds me a little of the Mariko and Jillian Tamaki collaborations.

SG: Yes. Once I realized I was, in fact, writing a YA book, I gave myself a crash course in the best YA graphic novels out there: Jillian and Mariko Tamaki’s This One Summer and Skim, Tillie Walden’s Spinning, Vera Brosgol’s Be Prepared etc. The Cousins Tamaki are just the be all end all for comics of adolescence in my opinion. Their books are perfect machines, and so if I managed to absorb even just a little of how they do that I am thrilled. Otherwise, some of my favorite comics were already memoirs (Persepolis, Fun Home, Arab of the Future) and have probably influenced me more than I can know.

RC: Now that you’ve told this story, after a career where your experiences clearly informed your fiction as well, what kind of stories do you think you might want to tell?

SG: For now I am not going to write more memoir, but I’m still interested in young women and the experience of being a girl navigating the world. My guiding principle is to write the stories I would have loved to discover back when I was a teenager reading comics. I am amazed by the current availability of excellent books which transcend the typical genre restrictions we associate with comics. It is continually exciting to me and it is something I want to be a part of.

SOLRAD is made possible by the generous donations of readers like you. Support our Patreon campaign, or make a tax-deductible donation to our publisher, Fieldmouse Press, today.

Leave a Reply